LOUIS FRATINO Paints Gay Intimacies

|Hugo Bausch Belbachir

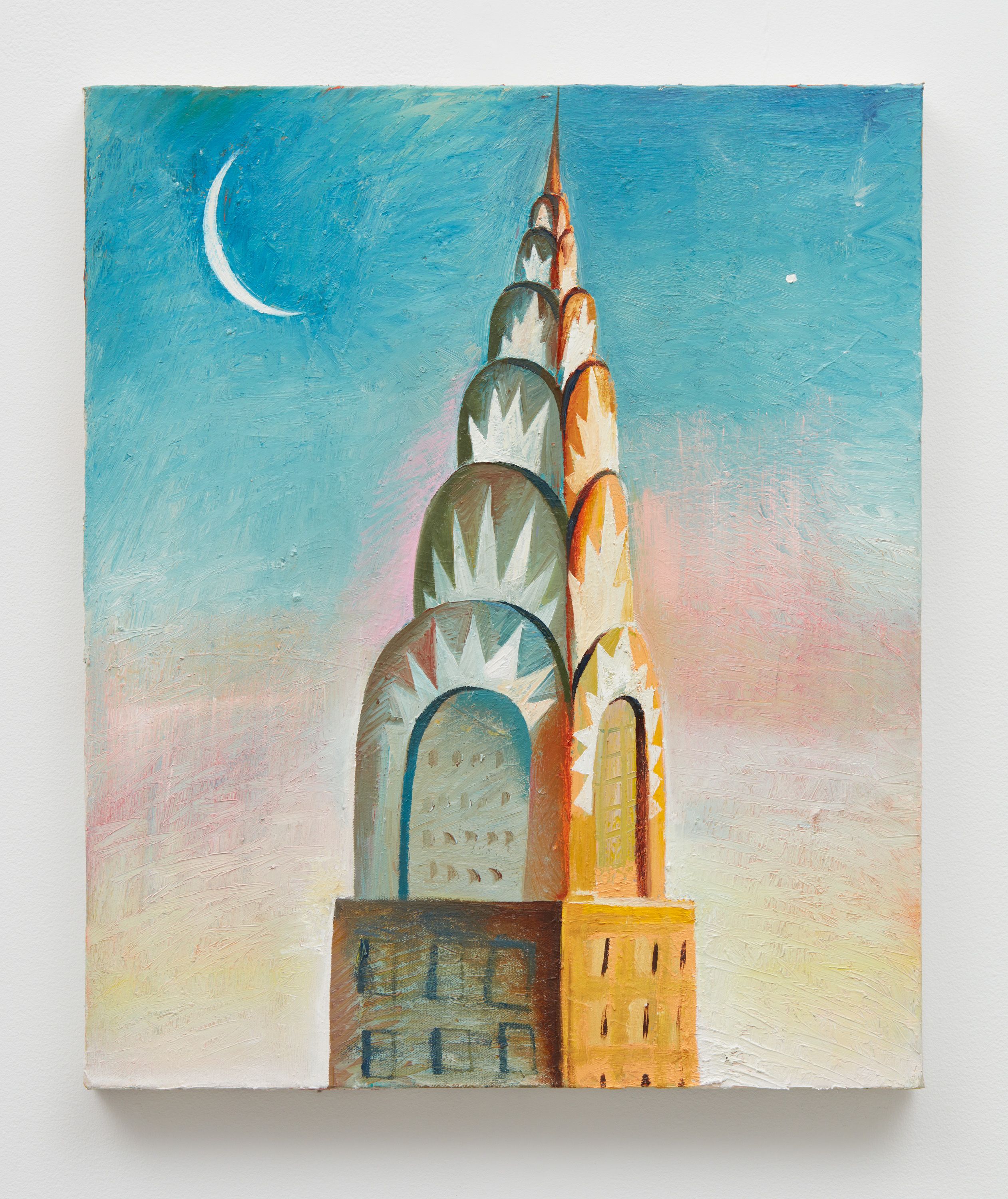

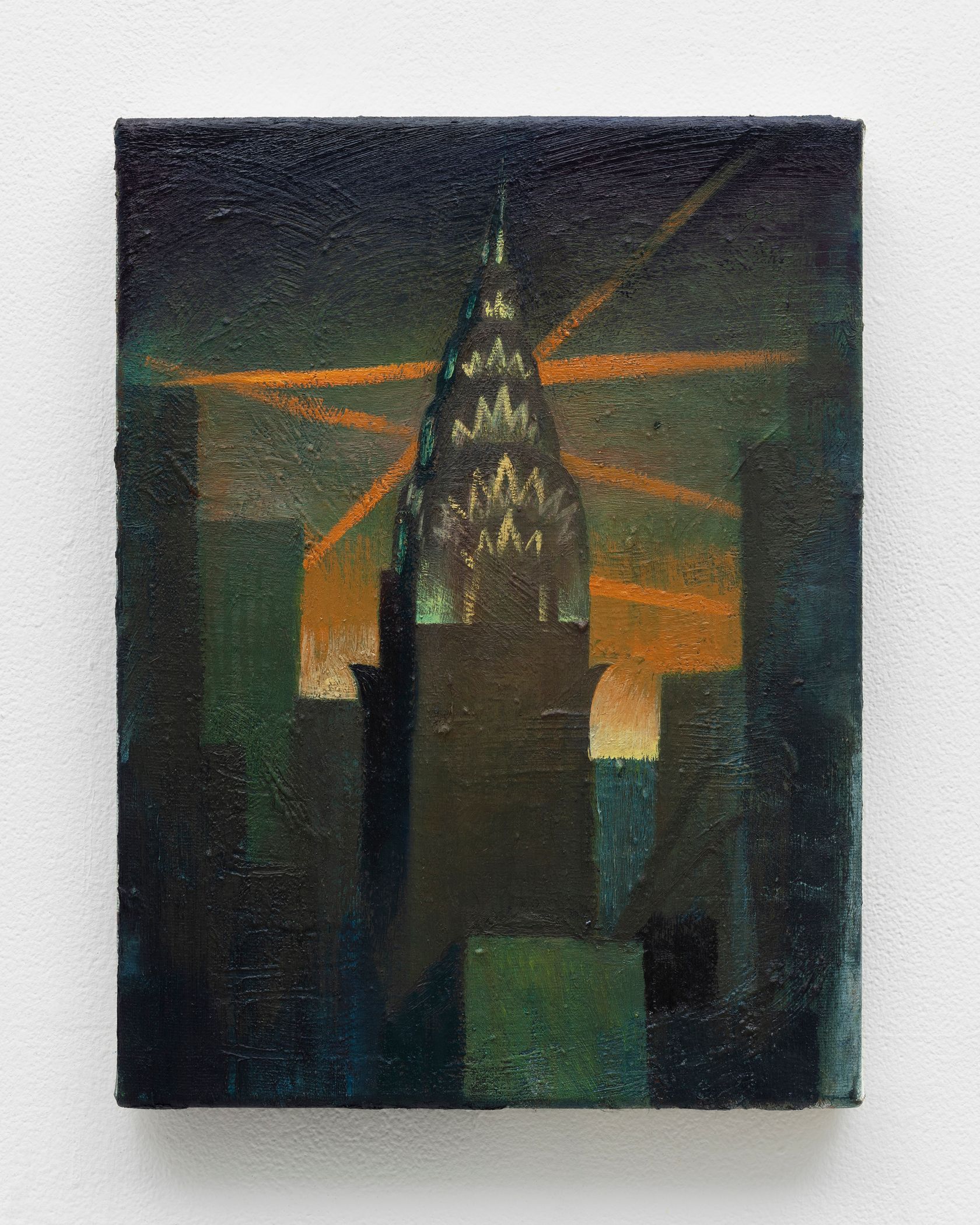

There is a single tension in Louis Fratino’s paintings, a common one; a dreamed presence, a moment imagined and distracted, sighed. It’s a hand that embraces another, a hand that lets itself be used. A belly that bends over the back of another, that wraps itself with it, in a bed, a warm bed. It’s a secret, a discreet comedy; a preserved, cherished moment that we devour knowing it is perishable, but wishing it to last a little longer. It’s an erotic distraction, visible in the details of an open window on the sea, on the river of the city. It’s the precise moment extracted from the whole; an amorous abstraction, in steps outside of the outside. Gardens invented by Matisse, landscapes profaned by Pasolini, figures that met Hockney in a building painted by O’Keefe.

