Disco Isn’t Dead. It Has Gone to War

|Claire Koron Elat

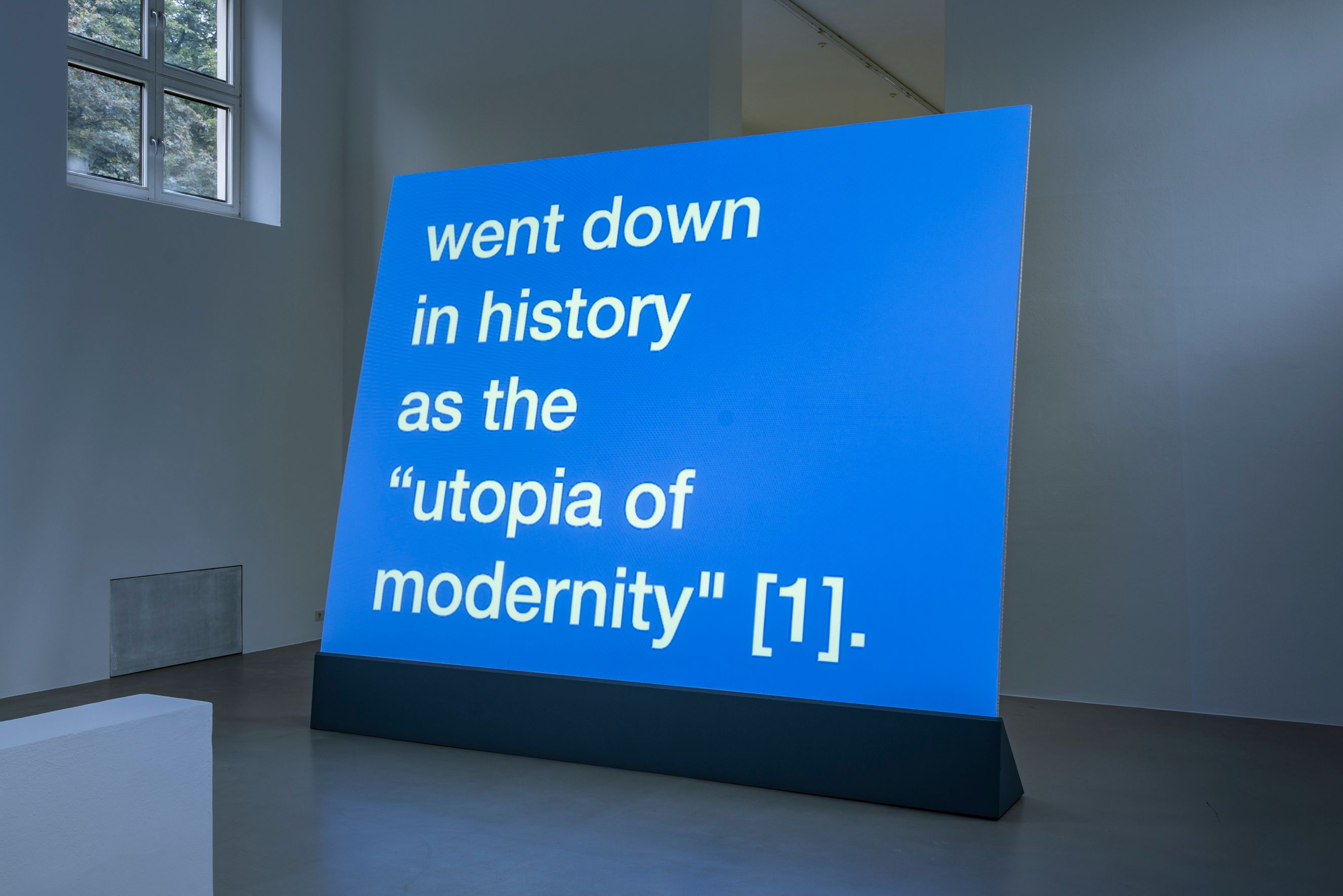

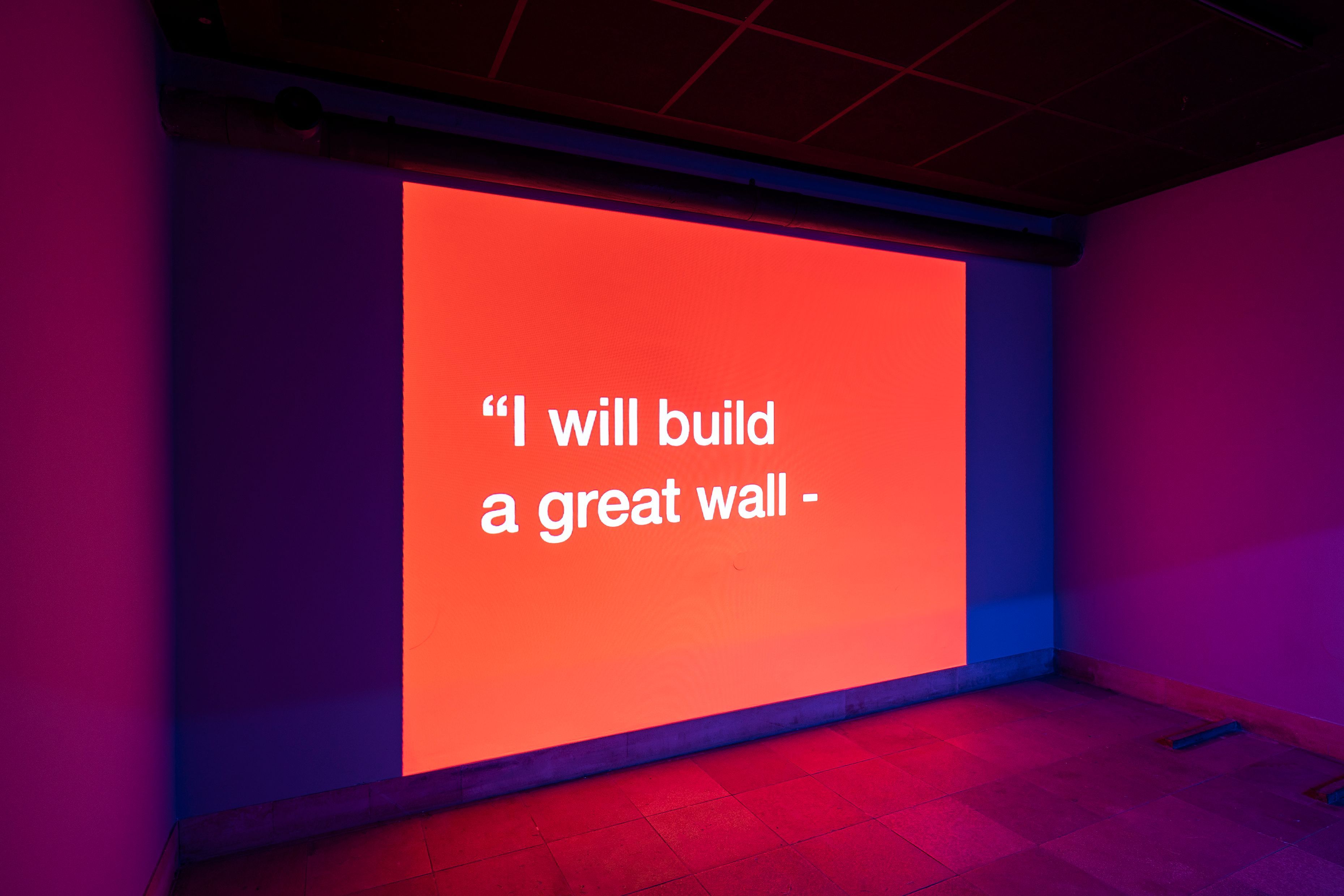

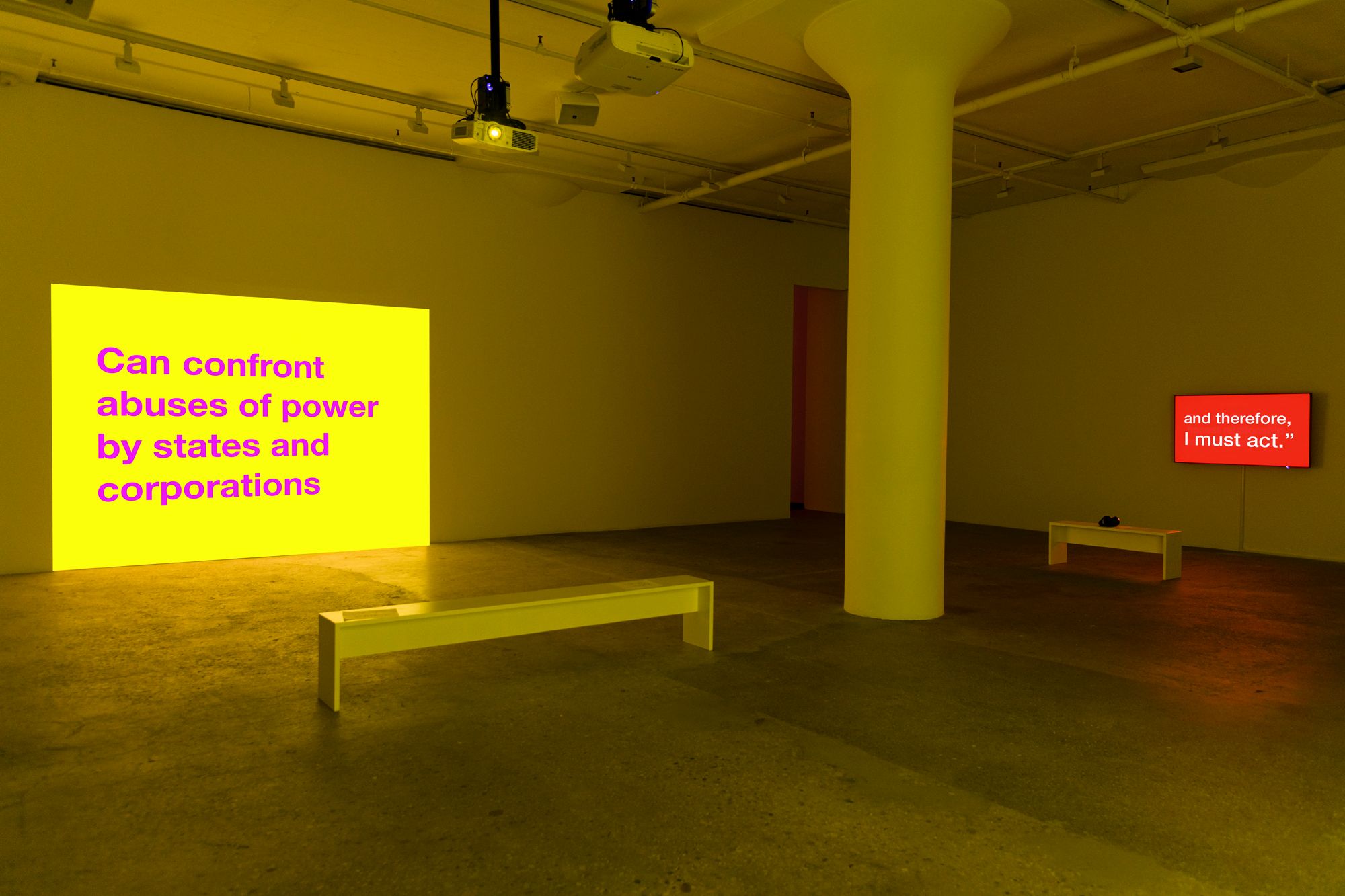

“I was told right now, in the conservatorship, I’m not able to get married or have a baby,’ S. said.” This is one of the quotes sliding over a monochrome video screen by artist Tony Cokes. Taken from a testimony Britney Spears gave after her 13-year-long conservatorship was annulled, Cokes’ work Free Britney? (2022) investigates the political dimensions of pop culture icons to a musical backing.

