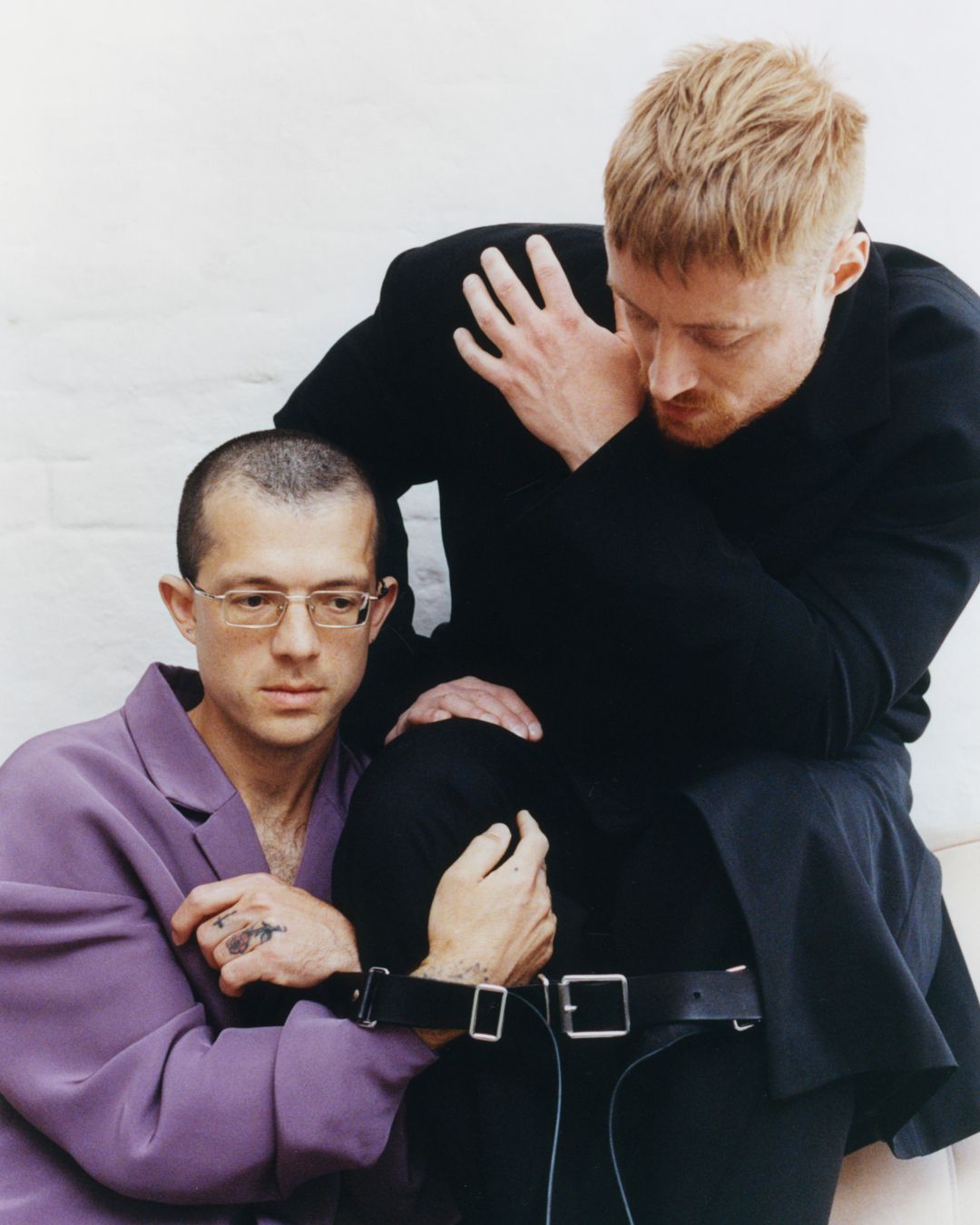

BILLY BULTHEEL and ALEXANDER IEZZI: Sculpting Music in Churches

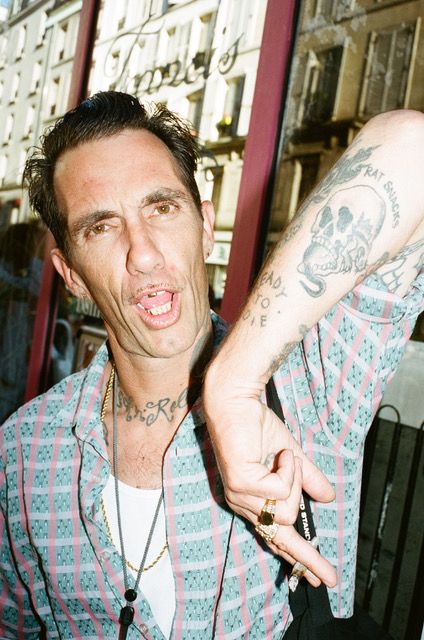

Last October, a band with an enigmatic name released one of the most forward-thinking albums of this young decade. 33–69 by 33 combines machine gun techno with bone-chilling industrial and operatic voices to create experimental pop songs that sound like they’re from another world.

The brainchild of visual artist Alexander Iezzi and performance artist Billy Bultheel, 33 brings together a host of other musicians, such as Ivan Cheng, Steve Katona, NAKED, Patrick Belaga, and Dylan Kerr, to subvert traditional musical practices and reimagine what collaboration means, or could mean, today. Aiming to decentralize power relations, Iezzi and Bultheel approach music like a sculpture, carving out shapes from an archive of fragments. For 032c, the two collaborators and friends discuss power, architecture, and why churches are the perfect venues.

ALEXANDER IEZZI: Hey, Billy. 032c sent us some questions. There was one about collaborations and whether collaborating can be considered a practice in itself or at least inherent to an art practice. What kind of people do you collaborate with, and when do you decide to work with them on a long-term basis? These questions are pretty much based on the way we like to frame the band, as it’s inherently collaborative—a group of people who are making art/music with each other.

BILLY BULTHEEL: 33 came into existence out of a desire to develop new ways of collaborating. We were surrounded by so many creative musicians, videographers, visual artists, web developers, and others, and a big part of the reason why we started the band was to creatively engage with our peers. It was also about working in a way that is fun—writing a song together, making a video, or developing online projects, but always keeping it within these smaller short term projects that didn’t demand too much theorizing.