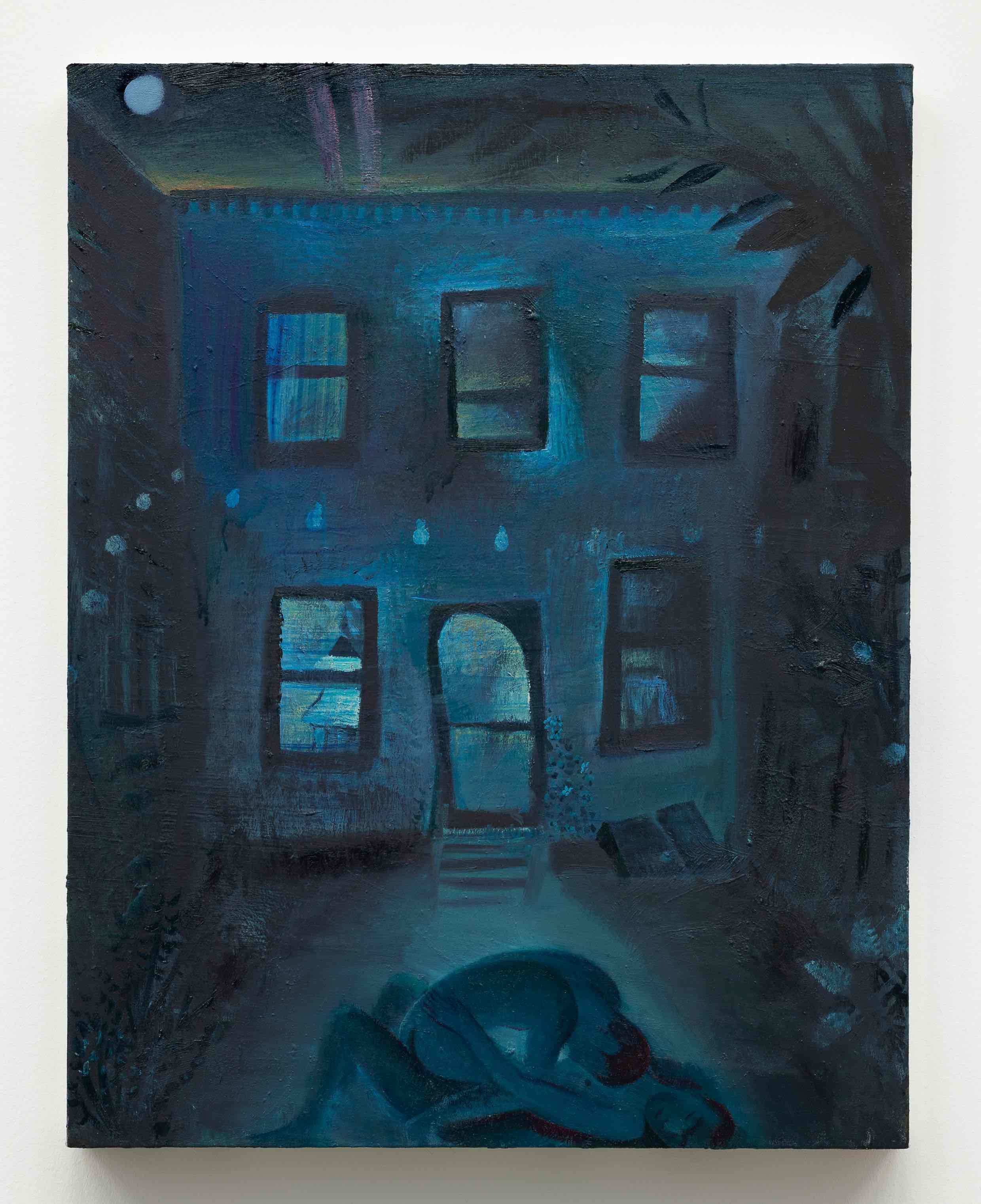

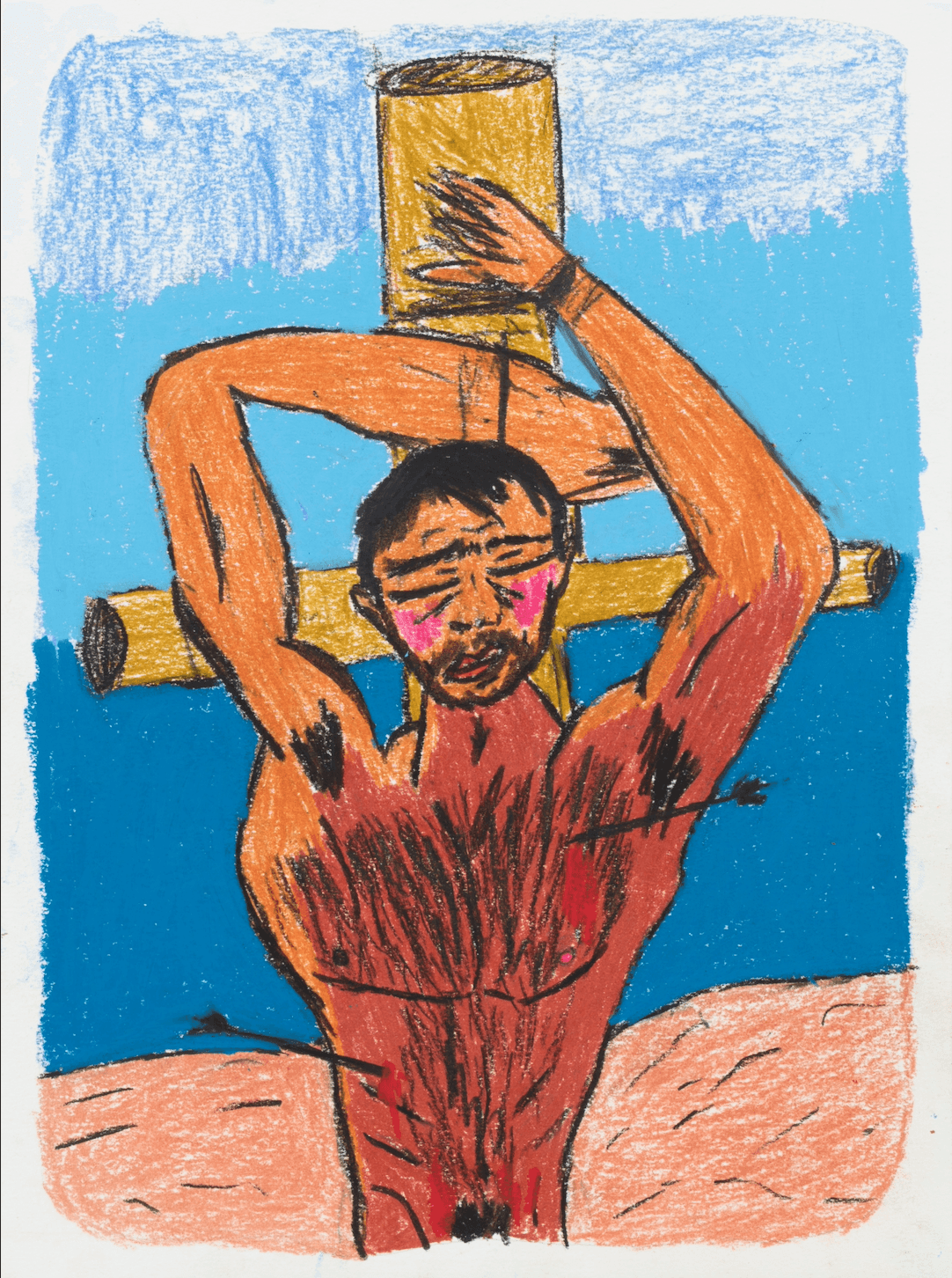

It’s lovers. In In the night garden (2020), time is insufficient; two men are fucking outside a townhouse, in a blue garden. One, bent over the other, carries a circle of light that has formed between the two men’s stomachs. They are fucking on the ground, on the dirt path that leads to the house. The other has his eyes closed, he sighs, moans with his mouth open. Maybe they are making love for the last time. Maybe they would not have known how to wait, could not have. Louis Fratino poses his glance here, then draws.

Over the past five years, Louis Fratino (b. 1993) has developed a body of work that interrogates the political potential of queer desires. Drawing on his personal memories and references, Fratino combines a visual history of queer languages, from Italian political cinema to turn-of-the-century modern painting, forming a framework filled with landscapes, bodies, and interiors whose eroticism is a gesture for self-discovery.

HUGO BAUSCH BELBACHIR: Where are you now?

LOUIS FRATINO: I’m in East Williamsburg in Brooklyn, New York.

HBB: You received a BFA in Painting from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore with a concentration in illustration. Can you tell me more about your practice during these years of study, and how they shaped your interest in figurative representations?

LF: I didn’t have a lot of information about the lives of working artists or expectations that I could be one of them—so I was studying painting but also studying pattern-making and book illustration thinking that those might be potentially more practical career paths. But my interest