Drain Gang

|Cassidy George

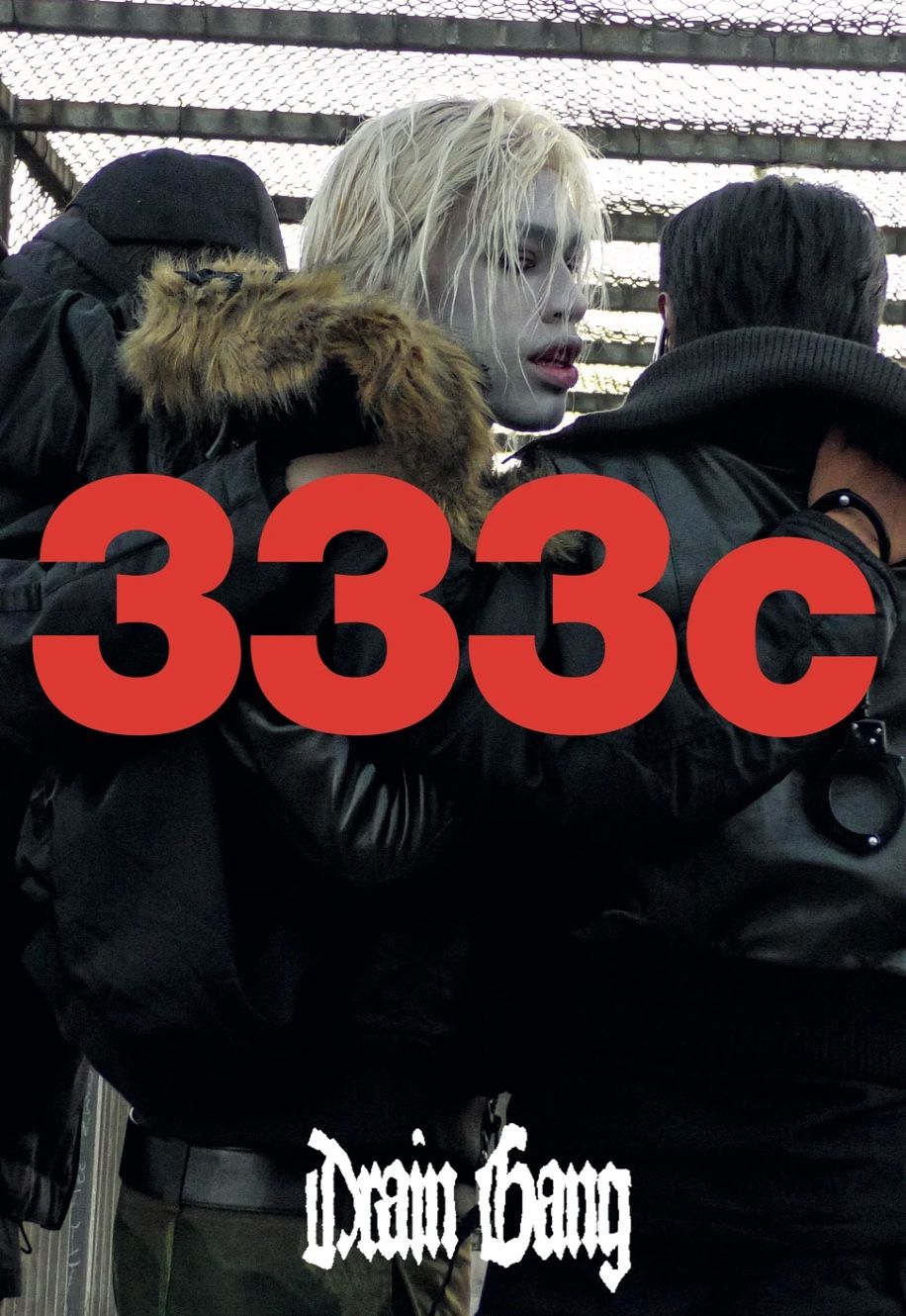

Originally published in 032c #42, the Drain Gang Dossier investigates the mythology surrounding the music collective Drain Gang, consisting of BLADEE, ECCO2K, THAIBOY DIGITAL, and WHITEARMOR.

The members of the avant-garde boy band DRAIN GANG are worshipped like deities by their fans and are regarded as emblems of what Gen Z values in its stars: vulnerability, openness about mental health, and slightly unpolished personas that feel unfiltered by the “machine” of the industry. In a narrative odyssey, Cassidy George unpacks the elaborate myths, polarized politics, and deeper truths that have flourished during their decade-long career.

Drain Gang poster available HERE

Hexed

On the night of the annual Harvest Moon, I was summoned to an unnamed address in an industrial neighborhood at the outskirts of Stockholm to speak with the members of the Swedish music collective Drain Gang. After traversing a desolate, winding road, I arrived at the top of a hill. There I found nothing but an ominous old water tower with lancet windows, surrounded by oversized rocks and plants brimming with wild red berries. The rickety door was locked, and none of the musicians could be found, so I reclined against a rock overlooking the city to soak up the last of the sun’s rays.

Half an hour later, distant murmurs and footsteps became audible, and Ecco2K suddenly approached me from behind. He wore an oversized, furry black hat and a T-shirt ripped into a tube top, which bore the words “DRAMA POWER FAME GREED WASTE MONEY” in large white letters. He apologized for being late and led me through the tall grass, back to the tower. His politeness clashed with the greasy black makeup that was smeared around his eyes, a look that reminded me of Marilyn Manson’s. The others—Bladee, Thaiboy Digital, and Whitearmor—were congregating near the entrance.

"Where are we?” I asked, as Whitearmor fiddled with keys and unlocked the door. As he entered, Ecco2K turned and said, “It’s called the Witchtower.” After we ascended a spiral staircase, Whitearmor and Thaiboy broke off early to enter a cluttered room on the second floor of the tower. Although I caught only a glimpse, it had the uncanny and disturbing feel of a #liminalspace, internet terminology used for disquieting images of transitional areas that cause feelings of apprehension. Bladee and Ecco2K then escorted me up a second flight of stairs, far steeper than the last, which led to a room that the structure's owner had designated for worship. This space, high atop the Witchtower, was full of mystical totems: beady-eyed figurines, dirty Beanie Babies, dream catchers, altars, bells, old books, and an array of different animal bones. The painted image of a goddess, surrounded by what I assumed were ancient runes, adorned the wall.

As I took in my surroundings, Bladee noticed me staring at a handwritten sign hanging above an urn filled with dried rose petals. “It says, ‘Take one and give it to the wind,’” he told me, translating the sign written in his native Swedish. His Scandinavian accent, which is audible on all his tracks, was even heavier than expected. Although online he projects an edge lord persona, in person he radiated an effusive kindness. When I asked about the space’s significance to Drain Gang, Ecco2K answered simply, "We record music here sometimes.”

