The Best Club in Europe Is in Wuppertal

|SHANE ANDERSON

There once was a city that was the epicenter of the German textile industry. With its high-quality fabrics, dyes, and chemicals, Wuppertal was world-famous during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century for its ribbon weaving, linen, and silk.

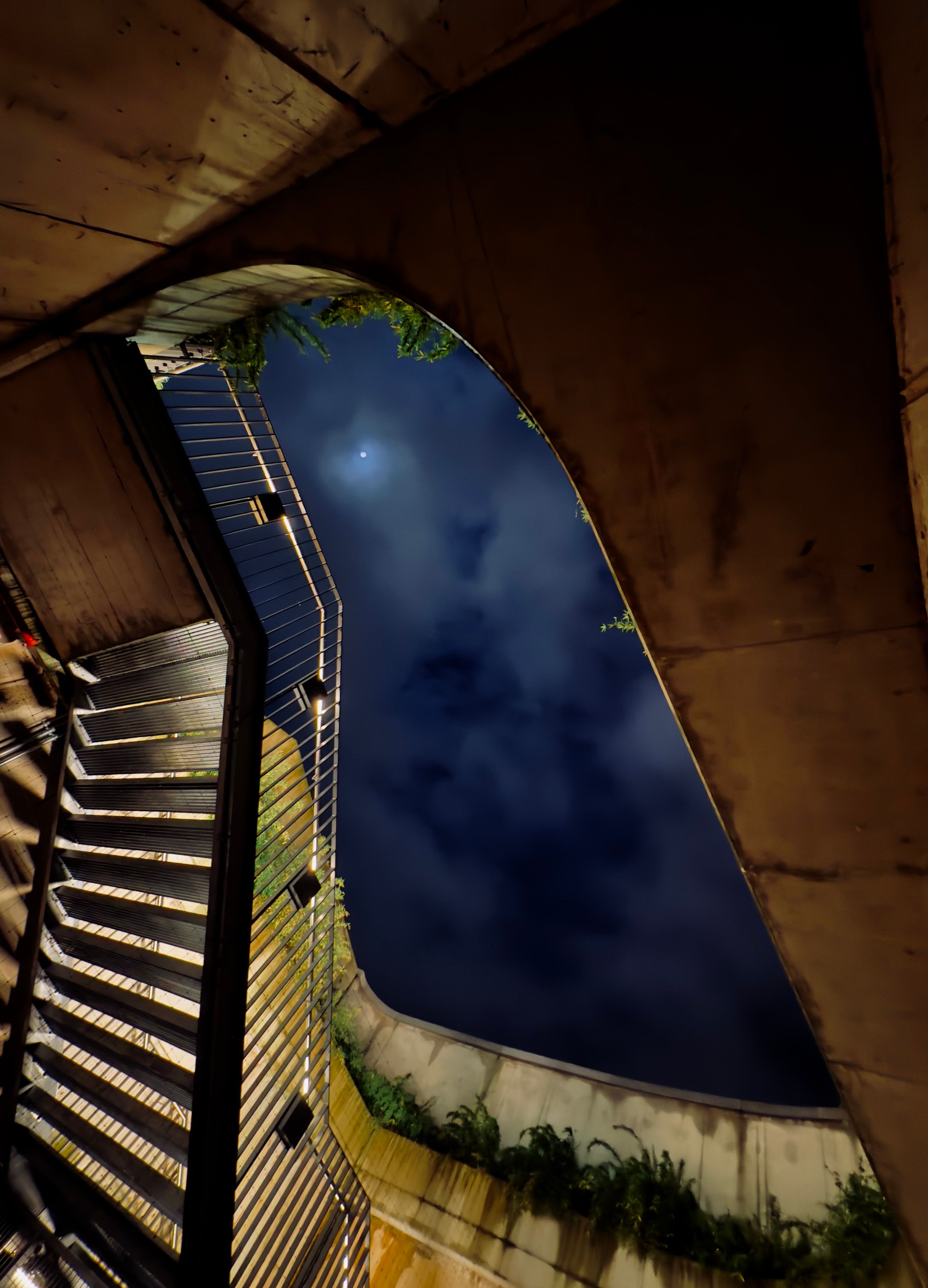

Open Ground entrance. Photo courtesy of Zenker Brothers

It wasn’t only clothes that set Wuppertal apart from other cities during the Industrial Revolution, however. Also finding their origins in Wuppertal are multinational companies, such as Vorwerk, Knipex, and Bayer; the last of which pioneered synthetic dyes, including the indigo used in jeans, and pharmaceuticals in their factories and labs in the city—fun fact: both aspirin and heroin were invented in Elberfeld (now part of Wuppertal).

