Who Wants to Be a Human Jukebox? Richie Hawtin

|SHANE ANDERSON

It wasn’t Richie Hawtin’s plan to become a musician.

As a young, skinny nerd from LaSalle, Ontario, he was into “electronic gizmos and computers” and thought that he would pursue a career in special effects for movies. Luckily for the world, he “fell into” nearby Detroit’s club culture in the early 1990s and started to perform sets that have since seduced millions of people over the past 30 plus years.

Hawtin is not only a minimal techno DJ legend, however. In some circles, he is as equally influential for the acid-drenched dreamscapes he has produced under the name Plastikman, a moniker that has many admirers that extend beyond the hardcore minimal techno scene. Recently, for instance, Raf Simons used Plastikman’s “Kriket” from 1994 in the Prada Men Spring/Summer 2025 show—which wasn’t the first time that Hawtin scored a Prada show. The collaboration between Simons and Hawtin began in 2021 when the brand enlisted Plastikman to compose a series of runway soundtracks and it has continued with their global event partnership and series entitled “Prada Extends,” which debuted at the Tate Modern’s live art and performance space and has travelled to Tokyo, Miami, and Thailand. With a lot to look back on, Shane Anderson spoke to Hawtin about his work with Prada, as well as about his storied career, his new tour that touched down at Sónar, and the magic of being present.

