ATONAL, Decentered: What is a festival?

Over 50 years ago, the building occupied by Kraftwerk, Mitte’s power station-turned-multipurpose cultural complex, supplied heating and electricity to East Berlin’s central districts. Also home to some of the city’s best-known clubs (Tresor and Ohm), today the impressive former industrial facility provides an oasis for sonic and visual art events – including the annual Berlin Atonal festival, founded in 1982 and relaunched in 2013 after a twenty-year hiatus.

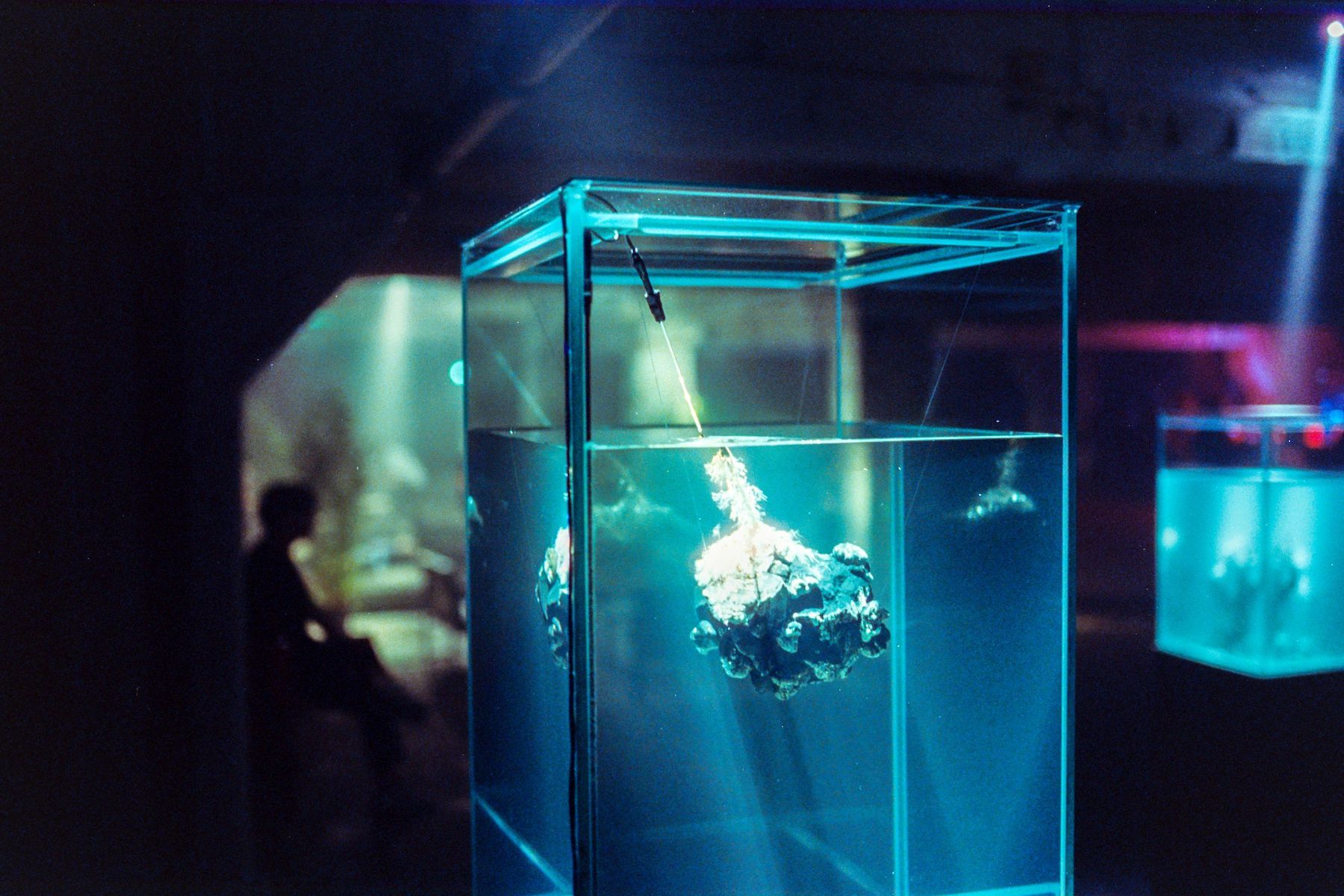

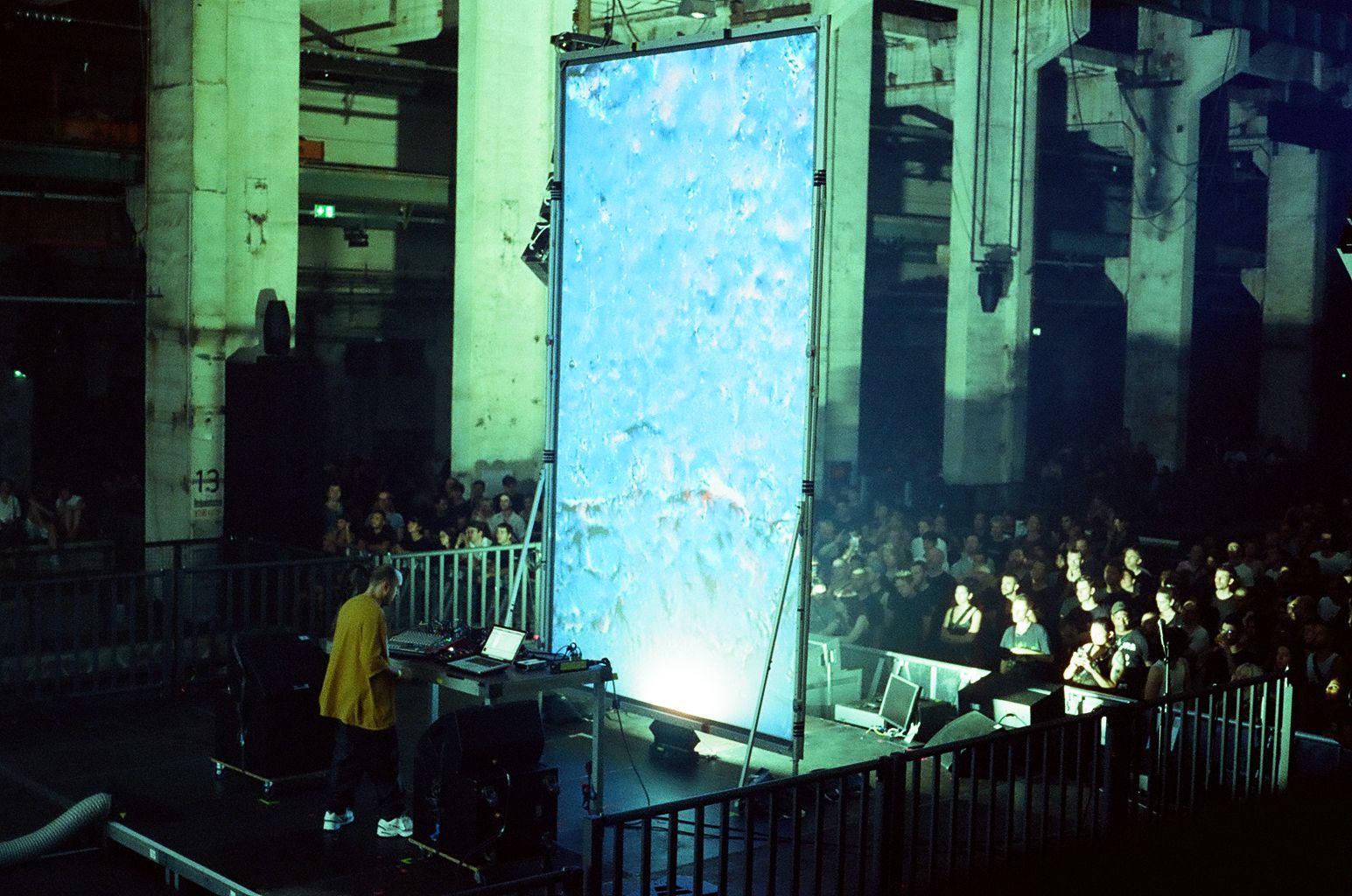

A hybrid of experimental techno and hypnotic artistic displays, the five-day festival took place this year between August 28 and September 1, and featuring a variety of live DJ and audiovisual sets (Amnesia Scanner, Objekt, rRoxymore, and Mala, among others), performance and video pieces (including a massive live projection of Cyprien Gaillard’s Ocean II Ocean, first presented at the Venice Biennale earlier this year), and large-scale sculpture and installation (by artists such as Roger Hiorns, Anne de Vries, and Folkert de Jong). In line with the interdisciplinary approach that has come to define the contemporary cultural landscape, Atonal seeks to enable the collaboration of artists and the intersection of mediums, and to channel the spirit of creative freedom and experimentation that defined the post-1990 art and nightlife underground. After the dust cleared from the event, its organizers – Harry Glass, Laurens von Oswald, and Paulo Reachi – took the pulse of the project.

If you had to describe the mission of Atonal, what would it be? Is there something about the festival that seeks to defy description or categorization?