AI: Even though we are metaphorically at the center of the 33 universe, it’s a space that multiple people can experiment with. There are all these artists we work with who have their own practices, and they maybe wouldn't feel comfortable trying certain things alone. For example, some artists we’ve invited to do videos, don’t produce videos outside of 33—Leda [Bourgogne] is an amazing painter and installation artist, but picked up a camera to extend her techniques into a music video for our song “Sexus.”

BB: And the first album really manifests that musically. We invited a broad array of artists. Steve [Katona], for example, is a counter tenor and normally only works on theater productions. When we invited him to feature on a 33 song, we wanted to make a counter tenor aria into a pop song. I still love that the lyrics—which are about having a wild night out and getting intimate with a lover under a bridge—are in Latin. And I think the idea of being part of a pop band was at first unimaginable for Steve but also a fun change to his professional trajectory.

AI: The people we work with over a longer period really enjoy this sort of space. There is joy in collaborating with people that you like as artists and trust as friends and creating something new with them that involves some kind of risk, or unconventional modus operandi.

BB: Totally, the album was a great opportunity to invite Patrick [Belaga] or Agnes [Gryczkowska, NAKED], and other musicians that have been on our radar for a while, but whom we were never able to find a fitting context for. And then working on a song was such a fun way of exchanging ideas and being creative together. The relationships grow and then the band as a platform grows so organically. Every invitation was pretty instinctive without any overarching-narrative in mind.

AI: Yes, and the band is still modular; different formations can occur in different contexts. 33 is interested in the idea of different power relations, and how you can decentralize power through a group. You and I are the ones who are responding to emails or messages online, but there’s lots of freedom and powerlessness that we give ourselves in terms of what other people can contribute to the project.

