DEAR MICHEL MAJERUS (1967–2002)

|MAHFUZ SULTAN

In anticipation of MICHEL MAJERUS’ exhibition Let's Play G3, curated by Cory Arcangel, opening at the Michel Majerus Estate in Berlin on Thursday, April 25, we’re publishing MAHFUZ SULTAN’S posthumous feature on the artist from Issue #43.

Painter and anti-painter; Modernist and antimodernist. Right at the turn of the millennium, the artist Michel Majerus (1967–2002) made paintings, installations, and videos that documented the collision of high art and the first internet era, when the monitor became as ubiquitous as the window. From Kippenberger to Super Mario to Toy Story, from Baselitz to Hackers to Nikes, his images prophesy a time when everything – high, low, banal, and profound – violates the law of genre and (thankfully) nothing seems to know its place anymore. Some 15 years before Instagram reached its apogee and eventual decline, he captured the techno-optimism and anxieties of the Y2K era. And it was all very, very fucking cool.

The first time Michel Majerus was born was on June 9, 1967, in Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg. Let’s picture a more or less bourgeois, Central European setting: the carriage-width streets lined with townhouses of varied and forgettable extraction, a stately town hall and cobblestones, and a river crisscrossed by footbridges. I imagine young Michel as a sullen outsider – precocious, aloof – leaning against a fence, watching a crowd of children chase a ball, or later, as a teenager, playing an Atari 2600 late into the night. I imagine him as a new and alien presence in the living rooms of that time and place (did he sit in a hand-me-down Biedermeier chair while he played Pac-Man?). Perhaps he saw videos of Tony Hawk or Rodney Mullen at the home of a friend from the international school, or maybe he traded a copy of Space Invaders to a tourist for a Bones Brigade shirt at a local arcade.

Now let’s leave Esch-sur-Alzette behind, for good. Majerus certainly did – mention of his upbringing rarely figures in his story. From 1986 to 1992, he studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart, first with the abstract painter K.R.H. Sonderborg, prone to brushstrokes of almost Wagnerian self-importance, and then with Joseph Kosuth, the conceptualist and arch critic of contemporary painting. In 1993, Majerus moved to Berlin, the city that would define him.

HEIKE-KARIN FÖLL, Partner: Michel would always calculate how much money he had left, and how many canvases, colors, and stretchers he could buy. He would eat lentils for weeks – that was the price he was willing to pay to work solely as a painter. At the same time, he was very aware of the price tags on other artists’ paintings. He would consciously decide with whom he would like to work – and how he envisioned his own art.