Drain Your Life

Drain Gang has spent the last decade building a sonic, aesthetic, and material universe complete with its own mythology and lore. Spawning a system of belief that comes with a singular look, sound, and language, the band has bewitched designer Marc Jacobs and has been heralded by pop producers such as Charli XCX and A. G. Cook. Drain Gang helped birth a new strain of meme humor and a TikTok aesthetic called Draincore, which fuses black metal fonts, sparkles, Y2K media, clip art, and obscure lights, plus noisy and trashy visuals. Around 2017, Drain Gang was also credited with inspiring a new wave of experimental, DIY pop music known as digicore and glitchcore—all of which is to say that Drain Gang has cultivated a sphere of influence that now ranks it among the most impactful in youth and underground culture.

Yet the group’s sound horrifies as often as it delights, and its artistic merits remain the subject of fierce debate. In a now infamous YouTube video, Anthony Fantano gave Bladee’s 2018 album Red Light a scathing rating of 1 out of 10, stating:

I’ve really only heard a few projects–a few artists, who are at this visibility level, who are so beyond the help that Auto-Tune can provide .... I guess this album does have a certain awkward-European-who-sits-around-all-day-getting-high-with-his-friends-and-consuming-American-media-through-the-internet appeal to it .... I will commend Bladee on one thing with this record, though: this album, and his sound in general, would be nearly impossible to parody .... There’s no way to tease a funny moment out of it by making a worse-sounding version.

This review echoes many responses to Drain Gang’s music, and not just by the band’s critics. Its Auto-Tune–heavy and high-tech music often sounds like cacophony created by a suicidal robot. Even self-proclaimed fans have admitted to loathing certain tracks upon first listen. Notoriously difficult to describe, the group’s music has earned a laundry list of insufficient and obscure genre categorizations that are humorous in their failure to capture something so amorphous and otherworldly. Even Ecco2K has described his music as being akin to “throwing a car battery into a washing machine.”

Although each artist in the group has a distinct sound, and each member’s respective albums are stages in an ongoing metamorphosis, their collective discography shares certain qualities: hyper-artificial instrumentation influenced by video game culture and trap; atmospheric reverb that simulates a sensation of depth; vocals smothered in Auto-Tune, and often delivered in falsetto, mumbles, whispers, or shrieks; and lyrics that center on the suffering and elation of what it means to be alive and online in the modern world.

The group’s signature catchphrase is “Take a knife and drain your life,” which fans have interpreted both as a nihilist glorification of self-harm and as a rallying cry to embrace the negative feels that plague you. “Drain can mean anything you want it to,” one Reddit user wrote on the group’s fan page in 2017. “When you come down off drugs you feel drained. Love can drain you. Cutting your wrist can drain you.” Bladee, the self-proclaimed “Drain CEO” and de facto frontman for the group, has been quick to clarify that “Drain [is] neither good nor bad. "To him, it represents a process of loss that can either be depleting (draining your energy) or healing (draining your life of negativity).

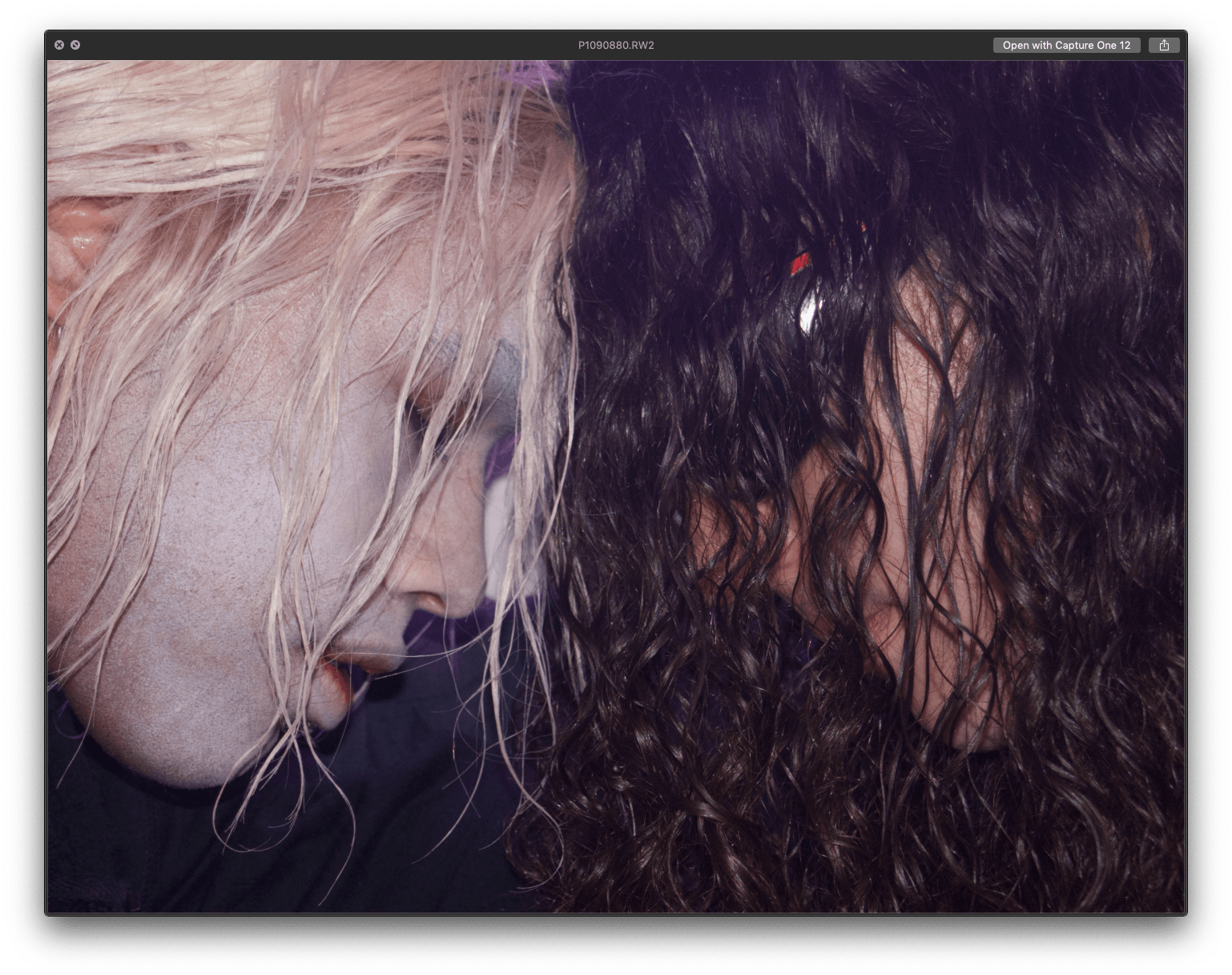

Bladee—whose hair color, texture, and length evoke Western depictions of Jesus—has increasingly assumed the role of a musical messiah. Bladee and Ecco2K’s critically acclaimed album Crest (2022), which was recorded in a studio not far from where Ingmar Bergman shot The Seventh Seal, is better described as a collection of hymns than as an art-pop album. In one of their most infectious tracks, “Amygdala,” Ecco2K and Bladee chant that Valhalla, a heaven-like place in Norse mythology, is calling to them. Bladee, who is also a painter, also channels divinity into his visual art. He cites artist/mystic Hilma af Klint as a central inspiration. Despite this higher calling, the battle between darkness and light, heaven and hell, God and the Devil, grinds on. Bladee’s new album, Spiderr (2022), also features tracks with such titles as “It’s OK to Not Be OK” and “I Am Slowly but Surely Losing Hope.”

