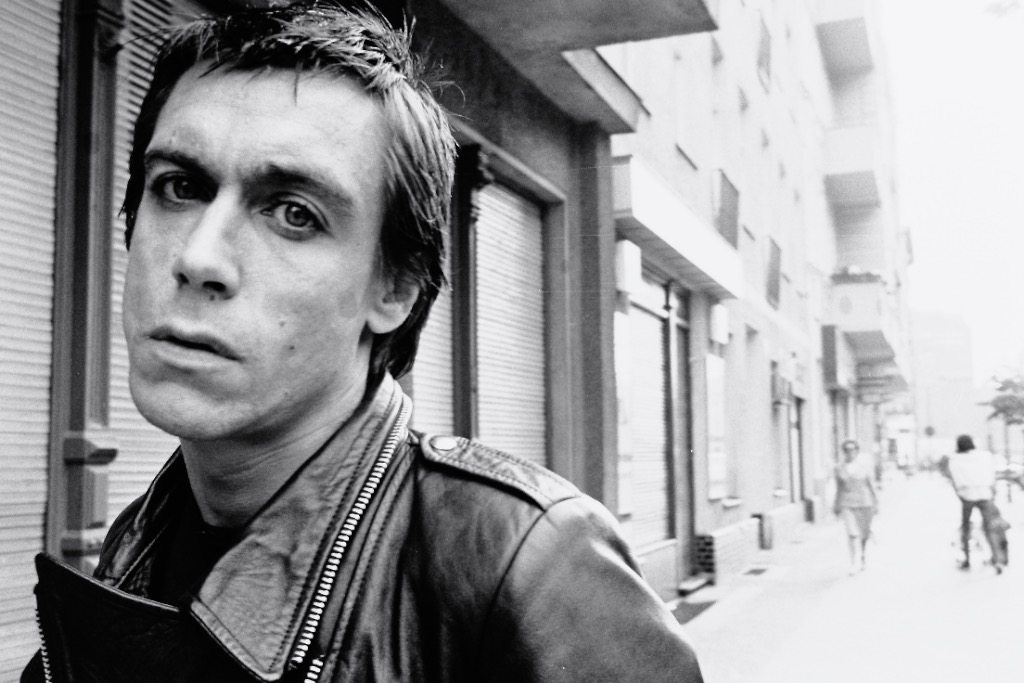

Lust & Sound: Man About Town MARK REEDER’s Forgotten 80s Berlin

When Manchester native MARK REEDER arrived in West Berlin in 1978, his first order of business was to make a unannounced visit to the pioneering German electronic musician Edgar Froese.

Froese didn’t come to the door, but Reeder nevertheless managed to embed himself in Berlin’s underground music scene over the course of the next twenty years. With a penchant for wearing outdated German uniforms and a wide reaching group of friends and collaborators, Reeder became an immediately recognizable figure west of the wall and was instrumental in shaping the city’s music culture in the 1980s. Reeder’s adventures are now chronicled in B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West-Berlin, a new documentary film which debuted at last year’s Berlinale and is now in theatrical release. Making use of an extraordinary archive of rarely seen footage culled from Reeder’s own archives, the film is an intensely personal account of a city “in a state of emergency,” as Reeder puts it. 032c sat down with Reeder to discuss the film and his memories of the city.

DARRYL NATALE: How did this film come about?

MARK REEDER: I wasn’t involved initially. It started as a conversation between Jörg Hoppe and Heiko Lange, the directors. Heiko’s got kids and he was saying that they had no idea about what was going on in West Berlin before the fall of the wall. So Jörg had the idea of making a documentary about West Berlin. He has a long history in music television, and was the manager of the Neue Deutsche Welle band Extrabreit in the 1980s. Initially the idea was to be a traditional talking head style documentary, but there was no red thread to tie it all together.

How did you get involved?

Jörg approached me about mixing the sound and restoring the tracks for the film and when he told me more about the project, I offered to lend him my VHS tapes from the 80s in case there was something of use to them. It was mostly TV programs I’d made and general footage I accumulated over the years. A lot of it I hadn’t even seen myself. I didn’t feel the need to re-watch them and embarrass myself. So he took them home with him and two days later he phoned me up and said “What have you just given me? I’ve never seen any of this material.” And probably nobody else had either. Even the television programs were aired only once. That was the policy in the 80s. But after Jörg saw the tapes, he completely revamped his idea and asked if he could base the film around my life in Berlin.