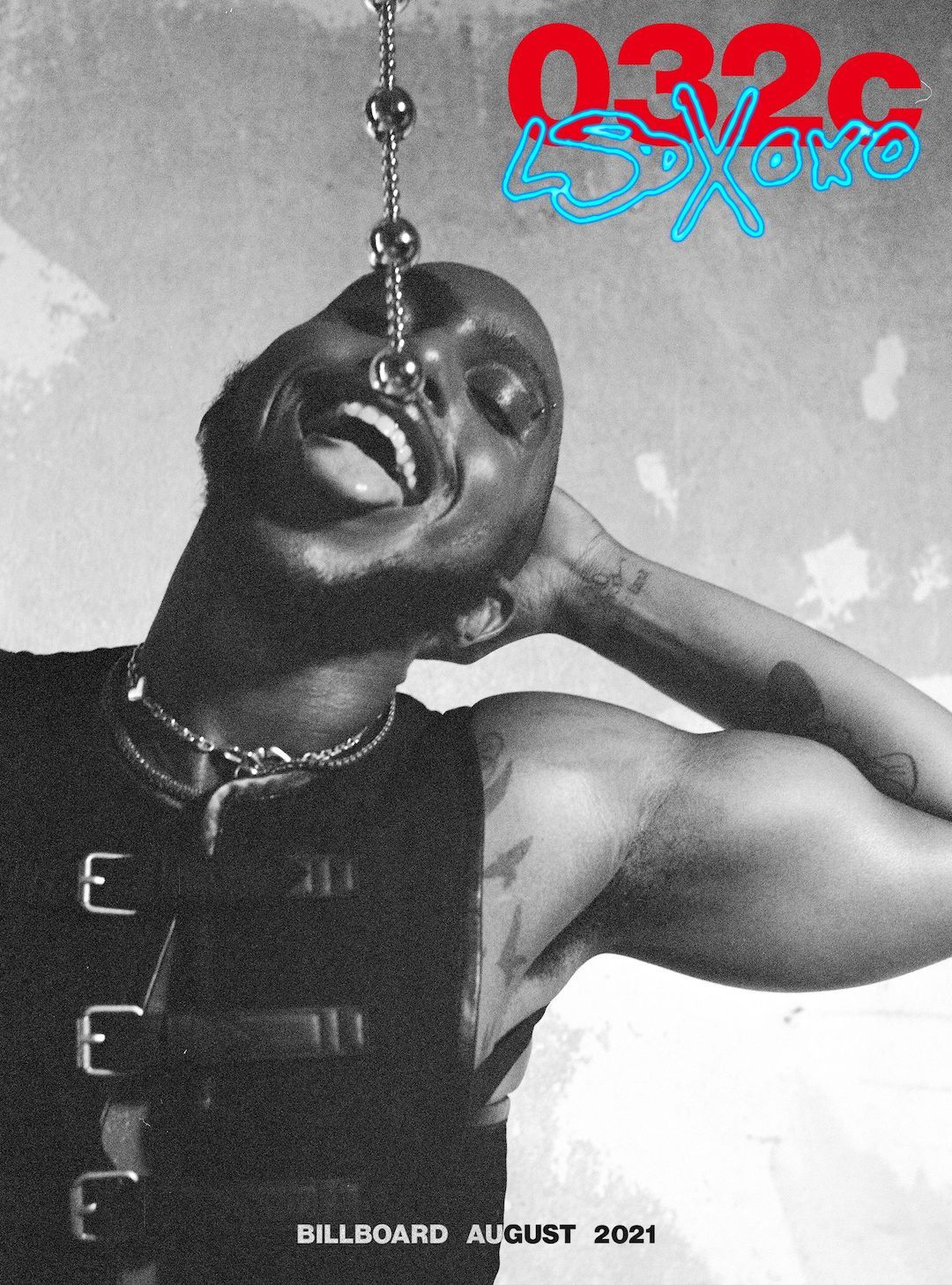

SHANE ANDERSON: First of all, it’s a great honor to speak to you. I’ve been listening to your Mixmag live! recording for almost 30 years.

RICHIE HAWTIN: That particular CD was a big deal since it helped solidify the momentum that I was building in the early 90s. Mixmag was one of the only magazines dedicated to electronic dance music at the time and having the cover and making the mix was a huge thing for me.

SA: It has aged like a fine wine [laughs].

RH: Thank you. I think my generation was really lucky to be in that first or second wave of techno and electronic music, which was still a very new form of music back then. Our intention was to create futuristic and sci-fi sound, which is why I think it has aged well. In some ways, we’re living in that future now. But let’s see how it ages over the next 30 or 40 years.

SA: You’ve had such a long career as a DJ and producer. What keeps you going?

RH: I’m probably trying to keep the dream of the past alive. And not just for myself. I’m trying to instill the ethos of what drove the music in those early days in others. That sense of futurism, of looking beyond the present or the immediate future, has been somewhat lost now. What also keeps me going is that I still get goosebumps when I hear a great record. And I get goosebumps when I’m playing because I know something magical is happening. That feeling of living in the moment with everybody that’s there and being on the edge where neither you nor the audience knows what’s going to happen next is what life is about.

SA: What you’re saying suggests that you’re a very open and porous person.

RH: Definitely. I would say I’m very sensitive to my surroundings. I think you need that when you’re DJing. You’re listening to the crowd and navigating people’s emotions with the music; you’re navigating the world and taking the temperature. This openness is how I make music but it’s also how I try to lead my life and run my businesses. In some ways, things are more planned nowadays. It’s more difficult to have happy accidents. And these events are truly what makes life meaningful.

SA: But the flipside of that is that sometimes it doesn’t work. Sometimes you fail. What do you do when that happens? Surely there are sets that go horribly wrong.

RH: Definitely. There are multiple sets that were, at the time, the worst possible set I’ve ever done in my life. And they’re with you from the beginning until the end, both in memory and in their consistency to surprise you and turn up again and again. It still happens, where you ask yourself: “How could I not navigate the crowd tonight? I’ve been doing this for 30 years!”

SA: Does one stick out?

RH: I have to be a bit careful. There’s this mandate in today’s age that you should put yourself out there on social media, that you should be authentic, but if you’re truthful and natural, nobody actually wants to hear you. And besides, my perspective on a bad gig might be totally different than somebody else’s.

But I will say this: I came from clubs and very small parties at the beginning of my career. And when I started doing raves with 5,000 or 10,000 people, I really struggled. If I found myself in a hole, I couldn’t pull myself out. I would just go deeper and deeper into the hole and the bad set would get worse and worse, which would totally destroy me. Over the years, I found a way to do those events. I became very good at noticing when something is going wrong and when I’m having a bad time. I can now consciously find a positive way out—I have certain records labelled “pop” or “easy” in my crate and I don’t play them often but sometimes I will and hopefully they get me back on track to the music I would normally play.

SA: I saw your sónar set, which is part of your DEX EFX XOX tour. What’s the idea behind it?

RH: In the late 90s, I was pretty progressive with my use of tech in the DJ booth. I had drum machines and quickly moved from regular turntables to digital turntables and used effects where I added delays and reverb. So, I had a show back then that was DEX EFX 909—909 being for the Roland TR-909 drum machine. This new show is a continuation of that, where the XOX is a very nerdy way to talk about all the Roland equipment—303, 909, 101, and 808. Basically, it’s DEX, the music I play on the turntables, EFX, the effects I put on top, and XOX, the extra synths and drum machines that I create during the show.

SA: So, this involves a lot of improvisation.

RH: It’s heavy on improv, yes. And that even applies to the tracks I play. When I’m preparing a show, I listen to around 20,000 or 30,000 tracks in a year that I usually whittle down to about one or two percent. I might then end up with 100 or 200 tracks that are tagged with little words that remind me of the songs in my digital crate. I usually have one or two tracks for the beginning and/or the end but everything that happens in between is spontaneous.

