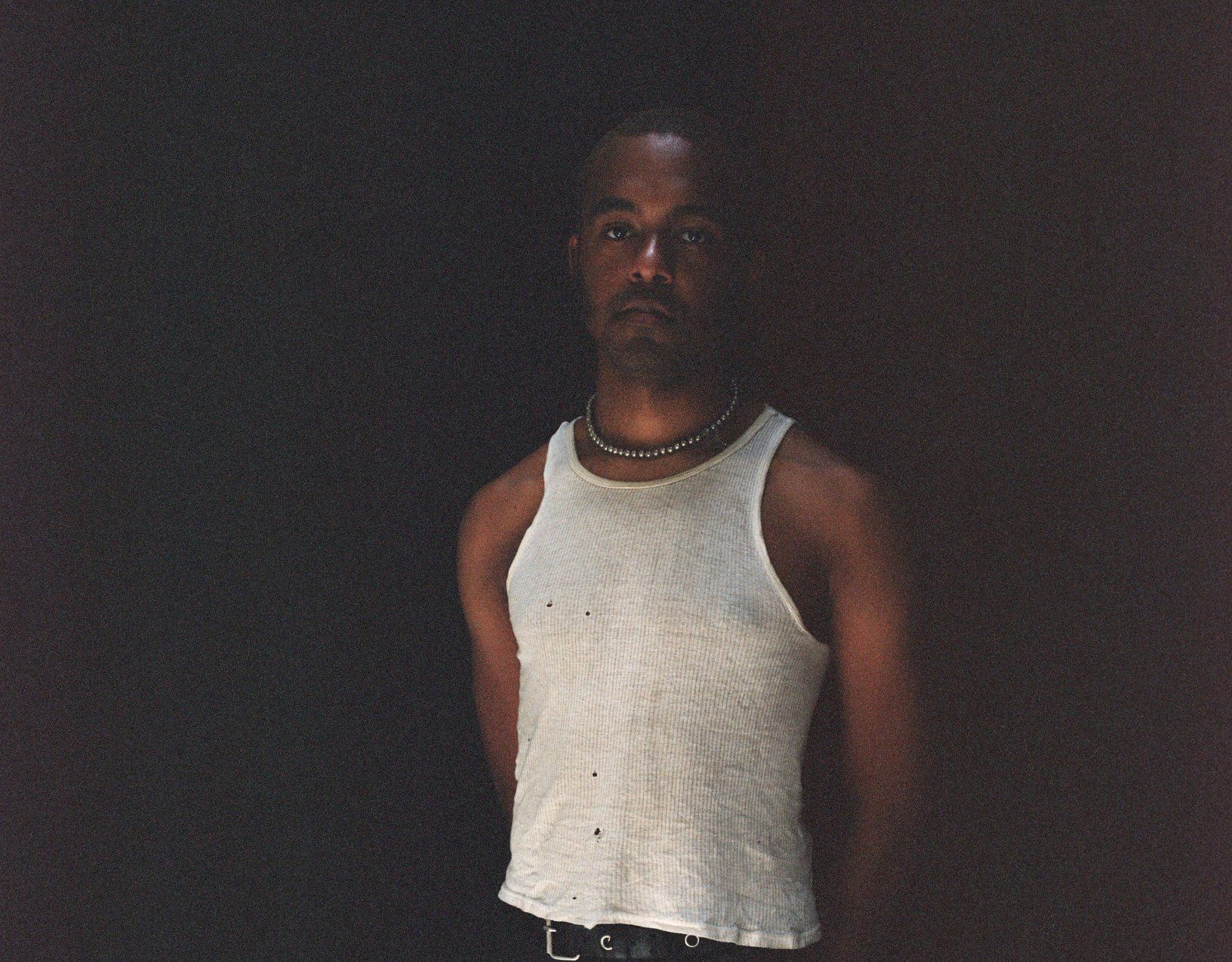

An Exorcism of a Prior Identity: Jasper Marsalis (Slauson Malone 1)

|PHILLIP PYLE

In order to perform an “exorcism of a prior identity,” artist Jasper Marsalis added a “one” to his moniker Slauson Malone.

He also left the overwhelming masculinity of his music community in New York and moved to LA, where he has expanded on his musical and performance project Slauson Malone 1. Described as “exploring the possible intersections of popular music and performance art,” Slauson Malone 1 in many ways functions as a live corollary to Marsalis’ visual practice, where the stage and the canvas are cast as spaces susceptible to the fraught gaze of audiences.