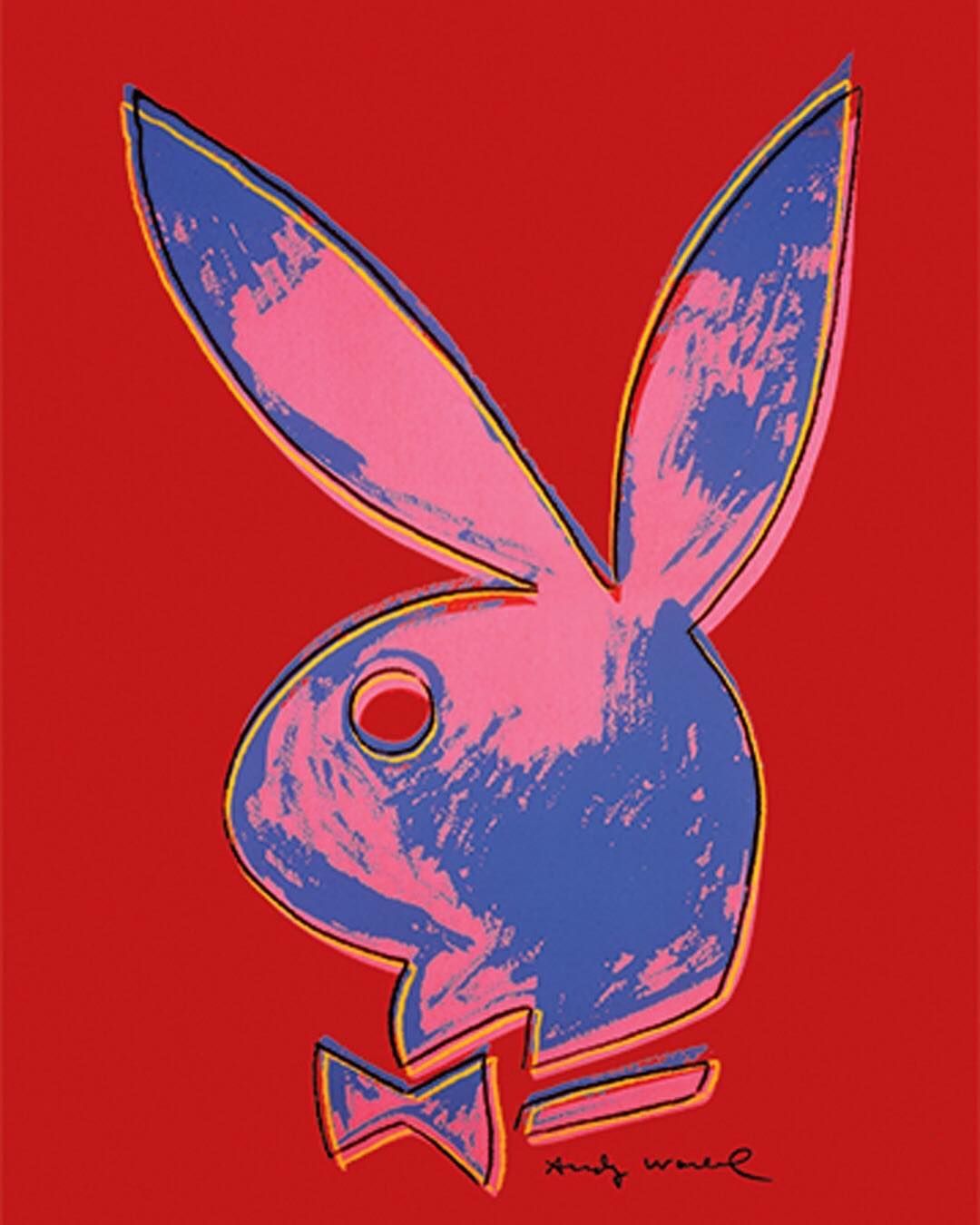

A facile projection of his biography onto his work could read aspects of his time under the tutelage of these two artists into much of the production that followed. He was deeply committed to the history of painting. He lifted his references, with the beautiful inexactitude of Elaine Sturtevant, from such artists as Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sigmar Polke, Frank Stella, Cy Twombly, Martin Kippenberger, and Barnett Newman, among others. His moments of bravura sometimes led to a cut-and-paste gesture from a painting he admired, at other times to a flourish altogether his own. He translated the language of Pop Art into a personal idiom informed by an adolescence spent in the twilight of the Cold War era and an early adulthood in Berlin after the Wall came down: skate logos, video games, techno, nightclubs, sneakers, comic books, advertisements. And yet, for him, Pop Art itself was also just a set of references, just one more strategy deployed with a smirk.

Then again, there was Majerus the conceptualist, the artist who scrawled wry, ironic turns of phrase across his paintings. Like Kosuth, he believed in the materiality of the spoken word. He often made images that were intended to be read aloud. The Brechtian moments of self-reference via the use of text afforded him a certain critical distance from his own production. His paintings were staged almost as “performances,” meta-paintings, littered with visual quotes, stages upon which he thrust the various conflicting formal agendas and visual regimes from the history of painting and image-making, the friction between high art and popular culture.

Most importantly, from the very beginning of his career, his work was very, very cool. This aspect is something that I cannot translate well into writing – the fundamental sexiness of the work; the sense that it was hardwired into the same energy reserves from which everything cool draws.

JORDAN WOLFSON, Artist: Compared to today’s CGI resolutions, these icons now appear crude and rough, as if cut with a butter knife. Michel knew that what looks good today may not look good tomorrow. [His painting of that name from 2000], with its floating circles and matter-of-fact statement, could at once be a moderate political advert as well as the packaging for Western Europe’s favorite birth control. It’s gentle, hostile, sexually numb yet still seductive. It’s Cézanne’s apples. It was completed in under forty-five minutes, which may have been too long! See, that was his point. And so Michel repeats and repeats like a teasing bully, “What looks good today may not look good tomorrow.” The painting works like a spell, cast into viewers’ retinas so that they might see differently for a moment – something ugly is beautiful, something beautiful is boring. But when he picked it, it was ripe – so it’s your fault if you don’t like it. And for this, Michel was the trickster. He wanted to cradle you, punish you, and top it with a playful kiss – but don’t dare take your eyes off him, because he’s the one with the mirror.

