The After-effects of Painting With Azize Ferizi

|Eleonora Milani

Artist Azize Ferizi and writer Eleonora Milani met in DMs. Here they discuss the transition from painting to sculpture, the relevance of a palette, and the artist’s deep connection to fashion.

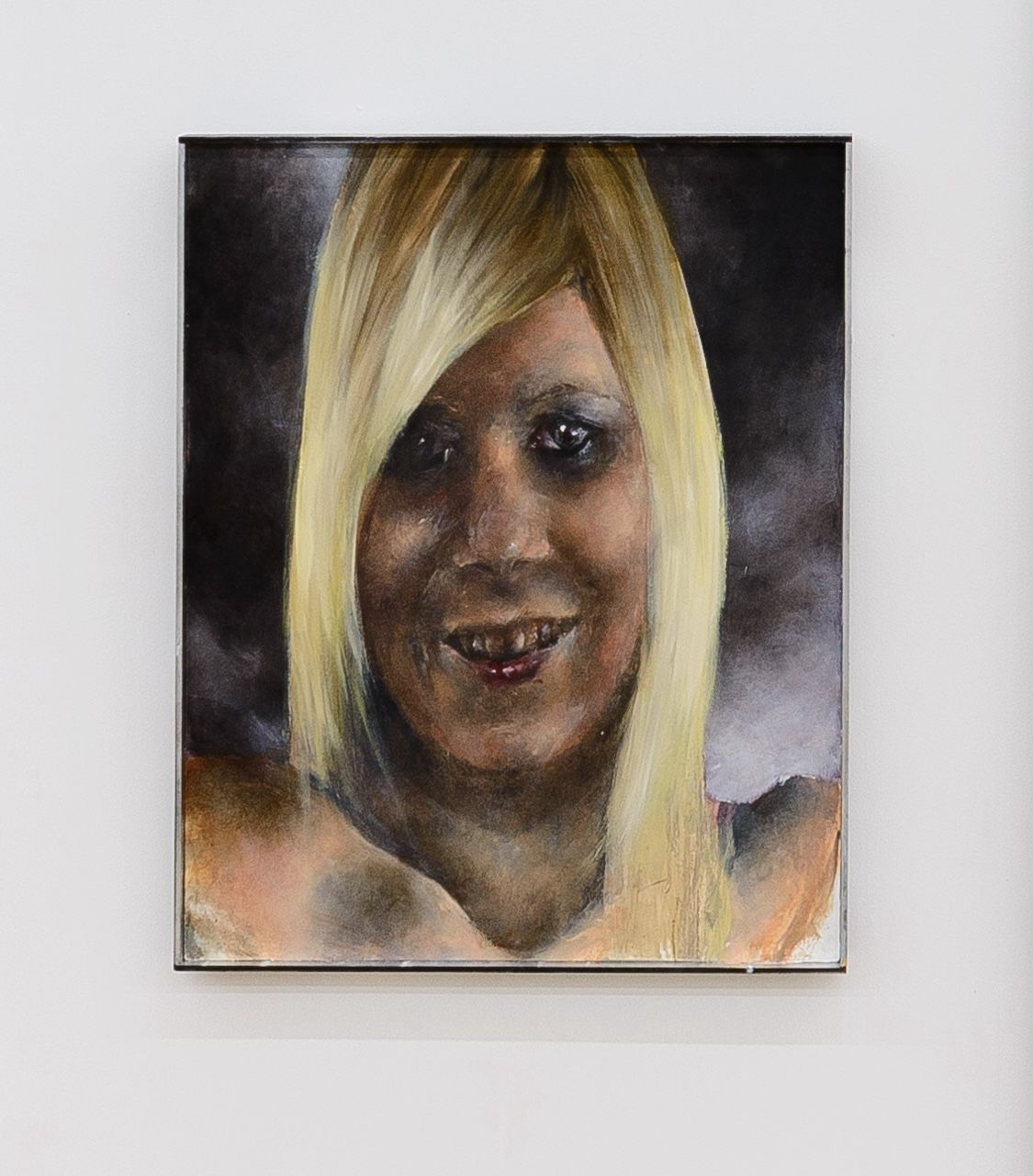

Art Basel in 2022 was so good. Hot weather, good art, good company, good vibes. On my last day in the city, I found my gem among the winners of the Kiefer Hablitzel Prize that year. A large close-up of a disproportionate female body in an atypical palette—earths, ocher, nudes—considering contemporary visual trends and the fact that the artist was born in 1996. Then, to the right at the bottom is a small wooden board hanging on the wall— a toilet painted on wood.

