Image Stacks With ISABELLE GRAW

|Ana Viktoria Dzinic

Image Stacks is 032c artist in residence Ana Viktoria Dzinic’s new series that takes a psychoanalytical gaze at the camera rolls of key figures in the culture industry.

For the first edition, she speaks to art historian, critic, and co-founder of Texte zur Kunst Isabelle Graw about the looping monologue of anxiety and the semantics of gallery dinners.

Since we all know, one image says more than a thousand words.

ANA VIKTORIA DZINIC: Thanks for sending all the images. I love the fact that you shared each image one by one via email. I could visualize you scrolling through your camera roll and finding all these images and sending them to me.

ISABELLE GRAW: [Laughs.]

AVD: If you think about image making, it seems like an essential part of our lives. Boris Groys states in his book The Logic of the Collection that art players must inhabit the mindset of a freelance photojournalist, giving form (i.e., documentation of their labor) to their content (i.e., exhibitions, books, art works, magazines). Would you agree with this thesis?

IG: I think I would put it differently than Groys. I suggest a more historical lens. Since the mid-20th century, we have been living in a media society that is governed by the laws of celebrity culture, and these conditions do not only pertain to actresses and singers but rather to everybody. The digital economy in particular forces everyone to stage their lives and perform their labor in some way or another. And this is particularly true for people who work in the cultural sphere.

Yet, I find it quite challenging to construct images of me and my work in such an environment. I try to be somewhat intelligent about it and see it more as a self-reflexive gesture. I'm not interested in using pictures about me and my work only as a tool of promotion. I also need these images to transport the content that is important for my work. For instance, the cover of my book On the Benefits of Friendship (2023) was a very deliberate choice. I used a painting by Elaine Sturtevant, which is replicating Andy Warhol's flower paintings. She could only make these paintings because Warhol was her friend and gave her access to the actual flower screens. However, her gesture is not only one of honoring Warhol. It's quite aggressive as well. She took his most successful motives, the flower paintings, and claimed them for herself. So, this image encapsulates exactly the dynamic that I'm thinking about in the book.

AVD: Let's look at the first image, a photograph of a Merlin Carpenter painting depicting Amy Winehouse. Can you explain why you took this image?

IG: It's a painting that was gifted to me by Merlin Carpenter and is currently hanging in my living room. I like this work a lot, and I keep thinking about it. The work is part of a series called “Decades,” using Warholian mannerisms of stars, and each star in the series stands for one decade. So, for the 50s, you have Audrey Hepburn, followed by Michael Caine for the 60s, then Blondie for the 70s, Scarface for the 80s, Kurt Cobain for the 90s, and finally Amy Winehouse for the 2000s. These paintings are supposed to look like cheap posters often found in cafes during the 90s. They're very graphic and somewhat empty but at the same time saturated with affect based on the portrait of a star. I am incredibly intrigued by this work and love looking at it because it's not just a beautiful painting. It's rather abstract; the unusual color combinations and the cheap poster effect-briliant.

AVD: Merlin Carpenter is brilliant. Full Stop. I am intrigued by the process of documenting art and the reasons behind it. Tell me more about how you took this image.

IG: I took this very quickly with my phone, right after hanging it. I might have sent it to Merlin and a couple of other friends to show them, and overall, I guess it was for my own personal archive. However, it is very random and I did not think about it carefully. When I look at it now, I think it looks really nice. I guess the formal aspects are that of an amateur cellphone shot and it definitely doesn't do justice to the painting in all its aspects. It's more about creating a little souvenir. Merlin might not be so happy about this image being used. It's a very weird angle.

AVD: It’s perfectly nonchalant.

