The Dare Knows What's Wrong with New York

|CASSIDY GEORGE

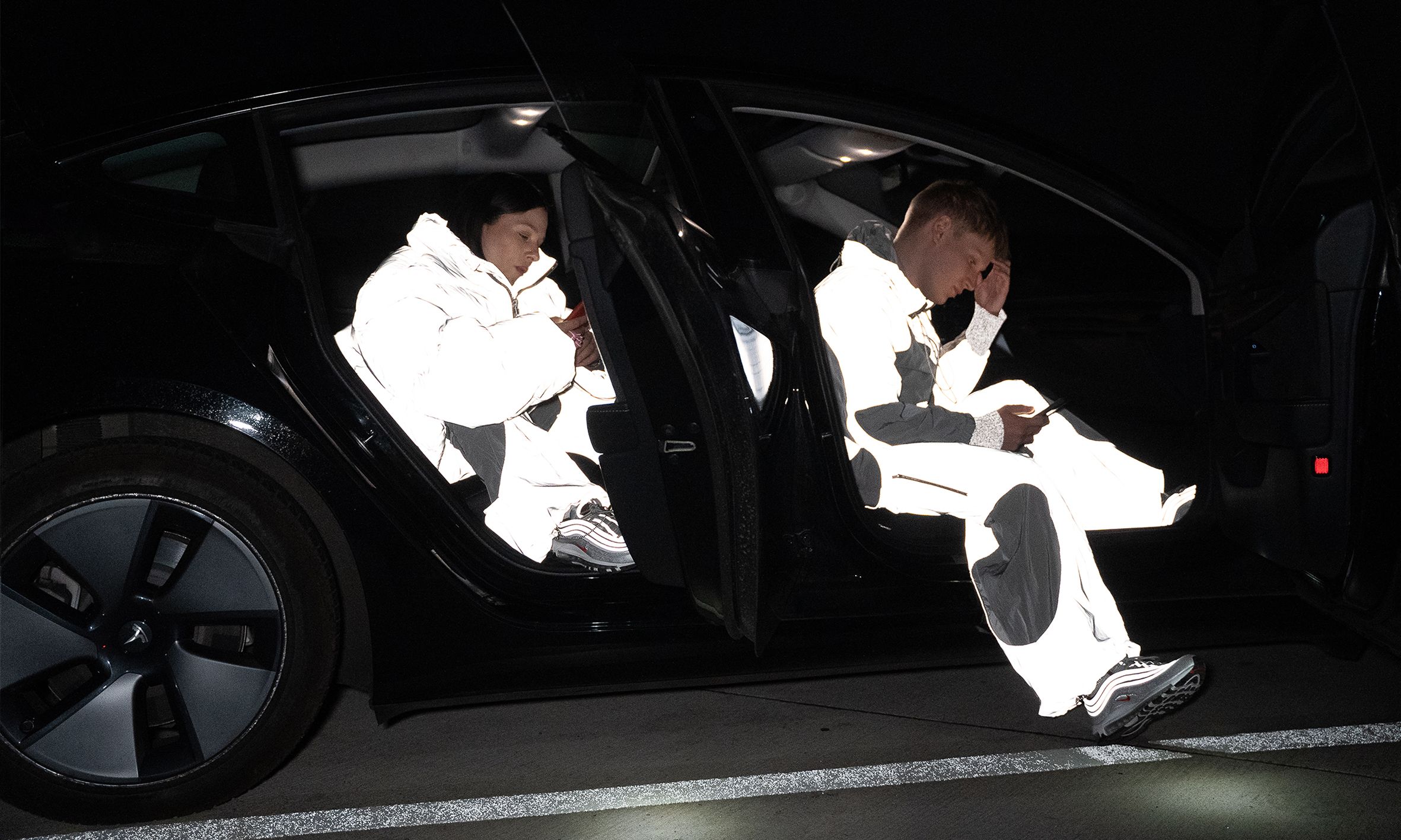

If you looked at a photo of New York musician Harrison Smith or listened to the music he makes under the name The Dare without any further context, you might assume that Smith is British. Not only because his physical appearance recalls various British rock icons, but also because his sonic imprint is best described with a word that is indispensable in British English, and chronically underused (and underappreciated) by Americans: “cheeky.” Smith has spent the last few years fighting for the relevance and value of cheekiness—which Merriam-Webster defines as “showing a lack of respect or politeness in a way that is amusing or appealing”—in both New York nightlife and a burgeoning corner of pop music that writers have dubbed an “electroclash revival.”

At some point in the late 2010s, the higher-ups in the music industry seemingly decided that “authenticity” was an artist’s most valuable currency. Authenticity’s position on the attribute totem pole was elevated due, in part, to the resounding success of acts like Billie Eilish and Pheobe Bridgers, who made moody, confessional music for people who gaze listlessly out of windows with tears streaming down their faces. But being held prisoner by a global pandemic triggered a need for a different kind of catharsis. Afterwards, music fans no longer wanted to hear echoes of their pain. They needed to go out, make out, and feel less for a change.