This is the fundamental magic of DJing: the spontaneity of reading a crowd and putting on the right record at the right moment. And even though the art of DJing is much more popular today, I don’t think that the value is fully understood by the crowds or even all the DJs. We’ve become so playlisted. I get it. Sometimes you need to make a Vegas show—and you know, unless you’re a jam band, even most live sets are scripted. But at the heart of DJing is being as spontaneous as possible. It’s like I said earlier about taking the temperature of the room and deciding to take a new direction. It’s about trusting yourself and standing behind your decisions.

The same goes for producing tracks or making recordings of live sets. It might be that one set has a couple of fuck ups because things weren’t planned but then if you’ve done the set ten times and it’s immaculate, it might not have the same feeling. I believe that if it’s too perfect, too scripted, then you start only hearing the machines and you’re just a jukebox. And who wants to be a human jukebox?

SA: Techno has become so codified. How do you keep it from becoming a museum piece?

RH: You know, it never feels like it has become too codified or like it’s a museum piece to me. There’s always something new coming into the mix when I listen to those 20,000 new tracks. And the same goes for the equipment. It changes every two or three years too.

Things are completely different than the early days where there wasn’t as much electronic being made. Things have become much more disposable. Some say it was better before, but I don’t know. I will say that I go through tracks quicker and the first couple of sets after I get the new batch are always better. It’s when the stream is flowing, new things are coming. If something feels boring or historically repetitive, I decide to listen to the next track and then another. It’s my job to find a way to excite myself, to get my hair standing on end, so that the people on the other side of the dance floor or those listening at home can feel my excitement. If you’re in club culture and playing for people that are half your age and you don’t have any enthusiasm, any excitement, then you can forget it. You’re a goner.

SA: You mentioned listening to scores of tracks. What’s your listening routine? Do you sit down Monday morning with a cup of coffee and dig in?

RH: I wish I did. You know, I’ve tried to have that schedule for 30 years and it never works. My trusted system for about 20 years—or since Dropbox has been around—is to have somebody download the tracks and put them into a Dropbox that syncs with my computer. Whenever I have the time, I open my computer and look at all the newest music that’s been sent to me. Then, I jump onto a digital store and buy some things. It’s very random. When I do get into it, I always have like two to four hours of just listening, but there’s no set time or rhythm. I do a lot of it on the go. Nowadays, you can be in a café listening to music on a great pair of headphones and you don’t need big speakers. When I’m at home, I have a little one I want to spend time with, and I also want to be in the studio.

SA: Are you still making music under the name Plastikman?

RH: I haven’t done that much recently but it’s something I’m actively working on bringing back next year. I did do a Plastikman test last year, where I was investigating some lighting. Somebody introduced me to a light called a Photon, which is so beautiful, and so I created a show for the ICRAM series at the Centre Pompidou experimental sound laboratory that was just me and one of these Photon lights. I want to explore this some more.

DJing took over my creative life at some point. I had a lot of fun doing it. It took me around the world. But I’m heading towards a place where I would like to do less and go deeper and deeper into things. What I’m interested in is: How can you reduce things and find the perfect amount of ingredients? Where you walk into a gallery or have a great conversation or see a good movie, and where all the pieces come together.

