All Nighter With Dalston Jazz Bar

|ALMA LEANDRA

Dalston Jazz Bar is a hazy little joint right off London’s Dalston High Street. Its 62-year-old owner, head chef, and DJ, Robert Beckford spends hours over hot pans filled with fresh prawns, salmon, or the catch of the day, then takes over the decks after the dinner service. The club/restaurant hosts two sets of dinner services each evening, accompanied by a live jazz band that plays within arm’s reach of your table. The music intentionally dominates the conversational frequencies, a tongue in cheek comment on our society’s inability to sit together in “silence.”

The restaurant has received acclaim for its top-notch seafood, which is served on a donation basis following a “pay what you think it’s worth” policy (with a base donation of 20 Pounds). At 10pm, the tables are stripped and the place transforms into a club, where Beckford curates music consisting solely of protest songs.

Having decided to follow him for a day, I was buckled in a bright orange Ford Cortina MK3 along with Beckford, his son Duke Uibel, and my assistant, as we headed towards the Billingsgate fish market on a Wednesday. The license checking staff threw a smirk at our car before ushering us through. It’s safe to say that this was the only old-timer in the entire market. Beckford’s average Wednesday consists of handpicking fish and making deals with tradesmen from 2am till 5am, then rolling on until 1am the next Thursday. The next day, we sat down to chat in the secondhand clothing store that he opened across from his jazz bar.

ALMA LEANDRA: What led you to establish a jazz bar that offers food?

ROBERT BECKFORD: I never planned to open a jazz bar. It started when a friend said I would be the right person to run a bar. I decided to check out the property and was pleasantly surprised. The place had been boarded up for years, which would be unheard of in any other area in London. In Dalston you have Turkish and Indian communities known for their business acumen. So, when a Black guy is asked to take over a business, there’s a problem. For the first six months, I paid very low rent without any plans and used the place to have drinks with friends. Passersby began asking if we were open. I’d reply, “Yes, but also not.” You could come in, have a drink, but could you buy it? Yes and no, because we couldn’t tell if they were police officers. So, we adopted the policy of “pay what you think it’s worth,” which attracted attention, police included. They demanded I apply for a late license. After receiving that, we operated as a club till 2am.

AL: How did your restaurant’s menu shift from bar food to seafood?

RB: People wanted snacks, so we sold bread rolls. They demanded more and I decided to sell crocodile, zebra, camel, and shark—the weirdest animal meats possible. People started to ring up the council complaining that we were selling illegal wild African food. The more they did it, the more I searched out obscure meats. Then the pandemic hit, and we were forced to pivot into a restaurant model and sold seafood only. There was no way I could run it alone at that point, and that’s when I asked my son to come on. To get really good chefs in London, you have to pay them astronomical amounts of money, and even when you do, they have to move on to further their careers. So, I taught my son how to prepare the food, and now we’re co-running the bar.

AL: What made you introduce the jazz performances and you spinning the decks after hours?

RB: Although the bar made lots of money, it became incredibly boring. So, I decided to transform the bar into a cultural space. I wanted it to be more interactive. So, I introduced live jazz bands during the dinner service. If you go to the bars around the corner, like Ronnie Scott’s or the Vortex, it’s like listening to jazz in an orchestra. It’s very solemn. The music lacks life. With the club, most of the DJs were playing music in a playlist manner, whereas if you look at Jamaican DJs, they communicate and interact. So, I started doing that and it was a success.

AL: One thing I particularly enjoyed is that the music is so loud during the dinner service that you’re not always able to talk. As a society, we have unlearned how to sit in silence and enjoy each other’s presence. It was refreshing.

RB: I’m glad you picked that up. The idea of playing music is that you don’t sit down and talk. I’m inviting you to a big party and allowing you to engage with each other. That’s why we have the menus “standardized.” The bottom line is: one plate serves two, meaning you share. The music played is shared too by not just listening to it as background music and concentrating only on the food. I believe this is how you’re supposed to be dining. They asked Marco Pierre White, the chef who taught Gordon Ramsay, what the best meal he ever had was, and his response was, “There’s no such thing as the greatest meal, it’s the greatest people I have sat with.” And that’s exactly what I’m creating.

AL: How do you select your musicians?

