Berlin’s Sonic Mecca

|Max Dax

Originally published in 032c Issue #41, the oral history of Hard Wax investigates the Berlin-based record store as a seismograph and pilgrimage site for emerging artists and subgenres.

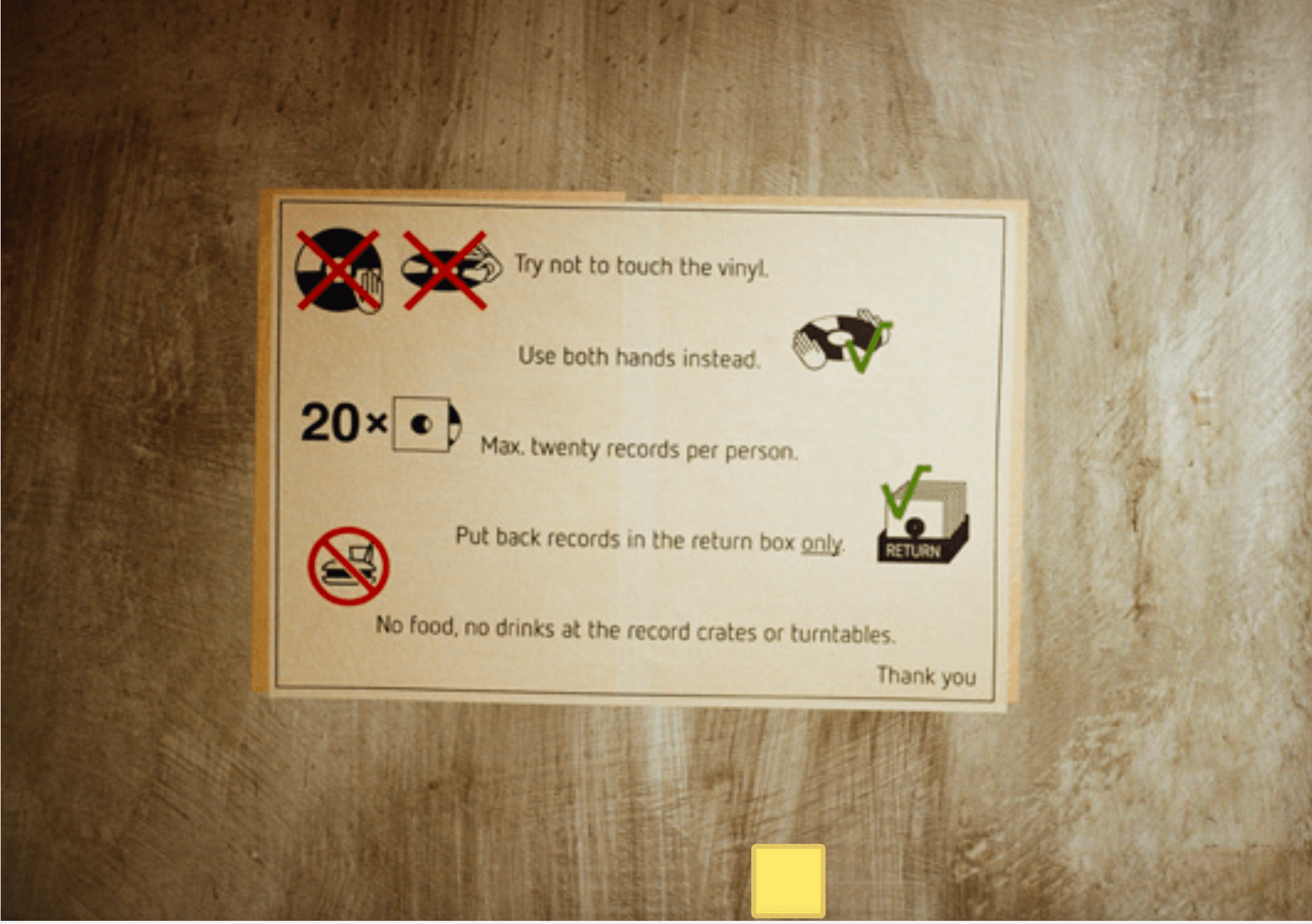

“If I had never met Mark Ernestus,” says pioneering DJ and techno producer Jeff Mills, “I would have lived in another city—or another country.” Ernestus is the founder of Hard Wax, a record store on Berlin-Kreuzberg’s picturesque Paul-Lincke-Ufer—and one of the most reputable outlets globally for techno, house, and dub. Tucked away from the street in a former factory’s courtyard, Hard Wax is both a site of pilgrimage and a seismograph for artists, incubating new talent and sub-genres for more than three decades. Visitors to this fortress of electronic music mostly observe silence, and photography is strongly discouraged—it is a temple, after all. But Ernestus breaks the silence here, speaking alongside pillars of Hard Wax for an insider’s oral history.

