HATE SUBURBIA: The Conspiracy of the Garage

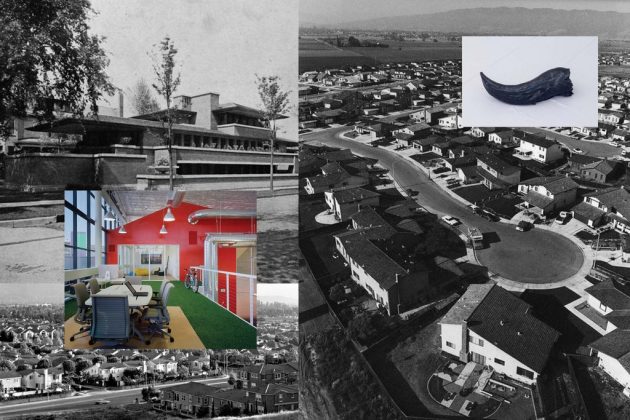

In their new book, Hate Suburbia, artist Olivia Erlanger and architect Luis Ortega Govela investigate the history of the garage and its influence on US American life: in the development of suburbia, Apple’s first computer, and Gwen Stefani’s breakthrough hit for example. The book presents a striking causality between the garage’s various usages over time, a loop in which conservatism and counterculture continuously feed back into one another. The garage appears in Hate Suburbia as Frank Lloyd Wright’s tool to reenforce heteronormative, patriarchal family structures; vital to the commodification of the home; the tech nerd’s man-cave; and, of course, a particularly blank canvas of a space to be inhabited by creative and innovative enterprises.

Besides Ortega Govela’s edible of an essay on the conspiracy of the garage, Hate Suburbia features a conversation between Steve Wozniak and Gwen Stefani as well as a discussion between four gallerists who run or ran their businesses out of – you guessed it. Beginning with Octave Perrault’s foreword and further illustrated through collages by Erlanger and Ortega Govela, the suspicious ubiquity and influence of the garage catches up with the reader. Once you recognize the stable – birthplace of Jesus – as its predecessor… Honestly, you can not unsee this.

A book about suburbia is naturally a book about an idea of home as well. Can you describe yours? How does it relate to your cultural image of suburbia?

OLIVIA ERLANGER: It took four years to move into my apartment in Chinatown due to a mix of traveling for projects and a reticence to commit. After year three, I realized I should unpack and settle in. The space remains predominantly functional. There isn’t much besides books, a light pink couch, tatami mat and artworks from friends. The sense of belonging I have in my apartment contrasts the way I felt growing up in suburbia. Memories of it always bring up a sense of alienation and isolation. Growing up in the suburbs, having previously lived in the city, meant I was constantly aware of what the burbs were not. There was no culture, there were no people, there was nothing but the inside of a car and potentially driving somewhere to get high away from parents, teachers, and ultimately ourselves.

LUIS ORTEGA GOVELA: I’ve been leading such a nomadic life for a while now that it’s extremely difficult to think about home as a static place or a set idea. In a sense that’s also why the title of the book is Hate Suburbia, to antagonize yet acknowledge the very rigid heteronormative concept of what home is or should be. I like to think of home more akin to the concept of a drag house, not a geographical space but found within the people and friends that you make your family. I use my computer and phone to create a sense of continuity between the different spaces I lived in. Part of my interest in the garage was that the technologies which I was using to replicate home were invented inside that space. It seems natural that the technologies which allegedly emerged from the garage are a continuity of the car becoming a satellite or mobile part of home. I grew up in the north of Mexico with a glamorous vision of suburbia. It was an image that I absorbed through films and TV shows and was ultimately, aspirational. At some point in the 80s, economical instability created a trend to buy property in America. My family bought a bungalow in a Texas suburb, situated around a golf course. I remember the first time I went there I couldn’t stop crying. I realized I was in the image I had consumed for so long from a distance. Being inside of it was actually quite depressing and normy rather than exotic. I was both scared by and attracted to this hardcore realism.

Luis, what do you actually think of Frank Lloyd Wright?

LUIS: When I was writing the main essay, I was obsessed with Wright. It was almost like being in love. The underlying conspiracy of the garage I propose is one which traces the invention of the iPhone back to Wright, which he would’ve loved and in fact probably would’ve written himself. Throughout the two years I spent researching him, I saw him as a genius and put him on that pedestal he always demanded to be put on, but my period of infatuation is over and I can’t help but categorize him as a Trumpian character who constantly claimed his own influence over modernism. Ultimately, as with any narcissist, I’ve come to accept that he is just a giant asshole. His genius was that he tapped into the changes and anxieties of his era and preemptively designed for them. This may have helped push his progressive ideas about space, but ultimately he was a white patriarch who replicated his own vision of the world. Early on in his career, he developed a revolutionary concept of home. It nevertheless reinforced concepts of gender, ownership and white supremacy. He was a misogynist who would always refer to his clients as the man of the household even though it was often the wives who urged their husbands to commission him. This is reflected in the way he designed kitchens and the actual spaces designated for the housewife as secondary to the male centered spaces in the home.