In 1996, Majerus radically changed course. He began using off-the-shelf aluminum panels for his paintings. As an early adopter of Photoshop, he often manipulated images on a computer before painting them onto his canvases. He began silkscreening the image files themselves directly onto the panels. These untitled monochromes are his most ubiquitous images, each painted a single luminous color with a small window in the corner into which he screen-printed Super Mario in mid-flight, or Buzz Lightyear and Woody from Toy Story (1995), on a white background. The attitudes of these avatars seemed to distribute themselves across the canvas, charging these monochromes with something contemporary and altogether different from the works by Ellsworth Kelly and Barnett Newman with which they seem nominally in dialogue. The aluminum surfaces gave them a heightened flatness and RGB-like quality – a hyperreal effect. These paintings emit the glow of the digital screen.

For all the variety and inventiveness of his work before 1996, the canvas with its painterly ground felt like an extension of the recent history of painting; a fly 1990s Y2K afterlife for Pop Art and the painters of the 1980s. These canvases were redolent of Polke and Kippenberger. At the risk of sounding reductive, before 1996 his images still seemed to sink into the canvas. They staged the narratives and conflicts of a new reality in the terrain of the past. However, once Majerus set his work on aluminum panels, with their slick, high-tech edges and flat, reflective surfaces, he seemed to anticipate something altogether different – the digital moodboard, the collision of references high and low that are now a fact of everyday life on Instagram, Are.na, and the walls of design studios in an era when Google searching constitutes a formal methodology, and a work of architecture or painting begins with a photoshopped image as often as it does with a sketch.

Nearly a decade after his death, Majerus experienced a second birth – this time reborn as a set of recurring online images of his work that moved in a relay of references, from art history to sneaker culture and advertising, that in combination seemed to recall the surface of his paintings themselves. This vast, enveloping online territory of 1990s nostalgia is one that we know only too well, that we now refer to as “culture”: young Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix on the set of My Own Private Idaho (1991); Mark Borthwick photographs of Stella Tennant cropped from Maison Martin Margiela publications (lots of Margiela, lots of Helmut Lang); Michael Jordan in midflight; the cast of Point Break (1991) in midflight; Jordan’s sneakers in endless contexts; Missy Elliott in fisheye perspective; Nike and Adidas advertisements so saturated in graphics pulled from late 90s Dutch and German rave culture in the futile effort to appear subcultural that one almost suspects Majerus’ installation for Manifesta 2, with its giant sneaker and swirl of zany colors, sits on every single agency moodboard these brands employ; Nirvana, anything Nirvana; Björk; Tron (1982), or Daft Punk channeling Tron, or Kanye West channeling Daft Punk channeling Tron, or some miscellaneous “creative director” channeling all of the above for an album cover of exceptional banality, none of which was set in the time in question, but should have been; Akira (1988), Studio Ghibli productions, Perfect Blue (1997), and Ghost in the Shell (1995) all being mistaken for one another in the comments, because the people who post anything from these films don’t watch anime; Aaliyah fit pics; film stills from Larry Clark’s Kids (1995) and early Supreme nostalgia, virtually indistinguishable from one another; Harmony Korine, Chloë Sevigny, white kids (and a few Black kids for mise-en-scène) sitting on lumpy furniture in downtown apartments or posing as Lafayette Street recedes in the background; Dana Lixenberg photos of Biggie and Tupac for Vibe Magazine; Girl and Chocolate skate-team stills and advertisements; young Winona Ryder in a red T-shirt outside a gas station; Kirsten Dunst and Sofia Coppola on the set of The Virgin Suicides (1999); young Sofia Coppola anywhere, doing almost anything; 1990s logo fever, especially the PlayStation logo; and so on, ad nauseam. To generate this list in full would take several lifetimes. The 90s do not have infinite iteration. It’s just our fixation upon them that seems endless. Instagram is a landscape of Millennial nostalgia, and Majerus’ paintings seem to speak to our time from the past, as if looking back on it.