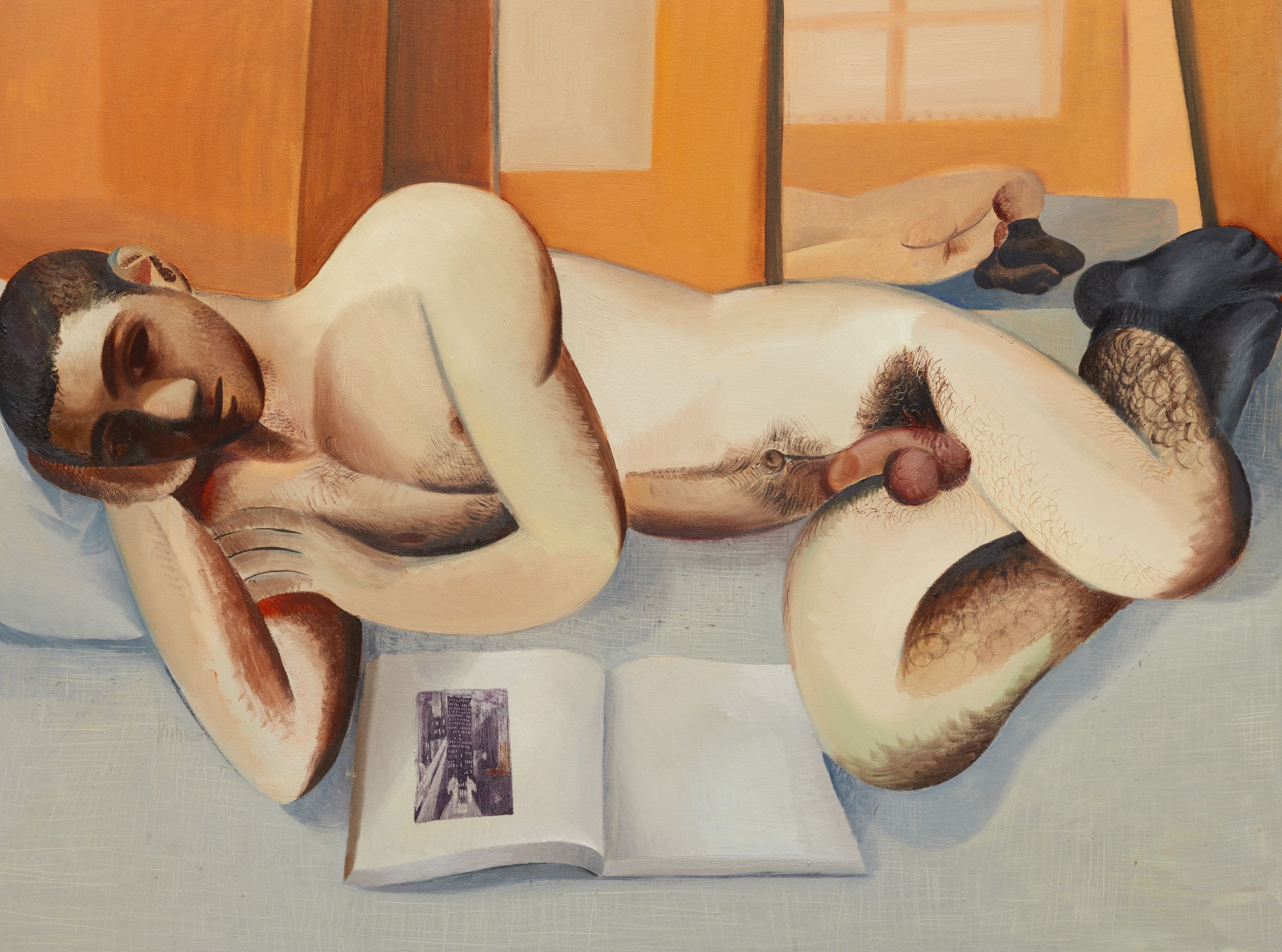

Azize Ferizi and I met each other in DMs. It seemed to me that we had always shared thoughts, but in fact that was not so. I communicated more with her work than with her, until I invited her to show some work in an exhibition I had curated. The work exhibited – The Monk (2023) – in my opinion embodies a leap: from painting to object— a “sculptopainted object.” Everything is in that leap: the influence of her residency in New York, her occasional work in the fashion industry, and her constant research for the meaning of painting today. That in-between horizontality and verticality has always been the unresolved dichotomy of art, and the gray zone between the two is often more interesting. Ferizi also prefers gray zones.