During this time, the city was wealthy, boasting one of the longest stretches in Germany, if not Europe, of opulent mansions on a single street; as monied textile manufacturers, industrialists, and bankers built hundreds of villas in neo-Renaissance, neo-Baroque, Art Nouveau, and historicist styles in the Briller Viertel. As elsewhere, such affluence led to technical innovations—including the suspended monorail, the “Schwebebahn,” which commenced operation in 1901 and remains unique in the world to this day—as well as a flourishing cultural sphere. It was here that Dada poet Else Lasker-Schüler would be born as would philosopher Friedrich Engels, whose socialist thought was just as inspired by the inequalities he saw in Manchester as it was by the industrial exploitation he witnessed firsthand in Barmen (now part of Wuppertal) at his wealthy family’s numerous textile factories.

And while it is true that Wuppertal would later be home to other important cultural figures, such as choreographer Pina Bausch, filmmaker Tom Tykwer, collector Christian Boros, free jazz saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, and 032c editor-in-chief Joerg Koch (😉), amongst others, the city quickly declined in the mid-twentieth century due to globalization and automation. Later, it experienced the same brain drain that affected most Western German cities once the German government relocated to Berlin after Reunification. As it turns out, most of the aforementioned personages bid adieu to Wuppertal at some point—mostly for Berlin. The only one to have stayed was Pina Bausch, whose loyalty is repaid with murals on city walls and local coffee roasts named in her honor.

Thus, when the German weekly Die Zeit declared that “Wuppertal is the New Berlin” on March 5, 2023, it felt like a reach. This quaint yet impoverished city is full of empty storefronts and shattered dreams, happy to speak of its glorious memories while insisting that it isn’t provincial (which is oh so provincial). Nevertheless, this hyperbolic headline was welcome news to me. I had just moved to Wuppertal from Berlin at the end of January, and whenever I told anyone where I was now living, they’d inevitably ask, “Where’s that?” My answer stopped being “near Dusseldorf and Cologne,” and became “it’s the new Berlin.”

Open Ground construction site. Photo courtesy of Open Ground

Sarcasm aside, I couldn’t find anything that resembled the capital I had just left after nearly two decades of residence, except Das Loch and Utopiastadt, which resembled great bars in Neukölln in the late naughts. Otherwise, though, Wuppertal only resembled the myth of Berlin—cheap Altbau apartments, lots of available commercial space, and possibility, possibility, possibility. What was especially missing was something very fundamental to the capital, something that had made it special for decades upon decades. Namely, world-class clubbing.

All of this changed when Open Ground opened its doors in December 2023. The club, which is located inside an underground bunker a stone’s throw from the main train station, has since hosted internationally recognized acts, such as Floating Points, Joy Orbison, Ben Sims, Chez Damier, and DJ Storm amongst others, to play on its Funktion 1 sound system, whose impeccable sound has received much praise. The brainchild of Markus Riedel and Mark Ernestus (of Hard Wax Records and Basic Channel fame), the club is also notable for its wide music spectrum—dub, house, techno, jungle, and grime might drop at any point—and its lowkey, embracing vibes. When a friend asked me what Open Ground was like, I replied, “like Berghain before the memes.” And so, who knows, maybe Wuppertal is the new Berlin? Or will be.

I spoke to Riedel and Ernestus in early February about Wuppertal being the worst of news and why every room is a problem.

SHANE ANDERSON: You’ve been open for just over a year now. How are things going?

MARKUS RIEDEL: January is normally a very slow month in club culture, but it’s been good for us. That’s a relief because it’s a really difficult time for clubs, some of which are fighting for their existence.

There was a phase last spring where we were very new and still a little insecure and went from running both rooms every Friday and Saturday to just one, but soon we understood that the two nights cannibalized each other and having only one floor gave people less incentive to attend either night. So running both rooms just on Saturdays would be the better formula. But we already had our plans laid out for six weeks. Things only changed in July, and since then it’s always been a good party with both rooms open. There were always around 400 to 600 people, and for some of the bigger evenings like Floating Points and Joy Orbison, there were more. I’m actually optimistic. Open Ground is becoming more and more packed.