In my research there were a lot of references to footage and TV programs which turn up nothing in Google.

A lot of it was lost. Even The Tube Berlin special was lost. And The Tube was the popular TV show in the 80s. It launched a lot of bands. This was the program which started Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s career with their infamous performance. But when it came to the point when we wanted to license the footage for the film, Grenada TV opened the box where the footage was supposed to be stored and it was empty. So even the popular programs were difficult to track down, not to mention the more obscure programs.

But you had a copy?

I had one, which we used for the rough cut, but there were all these film reel numbers and time codes. So I went back to the cassettes and wrote down everything I had and sent it to Grenada. In the meantime they’d released a DVD box set of the best of The Tube, but unfortunately the Berlin special was never included because they didn’t know where the first reel was and couldn’t be bothered to track it down. Finally after months they were able to find it. They must have just gotten someone to troll through the archive and look in every single box.

The portrait of Berlin painted by the film centers primarily around the experimental music scene. Was there anything else that you wish you could have included?

Loads. There are things I’d have loved to include but we didn’t have any footage. For example the Metropol, the gay disco at Nollendorfplatz. Nobody ever filmed in there for one reason or another. People didn’t want to go dancing with their camera, so there’s no footage. The cameras were so heavy, it was like carrying three bags of sugar around with you. I couldn’t be bothered lugging it around.

That was a parallel scene to this new wave avant-garde scene I was involved in. Everyone I met in the Risiko Bar, where Nick Cave and Blixa Bargeld used to hang out, they would only stay in that scene and listen to a certain kind of music. They never would have dreamt of going to the Metropol for a Saturday night.

But you were involved in both scenes.

I’m a versatile person. I don’t like to pick just one thing. To have a diverse evening of culture, to go to a punk rock concert at SO36 and then have a few drinks at Dschungel and then go to the Metropol and dance the night away and then finish it with a nightcap at the Risiko. That was the diversity of my nights. But if I told the people at the Risiko that I was going to the Metropol, they’d all groan. They didn’t know what they were missing. When Bernard Sumner came to Berlin after Ian Curtis’ death, it was one of the first places I took him. I told him “If you stay in that Manchester scene, you’re just going to sound like a second hand Joy Division.” So I took him to the Metropol so he could hear this music at a phenomenally loud, pulsing volume. And it had such a big influence on him. It was because of this music that New Order started becoming a more electronic driven band.

What were they playing at Metropol?

Hi-NRG, underground, disco, François Kevorkian type stuff. Not the cheesy Studio 54 disco, more like Paradise Garage. It became cheesier later when Westbam took over the decks. He was a bit more pop, and he was younger too, like 19. Chris, the original DJ at the Metropol, he only liked to play the deepest, darkest, most obscure hell disco. I don’t even know if you can call it disco. It was underground dance music, very trippy. That was the kind of music I was into. It was just a really interesting experience being at this club. It was the biggest gay disco in Europe, and all my friends who went to the Risiko or Dschungel never went there.

Berlin’s music history has been dominated by electronic music since the fall of the wall. Are the two related?

The decay of the avant-garde music scene had already started earlier. It had already started to fall in on itself around 1984. The city was changing. The attitude was changing. In the early part of the 80s, bands like Malaria! or Einstürzende Neubauten were looking towards making their own form of expression. They were trying to do their own thing. It was underground, totally non-conformist and unconventional and had an anarchic, destructive side. It was art music. On the other end of the scale you had the mainstream German New Wave acts like Nena and Falco. But around 1984, things started to merge. The Squatter scene started to become heavy rock. It started sounding more like Linkin Park than Einstürzende Neubauten. The direction started to get lost. I could see it happening, but I wasn’t that bothered. I always had my refuge in the Metropol, in the Hi-NRG sound. And as for the Geniale Dilletanten, the group of artists who had been the avant-grade force in Berlin, they were trying to professionalize in the hopes of getting gigs in foreign countries. But as they got more professional, it started sounding bland.

Which undermines the idea of the dilettante.

That’s the thing with dilettantism. It’s very quickly out the window.