Artist Takashi Murakami seemingly discovered Majerus only after joining Instagram; he claimed an algorithm introduced the two of them. It’s remarkable that someone who studied painting as assiduously as did Murakami never encountered him earlier – or if he did, then he didn’t notice him enough to remember him. In one near-ubiquitous online image, an untitled Majerus painting with the word “motivation” set in an olive sphere hangs above the head of Frank Ocean’s bed. In another, Majerus’ painting what looks good today may not look good tomorrow (2000) flanks Ocean in a photo of a visit to MoMA. For years, these images seemed to follow me and my friends around the internet. Why? What was it about the unexpected coalescence of Frank Ocean and Michel Majerus in the same images that so moved an internet public that, of course, reveres Ocean as one of our greatest artists, but is hardly (if at all) immersed in the milieu and codes of post–Cold War Central European painting?

Does something about the experience of Majerus’ work on a screen, found in a sea of seemingly unrelated images that share the same database, make it at once salient to a painter and to a general public beyond art world “specialists”? Why do his paintings, filled with dense, often obscure allusions to art history and the contemporary art of his time, have such universal and immediate legibility? How does the slickness of their surfaces, the attitude of their characters, and the irreverence of the text suddenly seem like the coolest thing in the world to an audience that does not even need to register its art historical freight to realize its absolute significance?

HEIKE-KARIN FÖLL, Partner: With every new console or game on the market, Michel’s universe of references seemed to expand, yet everyone could understand his code, as he was copying and pasting from the collective subconscious. Martin Kippenberger’s sense of humor is difficult to understand if you don’t speak German, but Michel’s pictorial language was like an Esperanto of images. Everybody in the world can relate to Super Mario.

To be sure, the bitmapped characters, the pixelated graphics and logos of Ocean’s jewelry brand Homer recall the gaming landscape of the late 1990s and early 2000s that Majerus was saturated in, and the Y2K graphics and energy of the visual cosmos around such brands as Marc Jacobs’ Heaven seem consonant with Majerus’ world, with its deft overlap of 90s alternative music and rave culture. Yet this rhyming hardly constitutes an explanation. Nor should it establish any paternity on Majerus’ part. Rather, he seems to be in dialogue with the work of others today as if he were their contemporary. Majerus was documenting the early years of the visual soup that so many of us were born into.

Born an entire generation before me, Majerus discovered a way to abstract the density of lived experience right at the dawn of the internet, when a screen became the medium through which I apprehended everything. Majerus was born again because his work suddenly became salient, nearly a decade after his passing. It seemed already hardwired into the nature of things around us. It was always already contemporary.

Now, by all accounts, Majerus made paintings very quickly. Christopher Wool once claimed (presumably with mild exaggeration) that Majerus finished some paintings in minutes. The gallerist Tim Neuger, who gave him his first solo show in 1994 at neugerriemschneider in Berlin, described a process in which Majerus would play video games for two or three consecutive days, fall asleep on the spot, wake up, and immediately continue to play, before turning to painting and spending another two to three days working at the same feverish pitch. There were intermittent fasts, time spent reading and writing, when he wouldn’t paint at all. During these periods of accumulation, he filled himself to the limit before releasing all of it into his paintings in long, continuous sessions.

LAURA OWENS, Artist: Michel had an innate sense of the progression of culture and its use of appropriated images. It came out of Pop Art and has kept expanding to the point where now you can make a novel through cut and paste. His work already had the open-source feeling of ubiquity, of things circulating – with more and more magazines, more and more places to see things. It felt like things were in circulation a lot quicker, not just on screens but everywhere.

I always imagine Majerus locked into alternating fugue states between painting and gaming, perambulating between the two sides of his room – one half of the space an unfurnished living room, save for a Nintendo 64 and PlayStation on the floor, a small television set framed by oversized speakers, and the cables spread into rivulets on the raw parquet floors. The only artwork was a Hackers (1995) movie poster depicting Angelina Jolie, her pixie cut, her face scored with cipher, the title’s pixelated typeface a near facsimile of the wry, clipped phrases that appear in his paintings. Majerus’ text and the poster share the same source as the party flyers and techno album covers of the time. Against a wall are piles of manga comics and copies of Electronic Gaming Monthly (EGM) stacked several feet high, a leering Buzz Lightyear figurine at its precipice.

In the mid-1990s, the covers of such video game magazines as EGM already staged the collision between two-dimensional and three-dimensional, with the flat, hand-drawn characters of comics and photography and the avatars of an emerging three-dimensional gaming world all sharing the same space. Perhaps these graphic designers were the first unknowing painters of the aesthetic we now associate with Y2K. They were already locked in the struggle to represent the movement of digital screens on the flat, atavistic plane of a magazine cover. Their struggle was something native to Majerus; he captured the exact moment when the first generation of its kind disappeared into their screens, controllers in hand, for every waking minute of their day.