In this conversation, which is the result of many in-person dialogues, text conversations, and zoom calls, Eleonora Milani discusses with Ferizi the transition from painting to sculpture, the relevance of the palette, and the artist’s deep connection to fashion.

ELEONORA MILANI: Looking at Robert Morris’ works from the 1960s, an art critic called them “object sculptures.” That’s exactly what I thought when I saw your sculptural paintings—a body of work you started in 2023 and which is still in progress. Painting, in these works, has become an object. You have shapeshifted the canvas and turned it into a sculpture. What’s left of the painting?

AZIZE FERIZI: The main thing that interests me in paintings, compared to other artistic media, is mostly the domain of colors and palettes. I started with figurative paintings, with a strong need to create an ensemble of similar palettes. Oil is good for that because you have a good base to research different colors and mostly experiment with the theory of color. So, first it was how to experiment with colors but through figurative painting. At the same time, I have always appreciated abstract painting and minimalism as well. I have wanted to start doing abstract paintings for a while now, but I am too immature and still stuck with figurative images—even though I have always wondered how I could experiment strictly with colors and distance myself from figurative paintings.

EM: Does making figurative painting mean staying in a comfort zone?

AF: Not at all, I think you need to be comfortable enough with figurative shapes and colors to then be coherent in abstract work.

EM: Speaking about your childhood between Switzerland and Kosovo, you have told me that this female world from which you breathed fashion and attention to self-care worked very manually. So, the domestic space became an important driver in your growth and in the development of your visual landscape. Is that why you look to artists such as Chantal Ackerman?

AF: Definitely. I didn’t quite understand her work when I first saw the video La Chambre [The Room] which is a 360-degree shot of a woman in her room in Brussels. Not much happens in this scene. But I connected with that restrained position of a physical body inside a certain territory or situation, even though her work wasn’t going in that direction? Growing up as a Swiss-Kosovan I was very aware of how much we are limited physically by our political status, and how the legal status of free movement of people could determine one’s life. Being a woman was also socially restraining in many forms, from your behavior to a different treatment in general from men. Her images always draw a parallel with that state of feeling stuck and becoming an observer contemplating your life instead of acting in it, which then resulted in my paintings of these scenes of women in an interior, alone.