in illustration extends far beyond the practical. As a young person, I was totally absorbed in the world of drawing in children’s book images via the work of Lane Smith, Maurice Sendak, Ruth Chrisman Gannett, and John Bauer. These are only several of the many illustrators that have profoundly influenced my sense of style. At the Maryland Institute College of Art, I was in the formidable hands of Jo Smail and Ken Tisa who encouraged me to follow my interests in drawing from memory which was the starting point of my mature body of work. Working from memory was a critical shift as it allowed me to consciously and subconsciously fold these very early influences from children’s book imagery into my work.

HBB: In your process, drawing comes first, with all its subconsciousness. Could you tell me about this moment, and how it establishes concepts of diaries? How long does it take you to draw before painting—to apprehend the act of painting?

LF: One of the primary qualities of drawing is that its logic surprises the artist with its own strange and independent wisdom. Since drawing is a mode of thought, it is also surprisingly unselfconscious, just like thoughts we may choose not to share. Allowing myself to draw often in the studio is a way to understand what subjects, for better or worse, are at the front of my mind. In this way, drawing becomes automatically autobiographical or diaristic, like all obsessions. Drawing is immediate and can happen in under a minute but can also take days or weeks if they are larger pastels. I am most interested in the drawing that happens very quickly—that does not even want to be beautiful but has a kind of necessity to be put onto the page.