His surfaces aspired to the speed at which gaming processors conjure images; the Warholian desire to paint without a paintbrush; to remove the artist’s hand entirely and work through surrogates, machines, prostheses. The use of a game controller translated uncannily into the bravura of painting and the absorption of references wholesale from the past, left almost unchanged: the overlapping 2-D and 3-D elements of the graphical user interface; the blinking power-ups; the chyrons; the appearance of hostile characters in a receding landscape and the force vectors that swirl around them, dissolving into a show of light effects on the screen as if the world were suddenly rendered flat and without depth. It’s entirely possible that the speed at which he worked better enabled him to represent speed.

Majerus liked fast things: Donkey Kong; data flows; short, clipped phrases floating like lines of broken code, such as “never trip alone always use 2 player mode” or “mace the space ace,” spoken as quickly as possible with all the glibness of a computerized voice. In the slick world of the Y2K era, everything looked fast. Things appeared and disappeared quickly. I am reminded of those high-tempo slaloms through the nocturnal marketplaces of Wong Kar-Wai’s films. Everywhere, light streaked, objects blurred as if racing by ... things that had blinked slowly, then blinked quickly, and time itself moved faster. Moreover, Majerus’ work was to be received with a certain speed of apprehension, too: a glance across a surface, the reading of paintings at the speed of a scroll, the quick recognition that something was cool – that it felt contemporary and immediate, hard-wired into everything around it.

I imagine the other half of Majerus’ apartment as a painter’s studio masquerading as a construction site. There is a perforated metal floor that he steps onto as he crosses the space, the same kind with which he lined the atrium at Kunsthalle Basel in 1996. There are fragments of scaffolding lined with aluminum panels, some painted over, fluorescent, their contents blinking like screens, while others are left raw and exposed, walls in a high-tech office. He inhabits a room that anticipates the reflective sheet-metal interiors of certain luxury retail spaces in the 2010s: the Balenciaga stores of Demna’s tenure; the work of Arquitectura-G for Acne Studios; the industrial detritus of the spaces OMA/AMO has created in collaboration with Prada.

PETER PAKESCH, Curator: I was pretty blown away by Michel’s nonchalance when it came to his heroes. He immediately communicated on an eye-to-eye level. His personal pantheon of great artists evoked in me the idea that he understood painting as a game of chess. What combination would work? What possibilities did he have? He played chess with the great ideas of painting – and by taking this game seriously, he discovered that some of the best moves hadn’t even been tried yet.

TIM NEUGER, Gallerist: Michel once told me that in New York he wanted to meet Julian Schnabel, but he didn’t have his number. So he looked in the Manhattan phonebook, where he found dozens of Schnabels. He called them, one after another, until he finally had Julian on the phone.

INGEBORG WIENSOWSKI, Art Critic: When they met the next day, he wanted to talk to Julian about his own paintings! It didn’t occur to him that this could irritate Julian. But Julian was polite: he told Michel that his paintings reminded him of David Salle and Basquiat. And what did Michel answer? “And yours look like Beuys and Twombly!”

Kunsthalle Basel was not the first time that Majerus refloored an exhibition. In 1994, he replaced the gallery floors with asphalt at neugerriemschneider. He also had a penchant for hanging his paintings from large fragments of scaffolding. In 2000, he painted a 400-square-meter skate ramp in Cologne with a litany of his signature motifs. The skaters moved like images across a massive screen. This project was as much about placing as large a painting as possible in the mess and activity of the world as it was about making an iconic skate ramp. It appeared the same year as a skate bowl designed by the art collective Simparch for the Hyde Park Art Center. The same bowl traveled, via documenta11, to its eventual home at the Supreme store in Los Angeles with a seamlessness that, surprisingly, neither the art world nor the skate world remarked upon. Majerus was always uncannily contemporary.

His installation work has often been misread as a desire to relocate the impedimenta of construction sites or the street to the white cube as a democratic gesture; a disruption of the division between the “high,” “sacred” space of the gallery and the world around it, much in the same vein as Michael Asher’s removing the front doors of the Pomona College art museum in 1970. Majerus was more than aware of the precedents set by such artists as Asher. However, these works behaved more as quotations, like much of the art historical material in his practice, rather than as actions with the same effective political ambitions.

