The Undercurrents of Materials: CUDELICE BRAZELTON IV

To see the present through a universal gaze, you might have to consider history and all traditions that preceded—without being a traditionalist. The present and future have to be built on something new that is not a repetition of what was previously there. It is a way of deconstructing history to construct the present and futurity.

Cudelice Brazelton IV’s practice revolves around acts of deconstruction and reconstruction. He dismantles garment structures to build architectural sculptures—which consist of leather, denim, or rubber, for example—and often uses found materials that are decontextualized in the exhibited work. While his paintings, sculptures, and installations, which end up merging together to become one medium, challenge inherent prejudices that influence perception, they also pose the question how you might deconstruct your own gaze to attain a different form of looking.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: Are you proposing an alternative way of seeing with the help of your artworks?

CUDELICE BRAZELTON IV: I want to complicate the ways of seeing. To speak in a very visual way, I’m trying to make work that represents flashes of a train passing, and then there’s someone moving past me in that point of view. These are simple examples of collision. The practice intends to open up different aspects of how subcultural interests shape the peripheral awareness. It almost seems like a clouding of perspective while one moves through different infrastructures. That’s why I stand by assemblage—as a way to reflect on those psychic frequencies of a shifting environment on the body. Self-expression? Nothing is fixed here, and I want to keep it that way.

CKE: I read that you’re specifically interested in the residue of urban space, which is tied to the everyday architecture of such a space. The architectural dimension is important to consider because it’s a physical structure that builds and endorses social power systems.

CB: When a space is empty, it’s dormant, but it still has an energy from past events or previous activities. This residue is always present. I think you can also clearly see that in the works; there are architectural scars that I’ve been leaving over the past few years. I’m carving the space, and I’m learning through the fabric. At the same time, it’s causing something of a “flickering flare.” If I were to relate it to existing power systems in architecture, in many cases within exhibition spaces, I would like to focus on a type of shedding that is often excluded and ephemeral.

CKE: Do you mainly use found materials from such urban spaces?

CB: Yes, I use a lot of found materials. For me, it doesn’t matter if it’s an electronic device or something discarded on the street. There are all kinds of different materialities. But they come from a similarly developed aesthetic, which I find pretty; it’s individual but also universal. It’s a magnetic feeling when you come across objects that are really interesting. Nowadays, found objects or materials are often used but are too conscious of documentation images, of the staging. I hope the physical encounter with the found material also hits the viewer on a phenomenal level. Otherwise, it’s boring.

CKE: Is there a specific place you get the materials from, such as junkyards? You now live in Frankfurt, is this where you mainly get your materials? Or is it from all over the world?

CB: It’s scattered all over. There are certain areas that I really enjoy getting materials from. I’m often creating a situation in the context, and then I realize that’s the material I’m going to use. It’s a feeling that has to be nurtured while looking for something, and there are certain guidelines and strategies. In a work titled Bricoleur (2022), I use an old industrial sewing machine that is shaped like a shoe and has an engraved brand name on top of it. It was so strange to look at it and not be quite sure what it is—it almost seemed augmented. I was looking for this object, and I had to dig so deep into these communities where the sewing machine is used and had to ask very specific questions. That was really fulfilling. I’m interested in collecting and manipulating these objects. How they are incorporated in the work isn’t so far off from its intended function. They are somewhat clumsily used, which feels honest.

CKE: It’s like found materials have past lives—similar to what you were saying about empty spaces that are charged with past energies. Is the life the object had before important for you?

CB: I have an interaction with it, but it still has its own type of autonomy. There is an exchange I try to have, but not like a metaphysical agreement. There are lot of objects where I’m not feeling that strange interaction or these clues, signs. So, I won’t use that object at that time. It’s very situational. I also travel around with materials—sometimes they’re sporadically placed in my suitcase. When I then open it, some objects are magnetized together. That’s a sign to me that these materials are attracted to each other; there’s some kind of chemistry, which is a very organic approach.

CKE: Many of the materials you use, including leather, denim, and other textiles, are materials out of which you can also make garments.

CB: Right, I think my use of textile is interested in the situational as well as a particular kind of drape. Leather and denim feel like basic colors for the body. Yet, it can be defined in so many ways. That malleability is cool because one detail of a crease, a fold, or a tear is all it takes to signify. We see that word often, right? I mean the word as in pointing towards or through. Physically or metaphorically. Self-defense or an instrument to map? Patterns, texture, and weight of fabrics are fun to subtly work with and try to get into the static effect.