Characters, in order of appearance:

MARK ERNESTUS founder of Hard Wax, member of Basic Channel and Rhythm & Sound

MAX DAX writer, curator, author of this Hard Wax history

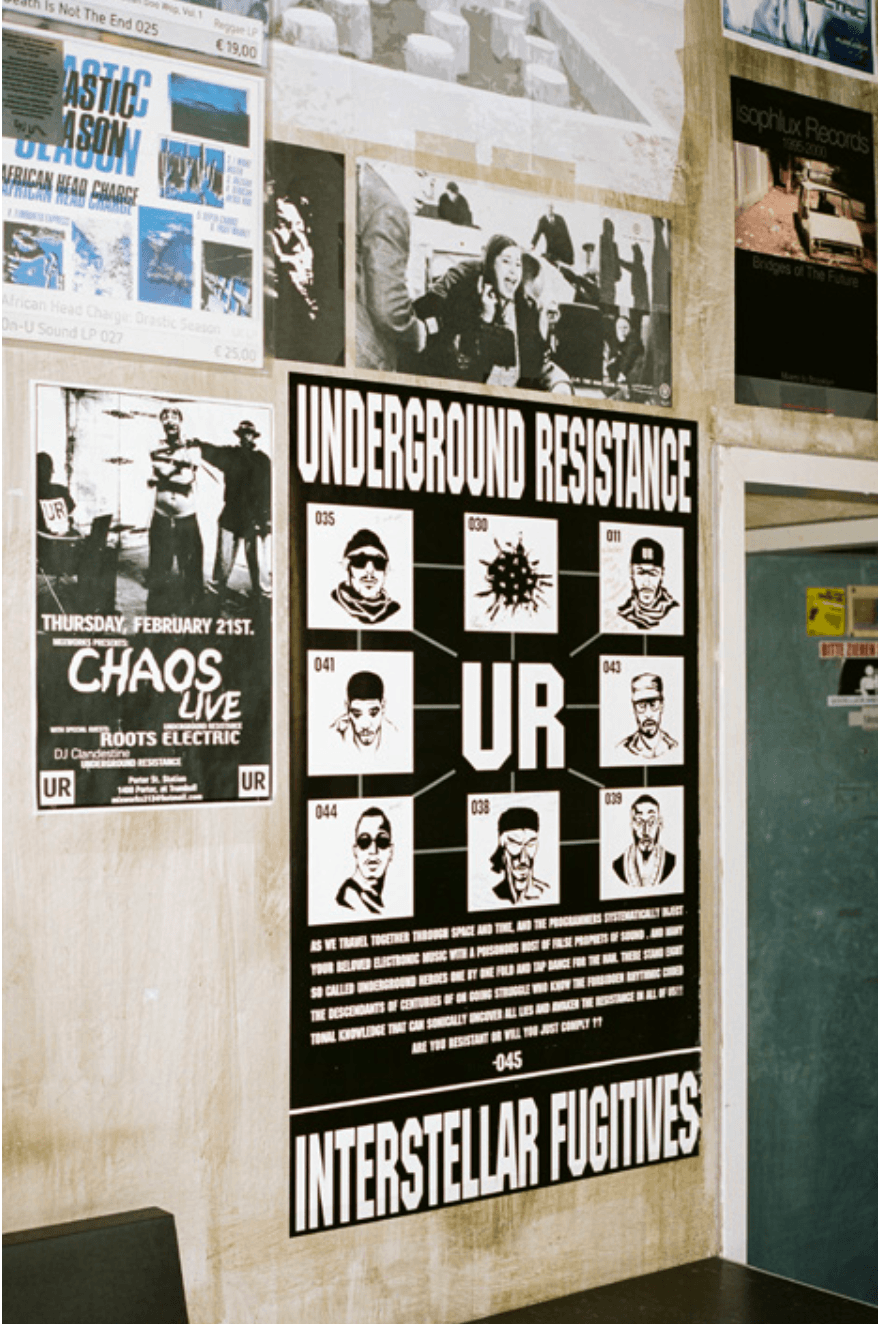

JEFF MILLS DJ, producer, founder of Underground Resistance and Axis in Detroit

SASCHA KNUDSEN current Hard Wax employee

BORIS DOLINSKI famed DJ, former Hard Wax employee

GERNOT BRONSERT DJ, member of Modeselektor and Moderat, former Hard Wax employee

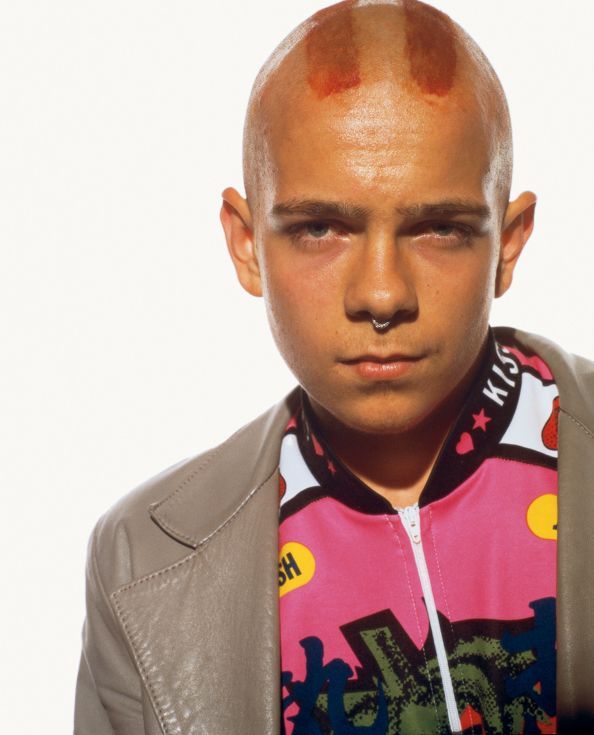

DJ HELL DJ, producer, former short-term Hard Wax employee

ELECTRIC INDIGO DJ, producer, former Hard Wax employee

MARK ERNESTUS: I’ve always been a music junkie. During my teens in the 1970s, I was hungry for cultural input that extended my horizons beyond provincial West Germany, where I was living at the time. Records were the medium that connected me to a more exciting and meaningful world.

MAX DAX: After the war, West Berlin was a bad place to pursue a career, but a great place to celebrate an alternative lifestyle with little money. It was a place where things could happen that couldn’t happen anywhere else in the country. And then, of course, if young men wanted to avoid being drafted by the Bundeswehr, they only had to show proof of permanent residency in West Berlin.