If anything, I suspect that Majerus must have also been reacting to the total immersion offered by first-person shooter video games such as Quake (1996) – which was scored by Nine Inch Nails – or GoldenEye (1995), with their infinitely unfolding corridors of thin, texture-mapped walls. He must have noticed the clipping errors when characters became trapped in a wall, as if delivering on the promise of consubstantiality between figure and ground that Renaissance portraiture aspired to – figures who seem almost formed from the sedimentation of the walls behind them.

As he moved from one side of the studio to the other, Majerus must have experienced all the attendant side effects of time spent continuously in front of a screen – for paintings are screens, too. There was bleed from one universe into another, all the crudities of mid-90s CGI – the avatars of Super Mario or Buzz Lightyear, the light that falls according to the anomalous rules of physics that govern their gravity-less world, the neon glow of words and numbers leaping across the studio and onto the canvases and aluminum panels on the other side of the room. I imagine that the process Neuger described, back and forth between gaming and painting, was an effort to migrate that immediacy from screen to screen. There were also presumably the moments of simultaneity when Toy Story or Mobile Suit Gundam Wing (both 1995) played while he worked, or periods of lassitude in front of a painting that he spent face down in a Game Boy. The curator Peter Pakesch once said that he identified Majerus with his characters, such as Super Mario or Buzz; he referred to him as “Super Michel.” In those installations, with their paintings mounted to fragments of scaffolding, perhaps Majerus imagined he was constructing a virtual world and those silkscreened characters were his avatars.

And what of the strange plasticity of vision from living both ontologies as fully as possible, artist and gamer. To be sure, gaming is very much an ontology, a form of life as immersive as a monastic order replete with its own distinctive visual codes, heroes and hierarchies, morality, and sexual politics. One lives as a gamer just as one lives as an artist. Majerus was part of the first generation wherein it was possible to live as both at once.

At the very beginning of his autobiography, Speak, Memory (1966), Vladimir Nabokov described a friend of his who suffered from chronophobia. He experienced mortal fear when watching homemade movies that were made right before his birth. In front of a screen, with a projector clicking terrifyingly in the background like a metronome, his friend saw the world of his adolescence virtually unchanged from his memory of it – the same house, the same trees, and the same faces, save one detail: he himself was palpably absent. His mother waving at the camera from an upstairs window suddenly resembled a goodbye. The new cradle sitting empty on the porch, awaiting his birth, reminded him of a coffin. In his panic, he found that he could not distinguish between the world that came before his birth and the one after his death. The identical voids on either side of his life joined hands, and time became a spherical prison, a brief release of light in an infinite black.

Nabokov used this anecdote to illustrate the uncanny relationship between adolescence, memory, and death. This conjunction is something that artists who deal in the iconography of childhood know and exploit to tremendous effect. These artists – from Warhol to Polke – realized how advertisements, cartoons, mundane household products, stuffed animals, celebrities, television sets, Polaroids, and (of course) home movies have something funereal about them. In Renaissance paintings, the nativity and the crucifixion often exist within the same field of vision, even in the same paintings; the manger where Christ was born and the cave where he was briefly interred after his death mirror each other. In art, one often gets at death by going backward, through childhood, into the void. In this same vein, I think of Gerhard Richter’s grayscale paintings from family pictures, smeared by the vagaries of memory, and Mike Kelley’s arrays of stuffed animals banqueting around an unfolded napkin.

Of course, Nabokov insisted (with typical Nabokovian hauteur) that he possessed the familial gift of unmediated access to his past. He seemingly could recall the obscure details from the wings of a butterfly on a summer’s ramble at an age when most children wandered in a haze of half-formed consciousness. Yet even he projected the traumas of his exile, tropes from Maupassant and Proust, and the gallery of types he must have witnessed in Max Ophüls and Jean Renoir films into his childhood. He participated in the interwar nostalgia for the aristocratic graces of the Belle Époque, even as the shadows of Europe eviscerating itself cast themselves across his memories. If Majerus’ work vaguely unsettles us, it is because something sinister always hides in the penumbra of even the most luminous of beginnings – the very darkness that we send back into the infancy of the internet era from these latter days of surveillance, paranoia, and online hate. Majerus died tragically, in a plane crash, at age 35, on November 6, 2002, during a flight back to Luxembourg, and perhaps it is this detail, amid so many others, that gives so much of the work a brooding, meditative undertow ... as if all those bright, liquid paintings have the brevity of the work and his life as their ground.