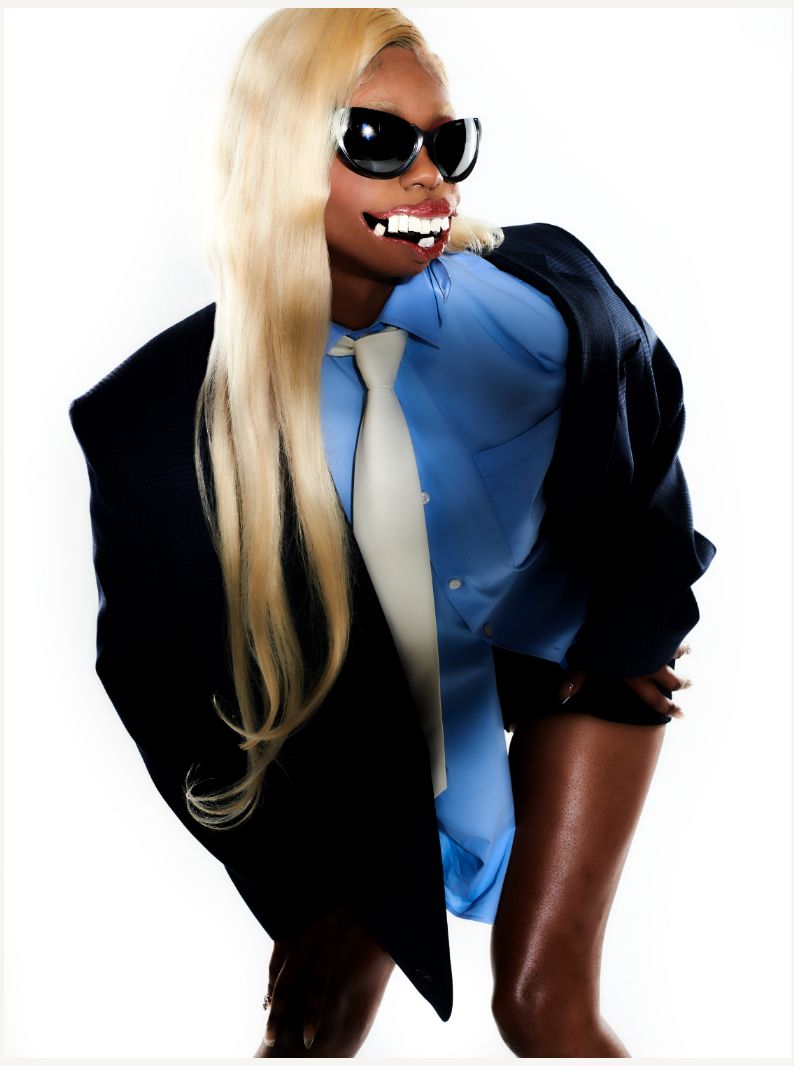

EM: Then New York City. And something changes, maybe everything. Your familiarity with styling and fashion finds a way into your practice and vice versa.

AF: I went to New York from September 2022 until February 2023 for an MFA at SVA [School of Visual Arts New York City]. There, I would help friends with styling or shooting. But my main activity was to go to the Met Museum every week to see the garments/clothes/fashion archives. I was obsessed and would also make the link with the paintings exhibited there and just have fun drawing shapes from that or doing palette research based on the fabrics I would see there.

It was kind of like a game for me. I went out of this isolating cocoon that a painter can get stuck in when practicing. Working in a team was so fun and exchanging ideas with others then made it easier to dive further into a project. When I came back from New York, I was very frustrated with my work, especially with my figurative painting. I realized I was missing this contact with a shape and/or with a body, something that I could mold and give a personality, a character. Something that is more alive than just a canvas fixed on the wall. I started this first series “Chronicle Events,” which I showed at the Basel Social Club with Cherish [June 2023]. This was the first time that I exhibited my sculptures, and it was very spontaneous. I took the canvas, but I didn’t want to stretch it on a frame. I thought, “Why can’t I use the canvas as a material, as if it was a fabric that I could just cut into, and try to make this appearance of a woman posing in a certain way and create a fiction around these shapes?”

EM: It was these works that made me think you had a background in fashion.

AF: I’ve always been inspired by fashion, because all my aunts loved it and so did my mom, or at least they loved a sense of style. They always used to take hours and hours to dress or put makeup on, so I have always had this interest with appearance through clothes, make-up, and hairstyles. I started this series, and I just tried without really knowing the result.

It was funny because I always found it interesting when artists blur the line between their practices. You can be a fashion designer, an artist, a sculptor, a painter. I always thought it’s good for your creativity anyway. It was very nurturing for me to start this new practice through sculptures and notto feel restrained in my position as a figurative painter.

EM: It seems that everyone, at some point, ends with figuration, albeit not without after-effects and disillusionment.

AF: I’m so stubborn, I tried to only paint figuratively for as long as possible. I am still inspired by all the Renaissance, Neoclassicist, and Flemish figurative paintings. I had a very pretentious point of view on abstract art when I started to study art. I was like those annoying people who say, “Oh my kid could paint that.” I thought in that way. And now I hate it when people say that.

EM: What if this kind of need is linked? I feel it’s a generational issue, how about you?

AF: Oh, definitely. Especially if you’re an art student in Europe. At least in Switzerland, I mean it’s logical because there are quite a good number of abstract/minimalist pioneer artists. But personally, I have always missed the point of conceptual/minimalist art pieces, I have always thought I am not smart enough to get it or even to make it. It can be very intimidating if you don’t have a solid background in art.

EM: I feel like painters are a bit stuck in this in-between state, wondering, “Where are we going?”

AF: Exactly. I talk to friends who are also painters a lot. It’s very frustrating how we don’t really know where to position ourselves anymore in terms of techniques and images. The act of painting is very ancestral, one of the first human forms of expression. This is very different from images today that we can create in a second through AI.

