Other People: SER SERPAS

|CLAIRE KORON ELAT

In the final interview before his death, Jaques Derrida noted that he finds his death in writing, leaving cadaverous personifications behind through textualities. His presence meanders through his work, even after his physical decomposition, as his thoughts and ideas continue to exist in his texts, which are accessible for generations today. Predicting one's own corporeal end might be quite macabre, but Derrida did not just reflect on his own death antemortem but on the demise of prominent figures and friends, too. The Work of Mourning is a collection of eulogies Derrida wrote to friends who have passed away, such as, among others, Louis Althusser, Gilles Deleuze, Jean-François Lyotard. The textual mournings, which are at the same time honoring retrospectives, undergird the French philosopher’s ideas around death including the question of who inherits and mourns these traces.

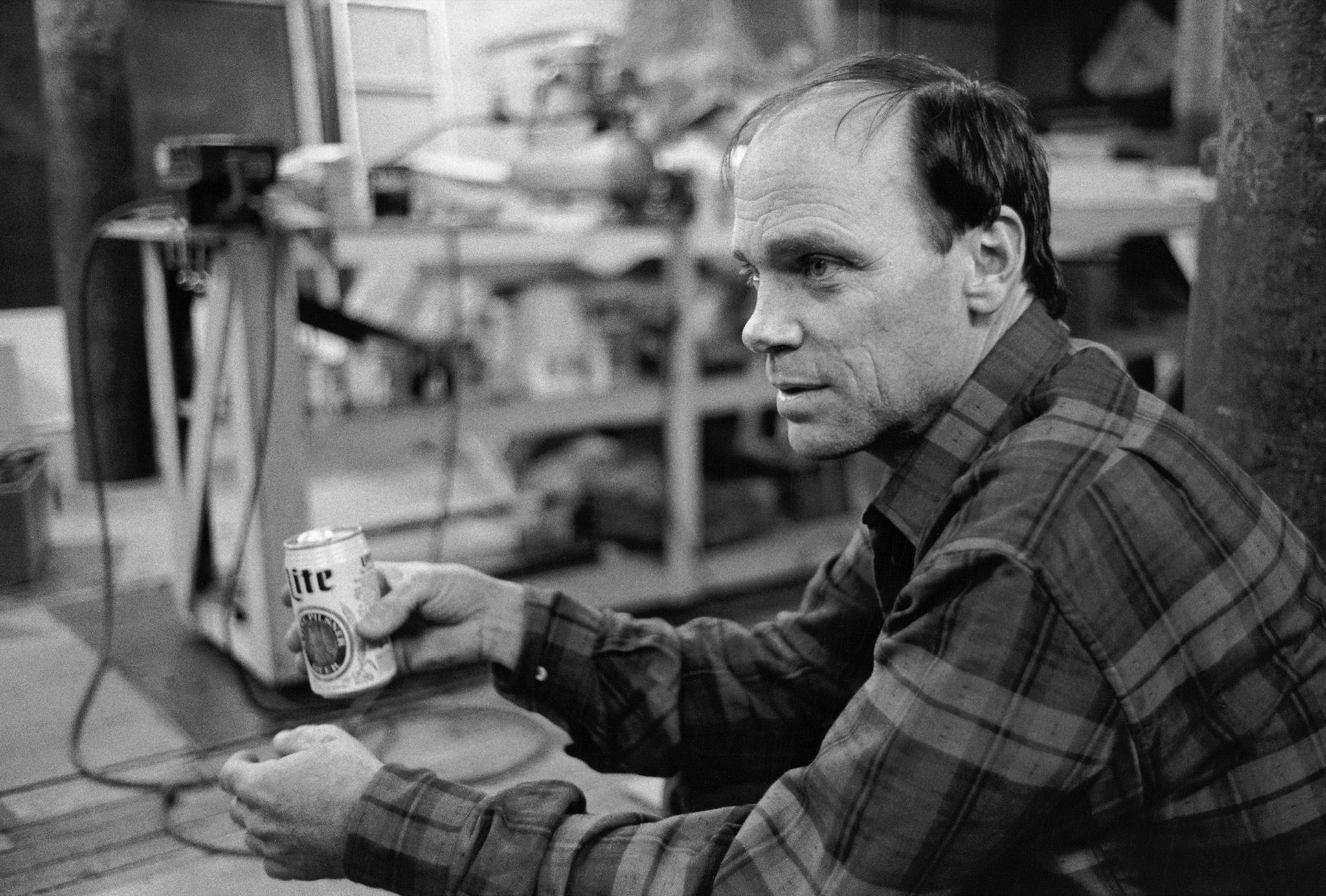

SER SERPAS is the heir of various memories that physically materialize as paintings and sculptures. The artist paints fleshy fragments of ex-friends and lovers and utilizes discarded objects that strangers abandoned on the street for her assembled sculptures, sourcing her materials in an almost anthropological way. Although these former friends and lovers are not physically dead, they might be to a certain extent, as they have left Serpas’s life, who now uses their traces she collected when the relationship still existed — when they were still alive — for her woks. Unlike Derrida, she doesn’t mourn them but rather reminisces in a #moody manner.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: Archives must play a crucial role in your practice, considering that your mom used all these legal and archival documents for her work for the LAPD. Would you describe your practice as an archival practice, or are archives rather tools for you?

SER SERPAS: Archives are tools for me. Now, my practice is not that researched-based. Besides working with my own ephemera, such as photos, I use other people's things for most of my large-scale sculptures. This practice relates to the act of observing. As a kid, I always observed what my mom was doing, who archived evidence for the LAPD for a few years. She often told me stories about that — I saw crazy things, even actual evidence lockers.

CKE: If your practice is currently not research-based, what is it based on?

SS: It's definitely based on observations. I’ve always had a somewhat auto-practice. The way I work with composition and space is similar to an internalized choreography. I don't know how to do underpainting, for example. I just build up paint to the point where it starts to be recognizable. It's not based on any technique, as I’ve never taken a painting class. I surely picked up on things over time, but the process of how a work of mine materializes happens in the moment.