SA: How was this past weekend?

MR: It was a good party [on February 1, 2025] with a good atmosphere. There were only 350 people there, which isn’t a lot normally. But it’s a good number for house music, which is difficult in Germany, except in Berlin. The audience was very appreciative until the end.

SA: When’s the end?

MR: The plan is to close at six but if it’s really full, we usually extend it to seven. I think this will become the norm. The Perlon night is coming up [on February 14, 2025], and from then on, we only have very big lineups. I don’t think there will be a night with less than 600 people for the foreseeable future.

Open Ground entrance near Wuppertal Train Station. Photo courtesy of Open Ground

SA: What’s been the feedback from the DJs?

MR: Without exception, the feedback has been amazing. Everyone’s really happy with the sound, the team, how they are treated, and how the whole organization is run.

MARK ERNESTUS: People are very impressed and very grateful—sometimes even saying, “I can’t play in this or that club after having seen what’s possible.”

MR: DJ Mantra was on BBC 1 and spoke very highly of the club, saying the sound was emotional. It was like a prophecy and now Open Ground is not only making the rounds in the scene in Germany, but also in England. But it took a while for them to understand that it’s not a new club in Berlin. When we were just starting out, the typical talk about Open Ground was: “A new club in Germany? Where in Berlin is it?” We are now being taken seriously all over the world though. We’re getting an insane number of requests, and increasingly from very famous DJs.

SA: But why did you choose to open a club in Wuppertal?

MR: A couple of coincidences. The first coincidence is that when the city was thinking about activating the bunker, their number one wish was a club. The second coincidence is that the city called my brother, an entrepreneur in Wuppertal, who has experience with events, and asked him if he was interested. The third coincidence is that I had moved back to Wuppertal four or five years before that. When my brother told me about it, I called Mark right away. And we started talking about whether it makes sense to open a club in Wuppertal. It was clear right away that, if we did, we would have to do things very, very right. It couldn’t be just another techno club. It would have to be well curated with a broad spectrum. But we also knew the acoustics have to be right and that the acoustics in the bunker would be a problem.

ME: The acoustics are a problem in every room, it’s not bunker-specific. And then, of course, we didn’t think of opening a club in Wuppertal, the space was offered to Markus and Thomas [Riedel]. And it’s not just any space, it’s a spectacular space that’s only just some meters away from the main train station and there are no apartments nearby, which would lead to noise problems.

At first, I’d joke, the bad news is Wuppertal, the good news is the region. I don’t mean that as a dig at Wuppertal but more that any city of that size on its own is too small for such a carefully curated club of that size. Nevertheless, the city is part of the largest metropolitan area in Germany, if not Europe. Cologne is 40 minutes away by train, Düsseldorf is less than 30. And in the other direction, you have the whole Ruhr area, Dortmund and Essen. And then, the club’s about 2.5 hours away from Amsterdam, Brussels, Frankfurt, and about four hours away from Berlin and Paris.

MK: Wuppertalers always have this tendency to defend and thereby perpetuate their provinciality. It’s as if they have an inferiority complex and try to compensate it with the Schwebebahn and Pina Bausch. I think you can talk about the city with more self-confidence and be natural about it. It has a lot going for it. Rents are cheap. There’s a lot of space. It’s quite diverse. It’s quite green and yet not far from Cologne and Dusseldorf. And the topography and buildings are interesting. But you still have to be realistic. It’s not Berlin.

ME: You can be a local patriot without being provincialist—or as they say, “think global, act local.”

SA: Are many people traveling to the club from elsewhere?

ME: There are three layers of guests who make up the mix: locals, people from the region, and people who will travel from anywhere. The weight of each night depends on the lineup and whether the label or artist has a very loyal fanbase.

MR: A lot of people from Cologne have told me that if they want to go out, they only come to us.

LEFT: Open Ground entrance. Photo courtesy of Open Ground

RIGHT: Open Ground outdoor queue. Photo courtesy Open Ground

SA: I’m curious about the decision still. Opening a club in a former WW-II bunker that is still buried underground is wild. Could you talk about the construction phase?