In the Witchtower, Part 1

CASSIDY GEORGE: The occult seems to be a major source of inspiration.

ECCO2K: An existential and spiritual component has been present since the beginning, but that perspective is really taking off in the newer work. We believe you can create your own spiritual relationship, and you don’t necessarily have to follow any school of thought or religion or philosophy. You can create your own language and belief systems and makeup your own form of expression. [That] doesn’t make it any less valid. At the end of the day, it’s all just something someone said. Nobody really knows more than anybody else about these things. This idea gives you a lot of freedom, because you don’t have to take any of these perspectives or ideas too seriously. Whatever makes sense to you, you can make your own.

CG: The album Crest felt deeply spiritual.

ECCO2K: In the more recent work, the lyricism is less about me and more about everything else, but still understood through my own experience. Is the goal to get beyond the self?

BLADEE: You get tired of hearing yourself. Even if I’m not talking from my own perspective, or am talking about something that never happened, those feelings are still real. The lyrics are like painting a picture. You want to make it look nice—you want to decorate it. There’s always a core idea that’s based in truth, but it’s more about the feeling that it gives. I think you can always hear when something is true, like in its essence.

ECCO2K: Just because it’s made up doesn’t mean it’s not sincere or authentic.

Noblest Survive

The influence of the Witchtower on Drain Gang’s discography can be heard on tracks written long before the group even had access to it. Mystical lyrics about black magicians, holy swords, evil spirits, and magic stones appear on Bladee’s first album, Gluee (2014). On the track “Everlasting Flames” on that album, Thaiboy chants like a Gregorian monk and raps such lines as “Holy power / Keep me glowing when I’m in the dark.” Drain Gang’s holy mission has only become more pronounced over time. In recent years, Bladee has been vocal about his commitment to positive messaging. In a 2019 interview with The Fader, Bladee said, “Now I feel a little more responsible, because there’s a lot of young people listening to my music, and I don’t want to make it sound cool to be depressed or to dwell on these feelings. I put the worst things that were in my mind in my music, but I know now that I don’t have to do that. I’m trying to change my approach a little bit .... I want to be more positive. You listen to sad music to get out those feelings, but you mustn’t stay in the sadness and get even sadder.”

This attitude feels like a far cry from the overarching themes of Drain Gang’s dark ages, when their music illuminated (and, some might argue, romanticized) cycles of addiction and centered on such topics as interpersonal detachment and an inability to feel love. On the track “Bleach” from GTBSG (2013), Ecco2K sings, “I can bleach the darkness out of your mind / White powder, white pills, leave your body behind.” Bladee’s 2016 record Eversince, which many fans consider to be his masterpiece, sounds like fragile masculinity in the throes of a millennial crisis. With songs, including “Wrist Cry,” that are candidly about self-harm, choruses that bellow “I love to play the victim,” and such lyrics as “Don’t know how to show love / Please don’t get your hopes up / You might get your soul crushed / Closed up like a rosebud,” it is not exactly shocking that their ultra-online sound earned them white male acolytes who identify as involuntary celibates—incels—or as members of the alt-right.

Who Goes There?

Who holds her?

It's not me, I'm a loner

It's bad, it's bad

You don't know what I am

I'm a sick man

And this world feels so distant

But today I'm feelin' so indifferent

By any means I'll be low-key

I'm gonna need a reason to be seen

All the prayer is for nothing

No touching, I find it disgusting

— from Eversince (2016)

Incel No More

In the deepest trenches of internet culture, Drain Gang’s gospel spreads among fans in the bottomless threads of 4chan and Reddit, as well as in the late-night chat rooms of Discord. Here, their outsider status and ballads of alienation have long resonated with those who subscribe to alt-right ideologies. Particularly around the time of Donald Trump’s election, trolls in MAGA hats staked their claim over Drain Gang’s music on digital forums and have made a permanent imprint on the group’s perception—to the great dismay of the artists, who do not subscribe to right-wing or white supremacist ideologies. Fan-generated memes circulating on these forums overemphasized the link between Drain Gang and their extremist fan base, and shaped a concrete stereotype of what a Drainer is: a “neckbeard” or “doomer” with bad posture, bad hygiene, bad mental health, and a bad drug habit. Among the most memed tropes are the catch phrase “The music kind of sucks, but you get used to it” and the “aux cord moment,” a hypothetical situation in which a fan hijacks the aux cord to play Drain Gang’s music for a broader audience at a party or on a date. The punch line is always about the severe social consequences that ensue, implying that “outing” yourself as a Drainer is akin to revealing yourself to be an outcast or monster.

But as Bladee and Ecco2K have increasingly incorporated more queer themes into their work (Ecco2K presents as female in the music video for “Amygdala”), the visibility of their LGBTQ+ listenership has increased online. Their queer, trans, and nonbinary fans now use the same forums as incels to discuss the ways that Drain Gang has helped them to identify gender dysphoria and to embrace their own identities. Drain Gang’s ability to articulate a strain of suffering that is specific to the internet age has bred a fandom encompassing the two most extreme poles of the contemporary political spectrum. Members of both have found safe spaces in the group’s music. The intense arguments that frequently erupt within their digital fan spaces are a microcosm of the broader culture wars. On social media, the diversity of their listenership continues to be obscured by the potency of the Drainer stereotype. On TikTok, Twitter, YouTube, Reddit, and Instagram, Drain Gang concertgoers of all political leanings are asked how many virgins they think are present and how bad the venue will smell.

“Sometimes you don’t have to think about what you’re doing. Sometimes it just happens. But sometimes you have to make an effort.”

In the Rift

The week before spending an evening in the Witchtower, I attended a one-day festival called Rift. The event, which was organized by Drain Gang’s label Year0001, occurred in a massive, repurposed warehouse in Slakthusområdet—Stockholm’s historical meatpacking district. It was a homecoming for the group, who were performing in Stockholm as Drain Gang for the first time. Many friends and family members attended, including Bladee’s grandparents, and the heartwarming energy of a reunion was in the air.

As I entered the concert space, the French ambient-pop musician Oklou was playing “Lurk,” a reworked version of Evanescence’s song “Going Under.” Judging by the prevalence of early-2000s oversized black cargo pants and bejeweled, gothic, Christian Audigier–inspired looks, it could have very well been an Evanescence concert in some speculative past. There were timeless subcultural tropes, too: vibrant hair dye; facial piercings; and oversized, black graphic T-shirts. But the unique accents of the internet age were everywhere: the black-and-white striped undershirts worn by TikTok’s E-boys and E-girls, biker and fishnet gloves, and Euphoria-inspired makeup bespeckled with graphic hearts and stars. Fashion from both ends of the rave wear spectrum (industrial and PLUR) manifested in fuzzy boots and excessive metal hardware. The subjects of Drain Gang’s own fascination—anime, video games, and Harajuku style—made their own sartorial impact. I counted enough animal-eared hats to qualify Rift as a small-scale furry convention. The most memorable look of the night belonged to a Drainer who locked a pair of metal handcuffs around the two buns perched atop her head. When she smiled, the black paint on her two front teeth created the illusion of a massive gap.