Since the 1980s, Cokes has been working on complicating music and its relationship to dichotomies like catharsis and torture as well as enjoyment and critical thinking. Quotes included in his work come not only from Spears but also from Donald Trump, Ye, or Mark Fisher. His video essays, as he calls them, visually simulate cultural production in the 21st century and allude to their inherent biases and political nature.

Two of Cokes’ works are currently on view in Frankfurt as part of an augmented exhibition titled “DEMO-,” curated by Ben Livne Weitzman, on the political value of publicly accessible spaces. The site-specific virtual works part of the show, which also includes Morehshin Allahyari, Flaka Haliti, and Tamiko Thiel, among others, can be accessed through the WAVA app across the city. Here, we talked to Cokes about clubbing, the power of sound, and moving backward through time.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: An exhibition you had at Greene Naftali in 2022 was entitled “On Clubbing, Mourning, and Critique.” How do these three realms intersect?

TONY COKES: I was drawn to the fact that they wouldn’t normally be connected. But for me, some of those themes revolve around each other. I made a work about two different 90s moments of clubbing, and I’ve also made a couple of pieces that had to do with mourning and the legacy of particular figures, such as Mark Fisher.

CKE: I think that clubbing has the potential of being a form of critique and of mourning.

TC: Especially with Covid-19, where clubbing took on a very different existence. It was more furtive than it normally would be. I couldn’t help but be hyper-aware of the idea that you occupy certain public spaces in certain ways.

CKE: Public spaces certainly became even more important during the pandemic. They were accessible during a time where much other space utilized for acts of critiquing or mourning was shut down. You’re currently part of a show that takes place in public. The work that you are showing there has also been exhibited in institutional contexts—which would also be public, but less public or semi-public—as well as in galleries. Was the process of making the work different because the context of where the work is shown changed?

TC: Ben [Livne Weitzman] and I exchanged views on what might fit. I was particularly interested in getting something into public spaces, because it’s so often fraught and difficult to show there. Sometimes the planning phase and obtaining permissions and logistical hoops that you have to jump through and questions about when or how they will be permitted are often really complex and time-consuming. For this show, it was a matter of choosing the scale. We took a portion of an existing work and were thinking about relative duration that would work in a public situation. The original piece consisted of two channels of 45 minutes each, and we edited it down to two channels with ten minutes.

CKE: In a previous interview, you said that there are certain things only sound can do, and yet your work is a combination of sound, text, and video—it’s not just sound.

TC: One of the things that sound often does is to allow for an engagement with the body as well as with knowledge, as it’s commonly represented. You can dance and think at the same time, or dance and have a bodily response, and the sonic sensorium can impact, even sharpen, one’s thought. Some people might only think about it as some sort of potential negative or interference, whereas I think about it as a complementary possibility. It can actually change your engagement with the text. At least it does for me, which is why I work with music a lot.

CKE: Is sound even more powerful than images?

TC: They can have a complimentary antagonistic relation. There’s a particular sort of pause or rhythm or contradiction that happens between sound interventions. Sometimes you can charge a text through a juxtaposition that imagines a different pathway or way of relating to reading images or text.

CKE: The design of the short statements on monochrome screens in your works reminds me of “news” accounts on Instagram that post fashion news, gossip, or comments on the current status of culture.

TC: I don’t really follow contemporary design and its uses. My engagements with advertising are more historical and I’m more focused on structural film or minimal visual techniques. Certain relationships in social media and the way things are split up and presented mimic those historical forms in certain ways. I discovered the swipe as an electronic “haptic” surrogate before I had a smartphone. My probably limited view of design is that it’s a way of adding context and legibility to the material that you’re working with. I’d argue that some of those techniques were borrowed from even older, avant-garde traditions. It’s like moving through time, although back then, the content was different and it had a different intent.