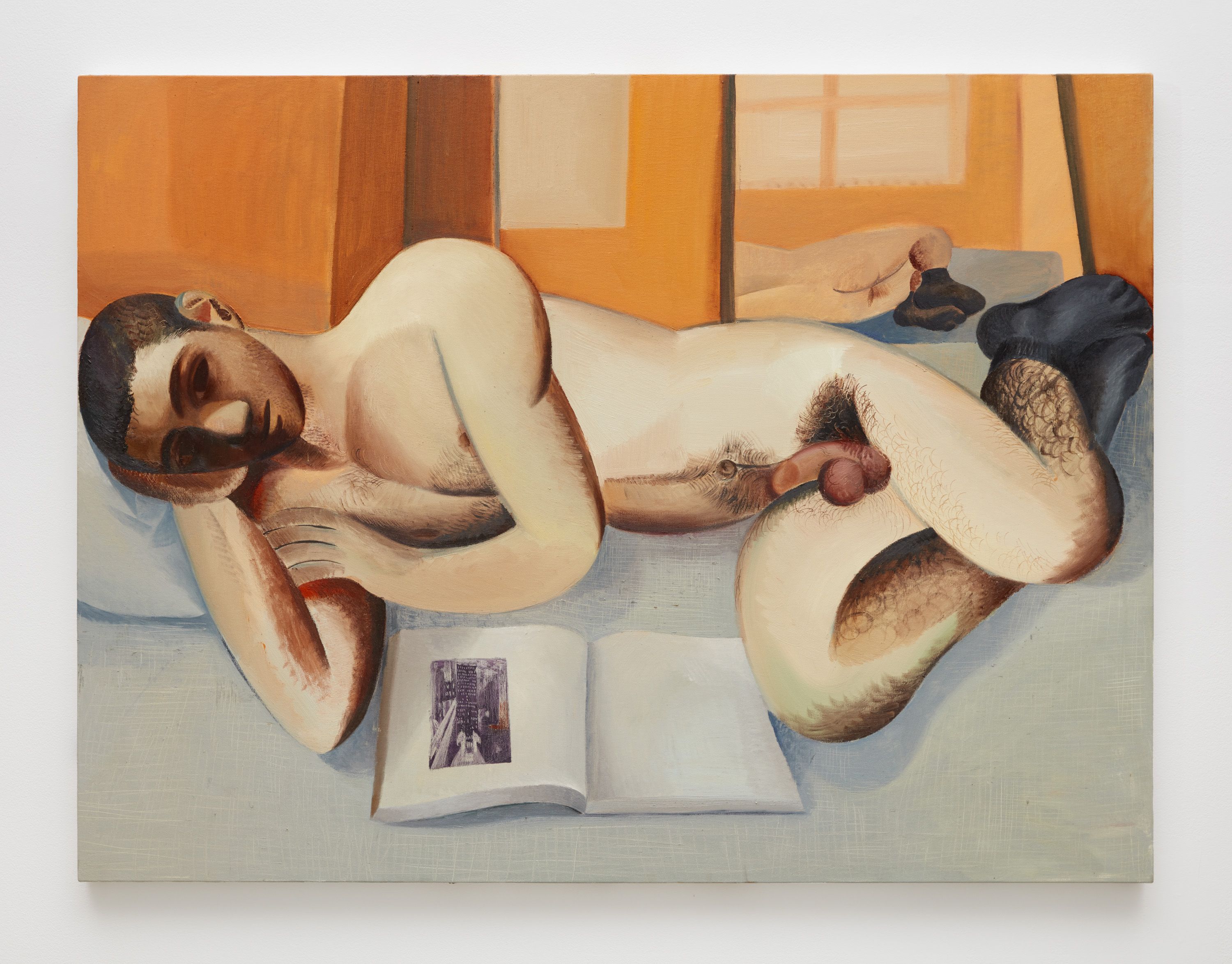

HBB: Your work is mostly focused on being a grammar; it conceptualizes itself from its references and materials, quoting Modern American and European paintings. In Man. Book. Mirror (2020), a man, almost naked—he is wearing only a pair of socks—is lying in a warm interior, surrounded by orange sun walls. His head, resting on his hand, does not move when interrupted by our presence; only his eyes move toward us. He is reading a book, which shows an early painting by Georgia O’Keeffe, Radiator Building— Night. New York (1927). This is a first reference to the visual structure of Reclining Nude (1957) by Yannis Tsarouchis, the Greek gay painting figure. What is your relationship with artistic figures, and how do they find their way into your work?

LF: I believe that looking at painting is to learn how to paint, so I consume a lot of art history through my own research which is more of an indulgence than a study. I also think that the idea of copying art history is an intelligent one, so I resort to it frequently to begin paintings. I probably favor artists such as Yannis Tsarouchis whose subjects are outwardly queer, because I am curious about the things I may learn about myself the way I would when meeting a queer person from another generation. The things I choose to paint are more or less images I respond to at an emotional and physical level, and that I simply am attracted to. The periods of history that I reference are not limited to the 20th century, as I also make work with origins in the classical. I like to think of a queer perspective that also belongs to the distant past. I am excited by the notion that people belong to atemporal families and that art making and viewing is an opportunity for us to dialogue in a physical way with people whom we otherwise couldn’t interact with. For me, this includes the erotic, the amorous, or the devotional. I remember working at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore and what I loved more than all the objects there was a single tiny sandal found in an Egyptian tomb that still had the impression of a tiny foot on its leather sole. I think that allowing art history into the work is a way of rubbing up against these kinds of impressions.