The crowd was noticeably more male than female, but many in attendance presented as nonbinary, echoing Ecco2K and Bladee’s increasingly androgynous presentation. When queuing at the bar, the teenage boy standing in front of me suddenly turned around and said, “Will you take my BeReal?” As he thrust his phone toward me, I turned to the crowd and saw a sea of phones and poses, as seemingly every third person stopped in their tracks to use the new, Gen Z–targeted social media app once it was “time to BeReal!” Given that the app is still largely unheard of among those born before 1995, it was a good indication of the age demographic. As Drain Gang toured the world, Drainers themselves became a social media spectacle. Clusters of viral videos emerged after every performance, the most notable ones featuring interviews with Drainers lining up to enter shows. In one popular YouTube video, a teenage boy in Brooklyn is asked about how he got into Drain Gang. “My Dad left me, so I had to find a way to cope,” he explains. When asked why his father abandoned him, the young man replies, “Probably because he thought I was gay,” before nervously adding, “I’m not, though!” In a similar video recorded in the queue for a Drain Gang show in Los Angeles, another Drainer recounts his near fatal overdose and credits his survival to the fact that he was wearing Bladee merch at the time. After this harrowing tale, he pulls out a Ziplock bag containing six ounces of shrooms and shares his plan to consume them all that evening. When another fan asks him if going to a Drain Gang show is a red flag, he replies, “Drain culture is just embracing the red flag.”

Often more amusing than the videos themselves are the comments sections. Many express such sentiments as, “I’m a very normal, normal person. I like the [Drain Gang] boys because if [sic] their unique style, vision, sound, and mysterious personality. I don’t think too hard into it past that. I don’t tie in spirituality or sexuality at all. That being said, I’m embarrassed to be associated with this fan base. Is there any ‘normal’ Bladee fans out here?”

r/sadboys

As teenagers, the members of Drain Gang were introduced to the rising internet star Yung Lean—with whom they would soon share a label, Year0001, and a manager, Emilio Fagone. Yung Lean and the other members of his musical collective, Sad Boys Entertainment, have collaborated frequently with the members of Drain Gang. The two groups are so close that they share some of the same digital fan spaces—including the r/sadboys Reddit forum. With almost 110,000 members, r/sadboys ranks among the platform’s top one percent, according to size. Although better known online by his Reddit username, Mitgas, 22-year-old Russian-born and Finland-based Dmitry joined the r/sadboys community in 2016. Joining originally as a fan of Yung Lean, he would go on to become a moderator of the Sadboys subreddit as well as the Sadboys and Year0001 Discord servers.

CG: What are your responsibilities as a moderator?

Mitgas: It’s different on Discord and Reddit. On Reddit, I’m moderating the quality of what goes up and making sure [users] are keeping with Reddit’s own terms of service, as well as the rules that are unique to r/sadboys, so that I can keep it a fresh and accessible place for everyone. Discord is an active chatroom, so it’s more about constantly monitoring what’s going on, remembering certain people, and really learning from that. It’s about interaction.

CG: Have you noticed the culture of the fandom evolving over time?

Mitgas: One hundred percent. I think it was a bit more—I don’t want to use the word toxic, but it was a crazier place back in the day. Especially around [the time] I joined, in 2016. That was when everything sounded darker, and the artists were more secretive. At some point, there was a big culture switch that I think is reflected in the music. As it got happier and the artists became more open, the fans changed as well. You don’t see people making fun of each other for not having a specific leaked song, or people being mad at each other for not knowing what Yung Lean is wearing in a specific picture. That [behavior] used to be such a big thing in the community, knowing and archiving everything. Now people are more accepting of one another. I’ve also noticed that the joking culture has grown. “The music kind of sucks but you get used to it” was always around, but now the slightly ironic thing is really prevalent.

A Year0001 Interlude

CG: I was surprised to learn that Drain Gang didn’t have a big following in Sweden until recently. As their manager, did [you find] their growth during the pandemic [surprising]?

EMILIO FAGONE: In all honesty, I was expecting this to happen way earlier than it did. There came a point when I was worried that it wasn’t going to happen at all. I was like, “Why isn’t anyone seeing the same thing as me?” Then I realized, if you’re working at the forefront of culture, you just have to be more patient. To be honest, a lot of it has to do with journalism over the past decade. Publications are dying, and writers haven’t been paid properly—and if they don’t get paid, why should they make an effort to indulge in new scenes and cover them?

CG: Drain Gang has an aversion to the press and rarely grants interviews. Is this[reticence] due to the same disappointment in journalism?

EF: Definitely. In the beginning, the press always wrote [about Drain Gang as a] “Lean-affiliated artist,” but for me, it didn’t make sense, because they were all working together and inspiring each other. Publications made it look like [Drain Gang was] getting carried by him, but I know that even Lean doesn’t look at it that way.

CG: That sounds like a lazy clickbait headline.

EF: That’s what the 2010s were. Clickbait.

CG: Do you feel like they are fighting to get out of his shadow?

EF: Not anymore.

CG: You founded the label Year0001 with Oskar Ekman in 2015 and are credited as discovering Lean in 2011. Is there a direct overlap between Sad Boys and Drainers?

EF: They stem from the same base and exist on some of the same forums. There are a lot of fans out there [who] are mainly into Lean and Sad Boys, but then there’s this younger fanbase that would ... recognize themselves as Drainers [only]. We felt like we needed to start something through the label, so we have a Discord server where all the real, hardcore fans are. It’s only been active for six months, and we already have 15,000 users. Now the r/sadboys Reddit moderators are working on our Discord, which helps.

CG: Mitgas told me you were originally in touch because people were leaking Drain Gang’s music.

EF: There were so many moments where people were constantly trying to hack us or trying to leak the music. People were going in and looking at the code of our website to find out additional information.

CG: That hunger for information feels violent. There have also been several attacks on them and you. Does this have to do with the overlap between Drainers and incels, and Drainers and members of the alt-right community? What do you make of that?

EF: In all honesty, I don’t know what to make of it. It’s a sign of the times and the current political climate. There are so many alt-right political movements coming up in every country, mainly in the West. I think maybe the uniqueness of the sound and them being quite private means that a lot of people can misinterpret it. I feel like it used to be worse. In the past two or three years there’s also been a big change in the fan base. People are speaking out more against that in the community, which I really appreciate. But I'm not going to lie, there are a lot of people who are misbehaving and trying to fuel some type of negativity. I suppose that’s unavoidable when it comes to stardom. All we can do is try and communicate what we feel is okay, which we are constantly doing with the capacities that we have. I definitely don’t want to ignore issues that exist within our community, but there’s only so much time and effort that you can make. I know what my artists stand for, politically and in terms of values. That’s why I’m still baffled that people would even try to—

CG: Co-opt it?