ME: I moved to West Berlin in the early 1980s, and I opened Kumpelnest 3000, a small bar off Potsdamer Strasse in Schöneberg, in May 1987. When I worked a shift at the bar, I would prepare two 90-minute mixtapes. I would maybe play each of them twice that night, but then they felt like they were already dead and couldn’t be played for the next shifts. Kumpelnest 3000 was successful, which meant I had enough cash to buy all the records I wanted, and after two years, I decided to leave the bar and open a record store. Being a record buyer, I was convinced that West Berlin needed another shop that was well-stocked and specialized in soul, funk, and house music, or what was called “Black music” in Germany at the time. That was my motivation to open Hard Wax. That, and I wanted to have direct access to suppliers.

MD: Hard Wax opened in the winter of 1989, in Kreuzberg’s Reichenberger Strasse. That was a pretty remote place on the eastern frontier of West Berlin. The address seemed even more remote after the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

JEFF MILLS: Before specialized and communal shops like Hard Wax in Berlin or Submerge in Detroit opened, you had record stores in the United States that were like insanely big supermarkets. They had salespeople, but these places were so big that you were left on your own to find what you wanted. The rise of shops like Hard Wax that focused only on house and techno music was a game changer.

ME: The sign on the window said: “HARD WAX. Black Music. Ankauf und Verkauf.” We sold a lot of used soul and funk records in the beginning, as well as reggae, dub, and hip-hop, and we had a small house section—the few records that were available at the time. And hardly any of them were original pressings.

JM: Small shops run by music lovers are places where people gather. These are the places where more serious people and the professional DJs dig for their music.

ME: The salesroom was a typical Berlin-Kreuzberg store in an old building: two adjacent rooms, with shop windows facing the street, that were connected by a wall opening. In the back, we had a small storage room, a packing table, a sink, a toilet, and more shelves. The whole store measured 68 square meters. We didn’t have that many records to sell in the beginning. But the compartments and the storage were eventually overloaded with stock. We never stopped building shelves; at some point, they were even above the sales counter.

MD: People like to claim that techno music substituted decades of rock domination in West Berlin overnight. The city did have a strong history of rock music—thanks to artists like David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Nick Cave and The Birthday Party, as well as Die Haut and Einstürzende Neubauten—but it also had a profound and long-standing disco and gay subculture. Some clubs were like meeting points or hubs, especially Dschungel and Metropol, and the scene that had formed itself around these clubs was very permeable and open. That was something really special about Berlin. To me, it was only logical that house and techno would be welcomed in a city with such a strong disco and gay scene.

ME: At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, there were weeks that felt like months or even years. Everything was changing so in- credibly fast; so many new things were taking place at the same time. This applies to the major political and social changes as well as to club music—house, techno, whatever you wanted to call it. Eventually, the important techno and house clubs opened up in East Berlin—Tresor, Planet, Walfisch—especially near the Mauerstreifen, in its many abandoned buildings. By then, the scene had really exploded, and interests had shifted: techno was big, and house was marginalized. I sometimes nostalgically look back to the openness, radicalism, and joy of experimentation that was possible under the term house.