CKE: When I saw your work for the first time, I was interested in the materials. For example, you stretched leather over a canvas in one work, and the leather suddenly had a sculptural sense to it. The works appeared like deconstructed garments, without you taking a garment and deconstructing it.

CB: There is a technology behind every garment. The deconstructing comes mostly from accessible craft habits I have, and whatever technology I find in the material will respond to those habits. That sounds like a complicated way to say something else, but I think a system is built with painting, sculpture, sound, and site-specific models. Define it how you want. But that becomes a personal technology and that should be cared for. And having exchanges with other ideologies and systems that want some kind progress. Maybe I am interested in that further dimension between flesh, textile, and technology, and how that can extend in space.

CKE: I think fabrics can be considered as archives—just like objects or spaces.

CB: Yes. It’s always an ongoing process with such objects. I make these works in varying sizes that have burn marks on them, and the scent is still there. It’s as if the burns act like banners or flags. So, collecting these things is not only physical.

The undercurrent in a material is my main driving force. It’s not just about the stationary aspect of how things sit in space or what their function is. There’s so much activity that is waiting/dormant at the same time. It’s a very subjective act, perceiving and further treating a material.

CKE: Subjectively perceiving fabrics or a garment relates to complicating the act of seeing because seeing is obviously completely subjective. There can’t be one way of how you see an artwork, for example. And there are many different gazes that you have to take into account.

CB: A lot of what ends up in my works shows up in my daily life. There’s always this kind of consciousness of what is needed at the time, and how you can shift your gaze to meet the other gaze. My work represents a mix of different interests, for example, my interest in cosmetics, specifically Black styling. I was raised around that, as my mom and grandmother were hairstylists. In Totem (2020), for example, you have a large, basically homemade, clay piercing that looks like a relaxed dreadlock or needle hanging from the ceiling. The exposed screw at the tip meets the viewer around a common eye level, causing that confrontation. Trust me, looking is considered. We all should consider, even if it’s unavoidable.

CKE: What do you think about white people who wear dreads or cornrows? I think it’s ridiculous, not only because it shows a great cultural insensitivity but also because it simply looks stupid.

CB: Oh, people can do whatever they want, just don’t expect to have that unspoken acknowledgement for them that Black folks give each other. I think that is the richest part. Oh well.

CKE: You grew up in the US and then moved to Frankfurt, right?

CB: Yes. As an American person, Frankfurt felt kind of familiar because of the skyline. I was following the American discourse at the time, around six to seven years ago, which was super specific about identity. I mean, next level. Back then—and still today—a lot of people said that as a Black artist, you have to make a certain type of Black work. The scope has improved and expectations are less in terms of medium and subject matter, but the subliminal shit has amplified I think. I wasn’t trying to get away from that, but that kind of discourse had its own set of problems. It’s naïve to think that it would be totally different here. Germany obviously has its own variation of the same issue.

Since I was born in Dallas, Texas, I have a connection to a Southern Gothic that is there. Someone special recently gave me this publication To Live in the South, One Has to Be a Scar Lover from the space 1646 in The Hague. Reading it felt like a reminder since I’ve been away. There is a haunting sensibility, but full of spirit and durability. So, how does that respond to the histories around the haunting sphere here in Germany or abroad? I’m blending these interests and experiences to make something strange.

CKE: I think this all leads back to the notion of gazes. Someone who grew up in Europe will have a totally different gaze from someone who grew up in the US. And I think there is also a discourse here that artists who are specifically concerned with racial issues in the US are not so tangible for a German audience because racism in the US very much differs from the one here.

CB: The methods that I’m trying to focus on are understood by a lot of people. The drive was coming from an experience that is my own, yet it is accessible. It is translating in many different places and somehow it can be a short bonding moment or an intense response. For example, someone told me that this cut out printed image of a dog’s lower jaw reminds them of the color of the gums of some people of color. When I heard that, it sparked that unspoken thing that you felt was your own insecurity. Politics, image, and body are wild, right?

Everybody knows what a razor blade looks like, and what it’s used for. But when it’s turned to a kind of node on the wall, like a non-electronic object simulating that through simply making it look like something with multiple factors, it ends up being in-between interests and images.

CKE: So, are you proposing a universal gaze?