EF: Yeah.

CG: I suppose a lot of that stems from the fact that they are men who have been quite frank about mental health, which was a somewhat rare and transgressive thing to do in the hip-hop space ten years ago. But that same quality has also built the bridge to the Gen Z fandom, even though Drain Gang is not of that generation.

“We believe you can create your own spiritual relationship.”

Calcium

Oh, I’m unraveling, and I’m panicking

Feel like I’m paper-thin, and now I’m tearing

Help me please, give me calcium, I think I’m fracturing

I need bandaging, don’t take me back again

I feel like Marilyn, but I’m not acting again

This might be the end, I think it might be

I’m seeing evil men, am I imagining them?

I think I might be

I feel like I’m flying

And sinking at the same time

Like I’m being pulled from below

And from above

In every direction, at once

— from Ecco2K, E(2019)

If Being Drainy is a Sin, Lord Forgive Me

One telltale sign of a cult is a followership that is instilled with a sense of spiritual supremacy. The “us-versus-them” mentality at the core of this feeling emphasizes that those in the know are elite members who are fundamentally different from—and therefore better than—nonbelievers. As communities become more insular and further detached from mainstream norms, it nurtures a more radical form of devotion.

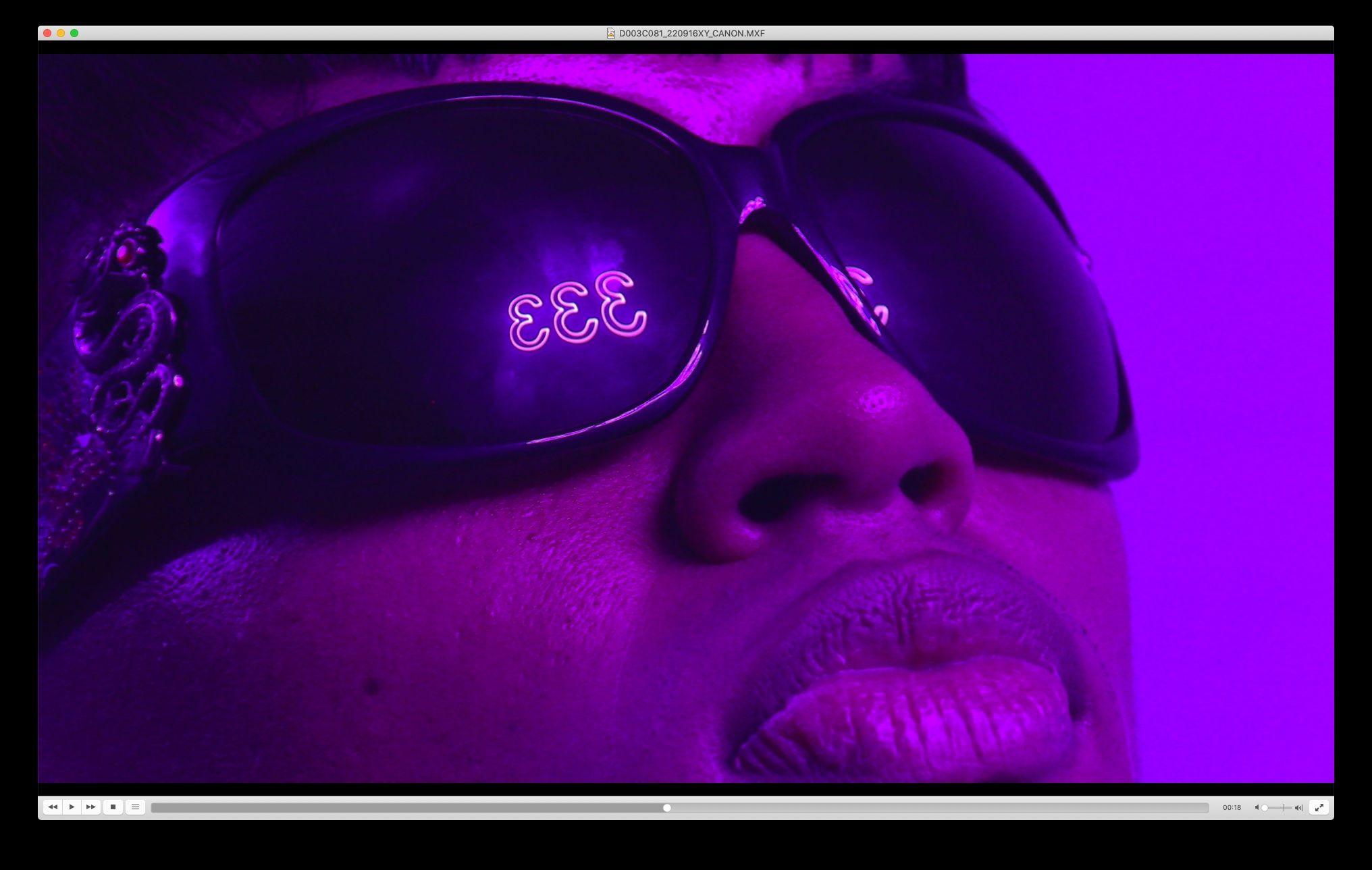

Drain Gang stokes similar sentiments with disorienting and cryptic music videos, posts, and lyrics, which often include incoherent combinations of letters, numbers, and symbols that can be deciphered—if that is possible—only by those who are already believers. Their lyrical world is filled with recurring icons, tropes, and acronyms—such as GTBSG (Gravity Boys Shield Gang), d9 (drain 9ang), and the use of the holy number 3 (including in Bladee’s 2020 album title, 333)—that are as hard to decipher as a QAnon post.

CG: Do you think that part of the obsession with Drain Gang comes from feeling like you are part of a niche community, or among the chosen few who get it?

MITGAS: For sure. I think that’s a natural part of it. You definitely feel special.

CG: Do you think that feeling of being special is in danger of wearing off as their presence increases?

MITGAS: I don’t think that’s a negative thing, but some people do. To me, it just comes down to whether ... the artists continue being who they are. They’ve always been very true to themselves. As long as they continue doing whatever the hell they want, it’s never going to be uncool.

CG: Has their being so unapologetically themselves influenced you?

MITGAS: [It] has had all kinds of impacts on my life—from more arbitrary things, like clothing or the way that I talk and the music I’m into, to more serious stuff, like the way that I go through difficult experiences, or the way I think of social issues. Their views and the way they are have definitely helped me.

CG: You’ve even been influenced by their political views?

MITGAS: Absolutely.

CG: And they’ve become more vocal about those over time, right?

MITGAS: I think it was always there. I remember Whitearmor’s tweet dissing his white alt-right fans in 2017. That helped me a lot. The community used to be more of a platform for people to be open about being a piece of shit. But now it definitely helps, seeing how they talk about certain issues or seeing Yung Lean in the back of his magazine saying, “Don’t be a homophobe.” This music has helped make me a better person.