We don’t think of ourselves or the festival as pursuing a single goal or mission, although there are a few consistent aims that form a kind of basic outlook: to always try and support artists to take risks with their experiments; to avoid laziness, convention, and compromise in our ideas; to always take the audience seriously.

What sets Atonal apart from other festivals of sound? What is it about Berlin that makes the convergence happen here? Would the festival be possible elsewhere?

There are some similarities between Atonal and other festivals around the world, particularly with musicians who participate in the experimental music worlds, artists in the performance scenes, video artists at art festivals and so on. We think what makes Atonal different is how all these elements come together in one space during one week, the emphasis on new works, and the scale and ambition of some of the main productions. Berlin already acts as a locus for many of these different worlds so the festival certainly works with that advantage.

Could you share some highlights or memorable moments for you from this year’s festival?

This year we especially enjoyed working with Cyprien Gaillard on an adaptation of his Venice Biennale work; developing a new show with the Arizonan group Marshstepper, ballet dancer Raymond Pinto and VR artists Sam and Andy Rolfes; showing a new video piece from Stéphanie Lagarde and large-scale totemic sculptures from Folkert de Jong that we have admired for a while; working on new shows from Roly Porter + MFO, Shapednoise + Pedro Maia, Kali Malone + Rainer Kohlberger … but the list goes on!

The visual art program at Atonal was more ambitious and developed than it has been in previous years. What is the importance of having art in a festival such as this?

It’s always been important to us to explore decentering the venue and to create different experiential situations for the audience beyond those that exist directly between them and the stage or the performer. To avoid being “mere” decoration, the various artworks, video works, and installations that fill out the space should have something to say on their own terms. It’s always nice for us to hear from a visitor that they themselves had an experience of decentering at the festival. It means that there was something in their experience of the space, in what they saw and heard, that pulled them in different directions. This is the type of experience we would like our audience to have.

You featured a number of collaborations – between musicians, and between artists working different mediums, some of whom had never worked together before the festival. How is collaboration important to you in terms of creating? How do festivals like Atonal provide space for this?

The most exciting part of doing the festival is seeing new work get created. One of the nicest ways of doing that is by suggesting that two artists who you admire in different ways or for different things work together. In a way it’s like an amateur chemistry experiment, where you expect the result to be somehow connected to the initial elements but can never entirely predict it. This experiment gets even more exciting if it combines elements from unexpected places.