MR: Mark and I had a very clear idea of what we wanted, not only in terms of the rooms and the acoustics, but also the design and layout. In the first phase, there was only the one room, which is by far the largest area, and had ceilings that are 2.7 meters high.

ME: That’s just the initial height of the room, which could vary based on the design.

MR: That was also before the sound absorption—or acoustic absorbers—which was absolutely essential, and the raised DJ booth. We wanted to have a stage, which quickly add height. So, we needed a higher ceiling, at least where the club rooms are. That was the first big hurdle, and we had to be creative. We considered lowering the floor, but it’s made of one meter of concrete and beneath that is the river Wupper’s gravelly soil. The structural engineer said that if we lowered the floor, we ran the risk of flooding. So, that obviously wasn’t an option.

We decided to see if we could saw the ceiling out. We found a company that converts bunkers into lofts and saws concrete blocks out of walls and ceilings. It was during this initial excavation work that we found the water reservoir, which houses our ventilation system and the small club room. We already had the suspicion that something was there from the blueprints, but it was just a dashed line on the blueprint and no one in the administration could confirm that it existed. But at some point, we found a rusty hatch under a bit of earth, and there was an 80-by-80-centimeter hole. That was the only access to the trapeze-shaped water reservoir, which had a ceiling height of 3.5 meters, where we could put the ventilation system. After this discovery, we had to abandon our entire plan and reapproach the city administration since it was such a massive change. But in the end, it worked out.

SA: How long was the entire process?

MR: From the initial planning to completion, seven years. And it was quite tricky. The bunker was made up of a lot of smaller rooms, which we wanted to open up. Since we removed so many load-bearing walls, the structural engineer had to recalculate, and we had to create a new structure. The floor was a problem too. It was very uneven concrete. We decided to lay mastic asphalt, which is an excellent surface. It’s not as hard as concrete, but it’s very robust, easier to dance on, and will last forever.

SA: That sounds like it cost a ton of money.

MR: It did.

SA: What fascinates me is that you decided to keep going. That even after the first phase where you noticed that the ceiling was too low, you didn’t say, “Oh well, it’s just not meant to be a club.”

MR: At first, we had a lot of motivation, of course. I never lost it, but my brother started having doubts as it became more and more expensive. I think that if we would have known before how much it was going to cost, we definitely would have given up. But these costs came bit by bit, and so we were always in a situation where it didn’t make sense to give up. We were always at a point where we had to see it through.

ME: That’s how it goes with projects of such magnitude. If you had known what you were getting yourself into, you probably wouldn’t have done it. But in retrospect, you’re very happy that you didn’t back down. I’ve often felt that way in life and with projects. And it only makes sense to do such a project if you do it with consistency and really try to make a difference. Ideally, to do everything right. I don’t think any of us could have been bothered to just open the one thousandth club in Germany.

SA: It’s very courageous. And I think the same thing could be said of your programming, which can be quite experimental.

MR: To address that, you’d actually have to ask Arthur Rieger, who does the curation supported by Chris Parkinson. They both pursue the musical vision.

ME: I think it all goes back to the beginning. The motto was always to have an open program that is nevertheless never arbitrary.

So, during one of our first conversations, I said there are some factors that are difficult to influence. But there are factors you can. The first is to take the acoustics and sound seriously. If you do that, then you already have a striking and unique selling point. But the best sound in the world doesn’t mean shit if you don’t play really good music on it—otherwise, it’s not culturally relevant. And then the spiral continues. You move from perfecting the sound, music, and content to the whole experience—the door, the team, everything—and do it with consistency at a very high level. It's an adventure.

Original bunker space under Wuppertal's Döppersberg. Photo courtesy Open Ground

SA: Mark, you run Hard Wax in Berlin and are also active as a producer and musician. You also used to run Kumpelnest 3000 in Schöneberg. I understand how you became part of the project, Markus, but how did Mark come into the project?

MR: I worked for Mark for 20 years, first in the bar, then at Hard Wax, then in the office of Basic Channel, where I was the only employee. So, I was on this journey from the very beginning. But I was never really involved in the creative side of things—I never looked after the music at Hard Wax or was a DJ. I was always comfortable in the club scene and the Hard Wax environment, though. There was a phase in the 90s, when I went out a lot and often wondered whether opening a club would be a good job, since I’m very good at organizing things. I dreamed about it for a while, but then we had kids and moved to Wuppertal, and everything turned out quite differently. The idea was long gone, but my friendship with Mark was always there. Whenever he would tour with the band from Dakar [Mark Ernestus’ Ndagga Rhythm Force], they would stay here with us, sometimes spending a few days during a break in their schedule. Because of our friendship, it was completely clear to me that I would approach him about the idea. And then the rest came together quite quickly. We both clearly had the same desire and agreed on everything.