CB: Perhaps the universal gaze would be the moment when an incident happens when you’re in a crowd of people and everybody ends up responding at the same time and in a similar manner. I think that‘s the universal gaze. But a gaze is always a longer situation than just a reaction. So, a universal gaze is something you have to keep working on.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat

Related Content

Other People: SER SERPAS

“Scrapbooks 1969 – 1985” by Walter Pfeiffer

The American Dream Doesn’t Exist, It Never Has

“DEVILS ON HORSEBACK” Curated by Claire Koron Elat and Shelly Reich

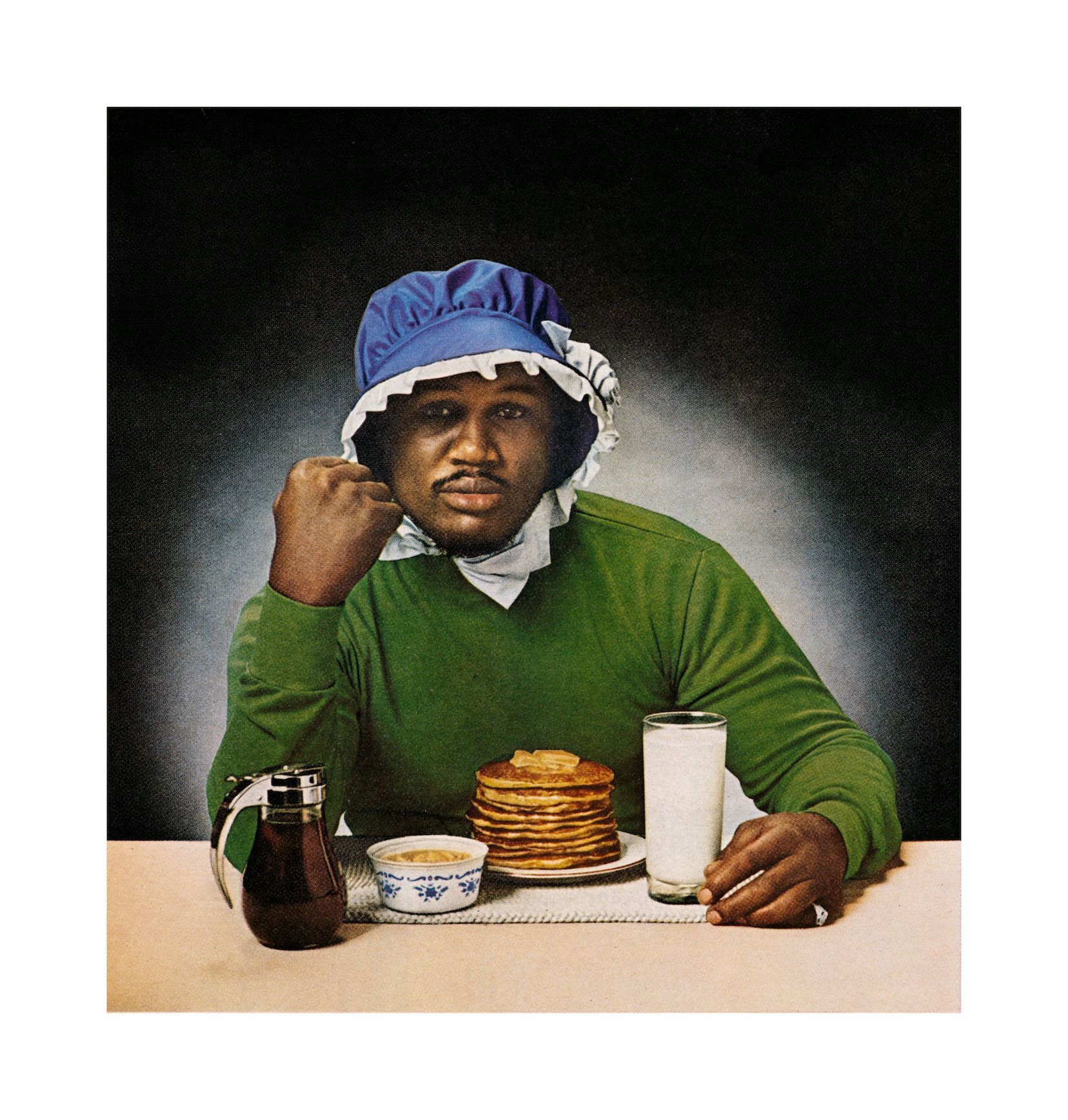

“It’s Important to Be Visionary Rather Than Reactionary”: Artist Hank Willis Thomas’s Aesthetics of Mass Action

MARTINE SYMS: Set Alight All Hackneyed Tropes

ARIA DEAN Life World

On Power, Picasso, and American People: An Interview with FAITH RINGGOLD