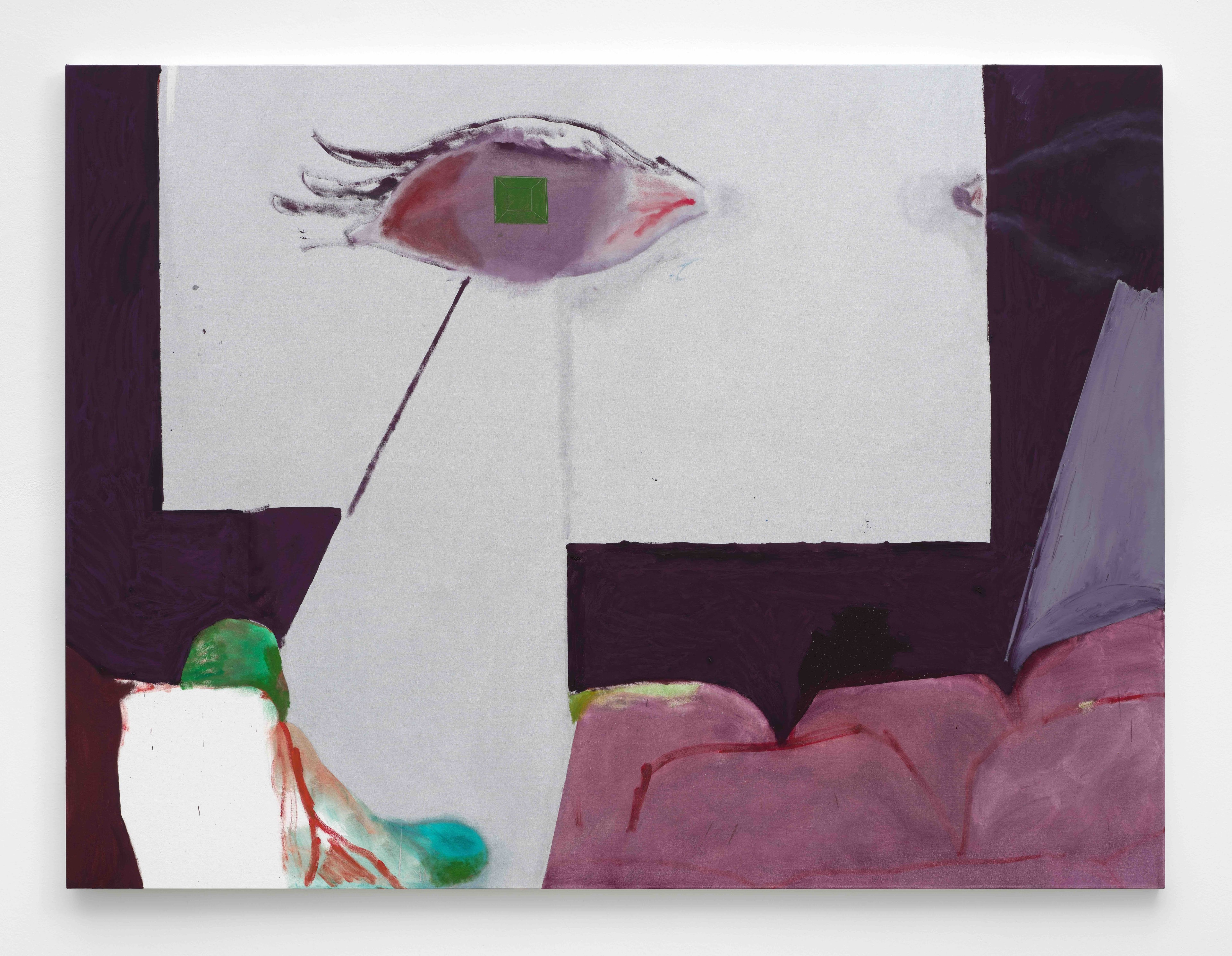

Performance and an inversion of expectations are two of the fundamental links between Marsalis’ seemingly separate art and musical practices. In his visual practice, including the ongoing “Event” painting series, the optics of performance are interrogated through murky portrayal of disco balls, stages, spotlights, crowds, and microphones. Devoid of clear-cut human figuration, Marsalis abstracts familiar objects in a manner similar to his musical performances, where he utilizes unexpected sounds and spontaneous noise to disrupt the typical audience-performer relationship. For The Stone Breakers, a pair of recent performances at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris and Haus der Kunst in Munich, Marsalis “borrowed technique of exposure therapy from behavioral psychology to blur, if not disintegrate, the established boundaries between performance and audience.”

In 2019, Marsalis released his debut studio album A Quiet Farwell, 2016–2018 soon after leaving the acclaimed Brooklyn avant-garde musical collective Standing on the Corner (most known for their production for Solange and Earl Sweatshirt). At the end of last year, Marsalis released Excelsior, an album whose name is taken from the New York state motto and whose meaning of “ever upward” Marsalis interprets as a constantly growing sword that eventually splits the Earth in two. Featuring over twenty instruments and elements of jazz, hip-hop, pop, noise, psych rock, and no wave, Excelsior is Marsalis enhancing and enlarging his sound to both the cosmos and the minutiae of being.