I'm currently doing a residency in Paris for six months. It’s a chance for me to slow down, read a book, and perhaps think about working differently. In the past, I've gone from “innovation” to “innovation” and was working with new materials each time. When I was in college, I used to be an expert on things. I wasn't an artist yet. Being an artist doesn’t necessarily erase your expertise, but if you get too much into a routine, it might. I don't feel dumbed down by what I'm doing — but it wouldn't hurt to spend a month just reading and researching rather than making.

CKE: What were you an expert on in college?

SS: I used to be a community organizer in high school. I was mainly concerned with the school-to-prison-pipeline and worked mostly with queer students and student with disabilities. When I got into college, I started working in fashion and art, and I got swept up in that. I haven't really done any political work since. There’s positives and negatives to that. It feels like I went into a different way of working and thinking, because I didn't interact with people as much anymore.

CKE: So, political work for you implies that you're directly interacting with people and able to immediately see you’re helping them. In a way, your practice could be perceived as political, too. Or is it intentionally non-political?

SS: It's not intentionally non-political. Coming from a background of doing very interactive political and work though, my practice, in comparison, is certainly not political to that same extent. When I started making art, it was explicitly non-political. I always said to myself “This is not political, unless you're going to go out and actually help someone in your community.” I was a bit snooty about it and thought that artworks can’t be activism. In the case of some artists, however, there's definitely a form of social practice involved. What I'm doing in terms of building my aesthetics is strictly non-political though. From the beginning on, I've found ways to try to remove myself from what I'm doing, which results in working with other people's things.

CKE: Do you think political art is less valuable political work because it's concurrently concerned with aesthetics?

SS: No. I have a few friends who make works that have an actual impact. I'm a bit out of touch because I’m not where I grew up, in LA. I would have a better grasp on it if I was still in LA. Now I’m in Paris for probably a year, and I’m going to start French classes in two weeks. Then I might have a better idea of what people are doing here.

CKE: You said that you decided to start the residency as a way of moving away from constantly working. I felt like it was still thoughtful and intricate, yet it was too hectic for you?

SS: It’s been a bit hectic. I've been a working artist for maybe five years now, since around 2017, and I've had fantastic experiences. It was thoughtful because I knew what I was doing each time. My family didn’t vacation when I was a kid, so I used to look at work trips as visiting new cities and meeting interesting people. But this year, I checked in and out of about ten hotels over eight months. Finally, I caught something during fashion week here in Paris.