EM: Since the year 2000, a shift has been happening in terms of its intrinsic meaning. I think that this inability to position is the shift.

AF: I think that the shift started the moment we stopped knowing why we were painting. Again, with every painter that I talk to, sometimes you feel so alienated when painting. Before the internet or at least before photography, there was a purpose in the way of depicting reality, that you needed to draw or show some images that were necessary to paint or consider it as a patrimony for the next generations. Today, we have access to so many ways of creating images. It’s not negative, just different.

EM: In our chats, there is one thing I have never asked you: what’s your dream?

AF: Painting takes a lot of time alone, which feels amazing when you need to. Then there is a point at which we need more dialogue between artists. In my opinion, this is something which we have less and less nowadays. I was amazed when I read the book Almanach ECART when it came out in 2020. This is a book that records the archives of the Ecart collective—co-founded by John Armleder, Patrick Lucchini, and Claude Rychner—and it records practically all the exchanges they had with other artists in Switzerland, Europe, and New York from the 60s until the 80s. It talks about performances, events, correspondences, letters, drawings, etc. There was a physical trace, something we can now grasp years later and have a proper image of what was happening at that moment. Now most of my exchanges are digital, and I’m worried. So, I would say one of my dreams would be to bring this back. For example, I have recently started to write letters or send collages to friends in LA, New York, Switzerland, and Paris, and to ask them to send something back. I don’t know where this could go but let’s see. It’s a beginning.

EM: At what age did you become interested in fashion?

AF: Around 11. I remember that when my sister had her first job, I asked her to buy me Vogue. Then there was this channel called Fashion TV. I thought it was an American channel but it was French. I don’t think there was a reason why I was attracted to it. But the music was sexy, and the girls looked chic and funny. TV and pop culture were intriguing, it was a way for me to connect with the outside world. I grew up in Charmey [in the district of] Gruyères, which is far from everything and any city.

EM: You started this conversation by talking about palette. What does color mean for your idea of an art object?

AF: The importance of color came to me through fashion magazines. I would do collages, and compositions of colors and shapes when I was a teenager. Then I started a long process of research with oil. It’s a practice that can be developed infinitely. As oil painters, we have unlimited ways of experimenting with colors, pigments, and textures. So, it’s more linked to practicing and bodywork, than it is to thinking or planning it.

EM: Yeah, or more just a way of seeing manual work, something more artisanal.

AF: Yes, I grew up with lots of family members who were artisans. My grandfather in Kosovo used to make carpets with furs from animals he had on his farm. My grandmothers used to spin fibers. My uncles worked in cheese factories in Switzerland. My father is a carpenter. These two countries have a lot of artisanal work, so it was interesting for me to also experience my way of producing something that takes time and practice.

EM: Maybe that’s why, in your body of work produced since 2022, the colors look so naturally embodied in the canvas.

AF: It is. When I started painting, I always thought it was interesting to develop my own palette. Especially with oil painting, you have so many different possibilities and different nuances through pigment. I always took a lot of time to experiment with colors before starting an actual painting. Mostly, I used to have these small samples of Pantone cards, like, I don’t know, 200 cards of different shades, just to have an idea of the palette I wanted. Then I would slowly start to build my own palette using the same tones repeatedly. I like to recognize a painter by their palette. That’s really hot! It’s a nice compliment when someone says: “Whatever paintings you make, we recognize your palette.”

EM: I’d say it! It’s a Renaissance palette, sort of. Even your blue is linked to Christianity. Which looks like a paradox, compared to your shapes.

AF: Yeah. For me, when I started to be interested in painting, it was mostly through religious, Renaissance paintings. The deep green on a fabric of van Eyck, a piss yellow from Piero della Francesca, or a contrasted blue of Vermeer. I always found it funny to recreate this palette, but with a completely different language or image at the end. I think that’s the essence of painting. It’s all about colors.