OLIVIA: Wright is one of the most beloved architects from the U.S and has come to symbolize a kind of productivity and pragmatism that is uniquely American. He essentially provided the stepping stone between a Fordist line of production and that of designing homes for specific familial roles.

Real talk: where did the interview between Gwen Stefani and Steve Wozniak come from?

OLIVIA: I love this! I’m sad to say, I wrote the interview, so any excitement over our overlapping interests with Steve Wozniak and Gwen Stefani was constructed. This is my “Million Little Pieces” moment, a small victory in a long history of media fabrication and distortion. It illustrates one of the main arguments in Hate Suburbia – the idea of “reality distortion.” Space is a determining factor in the construction of reality and thus, identity. The “programming” of a room influences the activities and interactions that can occur within. A deprogrammed space such as the garage allows for reality distortion because there is no prescribed action or way of inhabiting the room.

LUIS: I instantly thought of Tom Kummer’s Pamela Anderson and Christina Ricci interviews. Both Olivia and I have collaborated with friends in the past and were interested in exploring these partnerships expressed through the characters of Stefani and Wozniak. For both, the garage was the space in which their love / private life became an enterprise. In the case of Woz his childhood friendship with Steve Jobs became Apple and in Gwen’s case her relationship with her then boyfriend Tony Kanal became No Doubt. This imagined yet real conversation also intersects two eras of the garage, that of the white heterosexual male of the 60s, and that of the 90s counter cultural heroine.

OLIVIA: In many ways I was trying to represent a patriarchal figure who was trying to maintain control over his hegemony. In my dialogue, Steve Wozniak, a techno utopian in his youth, is now an aged pessimist who believes that the capitalist machine will always subsume what is perceived as an “authentic” selfhood in order to produce increasingly more differentiated chains of commodity. He argues with Stefani over the construction of identity: can it exist outside of branding and aesthetic? Gwen reminds him, that of course there is still truth in individuality, but that an individual is most powerful when supported by a community. Their conversation reflects my own doubts in the viability of an “authentic” identity as we venture into a garage-less future. It feels like we have fewer venues for alternative thinking. The communities that rallied around Woz and Gwen paved the way for their work. Without those communities, we are left with transparent platforms that function as Woz describes, branding machines that reflect our constructed lives as images of individuality for profit.

Speaking of commodification: commodification and abstraction of the home is furthered through platforms like Airbnb. How does Hate Suburbia relate to your practice as part of the artist group åyr?

LUIS: I see åyr as four architects experimenting as artists, and the art we make is space. The collective started when we decided to hack into Airbnb by renting out apartments and opening them up to the public as exhibitions. A year after doing this, we received a cease and desist letter. Amongst the many violations we had committed against their terms of use, the main one was the misuse of space. It is prohibited to rent out an apartment on their website for purposes other than lodging. For a company that is built upon giving virtual access to the intimate spaces of homes all over the world to have a problem with how space is occupied, without complaints from the owner, seemed crazy. With Hate Suburbia, I wanted to analyze the relationship between virtual and real space. I wanted to write something that dealt with this condition of homes being available everywhere but also the way it is being controlled and a recent history of the subversion of these norms. So I ended up with the unsexiest of subjects: the garage, as the space which reintroduced production in the purely residential zone of the suburbs and also as the ultimate space to be punk. Looking at the garage has informed the way that I think and occupy space, it has also given me the longing to create more rooms that can queer architecture, that can contest normativity and habit.

Olivia, at what point did you enter this project?

OLIVIA: We had both been cultivating an interest in the garage within our own practices. Before we began working on the book, I was working on a project for Balice Hertling NY, which loosely explored ideas around a declining American middle class. This is one dimension of a constellation of research I’ve been engaging in on the construction of value and how commodity moves through and changes space. In this show I included a piece called Palimpset, which was a garage door riddled with small oozing holes. I was interested in the garage door, as a threshold that led to an ouroboric narrative of aspiration, homeownership, mortgages, bank collapse, and ultimately the foreclosure crisis. The garage is an icon of suburbia, but it is also the space where most Silicon Valley start up’s origin stories are set. In this sense I saw it as creating a feedback loop. In many ways these companies created the environment for the digitization of currency to occur, which in turn led to over lending by banks in loans and lines of credit, ultimately destroying the home and the garage with it. Through our mutual friend Octave Perrault, I learned soon thereafter that Luis had written the critical framework for my sculpture. We agreed on the spot we would write the book on garages. And now we have.

Can you talk me through the imagery of the book?