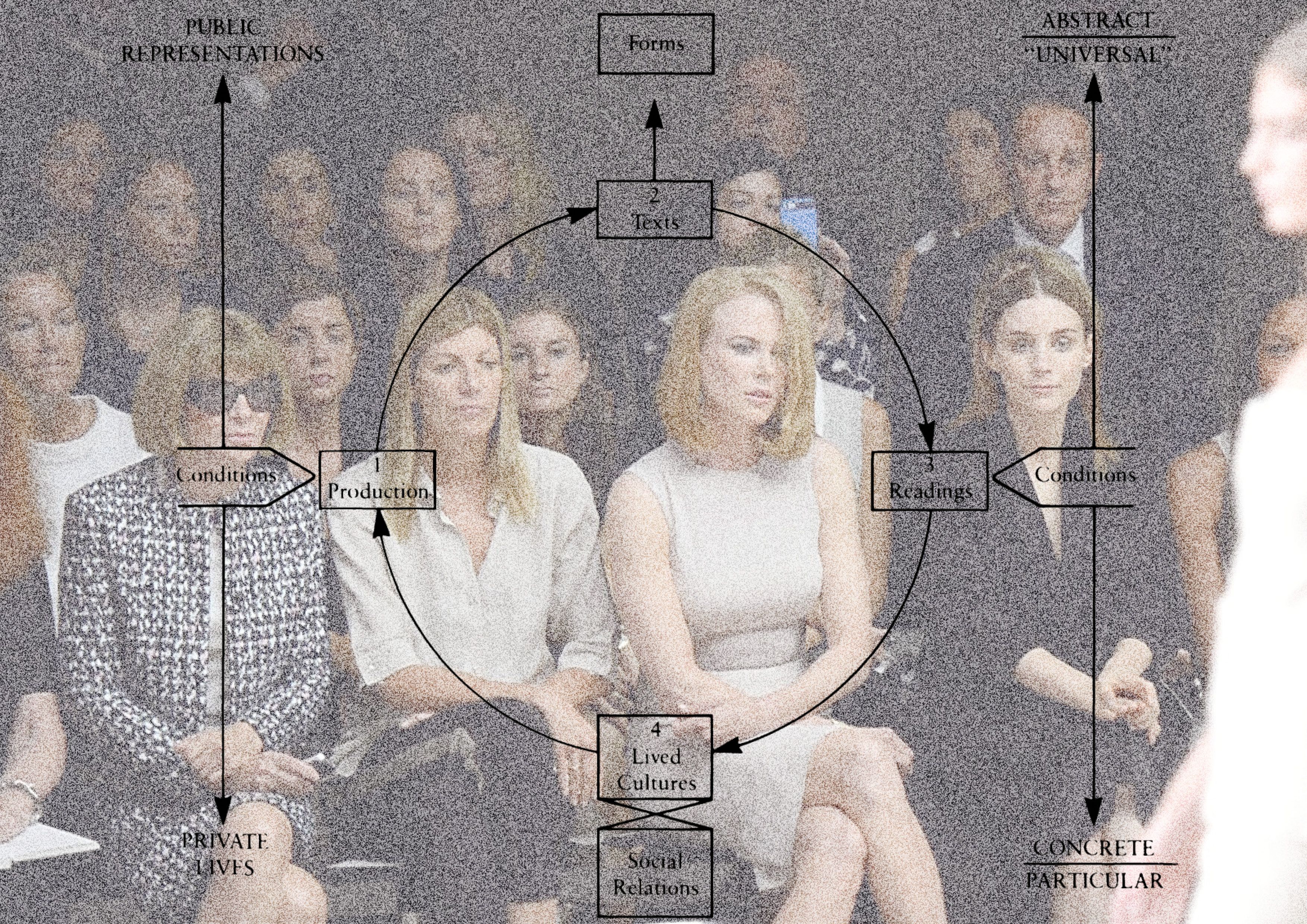

CKE: Historical references in advertisement, mass media, and pop culture are interesting when you think of these three realms as inherently political, and keep in mind that pop culture is often deemed as unpolitical or superficial.