Phillip Pyle sat down with Jasper Marsalis before his performance opening for Kim Gordon and Sun Ra Arkestra at SummerStage in Central Park to discuss the influence space has on a performance, embracing slowness, and the forms that transfix him.

PHILLIP PYLE: You’re performing on Thursday at SummerStage in Central Park. Will this show be different than the others on your US/EU tour?

JASPER MARSALIS (SLAUSON MALONE 1): Sort of. We’re fighting against time because it’s only a 35-minute opening slot. Someone once told me that opening slots are just to fill time, so it will be like rushed homework.

PP: I was looking through the Crater Speak catalog and noticed that there’s a Sun Ra image in it. I’m sure it’s special to be playing with the Arkestra on Thursday.

JM: It’s a huge honor, but I have a sort of antagonistic relationship with Afrofuturism. That has nothing to do with Sun Ra Arkestra, though. It’s independent of it.

PP: Why antagonistic?

JM: I think it’s hyper fixated on procreation, or the idea that the future needs to be bred. I feel quite critical of it. It’s just the idea that you could find liberation elsewhere, or this idea of being a fugitive. Then, thinking about colonialism, conceptually, obviously, we’re not going to go to Mars…

PP: Something that links your visual practice with music is performance. How has it been performing Excelsior? Has it taken on any different modes for you?

JM: Not so much. It takes a while for me to figure out how to incorporate recorded music into a live context. Nicky [Wetherell], who plays cello, and I have learned so much just playing with each other and getting to know each other. Excelsior does have a lot more acoustic moments in the live show, though.

PP: You’re playing the Getty on June 15th, and you performed The Stone Breakers at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris and Haus der Kunst in Munich last month. Is there a clear difference between staging a piece for an art institution versus a concert venue?

JM: The audience is the biggest difference—and the resources. We get more money to hire other musicians, so that’s always a plus. But the audience is a bit stale. In an art context, nothing is surprising or shocking because artists have already come out of the closet in a way. I mean, artists have put shit in cans [laughs]. There’s nothing you can do. With music venues, the audience has more expectations. They’re more spoiled.

PP: How were The Stone Breakers performances?

JM: They were really great. It’s a bit of a challenge to have such a short window of rehearsal time. We only had two days. Similar to working with Nicky, it’s always such a privilege to work with musicians and learn about their instruments. Like, the bass clarinet is such a crazy, wild instrument if you ever get a chance to be around one. Even without it making noise, it looks so weird.

PP: There are a lot of objects associated with performance in your paintings, including disco balls, stages, and mics. There’s this focus on spectacle but also an obfuscation of clarity with these objects. What are your thoughts on opacity?

JM: [Édouard] Glissant, yeah. It’s simpler in the moment of visual saturation. If someone takes a photo of you—this moment when the flash hits your eyes and you’re temporarily blinded—it’s such a violent experience, but also exciting. I try to capture that experience, visually and emotionally. It’s also a cool experience because you get the inverted image stuck on your eye. You’re walking around with this black spot on your eye.

Sound is no different, like when something’s really loud and you hear this tinnitus, this ringing.

PP: Do you try to recreate that with live shows?

JM: Exactly, or in a painting. These thresholds of what the eyes and ears can handle.

PP: Some of the song titles on Excelsior are highly conceptual. There’s “Undercommons,” for instance, which references Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey. Could you talk about the particular concepts that inspired the album?

JM: With that “Undercommons” reference, I was thinking about the weather. I can’t remember exactly what I was trying to quote, but I remember it was something to do with the weather.

With Excelsior in specific, I was thinking about coming out of a very male-centric music environment and how you perform an exorcism of a prior identity, which is also where Slauson Malone 1 comes from. Super explicitly, “New Joy” was the first time that I ever experienced anal pleasure. I wanted to make a song because it was the most intense experience. Each of the songs try to unpack it, this deadening.

PP: The male-dominated community you were in was in New York. How does it feel to be back in New York now?

JM: It’s like having candy. It’s really nice, but it sits in the back of your mouth and then kind of coagulates. But it’s nice, I’m not trying to seem negative.

PP: Two of the things that struck me with Excelsior were the tempo changes and a general sense of speed at moments. I also saw that you included Aria Dean’s “Notes on Blacceleration” in Crater Speak. What’s your relationship to speed and acceleration?

JM: I used to really love speed as an aesthetic thing—because it’s so impossible to capture two-dimensionally. Or, even on 4D, like in video, everything just doesn’t look right. I guess blurriness equals speed in 2D.