BB: Do you have an example?

AI: If you take the song with Patrick, for instance, it’s as much Patrick’s song as it is ours. It’s not like we sat down and wrote exactly what Patrick should be doing. You give power to other people. I don't actually like using the word power, but it creates its own thing—the control of the band shifts and is more fluid.

BB: Something we discussed since the beginning of the band was that we want to avoid chasing pop-star status for you and me, and instead focus on the band as a changing constellation of collaborations. We’re now working on our second album, which is a completely different constellation than the first one.

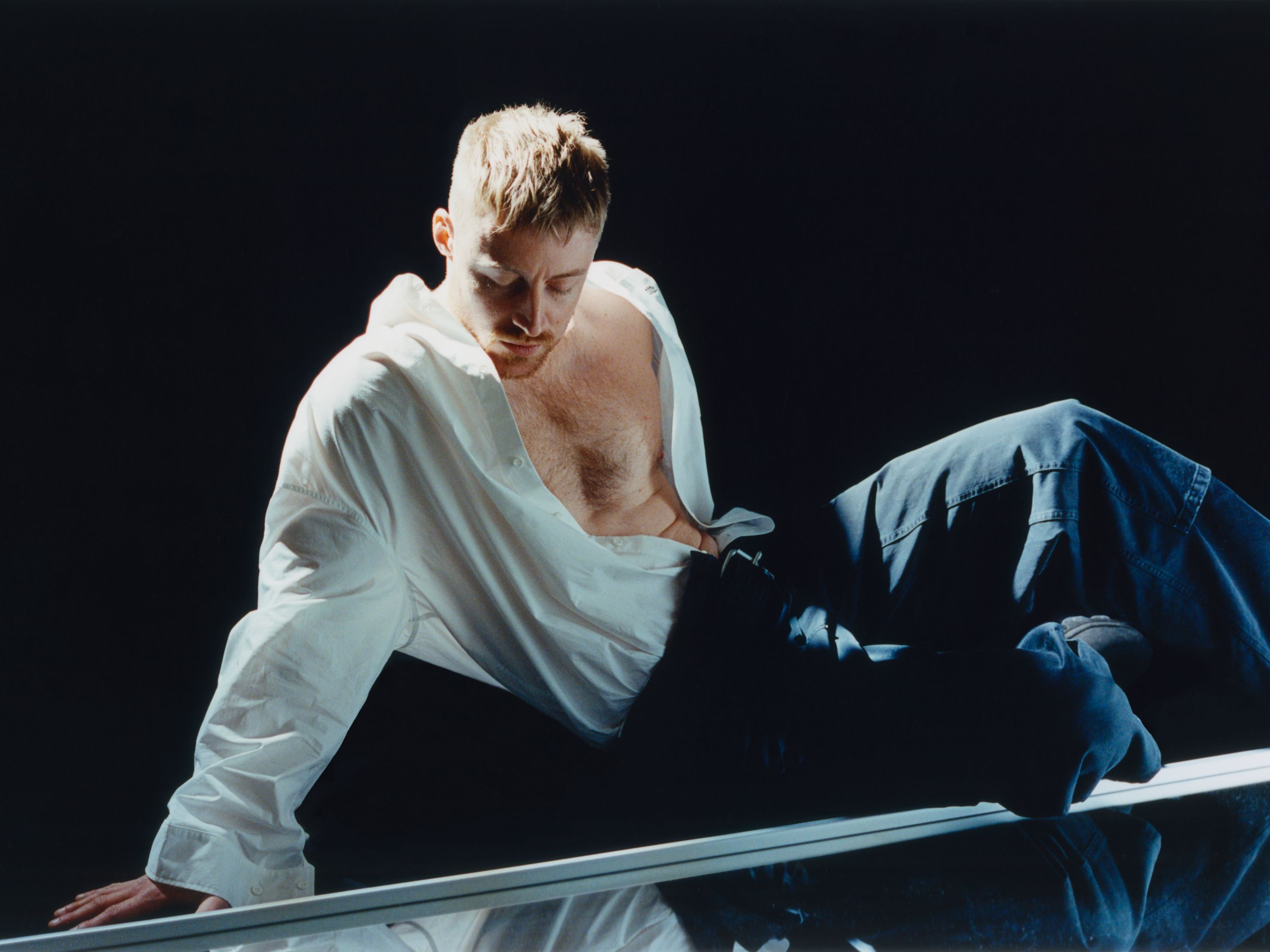

AI: It's kind of an evolving constellation. I think our way of writing music also allows that. The writing process consists of creating a bunch of material. Recording many ideas and then revisiting the recordings much later in an “editing room” to take things apart.

BB: Exactly. It’s a form of a subtractive synthesis—creating a lot of material and then taking things away.