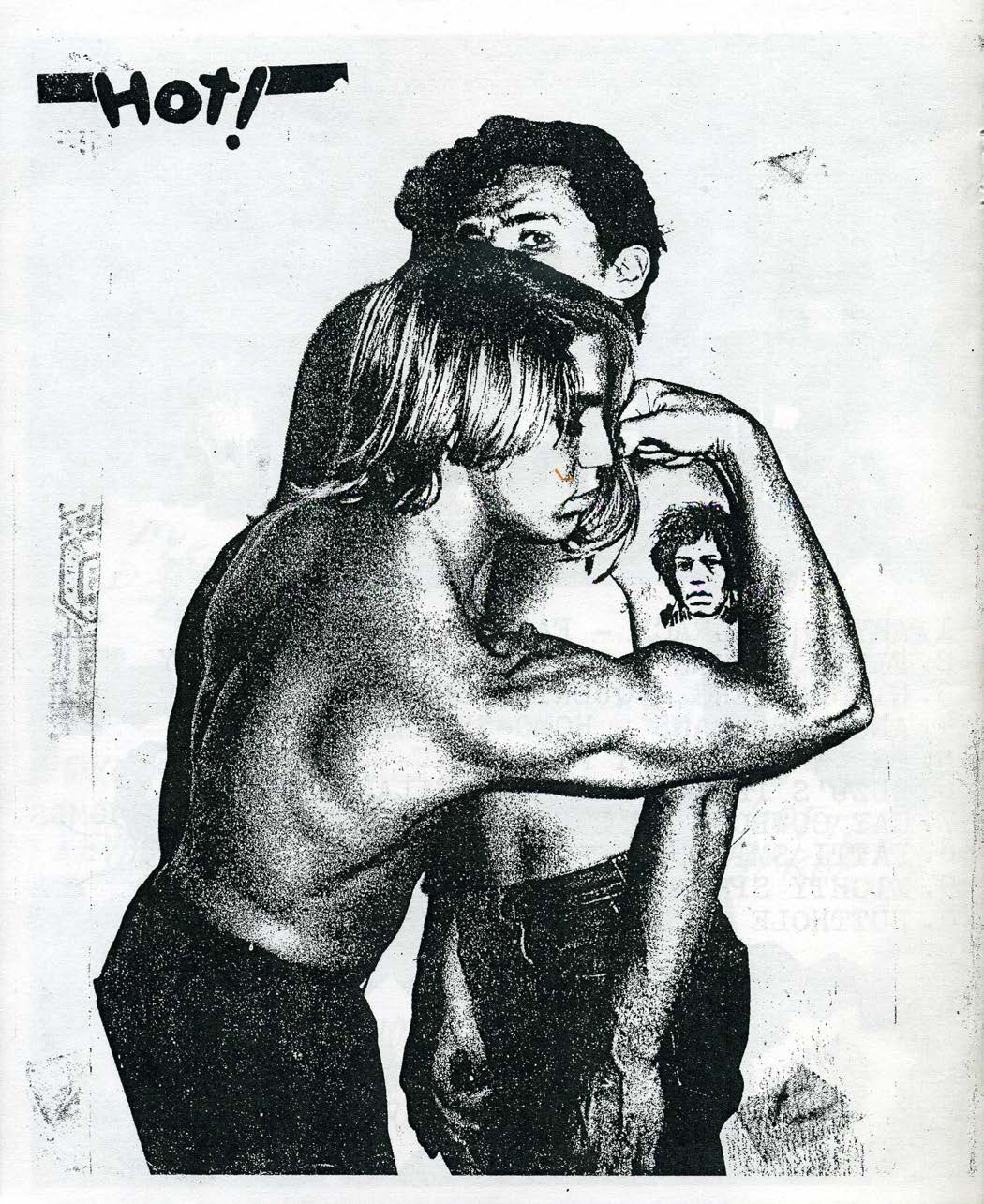

HBB: I guess it's also a way of asking ourselves what belongs to us, in all its intimacy, in all that it says about the reflection it carries on us, on our bodies, on our desires as gay, queer people. An important figure in your work is also Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose image from Il Decameron (1971) you suggest in A Breeze (2017).

LF: Pasolini is a good example of an artist who was also looking for a queer perspective in the classical. Il Decameron is a film that interprets Boccaccio’s ten allegorical and raunchy tales from the 14th century. I feel a kinship with Pasolini’s passion and irreverence for art history and his unselfconscious use of it as a springboard for an artwork. Pasolini exalts the contemporary and bawdy nature of Boccaccio’s stories, bringing their eternal relevance to the forefront. I also admire Pasolini’s depictions of sex which are never crass or sentimental but feel true in their tenderness and terror. I think Pasolini’s perspective on queer identity is one I subscribe to, which I also find in Paolo Mieli, which is the idea that queerness is a universal trait. Pasolini’s Comizi d’amore (1965) proves this to me. He demonstrates his interest in sexual liberation that extends beyond queer people to the whole world. I am interested in filmmakers and painters as equal sources of inspiration.

HBB: Your work does not pretend to create images but makes them submerge from our memories. Vague, imprecise, reminiscent moments. What place do you give to your own memories? Your early paintings are often representing moments of intimate lives, of family, of friends.

LF: I am interested in memory as a subject, and often the paintings feel more like the residue of memory, than a representation of an event. I am not suspicious of memory’s inability to stick to the facts, instead, I find these failings and fantasizations to be legitimate facets of our personhood and lived experience. I am curious about why I enlarge or diminish particular things in memory, and why some stick and others slip away. I think painting has always been a struggle against the fading nature of memory, and so this is a universal subject for anyone who paints. My attraction to representing the things I love, have loved, or want to love comes from a belief that painting has the power as “living” images to alter our experiences of the real world. Letting memory out of the cage of facts allows for a kind of associative thinking that folds art history into my own experience—my bed and Yannis Tsarouchis’ bed, his toe, and Pasolini’s toe. My acquiescent relationship to the false or exaggerated aspects of my memory comes from the belief that painting can only struggle against impermanence, and never conquer it. I think my paintings can be interpreted as an illustration of that.

HBB: I would also like to talk about Picasso and the importance of his vocabulary in your work. You speak of him not as a figure but as a grammar.

LF: Picasso and the figureheads of modernism introduced a new canon of visual codes that tell the general public that they are looking at an artwork. In this way, Picasso is not just a stylist or an individual, but a grammatical structure in the language of painting that anyone in the world can identify. I think that what happened to painting after Cubism was obviously so seismic that anything happening in the Western world afterward had to be for or against it. I think my position on this kind of grammar is that its legibility and ability to speak to a large public gives my politics an advantage—for example, when a depiction of something such as homosexual sex, which has historically been thought of as clandestine or criminal, is represented in a language that is very legible, the way the world relates to it as an image can change.