Credits

- Text: Eleonora Milani

Related Content

Image Spamming with Paul Hameline

Reality TV as a Sociological Analysis: JAMES BANTONE

Selling leggings at artmonte-carlo: MOHAMED ALMUSIBLI

LOUIS FRATINO Paints Gay Intimacies

KRISTINA NAGEL’s Landscapes of Depersonalizations

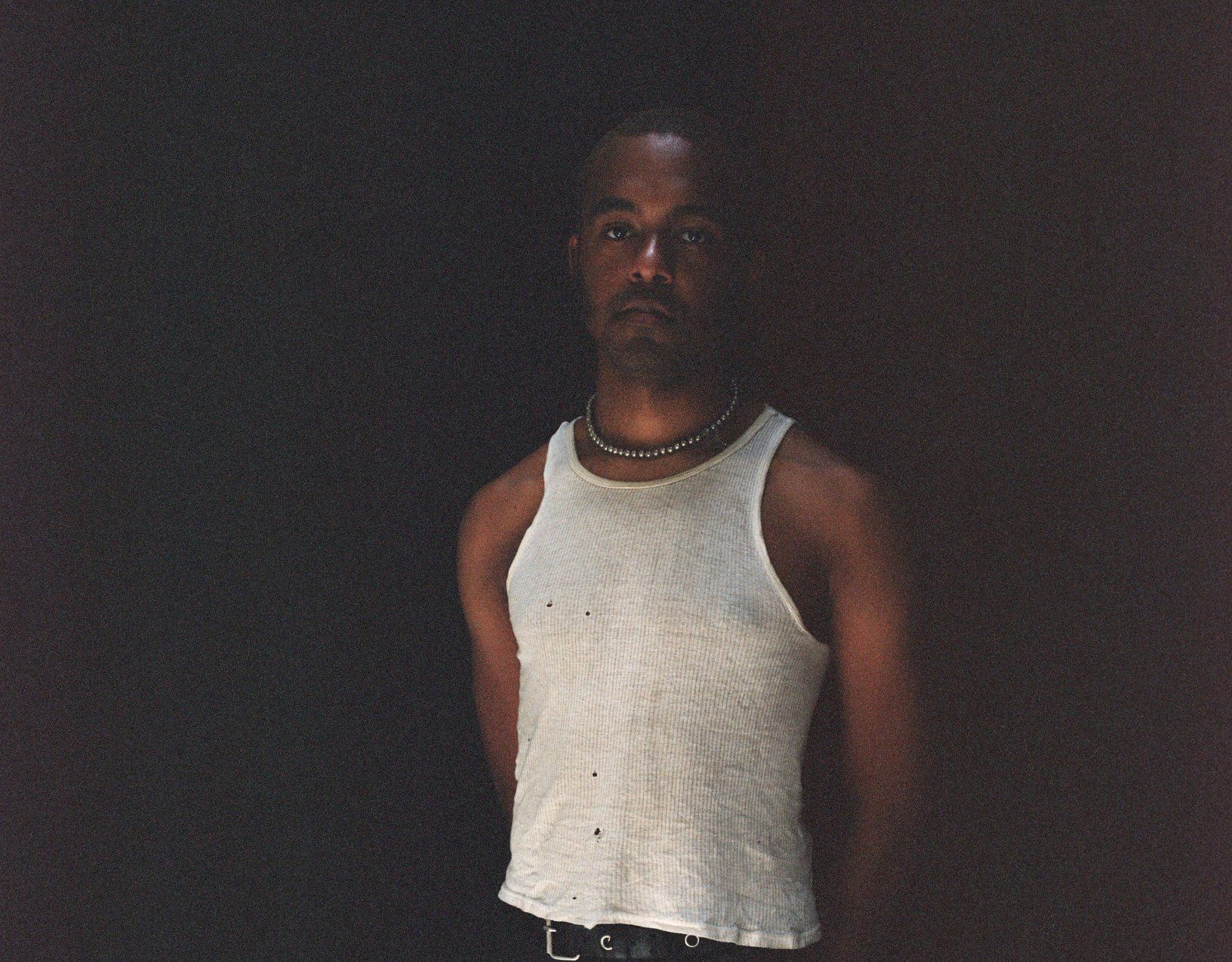

An Exorcism of a Prior Identity: Jasper Marsalis (Slauson Malone 1)

DAVID OSTROWSKI Brings Bauhaus to Warsaw’s Galeria Wschód

Image Stacks With ISABELLE GRAW

The Undercurrents of Materials: CUDELICE BRAZELTON IV

Other People: SER SERPAS

Erwan Sene’s Sonic Odyssey

A Martine Rose Slip: JORDAN/MARTIN HELL