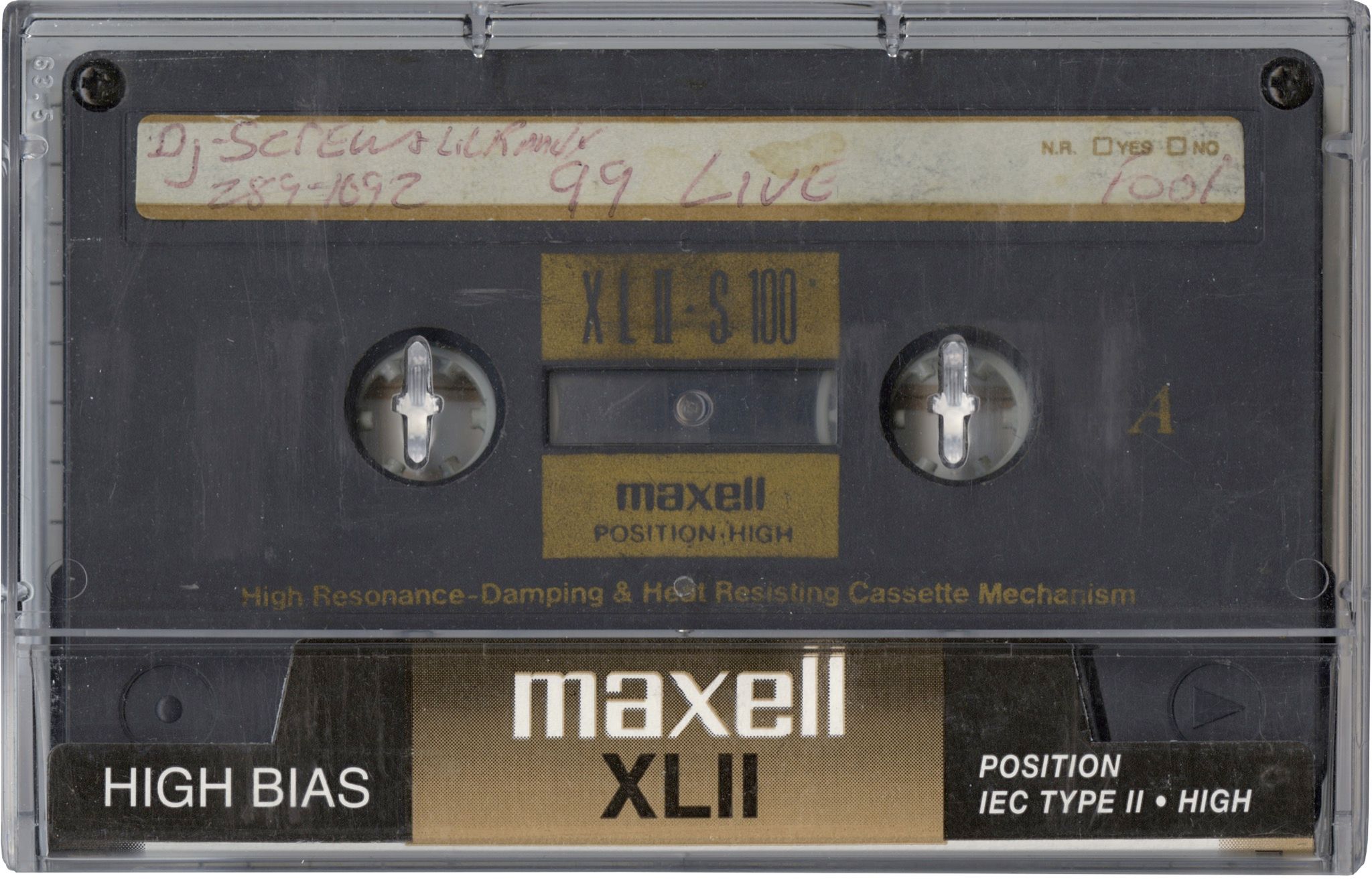

SASCHA KNUDSEN: I grew up in the GDR. I was 17 when Hard Wax opened, and I only knew music from radio stations. West Berlin had two FM stations that would air programs dedicated to house and techno music, where they’d play acid house or other subgenres for about three hours in a single stretch. Being limited to listening to the radio in the east, I hadn’t been exposed to the culture of buying and collecting records. Instead, I recorded tracks from the radio and made tapes. So even though I couldn’t buy records in the east before the Wall fell, I still knew I wanted to be part of this scene. And I knew that I wanted my own record collection.

ME: Detroit techno—and Underground Resistance, in particular—really hit the spot for us. By “us,” I mean everyone in the Hard Wax milieu: the staff, the DJs, and everyone else. We were particularly keen to make direct contact with interesting labels and artists in Detroit, because we felt like there was a special connection. The Detroit experience corresponded to the Berlin experience in a curious way. We thought it was nuts to sit in a restaurant with bullet holes in the window; they thought it was nuts to see World War II pockmarks and grenade hits on the façades of our buildings.

JM: Mark and his people were on their phones, calling US numbers to get all this music to Berlin. They were restless in finding new labels and new music to ship to Berlin.

ME: I had met Derrick May with my friend Boris Dolinski in 1990. Derrick had played in front of maybe 30 people at the second incarnation of the UFO Club, and afterwards we gathered the courage to talk to him. We told him we thought it was disgraceful that the event was so poorly attended. We also mentioned that I had recently opened a record store. He said, “If you ever come to Detroit, call me, here’s my number.” I don’t think he considered it to be a real possibility, but he definitely encouraged me.

JM: And they were traveling, too. Mark even flew to Detroit to meet us there.

ME: It was a freezing, foggy night when I drove into Detroit from Chicago in January 1991. In my excitement, I hadn’t bothered to look at a roadmap beforehand. I remember thinking: there’s always an exit sign for the city center, all I have to do is find that and take it from there. But that sign never came. I thought I missed the city. I decided to get off the freeway in my rental car, and I took the next exit. By chance, I exited on Gratiot Avenue, where Derrick lived. But then I drove the wrong way for miles and miles. I remember seeing five-digit house numbers. That was a first. Nowhere looked inviting to pull over, but then there was a McDonald’s restaurant with a pay phone out front. I dialed Derrick’s number. He didn’t remember me but said I should come over anyway. He was already a celebrity who was playing all over the world, but I guess it was rather unusual that someone would come from Germany to meet him. In those years, Detroit wasn’t a place where many would willingly go.

MD: That was the start of a very long relationship between the two cities. Funnily enough, there’s never been a direct flight between Berlin and Detroit.

ME: On my first trips to the United States, I’d often find whole boxes of records that were desperately sought after in Berlin but didn’t show up on any distribution lists. Some of the warehouses I visited were very chaotic. But that’s where it was worth spending your time: you could always find treasures in the chaos. The most amazing warehouse was Barney’s in Chicago, where Dance Mania and other labels came from. Barney’s had a small shop, but behind it was a huge warehouse full of records, hidden to the public eye. Ray Barney was very open, and I was allowed to move around freely. The warehouse was well structured, but there was one huge wall of shelves where I couldn’t make out any system or order. It was probably the return shelf, which remained unsorted over many years. That was a feast! I spent almost the entire day browsing this one shelf. At the end of my road trip, I sent back about 1,000 records from Chicago, New York, and Detroit.

BORIS DOLINSKI: Mark’s packages, as well as the packages from our direct distributors from the US, were sent by air freight, and it always took four to five days for them to arrive after the order was placed. Every Monday, one of us had to drive to the airport and process the packages in customs. Shipments had to have a minimum of 100 kilograms.

GERNOT BRONSERT: It was always special to unpack shipments from Submerge. You’d often find crumpled newspapers stuffed between the record boxes. Sometimes I would smooth them out—and the front page of a Detroit newspaper would appear. I always found that really touching, almost in a romantic kind of way.

JM: All the other shops in Berlin weren’t nearly as well stocked as Hard Wax. So, as a professional DJ, it was clear that you would go to Hard Wax first, and only then go to the other shops to see if they had something more that you could add.