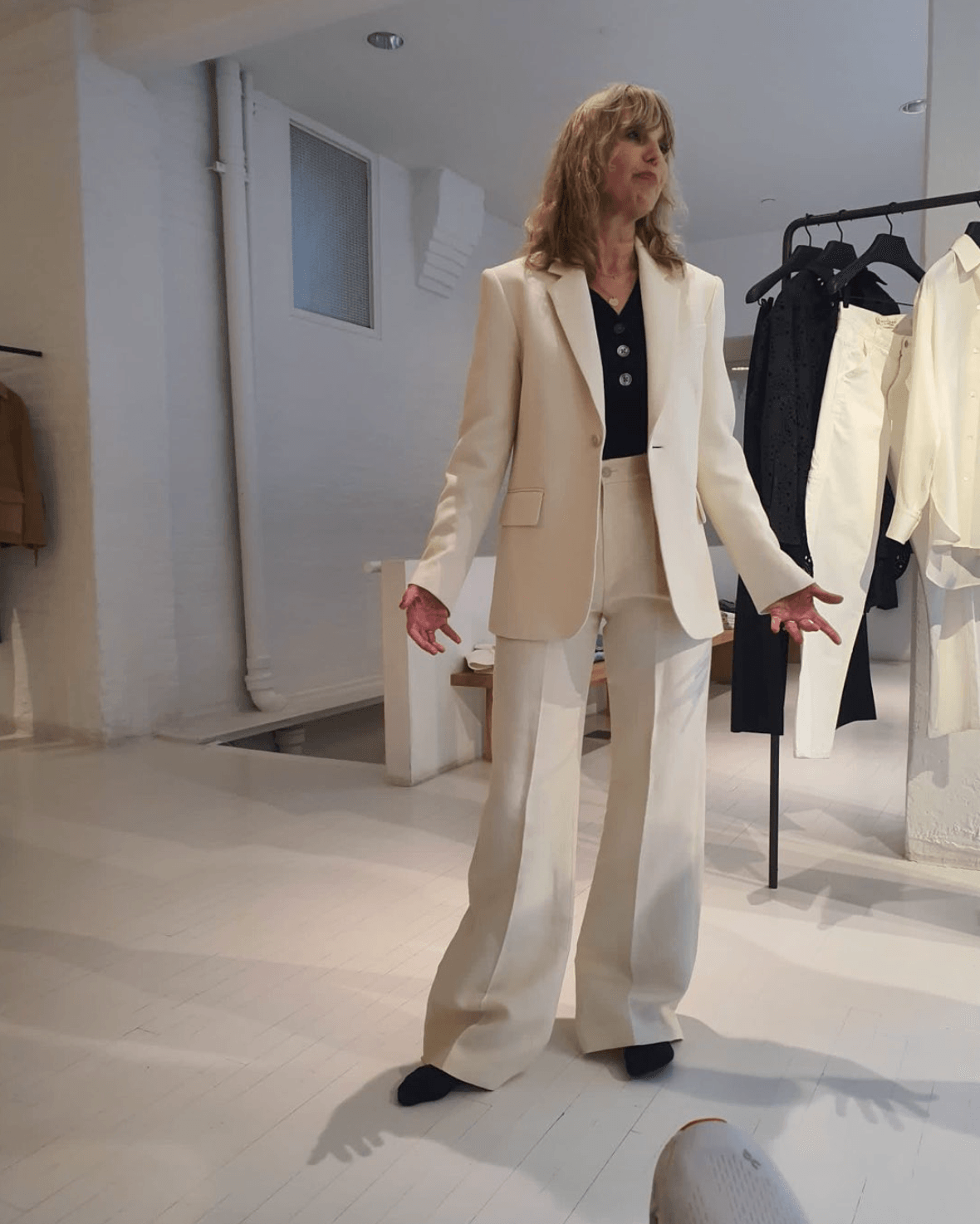

AD: The next images you shared are all of you within your recent exhibition “In Defense of Symbolic Value” at Galerie Max Hetzler. The photographs show you in front of artworks while holding multiple publications. What was your reasoning for making and publishing these images?

IG: First of all, my proposition for “In Defense of Symbolic Value” came from an observation of the art market. On the one hand. in the online sphere -in particular Instagram where a lot of art circulates- it's impossible to understand what is at stake in an artwork, because all the contextual information is missing. On the other hand, there are galleries, mega galleries, mimicking and aligning themselves with luxury resorts, which make gaining access to the art very difficult. This implies that there is no public sphere in the old-fashioned Habermasian sense of the term anymore. This also means that the stake in artistic production of symbolic value doesn't really count here; it's the market value that counts. So, I tried to put the emphasis on that which is symbolically at stake in artworks that I believe have symbolic value. I was also interested in showing artists whose work negotiates these resort conditions and respond to them in different ways. When I chose to put these images on my Instagram account, it was a spontaneous idea.

AVD: Do you think a human in an image is always more engaging?