Credits

- Text: MAHFUZ SULTAN

Related Content

032c Issue #43 “CULTURE CRISIS. Therapies for the confused” Summer 2023

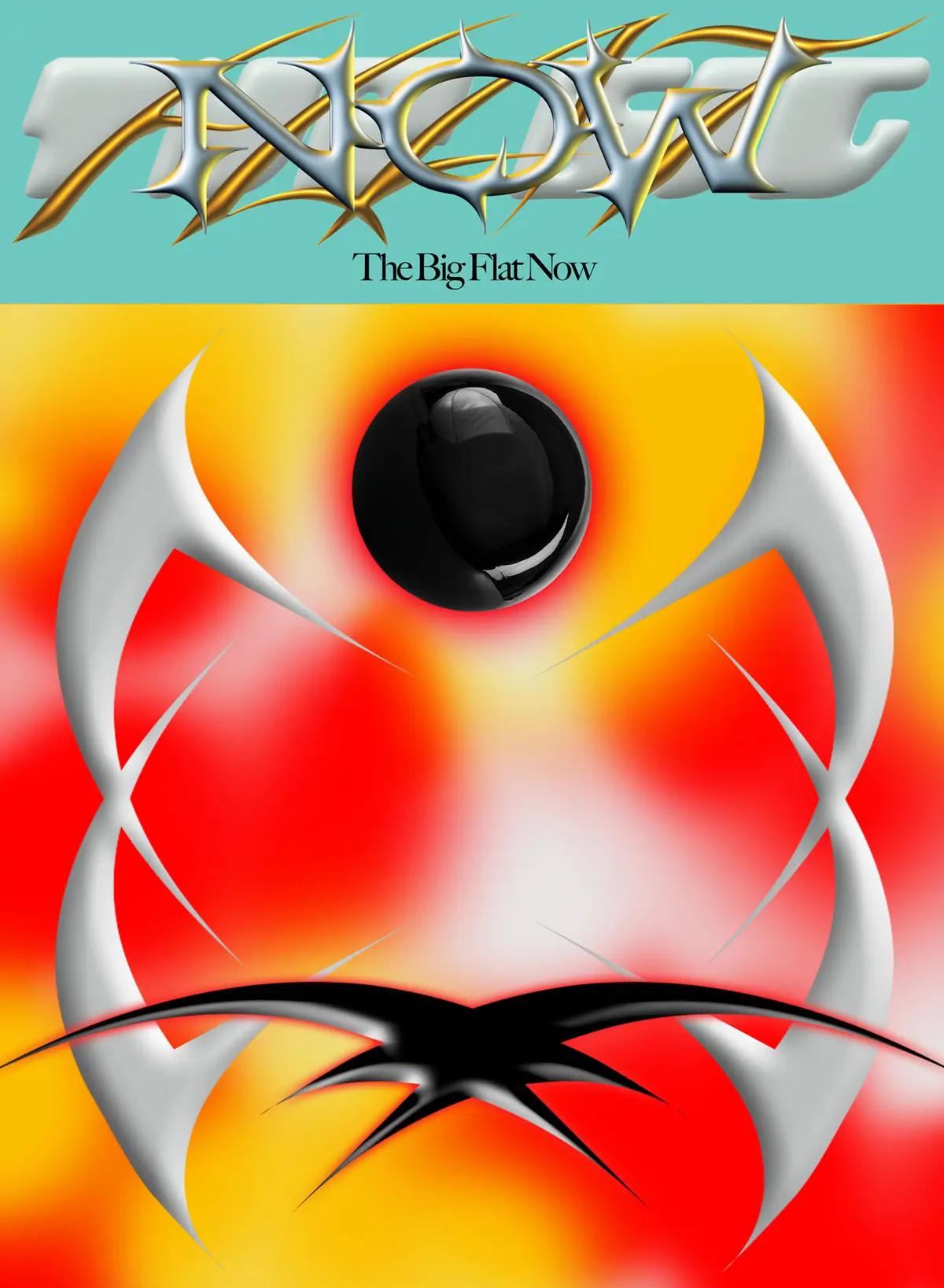

We regret to inform you that there is no future. Nor is there a past. Music, art, technology, pop culture, and fashion have evaporated as well. There is only one thing left: THE BIG FLAT NOW.