ME: For the first four years, Hard Wax remained the only store in Berlin and East Germany specializing in house and techno. We weren’t the only store selling house records in Germany, but there was little exchange between the cities. The scenes developed quite independently and had very different directions. DJs rarely played outside their own cities back then. Frankfurt, Hamburg, Munich, and Cologne were far away.

DJ HELL: Mark was in the process of creating a serious network for techno and house imports in Europe. Jeff Mills would sometimes stay in Mark’s guest room when he was in town. Or Mike Banks would come to Berlin with a suitcase full of freshly pressed records—and deliver them directly to Hard Wax.

ME: You may be closer to the source if you have your own store, but if you really want to be independent from what the established importers have to offer, you need a connection to the sources. And this is where Boris Dolinski comes in. At the end of 1985, he threw a farewell party at Kreuzberg’s Oranienbar before moving to New York. That was a bigger deal back then. Nowadays we can easily stay in touch, and transatlantic flights have become somewhat normal. Anyway, five years later, Boris suddenly walked into Hard Wax, in the spring of 1990. I was totally shocked.

BD: I grew up in West Berlin’s nightlife in the 80s, and when I arrived in New York, I continued where I left off. I lived pretty deep down in Brooklyn at first, then in the Lower East Side, and finally in Harlem. None of these areas were gentrified back then; they were really run down. But that’s where I witnessed the dawn of a new era. House music was born. In 1986 and 87, clubs like the Paradise Garage had probably 2,000 people partying. They had high-end sound systems, and I was listening and dancing to music I had never heard before. It was euphoric. And that’s why I stayed. I also bought the music I liked at the clubs because I wanted to have my own record collection at home.

ME: Many of the records in Boris’ collection were the stuff of legend—things you had rarely ever heard or seen yourself. Boris knew every label and practically every record. He also understood the stories behind them: who produced under which monikers, which producer was also a DJ, which DJ played what records in which clubs, et cetera. Boris had an incredible amount of knowledge. He knew more about house than anyone else in Berlin.

BD: When I came back, I brought around 2,000 records with me. A friend of mine said, “You gotta check out Hard Wax.” So I spent a couple of evenings hanging out with Mark and his people and talking about house music, playing them records from my own collection. Mark said that he would like to order these records for the shop. He asked if I would like to work at Hard Wax. I was well-versed in the scene and spoke fluent English, which helped.

ME: It was a no-brainer. Boris had to work at Hard Wax.

BD: The first step was to reorder vast sections of my record collection for the shop—and to then systematically stock these records. Mark trusted me when I gave advice on house music and on the labels, producers, and distributors that were important. I then did all the communication with America. Back then you had to write faxes in English to order records from the States. That’s also how we bypassed the German and European distributors. I don’t want to know how many thousands of rolls of fax paper were used.

DH: Every month, we’d receive a fax newsletter from Miss Moneypenny, a very respected music journalist in New York. It contained reviews of new releases and reports from house parties in New York, Chicago, and Detroit. Whoever was mentioned in her newsletters gained immediate respect and recognition. These were long faxes, sometimes three meters long. You had to cut them with scissors. Miss Moneypenny sent out her techno diary to a hand-picked selection of record stores worldwide. Her newsletters were our bible.

ME: Ninety percent of all orders were placed by fax, which was an expensive medium. You had to pay telephone charges, and you had to constantly buy fax paper. When we started doing direct imports from the US, we had four-digit phone bills.

BD: Trust had to be continually built up and maintained with regards to financial credibility. Today you have credit cards and PayPal. Back then, you had to pay invoices via bank transfers, and there was always a span of days before the money would arrive in a US account.

ME: Everything moved very quickly once we started importing directly from the US. All of a sudden, we had large quantities of records that had only been known by word of mouth. The sudden availability of these records—many of which are still the foundation of house and techno—enabled a whole generation of DJs who were already waiting in the wings to start playing when the right clubs opened within the following year. The scene exploded.

ELECTRIC INDIGO: I ordered from the labels in Europe. I’d often get a call from the labels on Mondays or Tuesdays, and the seller would play me the new records on the other end. We’d both sit on the phone, and I’d listen to the records they played for me through a crappy telephone loudspeaker.

DH: You always had to decide how many records you wanted to order very quickly: I’ll take three, I’ll take five, I’ll take 20. Zack, zack. Then the next record was played for 30 seconds.

EI: I never heard the bass, just the distorted mids and highs. Those phone calls were helpful if you already knew an artist and hadn’t heard the new release yet, but I would only order a few copies of the records once I was totally sure—they had to pass the inhouse test first. And if they did, I’d order more.

DH: You couldn’t order enough of the important records, and you shouldn’t order too many of the other ones, because we couldn’t return any leftovers. That’s why Mark needed people who were well-versed in music. And DJ Rok certainly was. Like Mark, DJ Rok was a walking encyclopedia.

EI: Ordering records in big quantities was particularly fun. I remember the first time Tommi Gronlund from Sähkö Recordings came into the shop and cautiously asked if we might be interested in adding a few of his records to our assortment. I replied,“How about we take the whole pressing?”

DH: We were the first to notice new trends, since we heard everything first. Techno’s sound changed with Sähkö records. Then, everything became more minimal with Basic Channel. We made sure that we always had as many copies of these trend-setting records in stock as possible. This way, Hard Wax could set the trends.

EI: There was no cautious calculation, just great conviction. All the enthusiasm and passion of the Hard Wax team transferred to the clientele, and to the labels that dealt with us. Our regular customers included current Berghain residents like Marcel Dettmann, Fiedel, and Cassy. Many of them also worked with us for stints of time.