IG: Yes. I know from experience that if you post a selfie, you get many more likes. If it's only work, you get a lot less likes. Secondly, I was interested in depicting the kind of complicated relationship between the roles of the critic, the curator, and her brochure, where she wrote about these artworks and produced a symbolic meaning for them. Despite my reading, there's also something about these artworks that I probably didn't capture. So, I liked this tension. But I don't really think about these things that much to be honest.

AVD: It is not considered very cool to pose in front of art-even though it seems like the most intuitive thing to do. Is this something you ever think about?

IG: Of course, one could say staging yourself in front of artworks is so cringe. In the past 30 years, this was a total no-go. It was considered something only very tacky artists do. But things have changed. Since the pandemic, I observed a new approach to this: for instance, during the last Venice Biennale, I received many emails from galleries, who sent me pics of their artists posing in front of their work at the Bienniale, smiling. This would have been impossible ten years ago, but it is possible now, due to the pressures of the online sphere and the change of contemporary pictorial conventions. And I may have hinted to that as well when I posed this way and played with these conventions.

AVD: Is this also why you ventured into the field of autotheory? The return of the “I” in academia seems hip and exciting. Do you believe there is still a space in subverting market logic and biography?

IG: Yeah, the “I” definitely came back. However, I think I wouldn't use the term autotheory. I would suggest something like autotheoretical fiction because the fiction part is actually quite important. When both my parents passed away between 2013 and 2015, and when Brexit happened and Trump got elected, I was interested in finding a language for this kind of intensified relation between personal and social/political conditions. I needed to develop a sound that allows for both personal account and critical reflections but smoothly ties the two registers together. I felt that my daily observations and reflections were not ending up in my art historical and art theoretical writing but rather in my diary or in other forms that remained in my drawer. And that was frustrating, so I needed a supplementary outlet. Furthermore, I asked myself: “Who am I really if I'm not defined by my parents' gaze anymore? Am I may be someone else-someone who I could now be because of them?” Then I decided it is now or never and started to write this more aphoristic book In Another World (2020). It brought a lot of pleasure, and it was a necessary practice next to my art theoretical research and projects-it sounds kitsch, but it was an inner necessity. It just had to be done.