Smith spent years making thoughtful, electro-indie rock under the name Turtlenecked, but to little avail. As is the case with many hit records, Smith wrote the horny, post-woke banger “Girls”—a song in which he details an exhaustive list of the kinds of girls he likes—effortlessly, in jest, and with almost no genuine intentions of releasing it. “It even feels strange that I wrote it,” he told GQ, describing an out-of-body and out-of-character experience that helped him identify and name his new musical animus: The Dare. Perpetually clad in his signature Gucci suit, Smith transformed into a caricature of a womanizing, sleazy scenester—and satiated a yearning for the return of the character. With crass lyrics that hit like a mid-coital face slap and production that unabashedly embodies Y2K dance-rock acts like LCD Soundsystem, The Rapture, Fischerspooner, and Peaches, “Girls” and the EP and record that followed have allowed people to relinquish their pent-up, feral energy with joy.

Within the past two years, Smith’s once desolate DJ nights at Home Sweet Home in lower Manhattan transformed into the sold-out party series, Freakquencies—where attendees wearing outfits that could easily have been purchased at Urban Outfitters in 2007 get to cosplay as Myspace-era it-people at a Misshapes party. While already a regular on the fashion circuit and a certified muse of Hedi Slimane (he played the afterparty for Slimane’s Celine show “Age of Indieness”), “Brat Summer” catapulted Smith into yet another tier of fame. The more familiar you are with The Dare, the more obvious it becomes that he created Charli XCX’s hit song, “Guess”—which sonically mimics the infectious refrain on Daft Punk’s “Technologic” and lyrically fixates on a pair of women’s underwear. “I really believe Harrison will be one of the next big pop producers,” Charli XCX told the New York Times. “Give him five years. He’ll have had his fingerprints over many big albums.”

But the best indications of Smith’s relevance in the pop cultural canon are not his glowing profiles, they’re his dismissive Pitchfork reviews, which were penned by Ivy League graduates. The Dare isn’t for the pretentious in the same way that Brat isn’t for the “demure”––and that’s precisely the point of Smith’s project. By now, his many critics should understand how the internet works: the louder that the arbiters of good taste whine and complain, the more powerful Smith becomes.

CASSIDY GEORGE: Many people now know you for producing Charli XCX’s summer anthem “Guess,” but you also played at her infamous Boiler Room in Ibiza this summer. I can’t imagine anywhere more opposite to Home Sweet Home than Amnesia. What was that experience like for you?

HARRISON SMITH: So many people were like: “What is this guy doing in a suit?” I’ve worn it all over Europe and America, but Ibiza is by far the most extreme and inappropriate place to wear a suit. Even just walking through the airport in Ibiza felt like stepping into an alternate universe. For example, in the Milan airport, all of the advertisements and billboards are fashion related. That’s how they say: “We’re the fashion city.” But because nightlife is the economy in Ibiza, there are just massive advertisements with lineups and giant pictures of DJs like Dom Dolla. If you look closely, you can see him in the background of the Boiler Room for a second. I was playing and felt someone tap me on the shoulder, and then turned around and saw a moustache and trucker hat and was like, “It’s you motherfucker!”

Everyone who played was kind of nervous before the set because we didn’t know what the vibe was going to be like. I was going back and forth over possibilities in my mind until the actual moment of the set. Even right before I walked into the club, I was asking myself if I should be playing Balearic classics. I had no idea what people wanted to hear. As soon as we got there, it became clear that we should all just do whatever we do best—and have fun. Because I played last, I was like, “Oh boy, I really gotta send it.” So I prepared a playlist of songs for maximum detonation effect.

CG: I laughed out loud when you played “Firebreak” by Confidence Man. Since then, I’ve been trying to figure out why that track feels so funny and familiar. Do you know where the sample is from?

HS: It kind of sounds like “Meet Her at the Love Parade”—but also like Vengaboys and a lot of other 90s crossover dance tracks. It reminds me of the kinds of songs you would hear growing up in gym class. That was probably the first time I ever heard “Pump Up the Jam.” I think Confidence Man and I share a love of humor and fun, kind of above all else. They make music that goes hard and that is really fun to dance to, but it also gives you pause and lets you laugh. I don’t think a lot of other dance music aspires to do the same thing emotionally.

CG: You studied English Lit in college––what was the motivation behind that decision?

HS: It’s funny you ask because I spent all day yesterday trying to remember the name of my freshman year English professor––and it only just now popped into my head. It was sort of inspired by her. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do when I got to college. I originally thought I would study music but I wasn’t very impressed with the curriculum. It was structured more for academic music, not pop music or “real life” music. I wanted to major in something classic and was more interested in the language arts than in anything else. It felt the most fitting––and I’m really glad I did it. I use it every day!