Image Spamming with Paul Hameline

“DEVILS ON HORSEBACK” Curated by Claire Koron Elat and Shelly Reich

Sarah Lucas to Massimiliano Gioni: “I Didn’t Want a Boring Life”

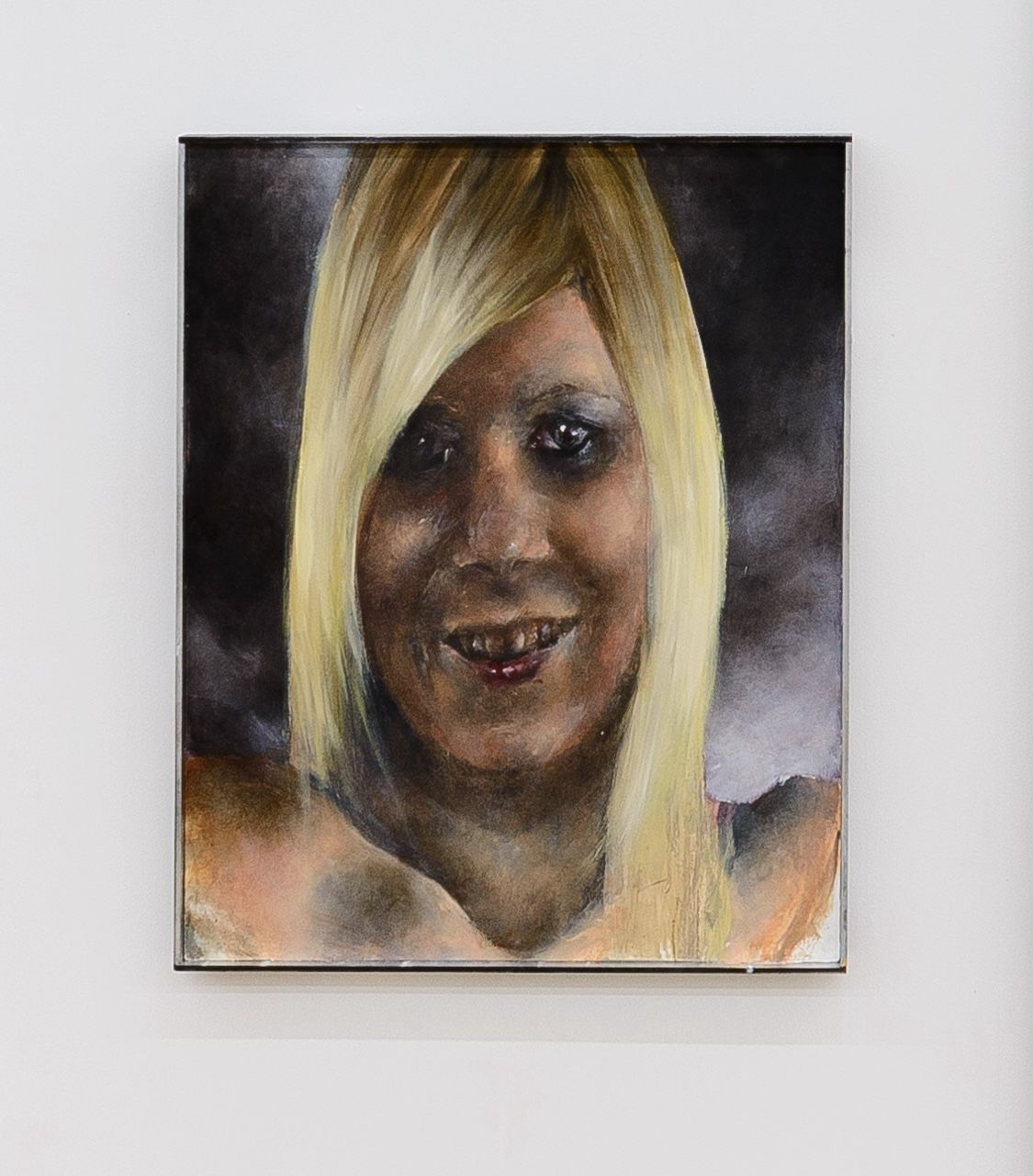

“We Should Get Her Flowers” by Ana Viktoria Dzinic

The Play-Doh Bunny: A History of Playboy

“Mother Mary Is the Juiciest Tomato of Them All” — A Retrospective of Nun-Pop artist SISTER CORITA