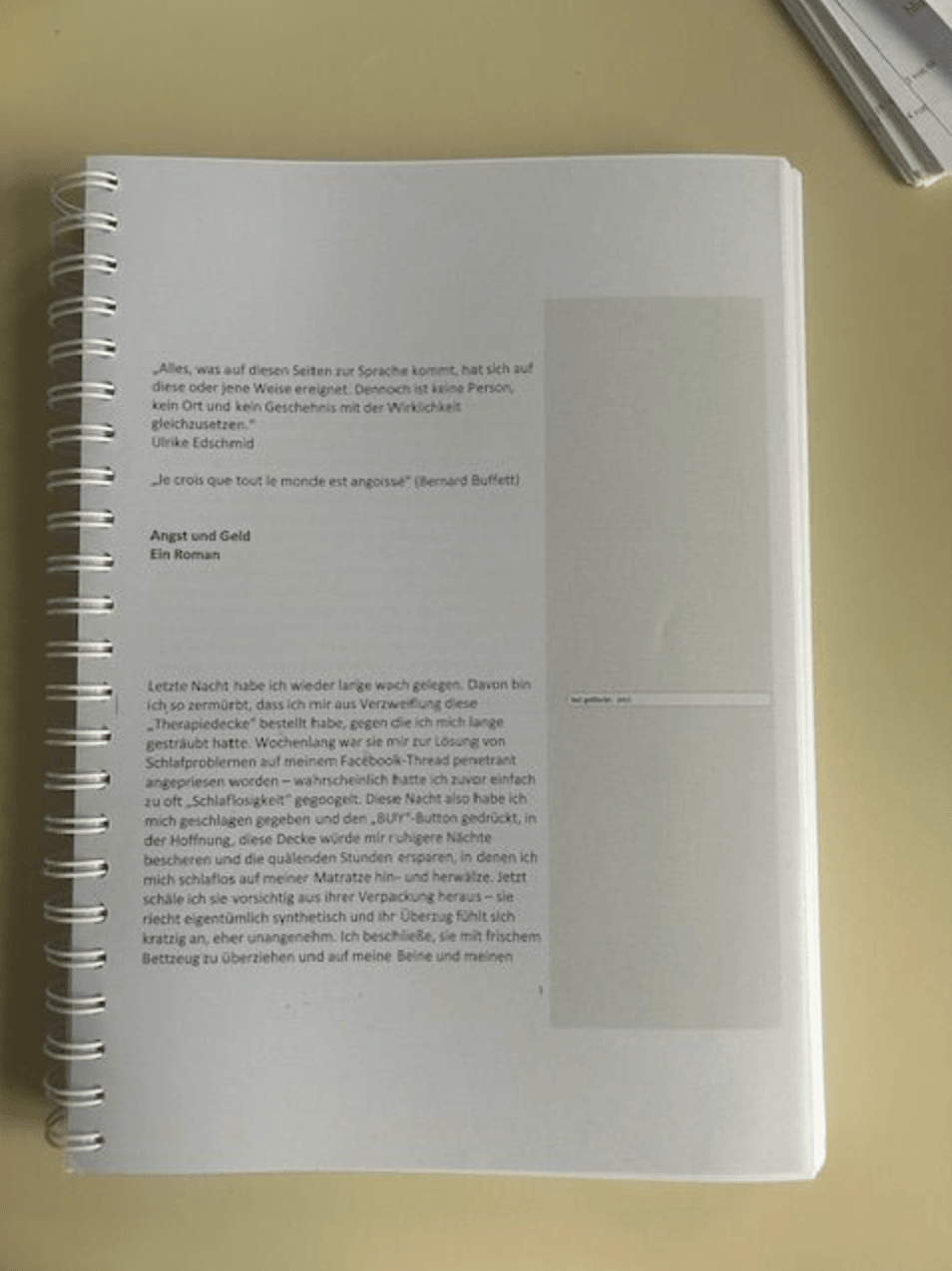

AVD: Iconic! You also shared an image of a manuscript for your next book, and I noticed you published the same image on your Instagram profile. What are your thoughts on work in progress images?

IG: It is not something I usually do. In this case, I wanted to promote my future book, but I wanted to encourage myself even more. I only shared the first page, and the beginning of such an endeavor is rather blissful. The book seems to write itself, and it's a wonderful auto-pilot experience. But then everything that comes after the beginning is very hard the texts need construction, revising, reconsidering. And when I posted this image, I forced myself to make this book happen and to continue to write it, and furthermore decide on the ending for it, because the ending needs to be contained in the beginning already. And it’s very hard for me to end a book—you want to finish it and leave it behind, but it also has to work as an ending. So, for me, the ending is always the most difficult part. I guess taking and publishing the first page was a self-motivation device.

AVD: I love the idea of self-manipulation by creating and staging evidence for a future reality. This is a methodology I can relate to myself, and I feel like image making is particularly good at it. What is your new book Fear and Money about?

IG: I’m not sure if it will be translated to Fear and Money, because the German word “Angst” is also anxiety. Maybe it will be Anxiety and Money, but this doesn’t sound as good, of course. So maybe it’s Fear and Money in English after all.

I always need a form first, and for this book, it will be an inner monologue modeled after Arthur Schnitzler’s Leutnant Gustl (1900), which is, historically speaking, one of the first inner monologues in the history of literature. Fear and Money resembles a stream of worries about anxiety and money-problems and also offers instances of relief. I wanted to demonstrate that fear does not need an object or be caused by anything. It’s something we are made of in our unconscious. The book is inspired by the psychoanalytical theories of Freud and Melanie Klein and how money, or rather the lack of money, in particular induces fear. I had the urge to write about this because anxiety is a contemporary mental illness that more or less everybody I know deals with, and furthermore money has never been more important or defining as it is today. Again, I was interested in finding a literary voice that is individual but collective at the same time, inverting the neoliberal logic that isolates us from each other and gives us the feeling that we have to find a way for ourselves only. This is a complete illusion because we are all connected, and others are just as stuck, frayed, and neurotic as we are. With the book, I aim to lift above it all and propose how the individual anxiety attack is something that feels very lonely but is actually something that connects you to others.

AVD: Iconic, also the parallel between anxiety and inner monologue—very relatable

IG: I wanted to find a language for this constant dialogue that we have with ourselves.