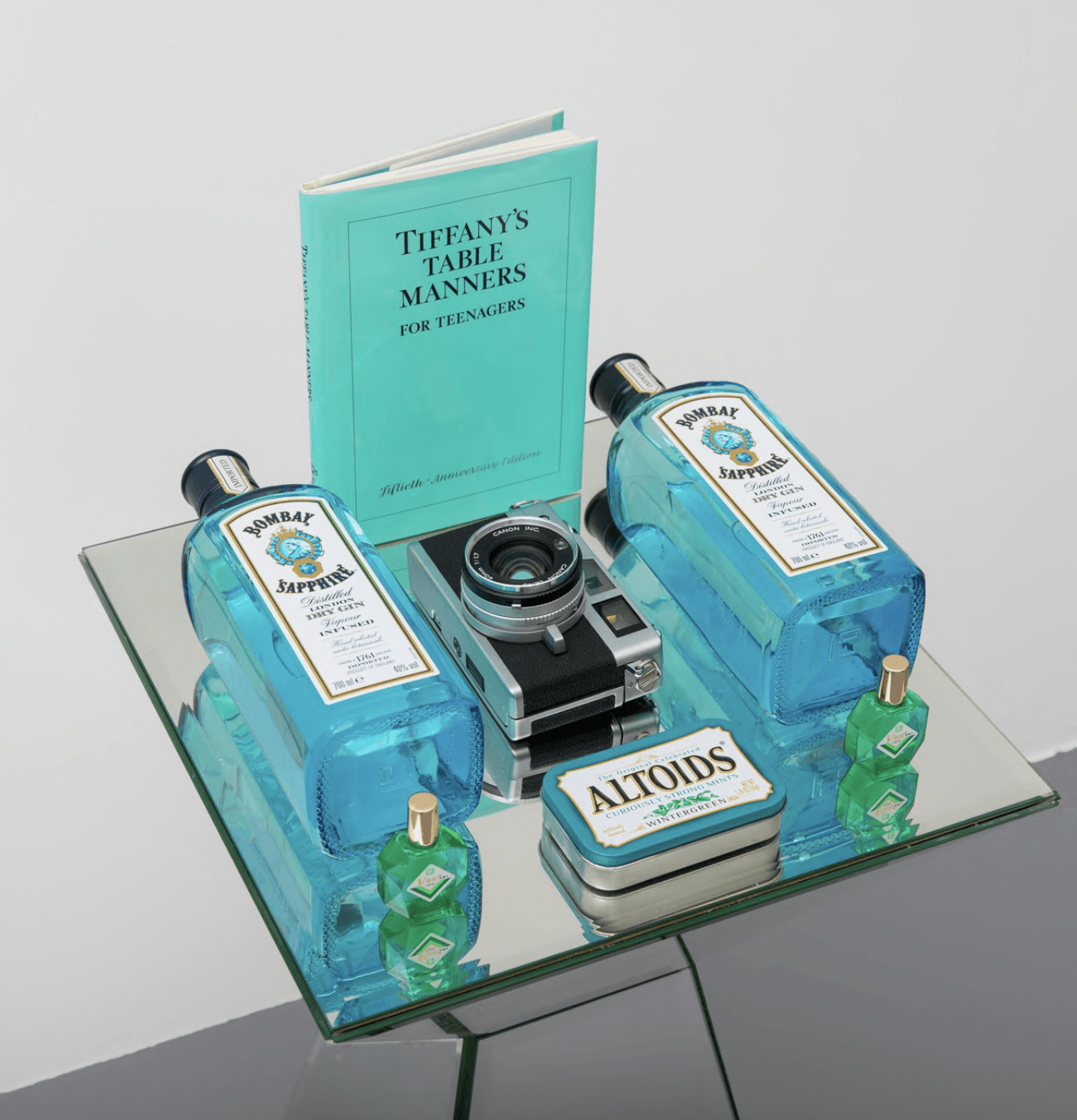

HBB: You have also recently developed a set of sculptural pieces with which your work of entanglement of bodies takes on a more precisely corporeal meaning—focusing on locating bodies as adjacent to our own, moving in a mutual space, displaced from the intimate frames in which they were conjugated in your paintings.

LF: Sculpture is really difficult! It belongs even more to our world than paintings and has to follow laws of gravity, engineering, and space. When I first went to Albisola to make a body of ceramic work, I was interested in pushing my practice into new material in the same way as when I am trying new printmaking methods or animations. Surprisingly, the thing I ended up doing was making bas-relief sculptures that didn’t necessarily do anything separate from my painting but reinforced how I think about painting sculpturally. A lot of my work is very volumetric and happens in a shallow space, like a trompe l’oeil bas-relief. Working in ceramic opened my work up to a new chapter of art history, and I have since identified many sculptors as important reference points for me such as Arturo Martino and Costantino Nivola.

