JOHN PORTMAN: God Complex

|Patrick McGraw

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we've always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our issue #34.

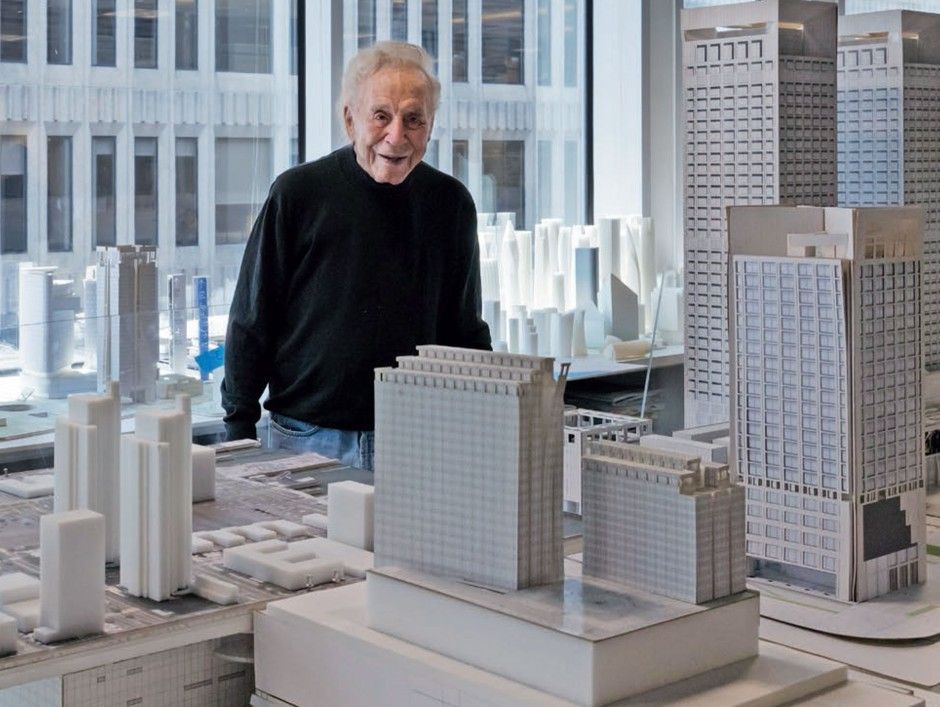

John Portman was perhaps the most “successful” American architect of the twentieth century. Atriums filled with in- ward-facing balconies, windowless malls, and sky bridges suspended between buildings are just some forms of contemporary city life that he invented or perfected. Beginning in the 1960s, Portman built through America’s most intense period of urban decay, and developed a vernacular that can be read as a reaction against white flight, poor state funding, and crumbling infrastructure. Following his death in December 2017, it seems as though Portman’s buildings were designed to fit into a political ideoscape that never came to be, designed for an idealized society. His work is a far cry from urban development today, in which cities have become disjointed, neoliberal jungle gyms.

Portman’s America & Other Speculations stakes out a middle ground between two Portmans, probing deeply the structure and form of his work while realizing the human qualities that inspired them. The book offers a unique reassessment of Portman’s best-known works. Arguably, the American is most famous for his interiors, and more specifically, his atriums: open spaces dotted with pools of water and greenery, surrounded by balconies intricately designed and replicating infinitely upwards. Elevators in constant motion are wrapped with glass, giving the rider an uninterrupted view of their surroundings.

Portman took the hotel, which had been a box within a box, and turned it into a city within a city. It was a new way of considering the user experience. His buildings are sometimes so large they seem to negate the user altogether. In an atrium by Portman, no gesture or conversation is an isolated incident. It is a panopticon for the leisure so- ciety, a way of designing that made its architecture as much a brand as the hotel chain that it houses.