I started to get a real phobia of speed because I thought about futurism and its relationship with fascism. Now, I just want to be slow or work at a steady or sustainable pace. Speed can have a very liberating side to it, too. Dance music, like 180 BPM, is such a liberating sound. [Laughs]

PP: [Laughs] Like nightcore. Do you find that it’s easier to make room for slowness with your visual work than with music?

JM: Yes. Luckily, I don’t care so much about my persona as an artist. Whereas in music, I definitely care about my external persona. It’s like these two desires are fighting each other.

PP: Do they collapse very often? The Stone Breakers shows in Europe seem like a moment where the art institution triangulates the two practices.

JM: I haven’t had the freedom yet to fully collapse them, but there are moments where they bleed. During The Stone Breakers performances, there were these screens that are meant to distract the audience from the performance. This is something I’ve been thinking about in the painting space, having these little squares that are like attention suckers. So, it’s cool to bring that into the performance space.

PP: Your bowling ball sculptures function as portraits in a way, especially with the titles, Ruth (2023), Jennie (2022), and Head (2022). They’re similar to your paintings because they’re portraits through relation rather than explicit depiction.

JM: Bowling balls are such intimate objects to me. When you die, or when you decide you don’t want to bowl anymore, your name is still carved into the ball. It becomes this proxy for another person—with your fingers, different sizes, and different weights.

But there’s something dumb about a bowling ball, in the way a rock is dumb. It just doesn’t say anything to you, and it won’t reciprocate anything. Then, I was thinking about rock music and the sound of a bowling ball hitting the ground, and how it has the same energy of the first beat of a punk song.

PP: I interviewed the artist Mire Lee a bit ago, and she also talked about this idea of dumb or stupid forms. They seem compelling because they get to the point as quickly as possible.

JM: I definitely stole that from [Philip] Guston. That’s something that he would always mention—the dumbness and the stupidity of things.

I think it’s also a way to slow things down. Even though you arrive at the point quicker, like you can identify what it is, the way that you feel about it can take a long time. In the same way that you look at something in nature and just sit there.

PP: You often use round shapes or orifices in your work. Then, the Excelsior sword is phallic. It’s more piercing. Is that a type of form that you want to continue investigating?

JM: No, no. It’s so awkward because even though the combination of the wedge into the bowling ball is such a yucky thing [Jennie, 2022], what it creates is such a stagnant object. It can’t move anymore. The wedge can’t wedge anything anymore. So, they weirdly stop each other completely. That’s more what I’m interested in.

PP: A kind of inertia?

JM: Yes, rather than making a dick or a yonic sculpture.

PP: Are there other forms that have been compelling you?

JM: I think making things look enhanced and enlarged. There are sound sculptures [“Instrument” series, 2022] where I’ll amplify the floor or the stairs, where the smallest movements become really loud. There’s another one that’s a screen that tracks people’s faces [Face 2, 2023]. It makes them the size of the screen, but you also get the distortion of the aspect ratio, so your face will be really wide. [Laughs]

PP: Like a badly saved image.

JM: I like that. Enhanced, enlarged, louder. It’s also quiet because you’re getting the small movements in the wood or the tiles that are scraping each other.

PP: Does that “enhanced, enlarged, louder” approach apply to all your performances, too? Or does playing in a public setting change things?

JM: I try not to think about it because I want to give people the choice to experience the most genuine version of it. If I get too in my head about it, I start changing the performance to become more accessible, which is not the point. I think treating people as if they’re dumb is mean. I would just rather do it and give people the freedom to choose to accept it or reject it.

PP: Are you working on any other concepts for live performances?

JM: I’ve been thinking about making stuff with a player piano. I’ve been working with Max/MSP/Jitter coding to make patches. One piano plays all the notes on the piano at once. It keeps the sustain pedal on, so you hear this beautiful resonance—which, I guess, is similar to a bowling alley, where you hear a “click” then another “click.”

PP: Had you worked with this technology before?

JM: No, it just happened by chance, and it ended up working out. I had been thinking about this chess robot Automaton a lot, which is also related to dumbness. The image of life looks impressive but, once you learn how it works, it’s ruined.

I have a pitch tracking software and the piano tries to play along, but it does such a miserable job. There’s something compelling about it. It arrives at something human through the limitations of the hardware.

Credits

- Text: PHILLIP PYLE

Related Content

HR GIGER & MIRE LEE: Horror, Slime, and Satanic Eroticism

“If people think what I do is shocking, it’s because they’re not used to watching something interesting”: MYKKI BLANCO Photographed by MARLEN KELLER

Runway Music: Electro-Indie-It-Girls

Gross AI Spam with Cory Arcangel

Discovering the Aura with Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo)

Art World Resorts: A Remedy for Chronic Anxiety

ALEXANDRA BIRCKEN: Bodyrevolt

Art World Resorts: artgenève

LEE “SCRATCH” PERRY

Transmissions: The Road of Trials