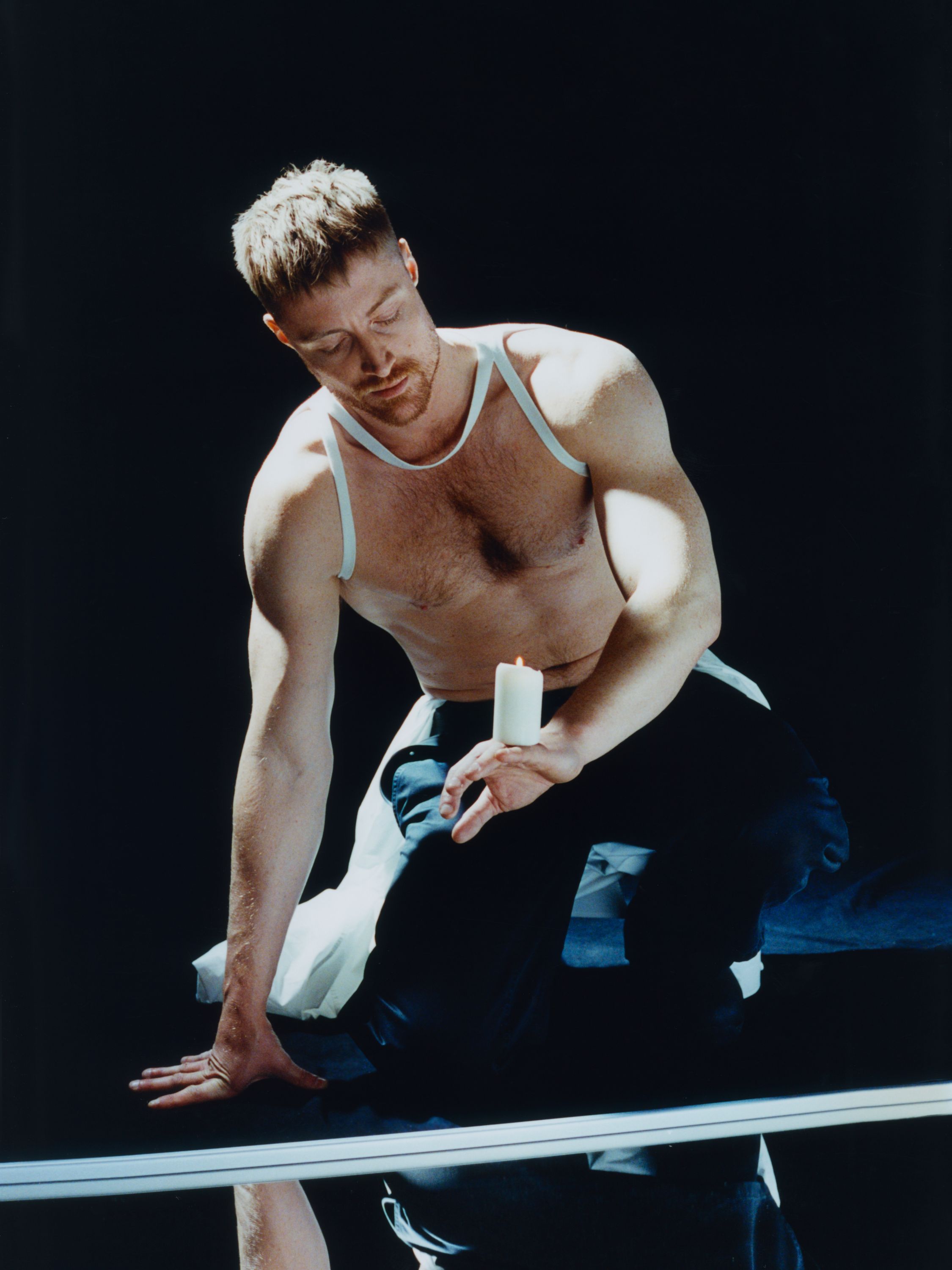

AI: It’s also a sculptural technique. You have a massive stone and then you have to carve into it, create details, and a good shape.

BB: These two modes have been really important for the aesthetic of what we’re doing. There are also many nods to the history of music—metal, punk, or Baroque, for example. And simultaneously, we’re playing with sound in a way that isn’t musical. Mixing up genres to build a collage-like labyrinth, making the modulations abstract and figurative, like a sculpture made of music.

Seth Kim Cohen wrote a book on non-cochlear sonic arts. He talks about sound as an architectural or sculptural phenomenon rather than as being purely ephemeral auditive. We think about music in this sculptural form, as a solid in the material realm. Personally, this is very informed by my experience with performance and always thinking of music for certain spaces and ways of moving through them. I imagine this makes even more sense to you as you’re a visual artist.

AI: In all the writing about 33, people always have to mention that you’re a conservatory-trained musician and that I come from a punk background. I don’t think it’s that simple. In terms of theory and ideas around art making, it’s maybe more about structural notions. It’s not an attempt to create a distinct style but to play with styles—perhaps in the spirit of Dada, trying to be humorous at times, playing with the mood, and surprise. Creating music with a structured approach is equally as important as simultaneously breaking this structure. What Fluxus did, especially around music, is quite inspiring for me.