I’m here to learn new ways to work with sculpture that don't involve me, so I don’t have to get flown out every time I’m installing a show. I’m in a transitional stage.

CKE: Do you already have an idea of how that new sculptural practice will look like?

SS: I’m thinking a lot about specific instructions for making the work. I’ve done a comparable project at the former space Truth and Consequences in Geneva. The show happened with the help of my friend, curator Mohamed Almusibli. I made around nine sculptures in cooperation with friends based on instructions that I wrote for them. Then the sculptures were torn apart, and a different group of friends made them again with the same set of instructions — but they were jumbled in the end.

There is a very specific way of writing the instructions and descriptions. I’ve been thinking about trying to adopt this process and surround the sculptures with these word games. I did a similar work for the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” in 2020. I couldn't travel because of Covid, so I set up instructions for collecting objects on the street that I liked, and the result was fab. I'm not trying to get rid of my sculptural practice that involves me more physically, but I want to alleviate the process.

CKE: How do you like Paris? Geneva, LA, and Tbilisi are important cities for you as well I suppose. How does your artistic practice change depending on the city you live in, considering your work employs a city’s discarded objects?

SS: It has always been more about the constraints of a studio space. For example, the space I’m in right now is supposed to be a live-work space, but I can't really work here. In about a year, I want to move back to New York. I hate to always be just a visitor. So here I'll try to learn French and tap myself in. My work changes based on the cities I have access to. I could never make that kind of sculpture in a studio because there is no space. I also don’t really want to drag trash into my studio.

I’m working on being more collaborative here, and pushing myself to take on other mediums and learn from people who are experts on dissimilar fields. I’m planning to do a collaboration with Rafik Greiss, who lives and works in Paris as well. The collaboration will potentially be part of my show at the Swiss Institute in January next year. I'm going to create sculptures on the street, but the work will be in a photo essay format. We're not going to photograph the sculptures themselves though. I'm going to knock them down on the street after I make them, then we’ll take process shots reminiscent of fashion photos. I’m also planning to work on another project in which I do the set design for a theater company in Tbilisi. I’m pushing myself to take on other mediums and learn from people who are experts on dissimilar fields.

CKE: Does the format of fashion photography relate to your jobs in fashion, which you had before becoming a full-time artist? What exactly did you do back then?

SS: I interned at different studios in their PR departments. I also worked for Susanne Bartsch. I archived her collection of garments, which are often unique pieces that designers including Jean Paul Gaultier created especially for her. I also worked for a stylist named Ian Bradley, who is the best boss I’ve ever had, and my last boss before I focused only on art.

Here at my residency, I’m working on a script for a horror movie, which is part of my plan to make more interdisciplinary work.

CKE: Will you produce the script as a film?

SS: Yeah, I want to. Martine Syms beat me to it. It's a horror movie set in an old college — but not an art school. I've been working on it for three years already. It’s about undergrad school in New York, and a bit like Rosemary's Baby.

I grew up with horror movies. My mom and I watched them together when I was a kid. She saw all kinds of crazy stuff at work and say “let's watch The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,”to calm her down with the fake craziness. She also worked in registering and had to deal with sex offenders, pedophiles, rapists, and drug offenders. Watching horror movies was her way of dealing with it. That’s why I love horror and everything gothic — it's what I should be reading. I should read a book on Gothic literature. I need to go to a bookstore today.

There's a great screenwriting program at Columbia University that’s in the back of my head.

CKE: You want to go back to university?

SS: Yes. I want to finish the script, and properly think about what I'm doing. I'm craving structure. I'm 27 years old, and I feel like my return is happening right now. I want to restart myself and get good at something. Something that's not art.

CKE: Why did you not pursue a career in fashion? Could you imagine working in fashion instead of being in the art world?

SS: No, and that’s mostly because all my great friends already do this. What I liked about fashion is that it’s unabashedly a business. It doesn't masquerade as being good for the public or being in the public’s interest. It's like “listen, this is a business, and we have a product that you should buy. We’re selling a fantasy.”

But ultimately, I'm not interested in that. I love to wear it. I love The Row. I love menswear. But I don’t want to have a career in this industry.