In the Witchtower, Part 2

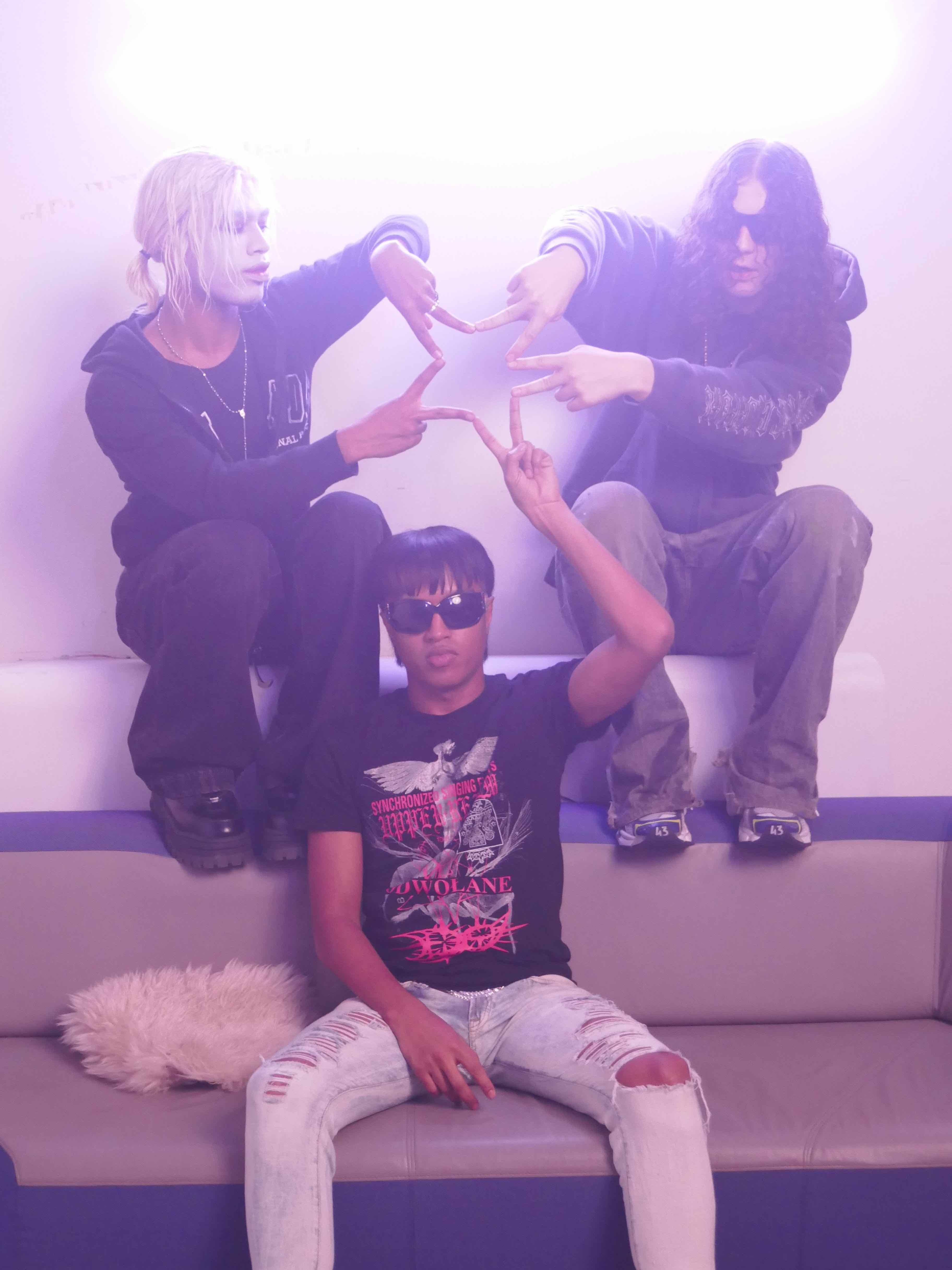

To converse with Ecco2K is to maintain a level of directness and intensity that would make some people uncomfortable. When he looks at you, it feels as though he is piercing through your soul (or at least through your internal organs) and assessing its merit. Bladee, the internet’s archangel, is never the first to answer a question but is always the first to laugh. He carries himself with the lightness of a nymph, and he spent a portion of the interview braiding his hair into various plaits. His goofiness warmed the room, melting the formality of the experience into something more casual. Whitearmor, the group’s sonic mastermind, is Drain Gang’s dark horse. He can say the most with the fewest words. When he did interject, it was often with a sharp-tongued quip. Thaiboy, who has dubbed himself Drain Gang’s “legendary member,” said almost nothing for the duration of the discussion. But the sense of humor he is known for online—bolstered by tweets that say such things as “Imma make sure I b rich af before I die so I can buy a beat off Beethoven in da afterlife”—was present on his graphic T-shirt, which had fake suspenders in the Irish flag’s colors and read, “Let the shenanigans begin.”

CG: This notion of the “aux cord moment” in Drainer culture reminds me of when my parents saw a Jackson Pollock painting for the first time. With no knowledge of the painting’s significance in the canon, they had a visceral, emotional reaction to Lucifer in person –even if [it was] only pure confusion.

WHITEARMOR: Pollock’s outlook was that abstraction would become normal or “pop,” but our music is not abstract at its core like a Pollock painting. These are basically normal pop songs. I think people are just deterred by the way [the music] is delivered. It’s fairly conventional music, but it’s delivered with some of the more characteristic things that we do, which might be distracting.

ECCO2K: When you’re tuned to listen for certain things, you have to retune yourself. Those normal things that you’re listening for are not in the same place in our music, or [they] are often not there at all. If you’re coming at it expecting to hear something you would normally hear in what you like, you have to adjust.

CG: Do you seriously think your music is “pretty conventional?”

ECCO2K: It’s funny, because I don’t agree with Whitearmor at all. I think if we wanted to make normal-sounding music, [that] wouldn’t even be possible. Maybe it’s true that it’s conventional music delivered in a funny way, but it still feels very magical to me. But [our] having different perspectives is what makes it fun. He knows that it’s crazy music, but he also has a drier sense of humor towards the work.

WHITEARMOR: I always thought we were getting into the world of the music we listened to, which was pretty normal rap music. I couldn’t understand why our stuff was not connecting with the people we wanted to work with—which, in the beginning, was someone like Chief Keef. I couldn’t understand why only niche internet artists wanted to work with us. I thought, “This is not like our music.” To me, our music sounded normal. [all laugh]

CG: The music is extremely intimate, but you have succeeded in preventing people from believing that they know the real you. Has your decision to maintain distance left too much room for projection and misunderstanding?

ECCO2K: Yes. Definitely. It happens all the time. That kind of stuff has nothing to do with us. It’s the result of everyone else’s experience. It’s more about them than it is about us.

BLADEE: Although we’ve managed to keep things within our inner circle, we have to accept that we can’t control outside narratives.