AVD: You also shared a bunch of images with you and your friends. Have people ever asked you to post a picture of them or to not do such? For example, the image of you and Stephanie LaCava is from when you met her for the first time, and it seems as if taking a picture is a celebration and materialization of friendship.

IG: I haven’t posted most of the pictures that I shared with you. But the Stephanie LaCava picture was taken by my husband. I asked her if I could post it and she was ok with that, since she posts a lot herself and has cultivated a great online persona. I have friends who wouldn’t want me to post pictures, and I know who they are, and I would never go there.

AVD: I also believe one needs to read the room. At gallery dinners, for instance, it is sometimes encouraged to take a picture and other times you are committing social suicide if you do. Have you noticed a social etiquette around image taking behaviors during art dinners?

IG: In the case of the picture with Stephanie, it was important that you don’t see that it’s a gallery dinner, and that you don’t see which gallery dinner it is because I certainly don’t want to show off with that information. It is more centered around our first real life meeting and that we are both visibly happy about this.

Yet, what is most interesting about these dinners, and I’ve written about this in In Another World, are the proposed hierarchies. When you were invited as a critic to such dinners in the 80s and even the 90s, you were often sitting next to a potent collector because the galleries thought that this could be a very interesting and beneficial conversation. Or you were seated next to the artists showing because, as a critic, you’re supposed to be part of the artist’s world. This has changed and the art market has gone through structural transformations, becoming a global industry. Since then, critics and art historians often find themselves at the kids table—you know, with gallery staff, which is very nice and interesting, but you are no longer allowed next to the money people. Money people at gallery dinners are protected and shielded away. Things might change later in the evening, of course, when everybody is drunk and unexpected interactions can take place. So, I’m more interested in a sociological gaze. When I go to these dinners now, I’m always curious: how will I be seated? The seating order is a semantic proposition in itself.