GB: Many artists who worked at Hard Wax would later become internationally successful: Marcel Dettmann, Shed, DJ Hell, Cassy, Achim Brandenburg, DJ Rok, Electric Indigo, and even me with Modeselektor.

EI: Many other international producers and DJs would pay a visit to Hard Wax when they were in Berlin – Robert Hood, Kevin Saunderson, Kelli Hand, Derrick May, Richie Hawtin, and later countless others, like Ricardo Villalobos and Mika Vainio. It seems like every DJ has been to Hard Wax at least once in their life.

DH: You would also see Daniel Miller, Afrika Bambaataa, or Jeff Mills in the store. Every Friday I would buy warm Bavarian Läberkäs sandwiches from a butcher nearby and bring them for the staff and a few of the DJs who hung out there. Warm Läberkäs and sweet mustard. Everyone loved that.

JM: Whenever I stayed at Mark’s place, I had this habit of going downstairs to Hard Wax and pretending that I was a customer. But in reality, I’d just hang out and watch the people – and what records they were buying.

DH: Hard Wax was formative for so many DJs. Even some of the Detroit DJs have said that Hard Wax had a profound influence on them. They discovered records from England or Berlin that they would have never found anywhere else.

JM: I was very surprised that they had a lot of material from the UK and a lot of house music from Chicago that I had never seen or even heard of.

ME: A typical day at Hard Wax: we opened at noon and were legally allowed to stay open until 6:30pm—Saturday 10am to 2pm—but in Kreuzberg no one minded that we always stayed open longer. After the day shift came the night shift, where we’d communicate with America and do our detective work. ELECTRIC INDIGO: I still remember the first time I walked into Hard Wax. It was in 1990, only a few days before the Love Parade, and a new UPS shipment was expected.

ME: The UPS person always came around 4pm, but the DJs would be there hanging out from noon onward. They didn’t want to miss anything.

GB: You didn’t have to stand in line if you were there early enough. Sometimes they had to hire a bouncer to let people in and out.

EI: That day, you could hardly move once you were inside. Tanith, Dr. Motte, and WestBam were some of the customers stocking up on new records, and they were in front of the counter. I was a newbie, so I was near the door at the other end of the room. But I could see DJ Rok—the most celebrated among the Hard Wax staff—unpacking the record boxes from where I was standing. He would pull a record from a box and rub it on his trousers so that the plastic casing could be torn open. Then he’d put the needle on the record and blast it through the sound system. And literally everyone wanted to buy that record. I felt like I was at the stock exchange. It was a total spectacle. Everyone in the room was hearing these new records for the very first time.

DH: There was a pecking order, a kind of right of first refusal. If WestBam didn’t want a record, someone else was allowed to get it—but not vice versa. DJ Rok was the only one who was allowed to secure the records that only had a single copy delivered. Or only one test pressing. Reorders could take weeks, sometimes even months. In the worst-case scenario, a record never showed up again—because only 100 were pressed in Detroit, and everything was sold out with the first shipment. But then again, a lot of stuff was never ordered at all. We were like the taste police. We didn’t order a lot of stuff that came from Frankfurt, or a lot of trance and house productions that we didn’t think were cool. Over time, we sold only what we thought was good. That’s how the Hard Wax school developed.

EI: And the DJs in the second and third row always got the good records one or two weeks after the very important DJs. But the times were dynamic: time and again, a DJ who nobody knew a month ago suddenly became very well respected. It was a totally hierarchical, but at the same time permeable, system.

GB: What was really great was when Jeff Mills, Mike Banks, or Richie Hawtin hung around at the store. For me, these people represent an attitude that defines a parallel universe to the music industry. And to experience them as real people was very moving.

EI: At Hard Wax, there have always been countless records on sale from what we call “author labels”—labels whose records are hand-stamped and numbered, run by artists or producers themselves. Over the decades, Hard Wax has also sold extremely limited, authentic records that were not available anywhere else. That really shaped the identity—for the crew, the scene, the DJs, and the record buyers.

JM: I have always been fascinated by the distribution world. And ever since I started Axis Records, I have experimented with music, as well as with distribution. For instance, I’d do a release of only 50 copies, exclusively for Hard Wax, and would ask the staff to give these records only to special people. I knew that the Hard Wax staff knew who they had to sell these records to. Planting 50 or 100 records exclusively at Hard Wax meant that all the international DJs who would pay a visit there would get this super-rare record, and they could include it in their sets. It’s like curating.

A record shop presorts, so that people can better find their way through the crazy jungle of releases. – Electric Indigo

SK: Everyone has their moment of cultural awakening. For me, it happened in 1993, while I was visiting a school friend whose older brother listened to techno records on vinyl. Listening to Aphex Twin, that’s when I got that first kick. The music floored me, as did the minimalist aesthetic of the record sleeves.

EI: The record sleeve is the international record shop aesthetic. These squares are displayed in the shop window and on every free square meter of wall space. And Mark Ernestus is aesthetically very precise. His design decisions have mostly shaped Hard Wax. He designed the logo and chose the materials to furnish the shop, giving it a rather industrial, cold touch—which merged wonderfully with the music being sold. This is especially true of the new shop.

MD: Hard Wax moved to Paul-Lincke-Ufer in 1996. The new store was just a few blocks away from the old one, but much closer to the U-Bahn station. The interior design was basically carried over, but whereas everything had been cramped in Reichenberger Strasse and every square centimeter used for storage space, the new Hard Wax was spacious.