TC: I would probably agree that pop culture is inherently political—even if it isn’t intended to be critical. It’s kind of hard to avoid it. Sometimes, there’s this idea that something is devoid of content and context. To my mind, that’s hardly ever the case. There’s always a context and there are always possibilities for meaning. It depends on how certain things are deployed, not so much just on the intent or the so-called meaning of something. My idea is to use codes that we’ve all seen before in ways that get us to read somewhat differently as opposed to just fold into the flow.

CKE: You made a work about the whole discourse around Britney Spears, called Free Britney.

TC: It was an interesting situation. I wasn’t a follower or a huge fan. I knew some of the music. I remember hearing this radio report, which was based on the article that I used from The New Yorker. Have you ever wondered about relationships with your business and your family that get entangled and put one at the mercy of a punishing, perverse legal and therapeutic regime? It’s hard to imagine that because it’s so visible.

CKE: What’s absurd is that they use Britney’s music to torture inmates in some prisons while she is a kind of prisoner too.

TC: It was a strange anomalous thing. Pop music, when repeated at high volumes can induce stress. Then there are the conditions under which that person is working and making music, which also has problems inscribed inside. I’m attracted to pop material because of the way it goes into the beliefs of culture. What’s acceptable as an activity or what’s pleasurable as a way of being in the world?

CKE: Since music as well as collaging different sounds are such a principal part of your work, I was wondering whether you consider yourself as a DJ.

TC: I often make mixes in order to make video or installation work. I don’t think I’ve ever publicly DJed. I’ve done private parties, lectures with music, things like that. I’d say the first thing that I commit to is the sound. I choose articles that I want to juxtapose as raw material. When I’m trying to edit a piece, I feel like I need to have something to respond to, and something to position the text elements against. I’ll take three tracks, for instance, and just play one after another back-to-back. But other times, for reasons of time or just to have a more varied soundscape to work with, I will actually make an edit for the sound.

CKE: The way you talk about DJing makes it sound like an artistic practice or at least part of an artistic practice—

TC: Rather than a separate category. They’re kind of coextensive. In some ways, I think it is an art form. In an absolute way, if you’re going to guide people through an evening at duration and make often, even political, decisions about what goes into a mix, many factors should be considered. That sounds like artmaking to me!

CKE: If you think of DJs who operate in a more mainstream way, it’s probably not really a form of an intellectual practice. But then there are some great DJs who are also simultaneously artists.

TC: It’s a question of your desires, your context, the scale of things, and how you use them. I probably wouldn’t argue that all DJs are artists—that would be an interesting claim. That’s kind of almost like Joseph Beuys, “Every DJ is an Artist.” I would say they definitely have that potential, and I wouldn’t be exclusive about it. I wouldn’t say, “Oh, you’re a DJ, that’s not possible.” Because I know very well that some of my favorite artists are DJs—or designers, for that matter. But, of course, some people who are artists and have art careers put limitations on what practices to include.

"Tony Cokes’ works SM BNGRZ 02.01 (2021) and SM BNGRZ 01.04 (2021) are on view in front of Paulskirche and Frankfurter Römer, respectively, in Frankfurt. The exhibition can be accessed through the WAVA app until April 30, 2024.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat

Related Content

Runway Music: Musicology for Clothes

Runway Music: Electro-Indie-It-Girls

JANUS: Searching for a Sound that Doesn’t Exist

Ten Cities: Clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Berlin, Naples, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol, and Lisbon (1960 – March 2020)

Iceberg's Visual Soundscapes

“Its Sound and Shape in my Mouth:” EDDIE PEAKE and the Enjoyment of Sexual Ambiguity

“Ridiculously Modest” by Chris Dercon

GRUPPE Wants to Haunt and Heal You