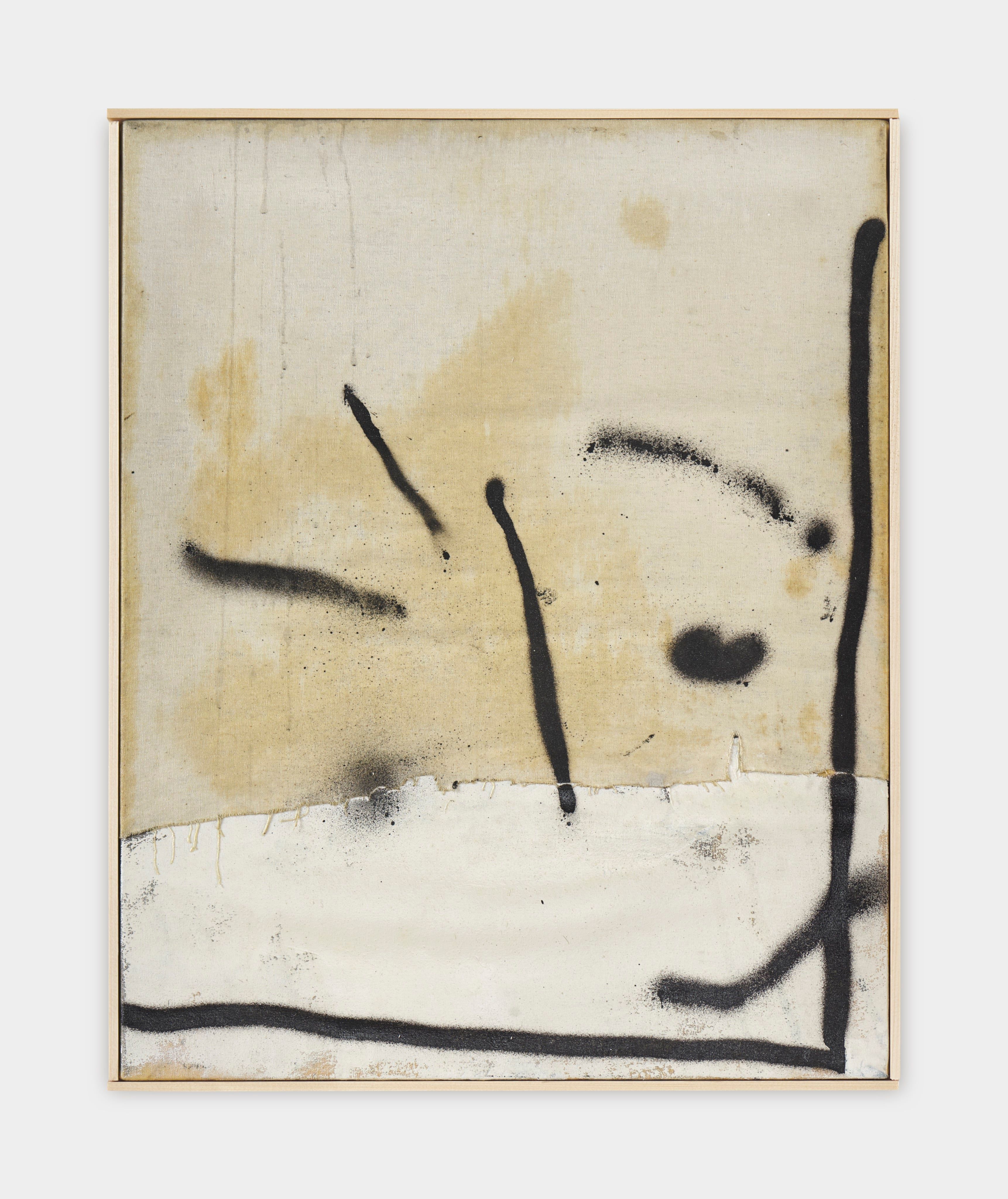

HBB: Can you talk about your last exhibition, “Die bunten Tage” (2022) presented at Galerie Neu in Berlin?

LF: That was my first show with Galerie Neu and it felt like an introduction for me. The body of work did not have a very tight theme, or meditation on a specific subject the way some of my other shows do. The title translates to “the colorful days,” but “bunt” can also mean tinted, stained, or many colored. The word reminded me of “poíkilos,” a Greek word that I came across while reading Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. The word means spotted, variegated, or multi-colored and can be used in Greek lyric poetry to describe the foliage of a plant, the pattern on a bird’s feather, or an emotional state. I like the dual nature of this word, which relates a visual complexity to an emotional one. I feel like painting relies on similar parallels between variegation of form, mark, and color to speak to a variety of sensations, emotions, and atmospheres. In that show, I was trying to push myself into more complicated emotional states, beyond tenderness, and into longing, disorientation, agitation, and joy and the way to do that was for me through color. So, colorful days but not all robin’s egg blue and daffodil yellow.

Credits

- Text: Hugo Bausch Belbachir

Related Content

“Don't be gay”: HUGO BAUSCH BELBACHIR Courts Bravery and Revenge

Strange Bedfellow: An Ode to the Outsider with SOUFIANE ABABRI

“Societies that are beholden to chronological time are immoral.” An interview with MARIA TUMARKIN

DAVID OSTROWSKI Brings Bauhaus to Warsaw’s Galeria Wschód

“More Atmosphere!” BRITTA THIE Paints Life on Set

Coming Into Form – THOMAS HOUSEAGO

CULTIVATED ASPHYXIA: “Exposition N°120 (maybe)” at Balice Hertling

ON MESSAGE: MATT LAMBERT and ERIKA LUST