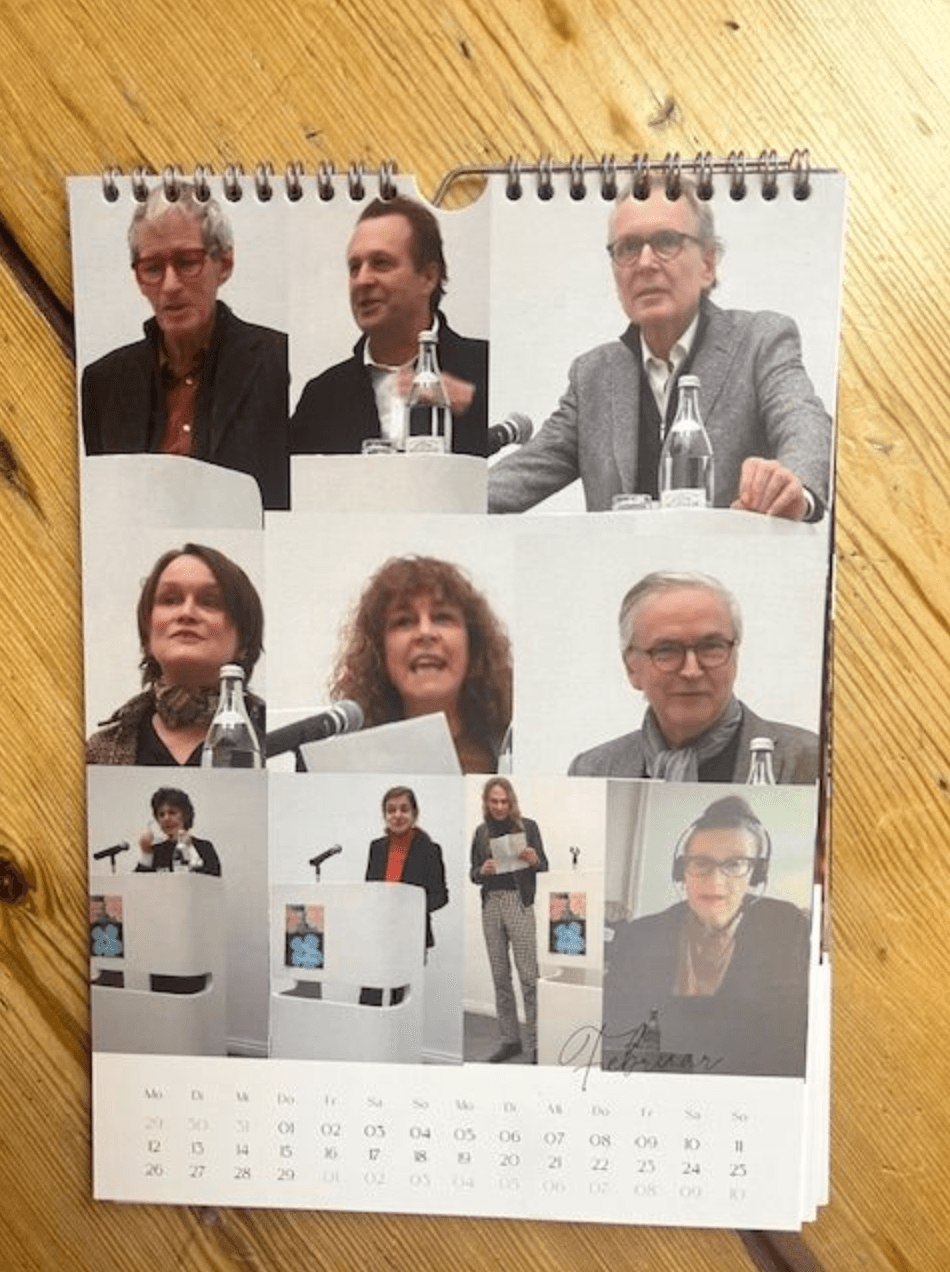

AVD: Lastly, there is an image with a self-made photo calendar. I assume it was a present. I love the idea of creating a story of one’s year in such physical form, using the calendar template as a narrative structure and building a type of monument to one’s own life or merch. Would you ever consider making merchandise?

IG: The calendar is comprised of pictures that my husband took during the academic celebration of my 60th birthday, which was called “The Value of Friendship.” Each of my friends gave talks on me and my work and this experience was incredibly moving and inspiring to hear. In an attempt to commemorate this, he made the calendar. I really like the object, and particularly the photo collage, also referencing the importance of giving talks and lectures, which is a form I think about a lot in my life.

When it comes to merchandising, nobody has ever asked me because I’m always busy writing and my absolute priority is writing. I don’t know if I would have the time. But if somebody said, “I’m going to sponsor this, and do you want to create a lipstick line?” I would be extremely happy to do that.

AVD: Let’s make this merchandise deal a reality. Thank you for sharing these images. I think we should post a screen shot of this, as future evidence.

Credits

- Text: Ana Viktoria Dzinic

Related Content

“We Should Get Her Flowers” by Ana Viktoria Dzinic

The New American Dream Is Sponsored by Meta: ANA VIKTORIA DZINIC

The Concrete Flowers of SVETLANA KANA RADEVIĆ

Metagaze: SHYGIRL Stares Back

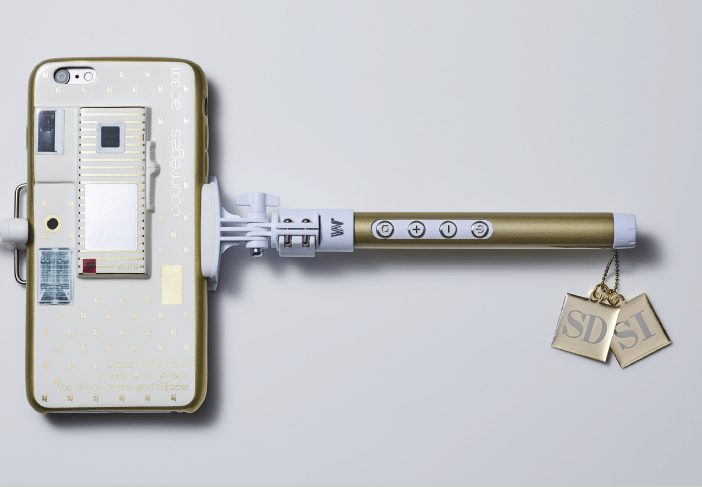

Why SIMON DENNY Bootlegged the World’s Oldest Selfie-Stick

Art Critic JERRY SALTZ and 12 Supermodels Discuss the Selfie

Twisted Femmes: ANNA UDDENBERG’s Uncompromising Sculptures

Every FRANCIS BACON, Ever.