RB: You get all these young up-and-coming musicians who are just out of posh colleges, and they all play jazz—or so they say. They play well but there tends to be no soul, no feeling. Occasionally, you do find the good ones, you give them a trial, and then they will play. I pay them x amount of money to find musicians to play with them.

AL: So, you have them running the selection for you and trust them?

RB: I trust them. I used to try to recruit my own musicians, but it became too much hassle—running around, making phone calls. There’s a vast jazz community, but like any family, they have their feuds. They will refuse to play with certain drummers or bassists. Even when everyone is on stage, some musicians hog the spotlight or come in late on purpose. I’ve had to intervene in physical fights mid-performance, all while the audience remains blissfully unaware. It’s like dealing with a bunch of squabbling kids sometimes. I’ve heard that orchestra players are even worse. Somebody told me that if a person playing in the orchestra is coming to listen to music, they’re coming to see how many mistakes you’ve made.

AL: Jazz, unlike many other music forms, can be improvisation friendly and not necessarily bound by rhythm or beat. Is this fluidity something that you personally feel close to?

RB: Jazz is storytelling. The beat, which comes from Africa, is completely different from what it was in the 1940s and 1950s. What I liked about jazz or swing music was the rhythm and beat, it had a way of crying and singing. It’s not something that you just listen to, it’s what you bring to the music itself. Take the opera, if you don’t know the story, you can’t go to the opera and then understand the story. Sometimes you have to understand and then consume. In jazz, you need to have that soul that brings “the jazz out of you.” It’s the same with the beat of reggae. Certain beats now bore the hell out of me because I lack the relationship to them. They miss that ethnicity—I don’t like using that word, but they lack that African soul that jazz from the 1960s brings out of you.

AL: What inspired you to be on the decks yourself?

RB: Lots of DJs would come in but the people who came to the bar never came back. Back at university, I loved that student music organizations played for everybody. So, I decided to do just that. I played for everyone, and people began returning.

AL: In a prior interview, you mention Gillett Square, which your bar is located on, and the prominent violence on it. Does the socio-political environment of the square affect your bar negatively?

RB: It’s a violent area. The square has become a hub for individuals grappling with alcoholism as well as social and mental health issues, leading to lots of violence. That square is still there because it’s all about containment. Over my 24 years here, I’ve experienced 15 burglaries and six physical assaults due to alcohol, drug use, prostitution, and mainly, dealers wanting to sell in my bar. Once you establish that you don’t entertain that, they leave you alone though.

AL: What is the curation guideline of your music selection?

RB: I keep on having arguments with guests on my music choice. Let’s say I’m playing Italian or Turkish music; their respective peoples will complain: “Those are only generic tracks to each culture.” I know that. I have to do that because how else do you engage people who are not from those cultures? Obscure music can get lost in translation for a non-niche crowd. Because if I play reggae and don’t play Bob Marley, I’m automatically isolating certain people. To this day, I have discussions with people that fail to grasp the political underpinnings. Take Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldiers.” I ask guests if they know what it’s about, and they say, “It’s just nice music.” No. You do realize it’s about slavery? Their response is that I’m too political. Bob Dylan, Lily Allen, or Sinead O’Connor—their music is all protest music. People are becoming subconsciously animated to expressing themselves without necessarily recognizing it. I charge and encourage them. With some music in here, I have people breaking down and crying. Sometimes, they go to the bar and drink more, so occasionally the music gets tampered down a notch. That’s when guests feel animated to ask for song requests, which I don’t do. They don’t always realize there’s a theme.

AL: Do you bring your heritage to the jazz bar?

RB: I wouldn’t claim to bring my heritage. I’m Jamaican, and we are supposed to eat in a communal way. The Jamaicans who came to England in the 50s, like my parents, were influenced by their working-class jobs and different timings of arriving at home. This led to a more hierarchical dining style, with fathers often not joining the family at the table. I found it disheartening. People don’t understand if you didn’t look at the Black community on a Friday, Saturday, and especially Sunday, you wouldn’t see them eating together much. At university, I was shocked to see how they did things. Eating from tins and partying in clubs with bright lights, blaring music, and getting totally pissed. I quite liked this [chuckles]. I’m telling you now, most Black people think I’m crazy when they come to the jazz bar.