ECCO2K: All we want is privacy. Personal stuff is not [anyone else’s] business. People make stuff up and speculate, but the alternative to that is way more uncomfortable. I would rather have people make guesses.

BLADEE: Everyone has their own ideas and sees [things] from their own perspective. As long as it’s not harmful, you can see it as a form of flattery that they care enough to make up theories. When we were smaller, there were even more distorted views. In a way, it feels easier to handle when [Drain Gang is] bigger.

CG: Now that you are visible and influential figures in youth culture, do you ever feel like you got more than you bargained for?

BLADEE: I don’t think about what the fans think. We have always done what we do, and the good thing that comes from that is ... we do it ourselves, and we don’t let other people control what we’re doing. We’re aware that it’s become something quite different now, but I don’t think that affects our creative process.

CG: Does the Drainer stereotype ever frustrate you because it’s far from the truth?

BLADEE: I feel like it doesn’t really have anything to do with us. It’s funny—I feel like our fans are what emo kids used to be when we were growing up. Subgenres creating these distinct groups like punks, ravers, or emos—[that mostly] doesn’t exist anymore, but it exists within our community. People have a distinct look. I think our ideas are elaborated by …

ECCO2K: ... being able to see ourselves from outside and having it reflected back.

Obedient

Can’t you see it?

Bad dog, but for you I’m obedient

Trash Star, cross my heart, that’s the reason

Look up at the stars, they’re retreating

Don’t get lost, don’t live what I’m preaching

Drain Jesus, ice me immediately

Can’t even come home when it’s freezing

925, burn me my medallion

White gate calling me, won’t be long now

I can’t even put those words in my songs now

Big strong compounds, life force get crossed out

Siren ring calling, ambulance sound

Drain Gang track you down like a Bloodhound

I can’t even trust myself when the night comes

Four doors, red or blue, pick the right one

It’s some writing on the wall, it said “Die scum”

I wanna see heads roll, execute past life

Hundred white birds, ninety-nine fall out the sky

Fast life, race against time, it will outrun you

Rains return to the earth, sunlight to the underworld

Maybe in another life we could be lovers

Ever since we met, these thoughts keep getting worse

Iron will, ironed shirt, now I want a Fendi purse

I don’t talk with empty words, what is any of it worth?

Every time I close my eyes, I go to prison

Every now and again, I can feel the distance

Woke up running, I’m still running through the system

Want a new sickness, want to fall victim

Get blacklisted at all the clubs in Seven Sisters

Industry children play with three sixes

Every time I close my eyes, I stop existing

– Excerpted from Bladee and Ecco2k, Redlight (2018)

In Sync

In interviews and on tracks, Bladee has boasted that Drain Gang is “the new One Direction.” When observing all the bulging, heart-shaped eyes in the crowd at Rift, it is impossible to deny the power of the boyband effect, where each member is a heart throb but of a differing tenor. Immobile behind his CDJs at the back of the stage, Whitearmor is the group’s audio overlord. With his sunglasses on and hoodie up, the engineer behind the group’s experimental sound resolutely remains behind the scenes, even when onstage—he is there but seemingly does not care to be. Ecco2K, in contrast, blossoms when performing and singing his music from PXE like a Swedish siren. He raised my hairs on multiple occasions during the show, but particularly when he dropped to his knees and scream-sang “Blue Eyes,” a haunting track that many have read as an expression of what it feels like to be Black in a sea of Scandinavian homogeneity.

Thaiboy Digital is often the gateway drug for Drainerdom, luring in fans of more traditional rap. Thaiboy, who moved to Sweden as a child and was forced to return to Thailand in 2015, is both a Romeo and gangster for the group. He draws inspiration from Soulja Boy and 50 Cent, with lyrics that often cycle between “getting bands” and falling in love. On stage, his droning rap evolves into something more high-energy and bouncy, letting him channel some of the hyped-up Atlanta energy simmering under the brim of Drain Gang’s discography. The crowd erupted when he performed his hit “I’m Fresh,” which has the same borderline genius/borderline annoying style of repetition that catalyzed Migos’ breakthrough with “Versace.” Judging by streams, followers, releases, and the engagement of his fanbase, Bladee is the Harry Styles of the group. An androgynous oddball, Bladee is subject to so much drooling fascination, thanks not only to his looks but also to his generosity. He has released six albums since 2020 and gives obsessives the most material to work with. Drain Gang’s stage at Rift was sparsely yet effectively decorated with structures that looked like ancient tree stumps from a haunted fairytale.

At the beginning of the performance, a thick cloud of fog loomed over the stage and helped to obscure the artists, who are often exclusively lit from the back on tour. Drain Gang does not perform as people but as silhouettes, which highlights the fact that they have been in the guise of avatars while cultivating their following. Projected on the screen behind them was a feed of live video, shot only from the back, which was layered with distorted, glitchy, and pixelated filters that offered accelerationist and impressionist ambiance. Ecco2K, Bladee, and Thaiboy Digital rotated in and out of the spotlight, frequently embracing each other around the waist between tracks and during applause. These displays of tenderness were not unique to their homecoming—most videos of Drain Gang performances circulating online show the three friends as glowing yet shadowy figures, arm in arm.

In the Witchtower, Part 3

CG: Thaiboy, you’re the farthest away, geographically speaking. Do you ever feel like the odd man out?

THAIBOY: Not really. Once I enter this dimension, through songs or videos, the distance isn’t real anymore. When we see each other, it feels like yesterday.

CG: How was the show in Poland, earlier this week? It looked nuts.

ECCO2K: It was intense. We had to move the show, and people were really upset. We got a lot of death threats.

BLADEE: We canceled it twice.

CG: And so fans said, “We’re going to kill you?”

ECCO2K: Either that, or “Kill yourself.” I don’t know if anyone has ever come for us that much. It ended up being really good, though.

CG: Knives were not thrown at you?

ECCO2K: No, but we were ready for that.

BLADEE: On the second night they oversold the venue, so there were too many people, and it was really hectic. People were being pushed, and there were so many security guards yelling.

ECCO2K: People were climbing over gates. When we left the venue, there was a crowd of people running after our car. It stopped at a red light, and they caught up with us and surrounded the car, then laid [themselves] on it and took pictures through the windows.

BLADEE: The America tour was the first time we experienced how big our music is right now. This fame thing, it’s absurd to me.

ECCO2K: Usually, you think it’s going well because you’re seeing numbers and statistics. You don’t ever really see what that means until you go somewhere, perform, and see all the people who are listening to the music. All you have to do is look someone in the eye and say hello. You can tell it’s a really big deal to them.

BLADEE: For me, playing a show is completely different from the music. I don’t necessarily associate it with anything else we do.

ECCO2K: I really love performing. It’s one of the only contexts where I am completely free of self-awareness. For me, the shortest path from my inner self to the outer world is expressing myself through my body and my voice. When we’re performing, I’m not aware of myself, which for me happens pretty rarely. It’s such a direct way to communicate, and that’s something I feel lucky to have. In all the other mediums that I work in, the process is way more complex. On stage, it’s like I’m not even really there. It feels more like I am observing from the outside. It’s weird, because I would not be comfortable singing to somebody alone in a room or in front of five people. But if it’s 3,000 people, it’s fine.