Learning how to write creatively helps me with my music. I studied a lot of poetry in college and that’s what I wrote my thesis on. I think you have to read a ton and write a ton of bad stuff before you’re able to write something good. Even though my music is stupid to a lot of people, it’s very intentional. And it takes a long time to be able to write something intentionally...but in a good way.

CG: What did you write your thesis on? Do you have any favorite poets or writers?

HS: My thesis was about the use of music in the poem “Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats. But the Romantic poets are not my favorites, I’m bigger on twentieth century poets. I reference Anne Sexton on the last song on my album. There’s a New York poet named Frederick Seidel that I’m obsessed with, who also influenced my album a lot. Lately, I’ve been reading this Rene Ricard poetry collection––his work was kind of forgotten about but then rediscovered by living writers, and now has a lot of retrospective appreciation.

Henry Miller is very influential to me. I like a lot of these really masculine writers, but the ones that are a little more unhinged. I’m not that interested in Hemingway or Fitzgerald, for example. I think Bukowski is funny. He and David Foster Wallace are thought of as having a very “meme-y” perception—or as being very “memeable”—by the general public, but when you get down to brass tacks, the writing is insane.

CG: A parallel poetry scene appears to also be blossoming downtown right now—specifically a sexy, smutty strain of poetry. I’m thinking of Matt Starr and Dream Baby Press. Are you involved in that world?

HS: I know all of those people well. I love Matt Starr’s poetry! I saw him do a reading at a house show not long ago where everyone was drunk and screaming, and he was just screaming the poems over them. Forever magazine publishes a lot of cool stuff, and we recently did a pop-up together. There’s also Heavy Traffic magazine, and Dean Kissick has this thing called Earth. There are a ton of writers bopping around and rubbing elbows with musicians right now. It’s a really good time to be in New York.

CG: I lived in New York between 2013 and 2017 and nightlife was completely unexciting to me. There was an interesting psych-rock scene in Brooklyn, but everything beyond that felt phony or forced. It seemed like everyone who was my age in New York at that time was trying to chase or recreate what it felt like to be in New York decades prior. Is COVID what ultimately reinjected that magic and excitement into nightlife in lower Manhattan?

HS: I got to New York in 2018 and was making music. I was out every night at shows, but it was very much during the tail end of this DIY Brooklyn scene and attitude. Until after the pandemic, there was never this much excitement around nightlife or even music. Things just changed. It was really easy to get people to go out post-lockdown, and it had been a long time since there was any kind of club culture in New York, outside of the die-hard people and places that always keep it going. Things aligned and people became very excited about partying, dancing, and living in the real world.

But it’s not like all of this just happened magically. I was DJing at Home Sweet Home every Thursday for two years straight. In the beginning, I was playing on Monday nights and the only people there were me and two friends. I would play whatever I wanted, and I barely even knew how to DJ at the time. I just learned through repetition. When I moved to Thursdays, it became easier to convince people to come and it eventually turned into a bigger event. While I was doing that, there started to be more of an interest across the US and Europe in extroverted music that’s more theatrical and that has this sense of play. Parallel scenes developed in London and LA. Even in Paris, there are a few people who also have this wacky take on dance music and club life in general.

CG: Is tying yourself so overtly to a city a double-edged sword? When you become a fixture of a scene, does that limit or inhibit you in any capacity? Can you ever leave New York?

HS: I feel like I’ve already left the scene and that it’s time for something else. I travelled so much in the last year. I can no longer even throw my party at Home Sweet Home, due to capacity restrictions. However, I am still very attached and very much around.

CG: Earlier this month, you released the album What’s Wrong with New York. What is the intended tone? Is it a defensive, as in: “Well, what’s so bad about New York?” Or is it declarative, as in: “This is what’s wrong with New York”?

HS: I wanted it to be a little bit provocative, but also completely ambiguous. I want to let people make up their minds about it, instead of telling them outright what I think. But I will say that a lot of The Dare is about doing stuff in real life. There are a few lyrics on this album that reference this post-Covid, real-world push. The Dare is like a call to action.

The title summarizes this weird real world versus internet dichotomy, in terms of attitude and creativity. In real life, there are a lot of great musicians making things in Manhattan and Brooklyn—and there’s a lot of interest from the music industry. It generally just feels like a very exciting time to be in New York. And yet, on the internet, people have the exact opposite take and have the worst things to say about anyone with any degree of notoriety. Everything gets flattened into this Dimes Square straw man. The same people who are like, “This place is terrible!” online typically live in Brooklyn and don’t even go [to Dimes Square]. People on the internet who are outside of everything are angry and just don’t get it. And it’s kind of cool.

CG: “It’s cool” was not the conclusion I anticipated.

HS: Well, it’s cool because if you’re living in the real world, everything is great.

Credits

- TEXT: CASSIDY GEORGE