ME: It was a big relief, even though it was sad to leave the “hallowed halls” behind us. We now had an entire factory loft of 350 square meters. The front went to Hard Wax with two and a half times the original space, and Moritz von Oswald and I moved into the back half with Basic Channel’s office and studio – and Dubplates & Mastering, which we had started after buying the vinyl cutting lathe a year before the move. That had developed into its own business and needed more space and administrative effort.

EI: Mark always wore workwear by Carhartt, from Detroit, which was the fashion equivalent of the functional, no-nonsense design that characterized the new factory floor. The predominant colors were all shades of beige and gray, sometimes deviating into olive green or anthracite. This understated expression also perfectly matched the innovative music Mark and Moritz made as Basic Channel.

DH: Basic Channel’s sound was based on Mark and Moritz’s enthusiasm for dub music from Jamaica. But it was much more minimal. I remember how Jürgen Laarmann, from Frontpage, once asked me, “What’s the next hit?” I played Basic Channel for him, and he said, “Are you kidding me? Nothing happens on this track!” When Basic Channel entered the scene, hard techno was still all the rage.

JM: But I wasn’t surprised that Mark had initiated Basic Channel with Moritz von Oswald. Before techno, Moritz was part of Palais Schaumburg. Mark and Moritz were very close at the time. Why shouldn’t they start a music project together?

DH: It was a holistic thing. There was the record store, the studio, the label, the mastering studio, and a dubplate machine. As Basic Channel, Mark Ernestus and Moritz von Oswald represented a new chapter in the Berlin techno scene. They released records under various project names, often with Tikiman on vocals: Basic Channel, Rhythm & Sound, Maurizio, Quadrant, Phylyps, et al.

GB: Basic Channel’s music seems to be from a timeless dimension. Even though some of these tracks are 30 years old now, they still sound like they’re from today. If you put on Maurizio’s “4.5”—there’s nothing left to say. Everything’s there. Formulating itself in this music is a pure, repetitive, relaxed spirit of techno—which wants nothing and everything at once. It’s absolutely transcendent. And it was a real phenomenon. Thankfully, someone kept pressing the “record” button.

DH: There was no need to collect dub techno records from anyone else. Mark and Moritz single-handedly shaped and defined the genre with their releases. All the others were just copycats. To this day, you can play a stunning set exclusively with stuff from Basic Channel. And the groundbreaking and innovative quality of their music permanently reflected on the outstanding reputation of the store.

JM: And don’t forget: they had a dubplate machine at Dubplates & Mastering. That was incredible. You could have your own exclusive dubplates cut there.

DH: Like WestBam, Jeff Mills, and countless others, I had my own dubplates cut there. Sometimes I would record tracks from Ron Hardy on cassette, remaster them at home, and then have them cut as my own dubplate. I always included four or five tracks from exclusive dubplates in my sets. That way I knew I had records nobody else owned. But getting these dubplates wasn’t cheap—it cost five times as much as a standard vinyl maxi-single. And you had to handle these objects of desire with the utmost caution, since the material, which is softer than vinyl, wears away quickly. You can play a dubplate maybe 100 times, but you have to keep turning up the volume and the treble, because the playback quality decreases over time.

ME: At first, the machine was in a room next to Moritz’s studio in Berlin-Steglitz, but the building was going to be torn down, and we thought it was time to bring everything under one roof. Around the same time [that] the store moved, business changed, too. US imports became less important for us, partly because a number of new distributors had emerged from the techno scene and were now competing in US imports. What also became more important to us was Basic Channel with its sublabels, as well as the other labels that emerged around us and are strongly associated with Hard Wax—Soundhack, MMM, Errorsmith, Wax, T++, Sleeparchive, and many more. These are producer labels with a radically independent approach that focuses on music, and not on all the crap around it. They refuse to abide by the laws of the market and promotion, and are confident that quality will prevail. Their stamped white label records sometimes sell larger quantities than big record labels with their own promotion and graphics departments. It’s very rewarding to be able to provide the infrastructure for something like this and be a platform where determination is appreciated by the audience.

EI: What made the shop on Paul-Lincke-Ufer different was that it was hidden. You couldn’t stop on the streets and look into the shop window anymore. You had to walk through a courtyard to a backyard, and then up stone stairs to the fourth floor.

SK: At the new address, Hard Wax perfected its archival system for electronic music, which follows a code. You needed that system because the majority of the records had barely distinguishable sleeves. Once you understand the code, you can find every record you’re looking for. And thanks to that presentation system, Hard Wax was for record collectors what a library is for readers and—a place where you could lose yourself.

GB: Before I started selling records there in 2000, I’d make a pilgrimage every week. As time went by, I began to understand the system of how to buy records as a DJ so that you could establish your own style. At Hard Wax, I learned that you had to know a little bit about the labels to get the tunes you were looking for.

MD: Many customers felt intimidated the first time they entered the store—including me. If you asked the “wrong” question or requested a record that wasn’t cool, the Hard Wax staff might treat you like you were invisible.

SK: The sorting by label gives the selection a gravitas and seriousness that impresses many of the customers. Since many artists release on numerous labels, you have to look for the same artist under various monikers, spread throughout the store. But the way the records are sorted contains a profound understanding of how electronic music is produced.

GB: Hard Wax always rejected trends. It was more about timelessness. Good techno has something timeless about it. One of the peculiarities of techno is that, as a genre, it can’t really reinvent itself. [That aspect takes] place in the nuances, in the differentiations and reinterpretations—but always within the framework of techno. There’s something almost scientific about it.