CG: I take it you aren’t a karaoke person?

ECCO2K: I’ve gotten into it a few times. They know how to do it in Asia. I’ve enjoyed it there. I sing “Like a G6” every time.

CG: The other day, I came across a cheesy self-help book called Effortless, which reminded me of you. The thesis is that, even though we think we need to painstakingly agonize over the things we create, our best work is effortless. Everything Drain Gang does looks effortless. But does it feel effortless?

ECCO2K: I don’t think any of us has a single philosophy when it comes to how to make things. Every time it’s different. Sometimes you don’t have to think about what you’re doing. Sometimes it just happens. But sometimes you have to make an effort. We think it’s important, of course, that it always feels sincere.

BLADEE: I can’t do anything when I have to. I can’t work in any other way. So, in that way, it’s effortless. If I feel pressured to do something, then I won’t do it!

CG: Ecco, in your last interview for 032c, you said, “I don’t want anything.” Do you all feel that way?

THAIBOY: I just want to make more hits.

WHITEARMOR: Yeah, more bangers! [all laugh]

WHITEARMOR: The answer to that question is different for all of us.

BLADEE: We always arrive at something interesting through the music that we didn’t expect. We never set out to play huge shows or to have a cult fanbase, but there’s always something fun and unexpected happening.

ECCO2K: We just want to make something that you haven’t seen or heard before. Otherwise, there’s no point in doing it at all.

CG: Do you edit each other? Do you ever say, “Dude, that’s garbage!”

WHITEARMOR: Either it’s good or it’s not. That’s about as far as we go in analyzing. You either want to hear the track one more time or you don’t.

ECCO2K: We trust each other. I feel like they’re all the best at what they’re doing.

BLADEE: We push each other, if anything. What’s the best thing you can make that you haven’t been able to achieve? That’s always the goal.

ECCO2K: Our work isn’t defined by any one particular style or aesthetic. The work takes many forms. The point is that we’ve never thought, “This doesn’t fit in” or “That doesn’t make sense.” What we like – that’s what it is. I think it’s maybe more the attitude or the method behind it that’s consistent.

CG: How would you describe the Drain Gang attitude?

ECCO2K: I think it’s mostly influenced by the fact that we are all completely self-taught. We always had to work with what we had, and that’s how we cut our teeth. The process hasn’t changed that much. Even though the expressions themselves can be quite varied, the fact that we still make all our stuff and keep it very DIY is the common thread. You don’t have to go to fucking art school or anything like that, you can just do it. You don’t need anything other than yourself.

CG: The one question I’ve been asking myself over the past eight years is: who broke everyone’s heart? [all laugh]

WHITEARMOR: It’s been eight years. That’s a lot of people to out.

BLADEE: We’re just emotional!

THAIBOY: Yeah, it’s just a general feeling.

CG: So, the secret ingredient is suffering?

WHITEARMOR: Lately, the music is way less like that.

ECCO2K: But when there’s no vulnerability, then it’s no fun for anyone. Even if it’s scary or uncomfortable to be vulnerable, it’s impossible to accept love from other people if you can’t yourself be vulnerable. I feel like I’m incapable of holding stuff in. It’s more painful to carry things than it is to be rejected or feel shame.

Search True

In comes I

The shortest straw I draw and fantasize

About another time

And walk forward with pride

I find a reason for the madness

Silent sigh

He sleeps and dreams of life

Wakes up and sees both sides

From the darkness came a light

And the two align

And only truth shines through

The truth finds you

Intentions pure for all

And nothing’s unholy at all

The destination’s close for once

And all the struggles wasn’t lost

And all the patience did pay o"(Yeah)

And all the sinning gets absolved

And everything I thought I was (Yeah)

Becomes like shadows in the dark (Drain Gang)

I wake up from this dream I love

And I see everything, see everything at once

– from Bladee, The Fool (2021)

The 9 Is Up

Over the course of our discussion in the Witchtower, I was struck by how comfortable Drain Gang was with defiance, often responding to interview questions with a point-blank “No” or “Not really.” At one point, Ecco2K responded to a query with: “I don’t know! It’s not our job to intellectualize our own work!” Although it was disarming, I should have been prepared. It’s a byproduct of one of their most characteristic traits – a refusal to be led down any path, either creatively or conceptually, that they did not forge themselves. When the members of Drain Gang are asked about their method of creation, they are quick to deny the use of strategy or even the existence of an organized, orchestrated intention. Bladee does not write ahead of time, opting instead to create lyrics on the spot during recording sessions. Guided almost totally by intuition, Drain Gang’s process is akin to the surrealist method of psychic automatism, described by André Breton in his 1924 manifesto as “the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns.” Much of what they make – the music, high-seizure-warning music videos, and anarchic merch designs – unearths moods, fragments, and atmospheres that appear to be extracted from the subconscious.

The genius of Drain Gang is not necessarily rooted in its output, but rather in its purity. While it is true that Drain Gang has upgraded and embodied the ethos of punk for the streaming era, and provided catharsis for digital malaise by creating a sound that is such a direct extension of it, there is no grand design at play here. Drain Gang, at its core, is a resourceful group of childhood friends who collaborate in an idyllic vacuum of their own design. In sharing their art with the world, they offer glimpses into a mode of being that revolves around an exotic and expiring idea: expression for expression’s sake. But what Drain Gang is matters less than what the group is believed to be. Its members’ transformation into geniuses, saints, and sex symbols says less about the artists than it does about their listeners’ attempts to navigate the dark depths of the digital abyss. Although their music speaks to the zeitgeist, they are incarnations not only of a contemporary phenomenon, but also of an ancient one. The “Drain Story” is about our need to find meaning, even where there is none. It is not about a divine savior but rather a collective belief, one that turns water into wine. When it came time to part ways, I asked how they would spend the rest of their evening. “We’re going to stay and record a bit,” Ecco2K said. They then walked down the hill outside the Witchtower to retrieve their equipment, and I returned to my original lookout point. Staring at the oversized red moon, I pulled out of a pocket my souvenir from the Witchtower. I am not a spiritual person, but I felt the urge to do as instructed. I closed my eyes, held my dried rose petal tight, and then gave it to the wind.

“We just want to make something that you haven’t seen or heard before. Otherwise, there’s no point in doing it all.”

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

- Fashion: Ras Bartram

- Photography: Hendrik Schneider

Related Content

032c Issue #42 “DRAIN GANG” Winter 2022/2023

“I Don’t Want Anything”: An Interview with ECCO2K

Uchronia Without Bounds: London Hardcore

Origin of the Gothic and Sublime: Becoming RICCARDO TISCI

Runway Music: Electro-Indie-It-Girls

LANCEY FOUX: Purple Reign

Dark harps, stage fright, and Ryuichi Sakamoto: Introducing NICO HUZELLA

Runway Music: Musicology for Clothes