ME: And for me, who has been a DJ or been on the road with a band for many years, there have been many moments where I thought things could and should be done better. And that was also one of the incentives [to do it right].

MR: It was always such a shame. There were some great club nights where everything was perfect—the atmosphere, the crowd, the lineup—but the sound wasn’t. And that thought always bugged me.

SA: You’ve mentioned multiple times that the sound is the foundation for Open Ground. You use the Funktion 1 sound system. Why this one?

ME: When I talk to other people, it’s generally accepted that speakers are a never-ending journey. Every few years, you think you’ve arrived at the final destination, but it somehow always continues. I always loved Funktion 1 when I had the chance to play on it though. And so, there was no reason for us to keep doing research. We were very, very sure that Funktion 1 would go where we wanted to go. It should also be said that the room is at least as important as the sound system—you can’t separate them at all. It makes no sense to talk about a system if you don’t talk about the room. When you open a club, the acoustics have to be the first thing you think of.

SA: You’ve done a lot of work in that regard, installing plates that absorb the sound, making the music very crisp and clear, while the bass still rumbles through your body. It’s a real experience. And the experience of being in a club and dancing together seems to me to be very important at Open Ground. Is that why you don’t allow photos and tape over the cameras on phones?

ME: We weren’t sure in the beginning whether people in the region would accept this ban as they might not be as familiar with it as clubbers in Berlin—but were pleasantly surprised by how almost everyone actually embraced it right away. It was immediately understood that going to a club is an intimate space, and privacy should be protected there, especially since people post all kinds of shit on social media. It also fits with our philosophy that this is about a real experience that you can’t convey in a selfie. Just be there and live in the fucking moment.

MR: We don’t want people taking photos during the event and in the beginning, there was a strict ban, even for the DJs—even when the club night hadn’t yet started. I think this ban came a bit from the experience with Berghain and the idea that it’s good if you’re curious about a space and that it doesn’t really appear anywhere else. But we’ve loosened up a little. There are more and more photos by people and the DJs are also welcome to take pictures during soundcheck. You can’t really control it, and I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. But we really don’t want people taking photos during the club night because it’s just wrong and annoying. And if you start allowing it, then it’s not just the occasional person taking photos but a ton of people all the time.

Sometimes, though, the social media team really want something for Instagram, and I’ll discretely make a few video recordings. I’ll stand at the very back and try to discreetly film the backs of people for a couple of seconds. What has often happened is that people either cover the camera or speak to me—sometimes in a friendly way and sometimes quite rigorously. Some people accept it when I tell them I’m part of the team. But other times, they’ll go to the bar and complain that there’s an old man in the back taking pictures.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON

Related Content

Berlin’s Sonic Mecca

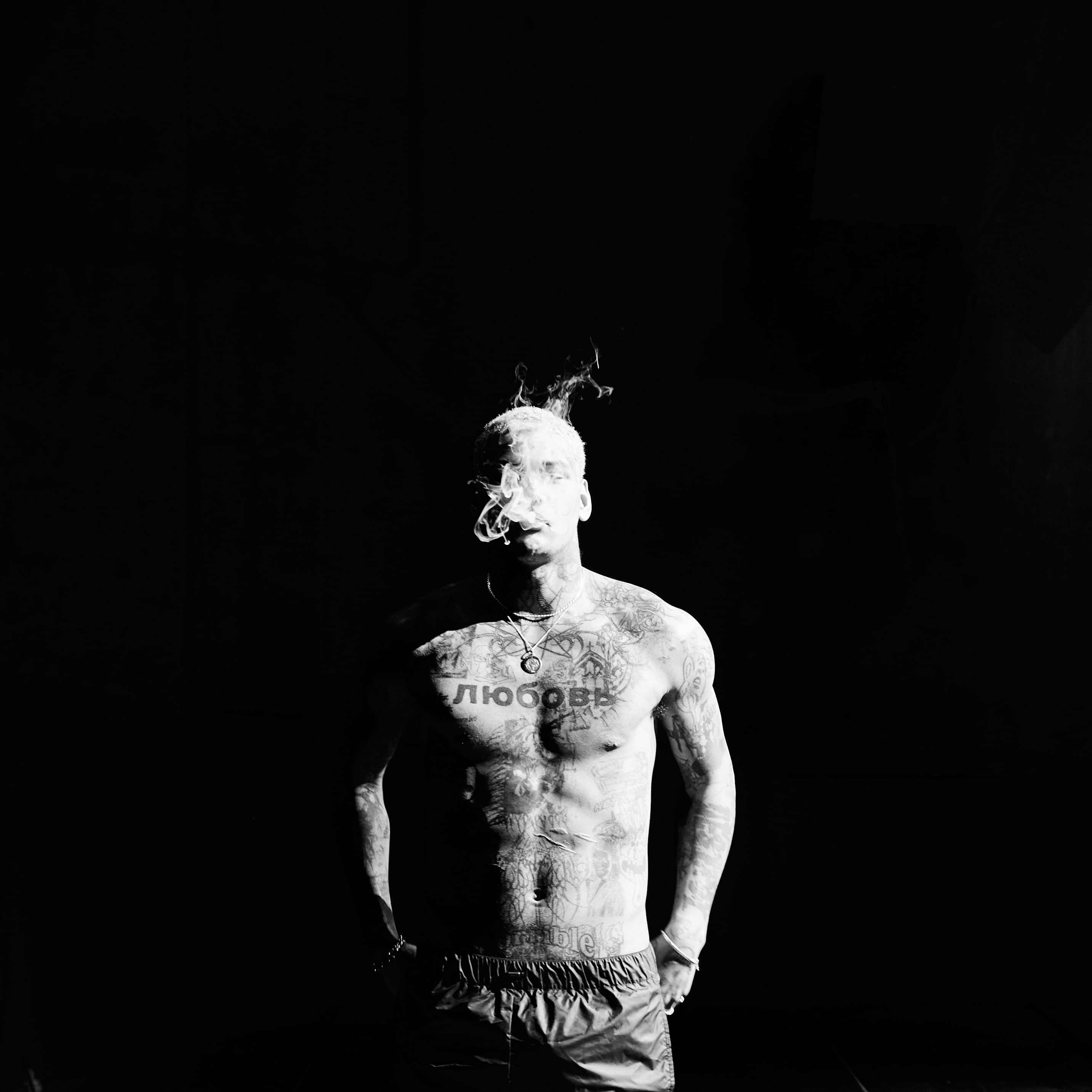

Thoughts on Ekkstacy in Berlin

All Nighter With Dalston Jazz Bar

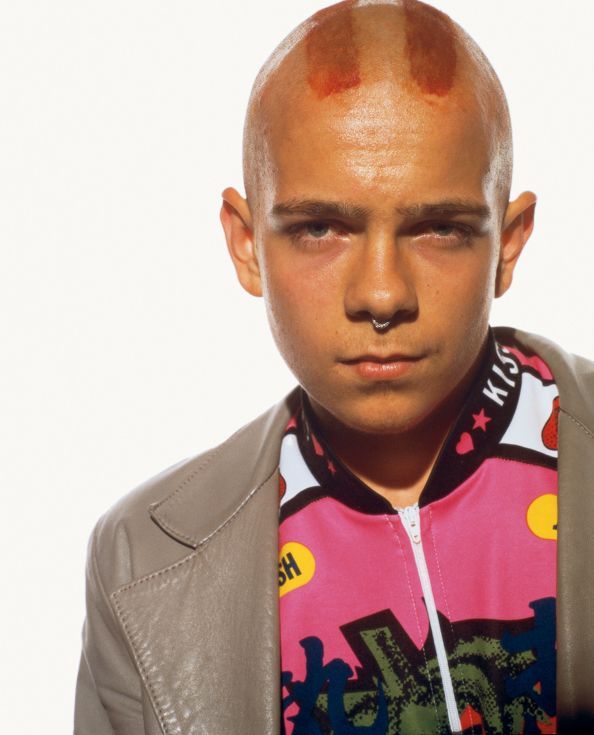

Brutalismus 3000: “The Secret Ingredient is Controversy”