CKE: You mainly don’t want to work in fashion because of its extreme business side. Is this an issue you also criticize in the art world, and did you have a different idea of what the art world is like before entering it?

SS: From the beginning, people told me that marginalized artists don't get supported in the same way. Art is definitely a business. Issues can only get better if people become more comfortable with acknowledging them. Then transcendental things might happen. But first, interns need to get paid, and assistants need to get paid, as well — and decently, too.

I went into art knowing that there are different forms of abuse. Although fashion is this reckless business practice, it’s why I started working with clothing and fabrics. I had all these excess garments from assisting stylists and being friends with designers that gave me their weird extra stuff: crazy patterns, faux leather, fur, and all kinds of tchotchkes. I had this body of material to work with for my initial sculptures, and I knew they would look good because they are made of interesting things.

CKE: The garments and found objects you're using for your sculptures used to be other people's things. They belonged to different spaces and beings before you decided to use them for your art. Particularly, when we consider furniture. It used to be part of a person’s home, belonging to an intimate sphere. Do you think the finished artwork that employs these physical intimacies are imbued with the identity of, say, the people that owned them before? Or are the works neutral objects?

SS: They're definitely not neutral. They had past lives. You can see the wear and tear on them. You can see how they were used, and how they were worn down. Then there is the question of why somebody decided to get rid of them? It depends, of course. Some of the things are brand new, and they were thrown out because the person bought a new thing, not because it was in any kind of disrepair. When I was looking for stuff on the streets in Tbilisi, things were literally standing on one leg. But this one-leg-thing is owned by the shopkeeper, and I can't take it. There was also a shift from working with my friends’ things to working with complete strangers’ things.

CKE: When you depict friends in your paintings, do you reminisce about a specific moment in the past, or do you paint in the actual moment?

SS: Nobody who has appeared in my paintings I am still friends with. But I have also never identified them. I mostly paint people that I slept with in the past. I have photos of them that I took while we were together. Then I zoom in on the iPhone photo while listening to music, try to get the detail right, and paint. That’s the closest I am to working with my own garbage.

CKE: Do you sometimes regret painting people you’re not friends with anymore? Since the painting that evolves out of this past relationship is a physical reminder of a person who doesn’t exist in your life anymore.

SS: When I start the painting, I’m already not friends with any of them. From then on, I have a sentiment of “you wasted my time, so I’m just going to look at this photo for a bit more.” That's also why I've never painted any identifying features of anyone. I’m not using these people as models. I’m just trying to get the flesh tones as correctly as possible. Then there are moments of juncture where there is a bit of my arm on someone else's leg.

I'm not a portraitist. When I work on a painting, I think of it as a landscape. I also think about how I crop the photos, and how to paint the gradual changes of skin tones. My first paintings were two-dimensional and cartoonish. My studio and housemate at the time, Hannah Black, said “If you're having a hard time with this one, why don’t you just paint something that you can bear to look at for more than a few minutes?” And then I thought to myself “Well, I have all these #moody Instagram photos that I didn't post from college. I could look at these.” I started painting from those and kept doing it. I don’t have an infinite supply of photos, however — I’m running out. But I also won’t have sex with 100 people and tell them “Let me take some moody photos.”

CKE: Has anyone ever recognized themself?

SS: No. I purposely don't paint tattoos or faces. Nothing is identifiable. Even features sometimes change when you paint them. Things morph, which is fun.