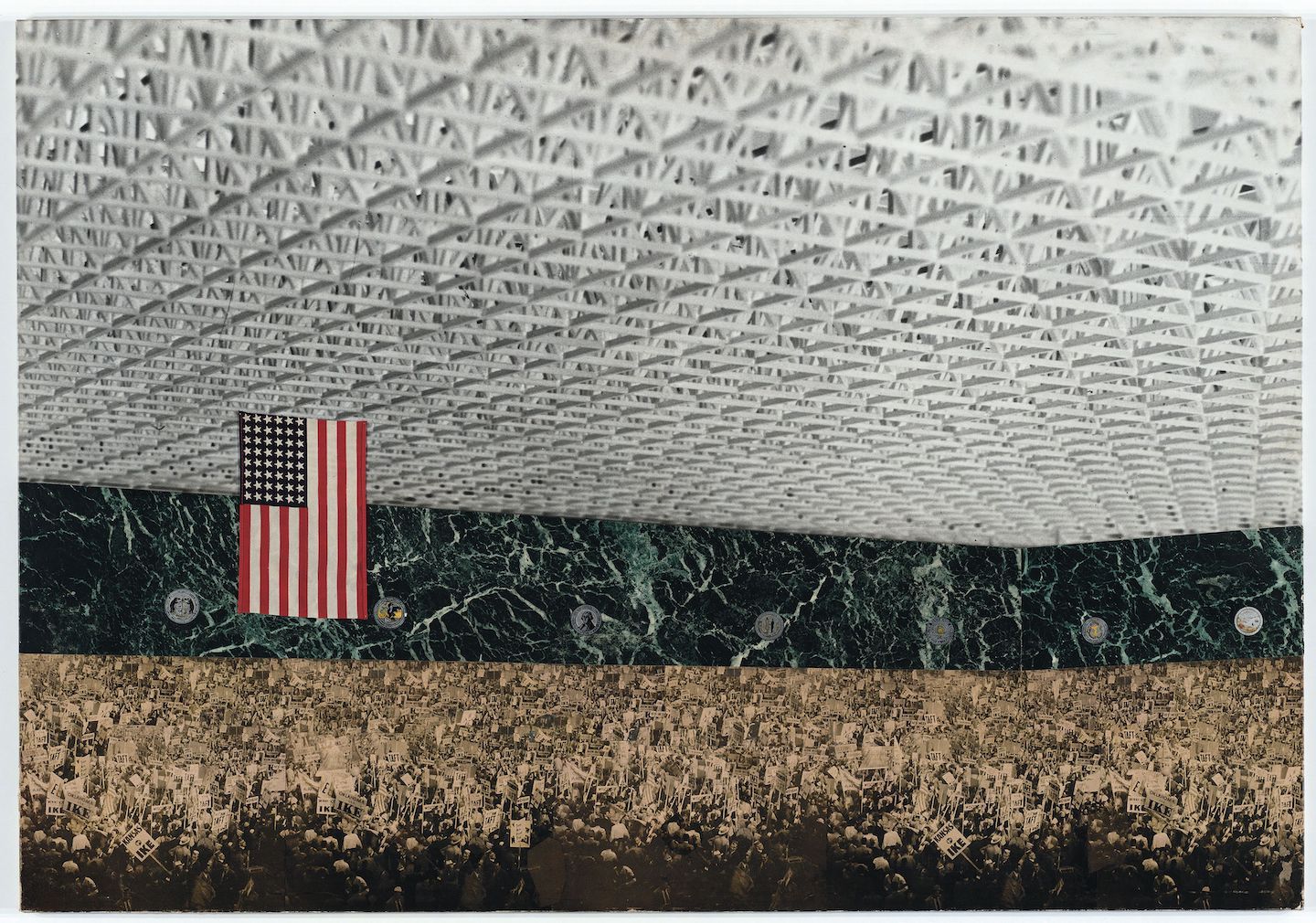

Portman’s style from the mid-1960s onward developed in sync with the deterioration of America’s inner cities. At the time Portman was developing his atriums, crime, poverty, and drug use reached their highest levels in the country. Nixon declared the War on Drugs, and the long road to bankruptcy for cities like Detroit had begun. If Portman’s buildings were utopian on the inside, it was in part because they were designed in reaction to a decomposing urban fabric.

Portman was not only trying to create beautiful architecture, he was trying to build toward an idealized society. Portman’s trademark project, Peachtree Center, built in 1965, is a hotel, office space, and mall. When it first opened, it also contained Atlanta’s first racially-integrated restaurant as well as Atlanta’s first kosher deli. In the 1970s, Portman brought together businesspeople from the black and white communities to form what he called the Action Forum. A group that claimed to be apolitical, as Portman himself did, the Forum’s goal was to tackle socio-economic issues that they felt the state government had failed to alleviate. In a city and state that had still not recovered from some of the worst race riots of the 1960s, this was a radical gesture.

In Portman’s twenty-first century, labor was to become undesirable, if not obsolete. Americans would spend their days traveling from hotels to shopping malls and airports, all without going outside. Their lives would take place with- in buildings that idealized the ritual of shopping and leisure to the point that exterior walls contained no windows, so as not to interfere with shopping cycles and store lighting. When Peachtree Center was first built, it was a single build- ing of 414,000 square feet. Over time, with the most recent addition in 2000, Peachtree Center grew to 18.9 milion square feet across 18 buildings. It’s possible to imagine that it was intended to extend ad infinitum, to eventually form its own city, sealed from the outside world, with the Action Forum acting as a quasi government.

Portman opened his first building in China in 1990, spearheading the now-common practice of an architect exporting their oeuvre overseas. He was perhaps the first to adopt a borderless, politically indifferent view of his own buildings as objects hanging in the web between globalization and free trade, something which has become common practice today, a precursor to Rem Koolhaas’s mini-manifesto “Fuck Context.”

Whatever lineage of architectural ills Portman’s use of unbridled capital may have inspired, there is no overlook- ing the beauty of his work. These are spaces designed with such intensity it is as if they were a direct anima of Portman’s vision. Perhaps a deeper reading of his legacy can explain why he designed the way he did. Not with a megalomaniac tendency to recreate the city in his own image, but as a reaction, to better the city in light of the tragedy it had become.

Portman’s America & Other Speculations is co-published by Lars Müller Publishers and Harvard University Graduate School of Design (Zurich/Cambridge, 2017)

Credits

- Text: Patrick McGraw

Related Content

Architecture Invented Italo-Disco

Cornered: Berlin Review

Modernism is Still Here (it’s Just Vacationing in the Italian Alps)

MIES VAN DER ROHE’s Collages and Minimalism’s Penchant for Chaos

PHYLUM-H: “Medicine, Metaphor, and Architecture”

IWAN BAAN: Moments in Architecture

Half a Century of Civilian Sketches from the UK’s UFO Desk

HATE SUBURBIA: The Conspiracy of the Garage