A Specialist in Club Music: VTSS

Gated Nightmares: Herrensauna’s Cem Dukkha

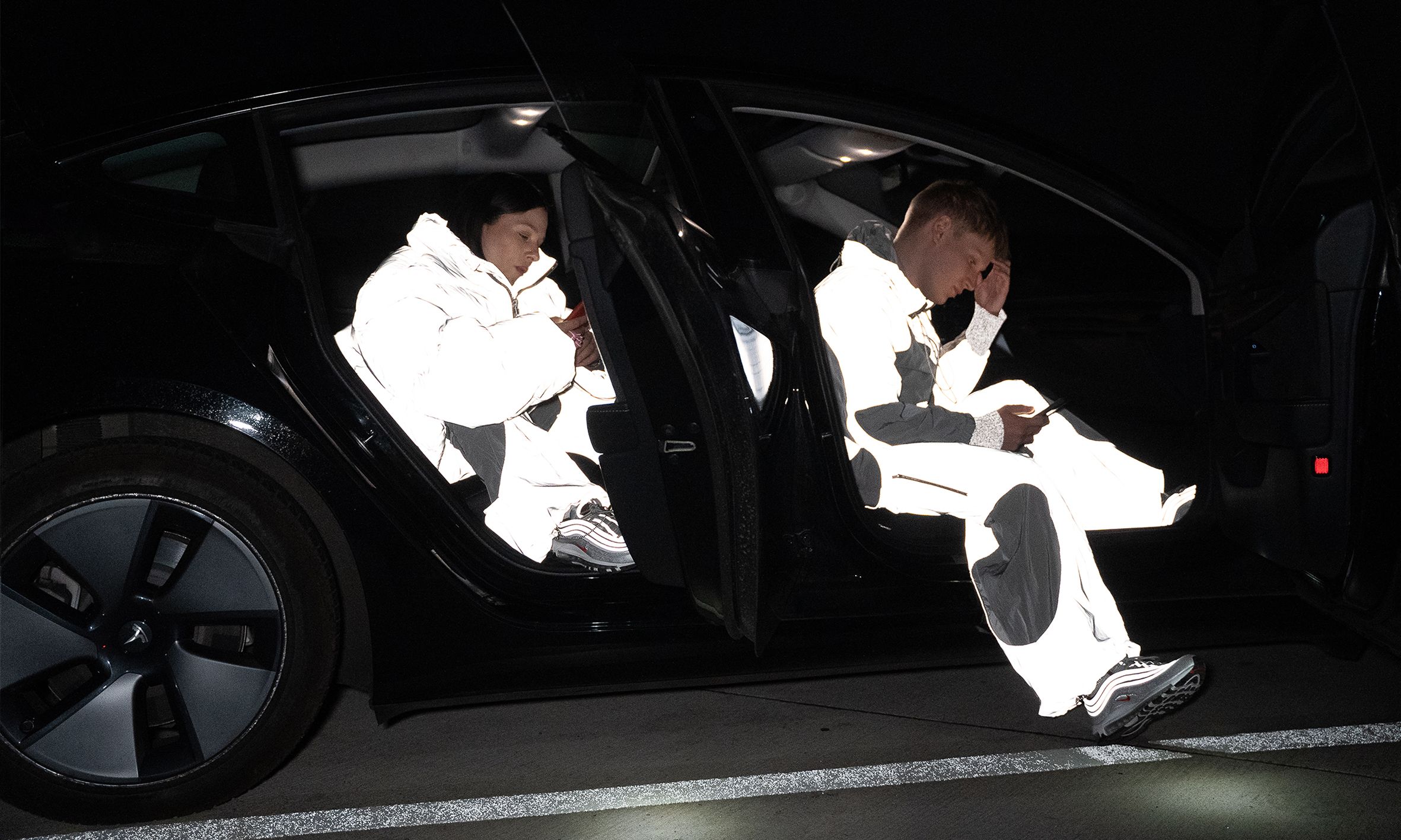

RAVE: Before Streetwear There Was Clubwear

Who Wants to Be a Human Jukebox? Richie Hawtin

“If this is hell then I’m lucky.” In the Eye of the Storm, Listening to DJ SCREW

Lust & Sound: Man About Town MARK REEDER’s Forgotten 80s Berlin

WESTBAM: You Need The Drugs

BIGGIE SMALLS — THEODOR ADORNO