EI: Nowadays you don’t necessarily have to play vinyl records. Many DJs, including me, spin records digitally. That’s why Hard Wax developed an extremely well-curated download store on its website. Record shops have always been filters and navigation aids. A record shop presorts, so that people can better find their way through the crazy jungle of releases. This is important today, since everyone can put their tracks online and more music is being released worldwide than ever before.

SK: For some, the high-resolution digital download is the only real way to buy and play electronic music today—no obstacles, no wear and tear, no vinyl stands in the way of pure sound. Others strictly reject downloads and swear by vinyl as the only true medium. But during the 90s, vinyl was the only way to own a track and play it in a club. I am not surprised that Hard Wax still exists. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that, apart from the relocation in 1996, Hard Wax never focused on growth. It’s more about representing a certain type of electronic music as authentically and comprehensibly as possible. Just because a store has more music and more things on offer doesn’t necessarily make it better.

ME: More than 30 years later, I still struggle to put into words what I love about house music. The simplicity, rawness, determination, and reduction of means; the DIY approach; the will to self-determination—which, however, does not express itself in an aggressive manner, but in one that’s playful, experimental, funky, soulful, or uplifting—to this day I can’t even avoid the clichés.

Credits

- Text: Max Dax

- Photography: Christian Werner

Related Content

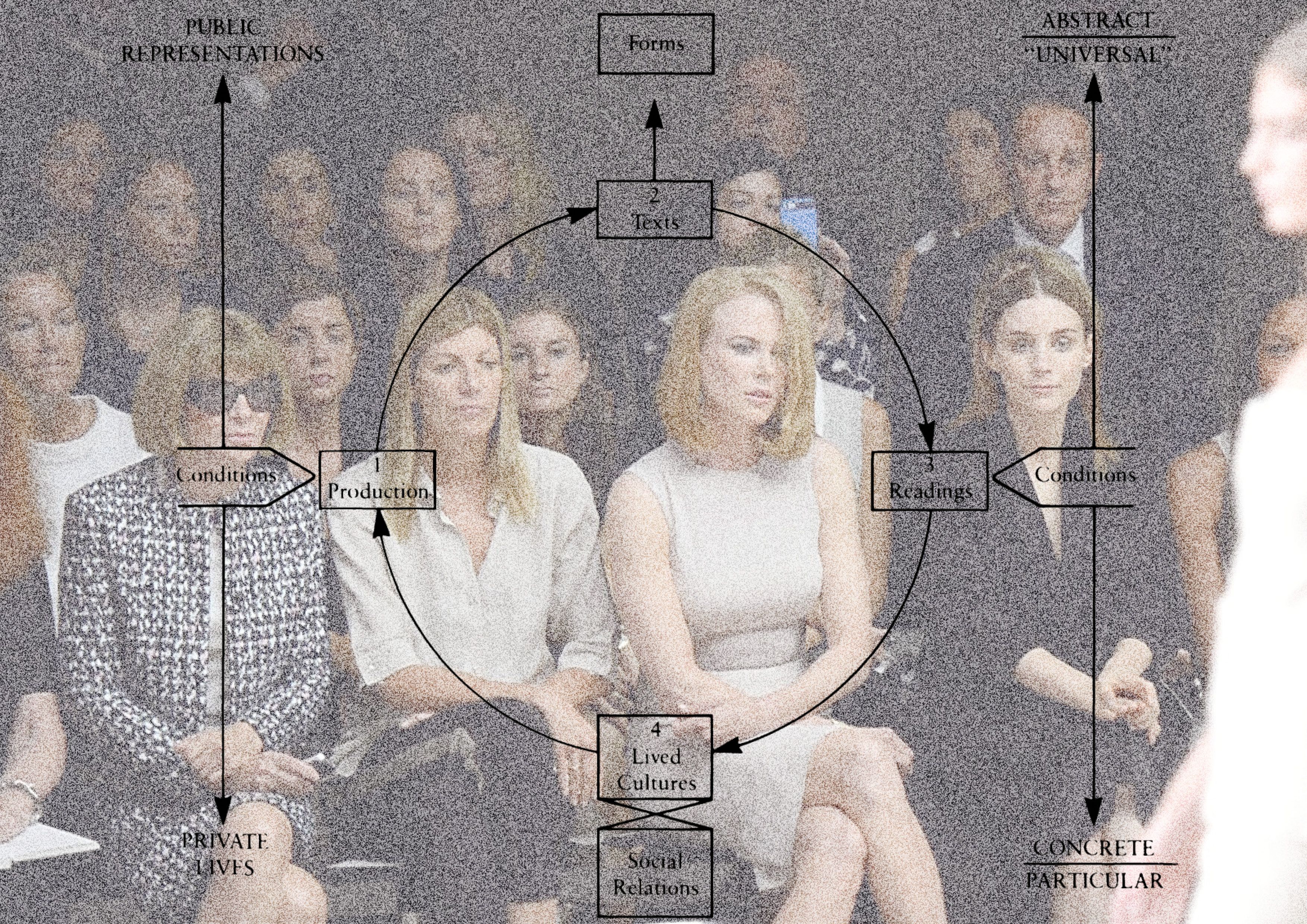

Runway Music: Musicology for Clothes

“If this is hell then I’m lucky.” In the Eye of the Storm, Listening to DJ SCREW

BTS: BILLIE EILISH WORLD TOUR 2022

RAVE: Before Streetwear There Was Clubwear

RBMA Co-Founder Many Ameri on Two Decades of Musical Exchange

Inside RISIKO Issue 2: A Fanzine about KRAUTROCK

Lust & Sound: Man About Town MARK REEDER’s Forgotten 80s Berlin

“Slowed & Throwed”: Exhibiting DJ SCREW