AL: Yesterday we met at 2am to head to the Billingsgate fish market for your fresh seafood purchase. How do the seafood trade hierarchies complicate things?

RB: We used to arrive at 4am. What we didn’t realize is that at that time you got the last choice of the fish. But in order to go in before 4am you have to get a special certificate which can only be issued by someone trading for at least six months. If you’re from Manchester, like me, and you don’t have any connection, then the question is: How can I get into the market at 2am? You can’t. So, the only thing you could do is go in as a “walk in” and buy it at a higher consumer price. They’re archaic rules. These traders who have been in the business for generations stroll around with stacks of cash, paying upfront and disappearing with their goods. They’re unbelievably wealthy. One thing you notice too is that there are around two women working there. The language, racism, and sexism—they don’t care, they are in their own world. And complaining to them is pointless; if you do, you risk losing access to their goods.

AL: Do you believe in manifestation, as in telling yourself what you desire?

RB: No, I don’t tell myself. I know, it sounds cocky and arrogant. It was the fact that I refused to be poor. That’s my problem. There are three things that guide me: I refuse to be poor, to have a boss, and I get bored very easily.

AL: What is one thing the businessman in you regrets?

RB: I just wished I’d have done this in Berlin when I had a chance. I could have done it.

Credits

- Text: ALMA LEANDRA

- Video: ALMA LEANDRA

- Video Assistant: NICOLAS THIEMANN

Related Content

Setting Horses On Fire with Jordan Hemingway

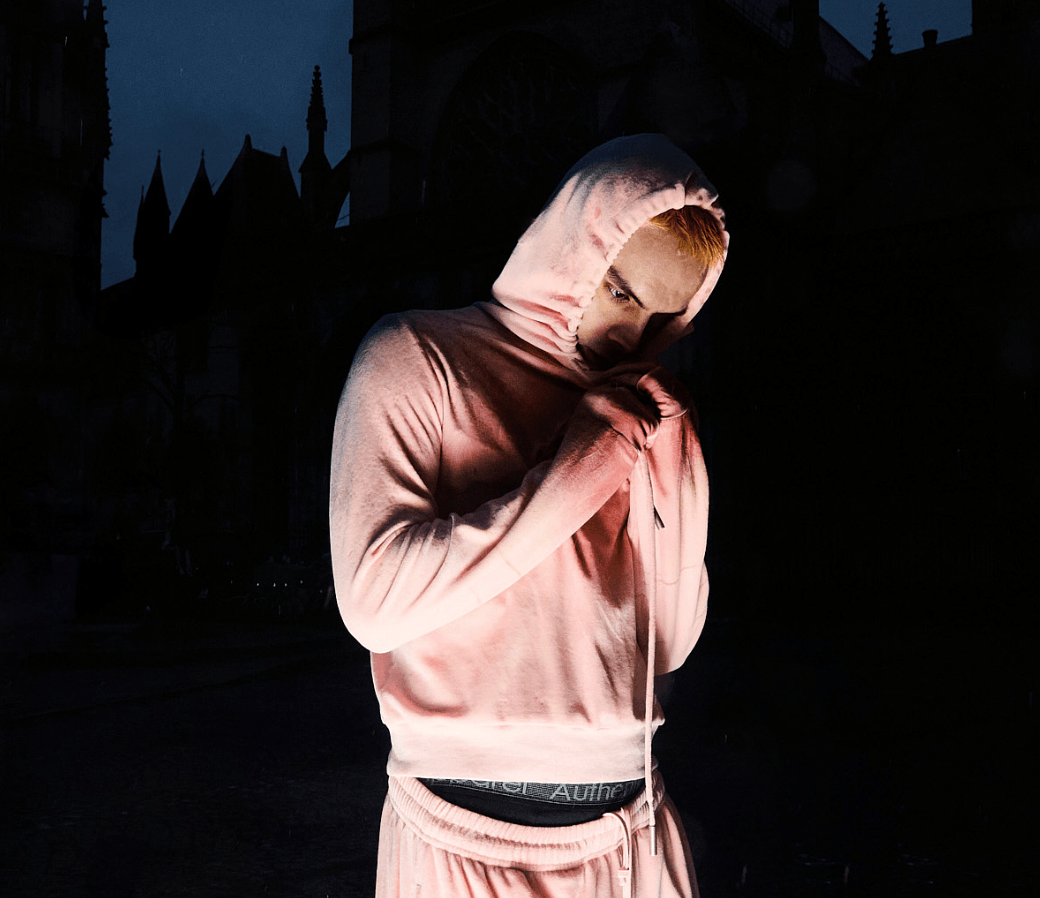