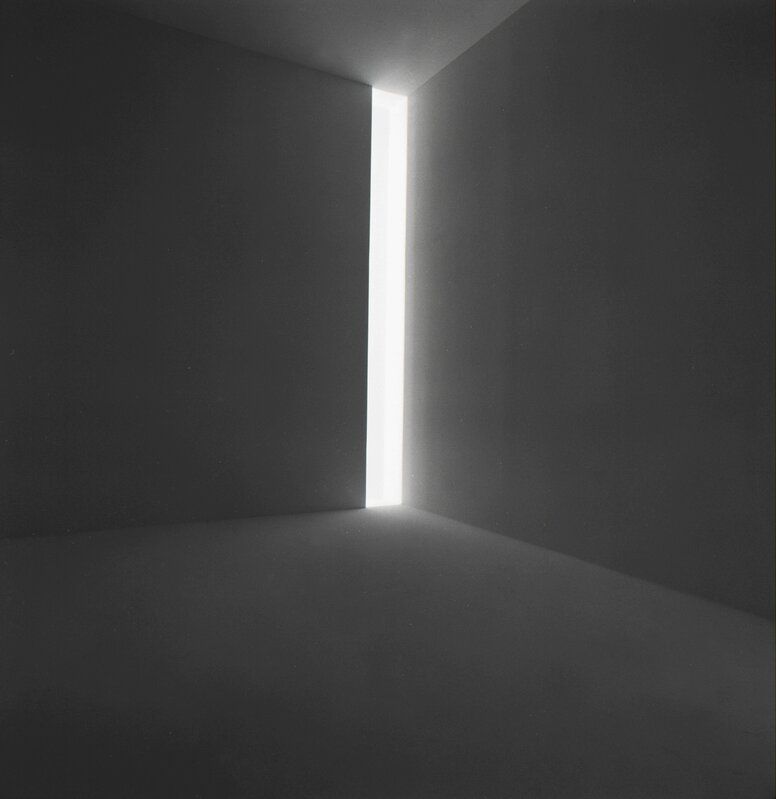

In the world of creativity right now, everything has to have a narrative. It’s almost like the narrative is more important than what the work is. But I think that the experiential works of losing yourself in the lights and the music on the dance floor has a lot of power. I don’t normally say, this, but I think it has a lot of healing power. It brings people together. It unites them. Not everything has to be political. Not everything has to have a message that needs to be driven into everybody’s skulls. And that’s the cultural world we live in right now. I come from the school of James Turrell, Mark Rothko, and Anish Kapoor, and not of the Jeff Koons school or any other. All of them are valid. I just resonate with the one although I know there are a lot of people who resonate with the others.

SA: Another project you’ve been involved in is the education program CNTRL, where you toured college campuses and gave lectures on music, technology, and the history of parties. So, you could say, you’re interested in experiential projects and historical ones, right?

RH: I think it’s part of my responsibility. The genre has such a rich history and there aren’t that many people who were around back then who talk about it. For me, it’s about bringing back some of those original values and letting people know what I saw back then. Education is about passing on experiences. I’m also working with [the company] Erica Synths on these bullfrog synthesizers for curriculum in classrooms and I’m mentoring three up-and-coming artists who are trying to get into electronic music. I also have a project in Portugal, where I live, that I hope to develop over the next three to five years. It will be a small, intimate studio retreat. Artists can hopefully come in and share ideas in the studio and have conversations. I’m excited about it but I’m not there yet. I’m moving some of the chess pieces around to get there though.

SA: It sounds like you’re involved in a lot of projects outside of just DJing.

RH: Yeah. And in the last couple of years, I’ve also been really busy with making music for Prada, which has been a really challenging and inspiring project. I’ve been good friends with Raf Simons for many years and I’ve been very lucky that every once in a while, he has a project and will call me up. I always jump at the opportunity when Raf calls me because I know he’s a fan of my music. That means his ask is coming from the right place. And it’s usually something that challenges how I think or how I create music.

SA: It’s interesting because making music for a fashion show feels like there wouldn’t be much room for improvisation, which seems to be so important to you.

RH: 100 percent. But the question is: how do you have a moment of fashion, of looking at a beautiful piece on your screen or in front of you while having music or a soundtrack that connects you to that live performance? Because it’s a live fashion walk, right? Even when it’s scripted. And so, it’s that contrast that begs me to explore it.

SA: One thing I’ve picked up on in this conversation is that you’re nostalgic for the ethos of club culture but that you’re not necessarily nostalgic about the music.

RH: Yes, it’s about some of the ideals that attracted me to this culture. Part of the futurism I previously mentioned was the idea that tomorrow is going to be better. And we all felt that on the dance floor, dancing towards tomorrow. I can be quite disparaging about how some of them are missing or disappearing, which is what drives me and other educators around the world to teach and pass down some of that knowledge so people can make their own decisions about whether those values fit in today’s world.

SA: It’s hard to believe in a better future today.

RH: It’s definitely more bleak. And aside from the ecological problems, I wonder if it’s because of social media. It just feels like everyone wants to be like everybody else instead of trusting their instinct. Going against the grain just doesn’t seem to be cool.

SA: How do we break out of that?

RH: I think the problem has to do with technology. Although we think we’re in control of it, it’s more like we’re being controlled. And I’m not talking about Big Brother. I mean we’re being controlled in how we’re consuming things every day. Here’s an example. I remember being in Miami and was at this restaurant that had this amazing melting chocolate dessert. And in no time at all, everyone had it on their menus. Everyone’s just playing catch up and following everyone else. Originality is lost in the process. We need a new balance. We need more organic relationships and finding ways for us to believe in ourselves. People need to take more chances. People need to get back in the driver’s seat with their experiences and not just be controlled by an algorithm. And if we do, we’ll once again become a society that enjoys differences and not just one that homogenizes everything.

Credits

- Text: SHANE ANDERSON