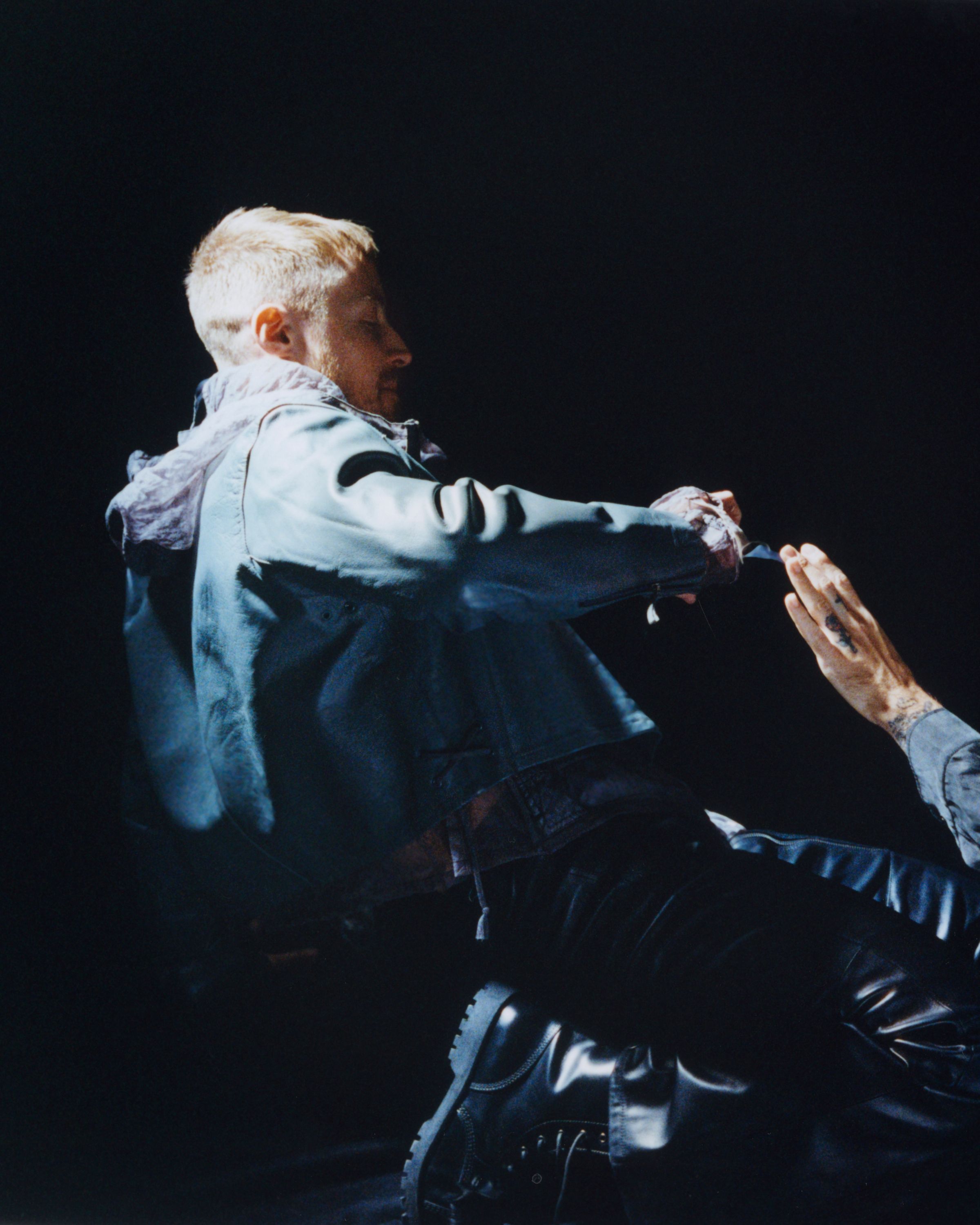

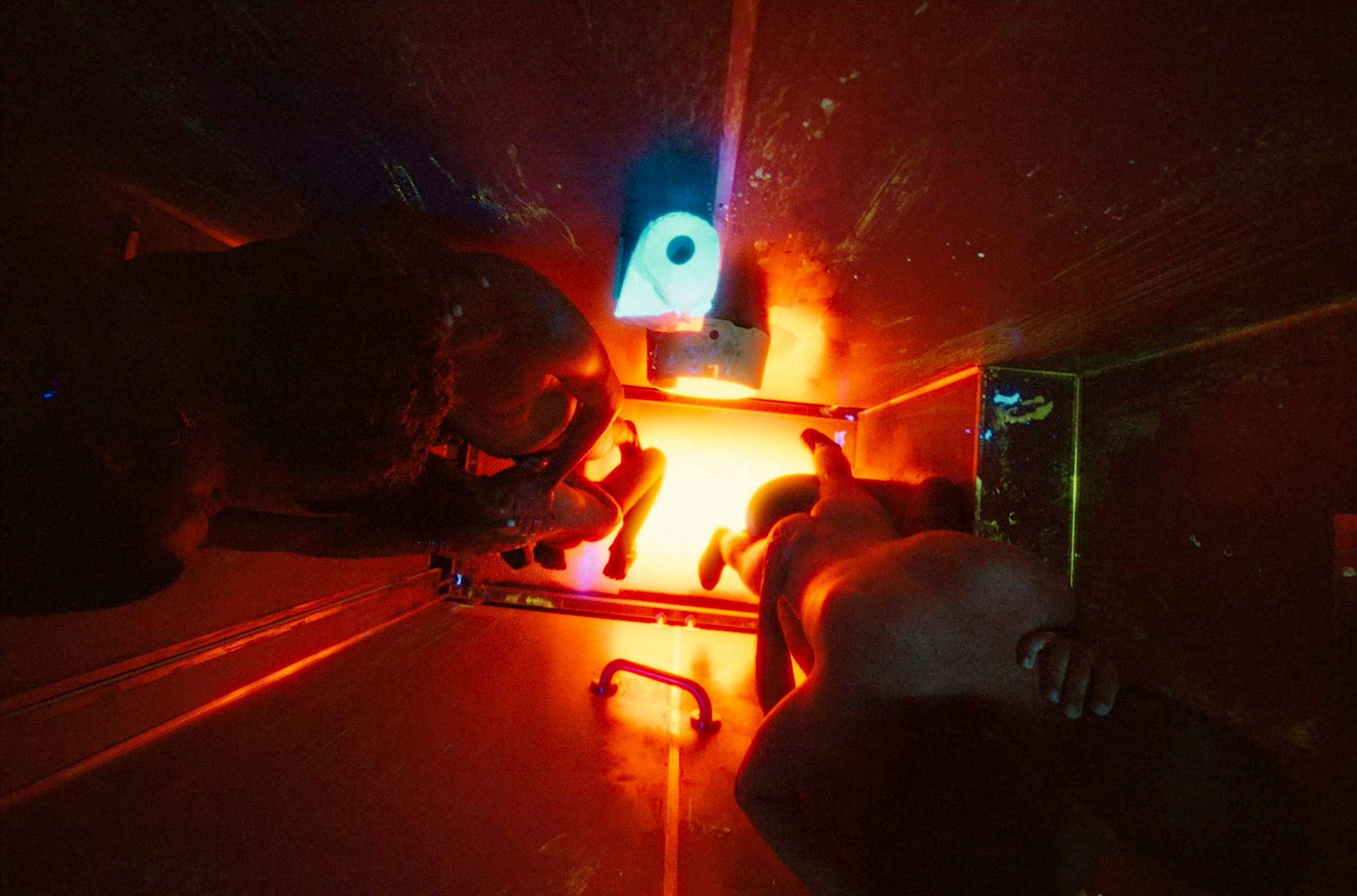

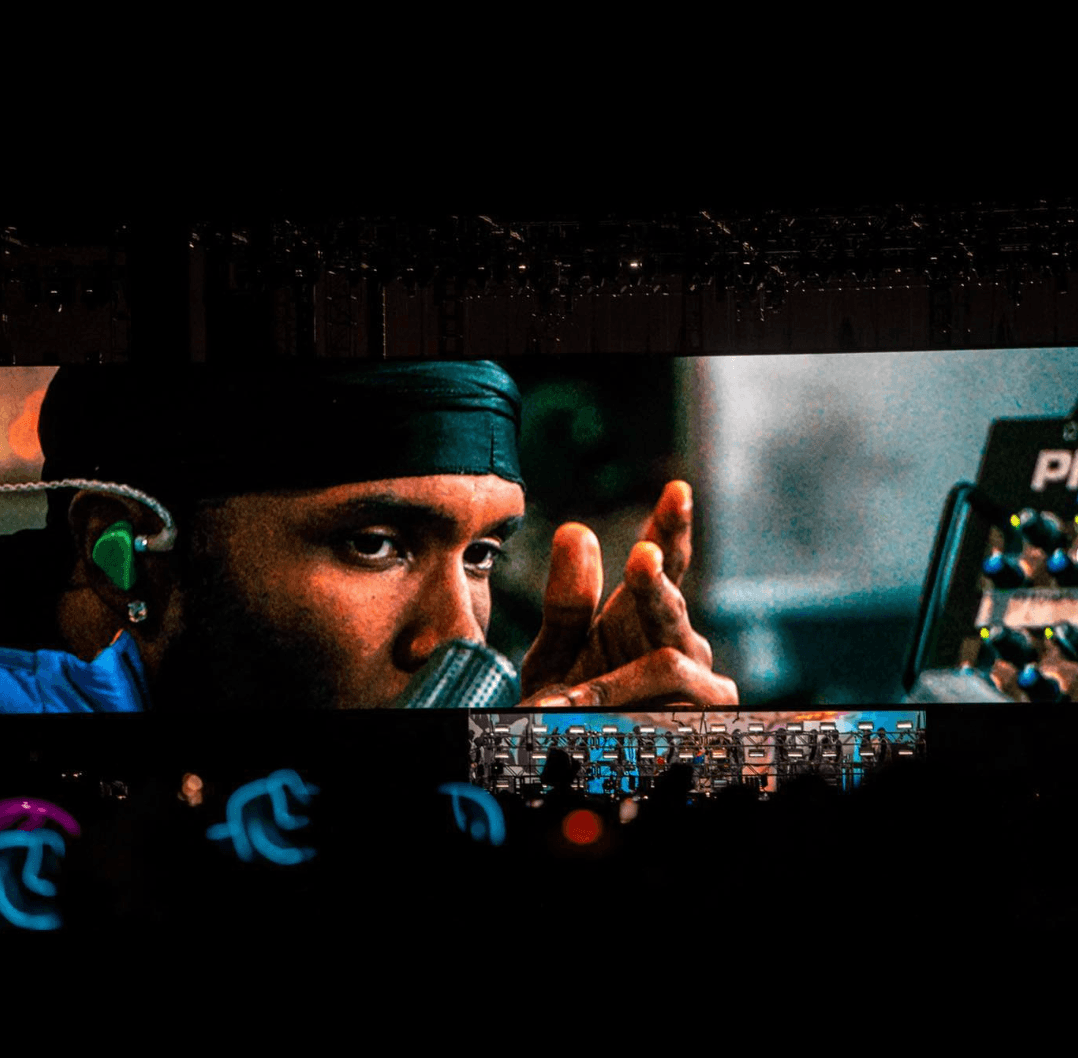

BB: That’s also why the 33 concerts have a very performative and installation nature. Even though we’re playing music on a stage, there are moments where I feel like all of us are actors in a play. We don’t have a single front man who sings every song, our stage personas are almost more narrational.

AI: It’s not a frontal rock band approach to music making. It engages with different senses. It engages the crowd in a different way, it also engages our music in a different way. But we still play almost everything live and I still feel that watching people play music can be really profound.

BB: But there is definitely a potential for a 33-sound-installation in the future.