Thoughts on Ekkstacy in Berlin

DOECHII on Swamp Rap, Alter Egos and Narcissistic Exes

032c Guest List - Makko

Gated Nightmares: Herrensauna’s Cem Dukkha

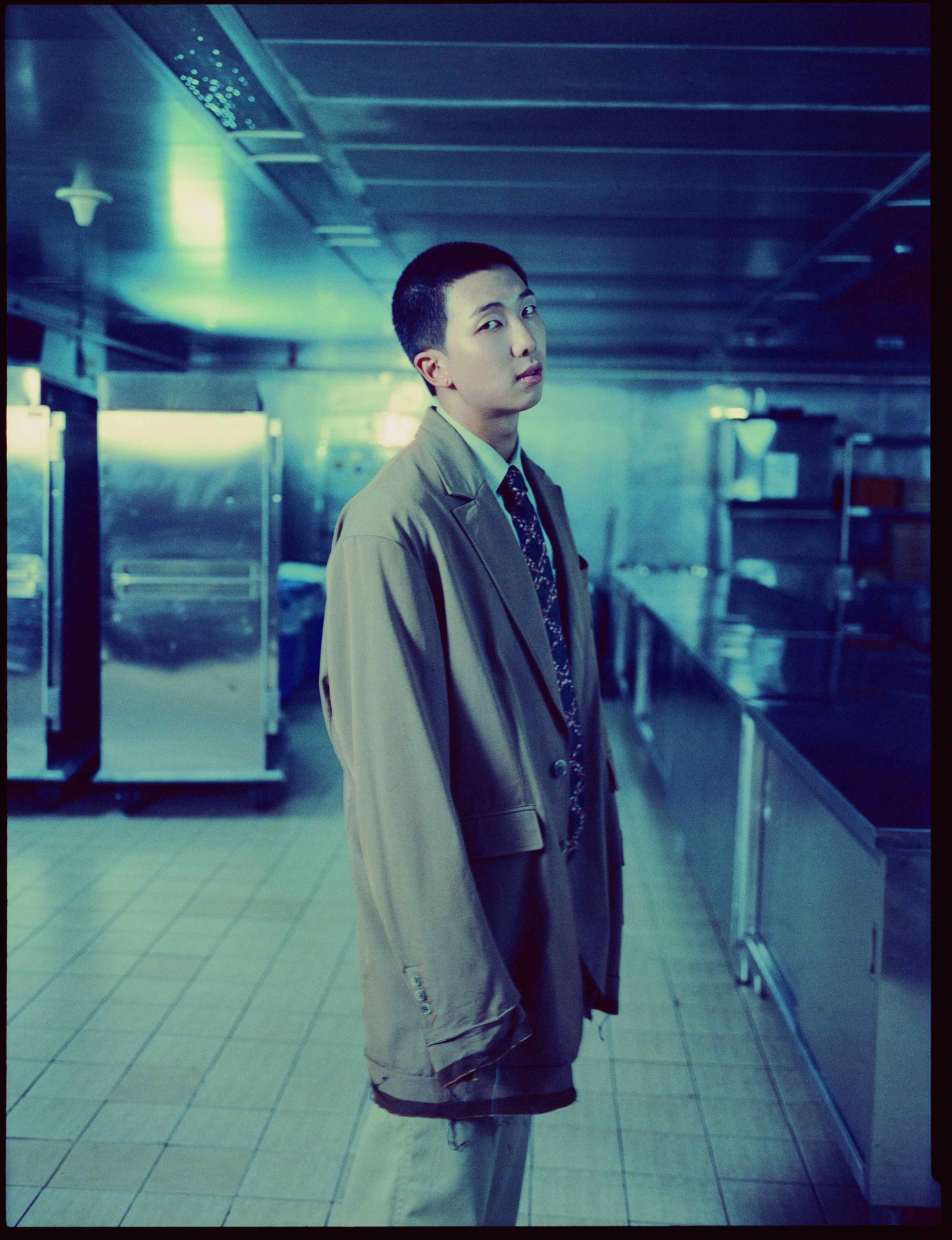

Learning From Antiquity: RM of BTS

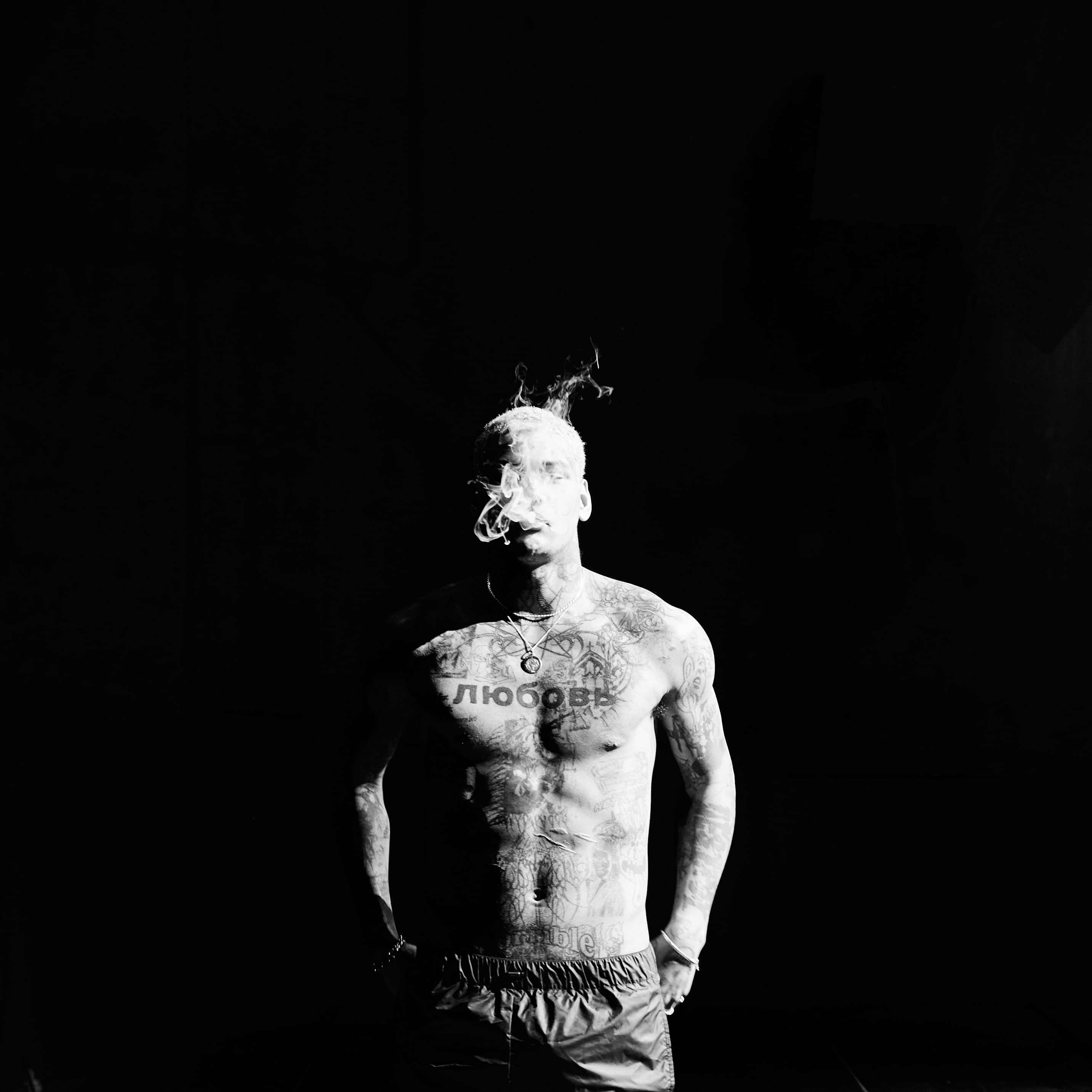

A Bad Night’s Sleep with Sega Bodega

Sevdaliza Questions Human Authenticity

The Art Institution of the Future

The Dare Knows What's Wrong with New York

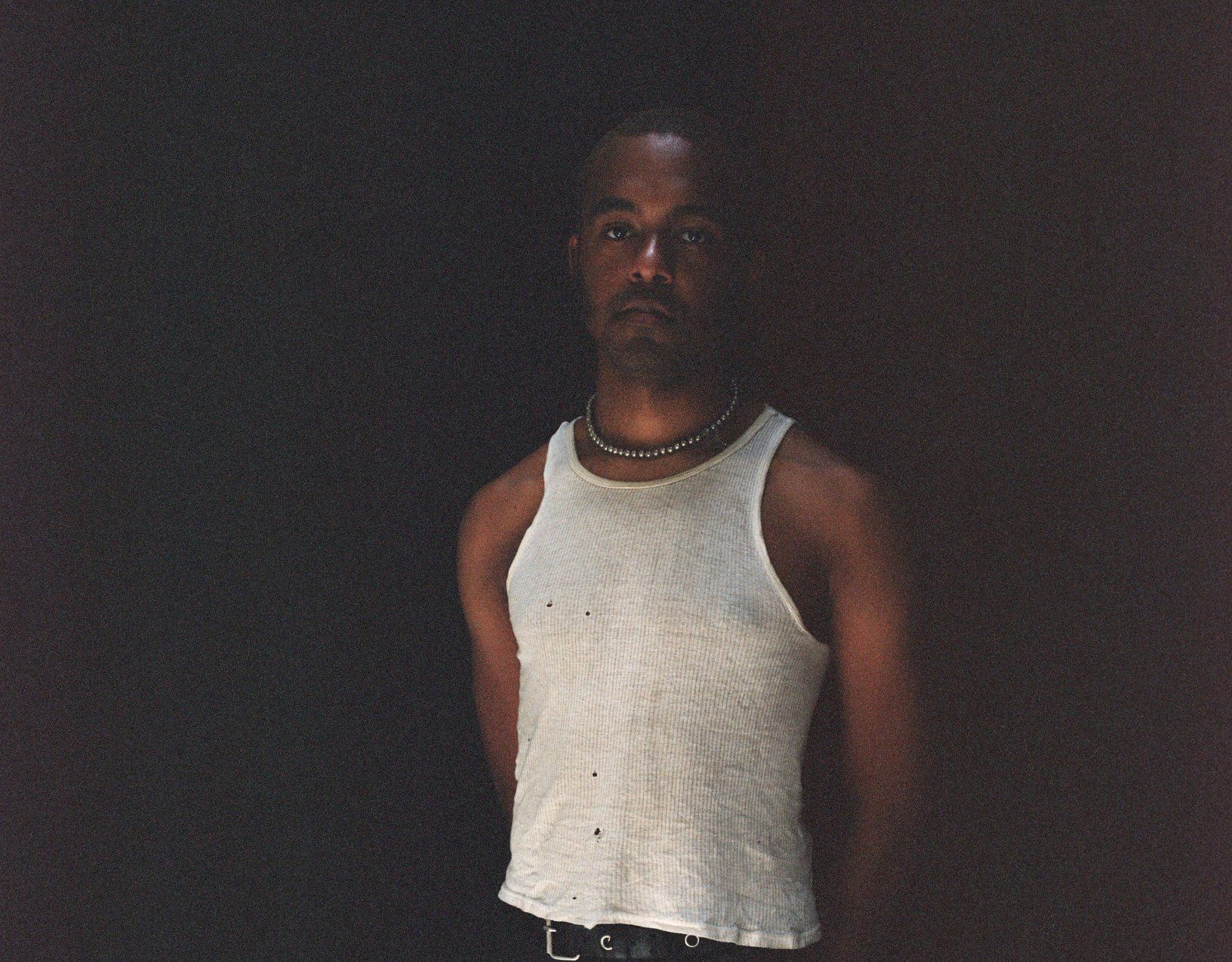

An Exorcism of a Prior Identity: Jasper Marsalis (Slauson Malone 1)

Sonic Fictions and Alternative Histories: Kode9