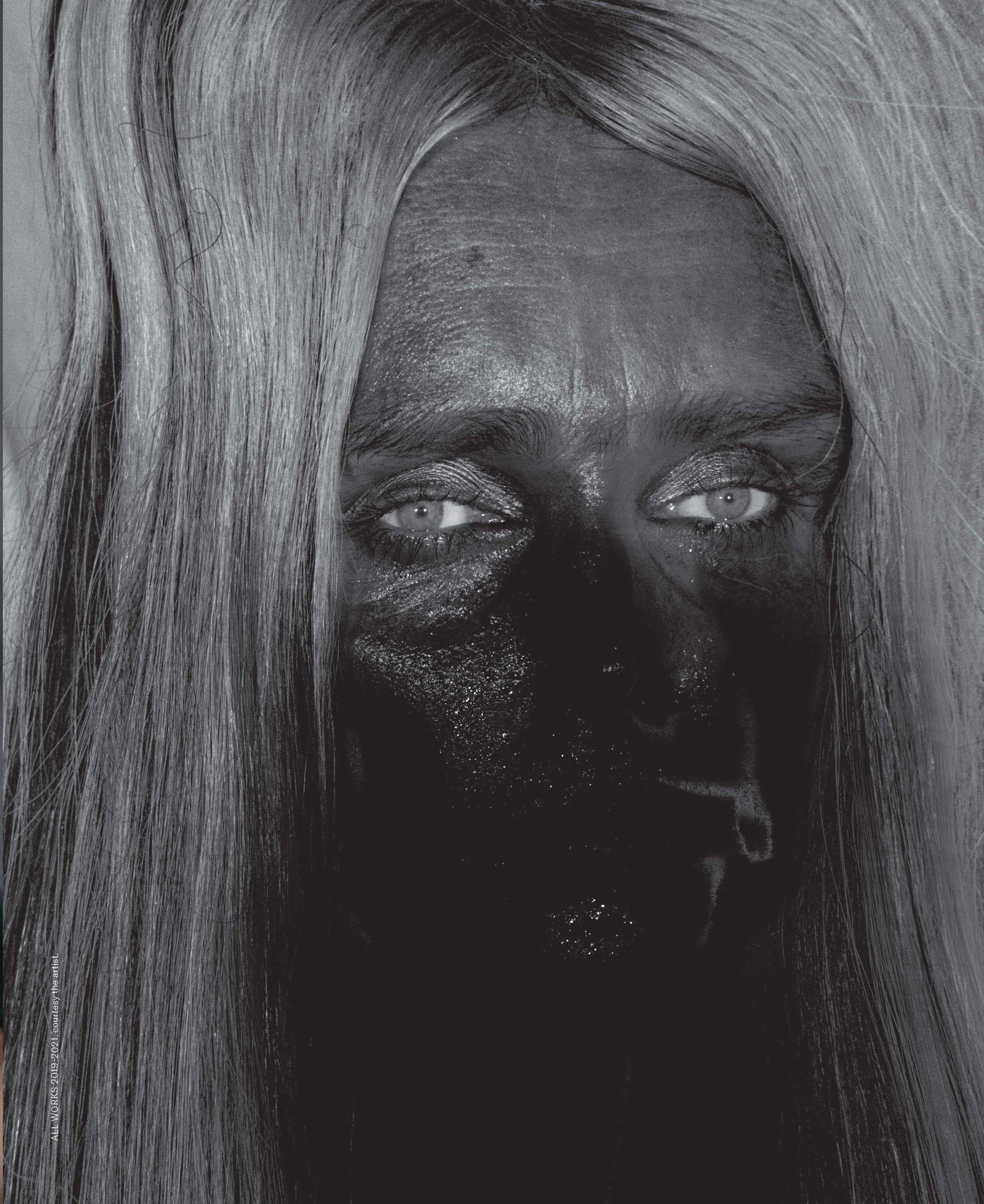

CKE: Identity seems to always be concealed in your work. Could you imagine creating work that explicitly deals with identity, for example, the identity of the person who owned the couch before you placed it in a gallery, or the identity of the person you painted, or perhaps your own identity?

SS: At this moment, I don't have any plans for that. I want my work to be striking and intense in a formal way. I want to have complete control over it. There’re still some things I want to figure out before I'm ready to disclose anything. But run into me at a party at 4am, and I’ll disclose all kinds of things.

Credits

- Interview: CLAIRE KORON ELAT

Related Content

ALEXANDRA BIRCKEN: Bodyrevolt

MICHAEL HEIZER: Desert City

Dark Matter: ANDRO WEKUA

Maintenance of Curiosity: OANA STĂNESCU

Where Walls Float and Hearts Are Garbage: FELIX BURRICHTER’s BLOW UP

GRUPPE Wants to Haunt and Heal You

MATTHEW BARNEY’s Spiritualism of Death and Rebirth

STEPHEN BAYLEY on CRASHED CARS and the DEATH OF THE MODERN ERA