AI: In terms of power relations, architecture has a lot to do with visuality. You, as a composer, have more of a connection to architecture because so many of your projects specifically deal with an interest in using space as another instrument. For someone who also performs to music, space becomes an invisible member or invisible instrumentalist next to all the other people who are performing.

BB: But then with 33—which really conceived itself through a studio album and not a performance—spatial conceptualization in a metaphorical sense plays an important role. The album moves through different spaces: techno clubs to churches. I mean, we’ve gotten used to performing in actual churches by now. We've even started asking for church or church-like venues when we’re invited to play at festivals or the like.

AI: I feel like it works. There’s so much imagery around churches and their grandiosity. It suits the nature of the band.

BB: Churches are the ultimate concert halls. The technique behind their acoustics have been developed over so many centuries. They’ve always been spaces in which music is celebrated. They are the epitome of architecture and sound merging together.

AI: Many churches have created interesting amplification or equalization systems. There, voices and music reach so many people, and it’s being pushed to become a religious thing. The fact that this space has been developed around these notions lends certain sonic possibilities.

BB: Totally. The idea to go beyond the physical boundaries of your body is very much connected to music and religion—and it’s why they are so close to one another. Performing at Nieuwe Kerk (New church) for the Rewire Festival in The Hague was the perfect example of this. The festival was amazing for lending us this beautiful space. I think the band had a quasi-cathartic experience echoing our songs through its vaults and crevices.

Credits

- Photography: Sophie Klock

- Fashion: Alessia Ansalone

- Photography Assistant: Eden Jetschmann

- Fashion Assistant: Tim Keuschnig

- Hair and Makeup: Naomzz

- Special Thanks: Modern Matters

Related Content

Disco Isn’t Dead. It Has Gone to War

Why WOLFGANG TILLMANS Has Re-Coded Recorded Music into an In Situ Experience

Metagaze: SHYGIRL Stares Back

ON MESSAGE: MATT LAMBERT and ERIKA LUST

HR GIGER & MIRE LEE: Horror, Slime, and Satanic Eroticism

Moved by the Motion: A Portrait of a Roving Band, in Five Acts

Cali Thornhill DeWitt Loves His Uncle Vic

FRANK OCEAN: the Mysterious Artist