LUIS: Our collaboration started with our interest in the typical American garage that I grew up with through pop culture. So we began communicating our ideas about this space through films and visual references that ignited certain perceptions we had of the space. In turn we had amassed a large collection of images alongside my architectural research on the garage.

OLIVIA: The collages are comprised of a collection of images including the new Googleplex designs, Kevin Spacey, our own sculptures, documentation a of Jannis Kounellis work which was his first show at L’Attico, a converted garage gallery in Rome, a house on fire etc. Most of Hate Suburbia looks at the garage analytically, so it was nice to consider these as polyphonic representations. The sculptures we worked on collaboratively during my residency last fall at Rupert in Lithuania. We spent four days scavenging junkyards for materials and combined auto parts with simple machines, like my favorite espresso maker, from the residency. Rupert is both the site of a residency and a tech incubator, with office co-working spaces in the basement. The residency itself was like living the kind of flexible, deprogrammed space that garage provides and collage was a great medium to express how multifarious the garage is.

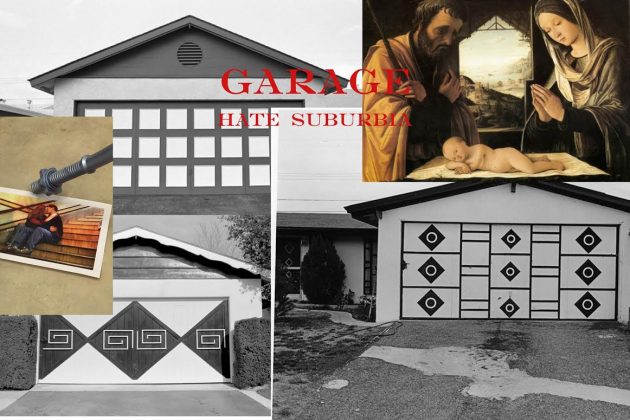

LUIS: I actually don’t like thinking about these as collages but as mood boards. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of a mood board, especially how they are used in commercial design. Conceptually it felt the strongest as Suburbia seems to exist culturally as a series of reference images. The cover was the first of these mood boards I made in a moment where I had reached a point of stoner paranoia in which the symbol of the garage kept appearing everywhere as the typology which created suburbia, the mythological birthplace of tech-entrepreneurship, Apple and Disney, in short it seemed to be part of the foundational stories of all great inventions of the 20th century. I started thinking about the stable as the predecessor of the garage and then I had this Dan Brown moment and it hit me that Jesus was allegedly born in a stable. Suddenly, in my mind Christianity was founded on the same myths as Apple and Hewlett-Packard. I had lost my mind. I emailed Pier Vittorio Aureli, my thesis advisor, that Lorenzo Costa nativity painting with the subject line: Jesus Garage!! He never replied and hasn’t since.

OLIVIA: Well, I’m a believer, Luis! The cover is kind of a code further illustrating what we have come to define as “The Conspiracy of the Garage.” Luis made this with an Illuminati vibe, as if the nativity scene mirroring the formal composition of American garages is part of a larger, cosmic, design. The hacked Prada font points to a kind of consumerism that I think we both love to abhor and secretly idealize.

LUIS: Writing Suburbia in the Prada font was beyond the perfect mood. It was also a nod to our siblings who are stylists.

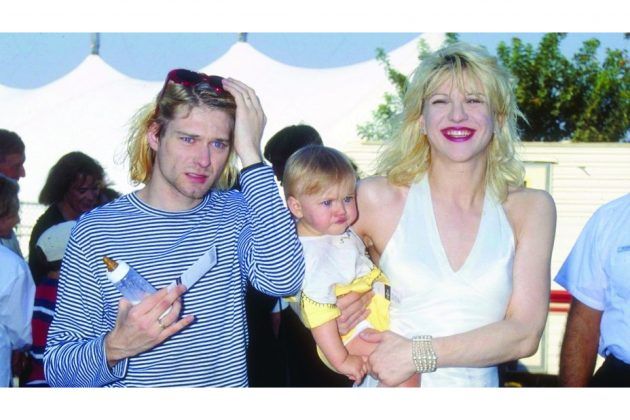

In the book, there’s this picture of Courtney Love and Kurt Cobain. To what extent is Hate Suburbia also about personality cult, narcissism and the idea of the artist?

OLIVIA: The majority of the book looks to Steve Jobs and Frank Lloyd Wright as the main innovators of the garage as a typology of invention but it also reveals their self-mythologizing and narcissistic tendencies. For example, Wright and Jobs would alter the dates of their creations so they could be “the first” and both went on to obfuscate their personal histories, changing facts about their families and upbringing as it fit with what was most advantageous.

LUIS: I’m pretty sure that both Jobs and Wright’s conception of reality is what made their work so influential. They refused the collective vision of the world and instead focused on their own ego driven version of reality. Both Frank and Steve operated within delusion, manipulating their existence into a new identity. Jobs specifically was known to be powerful enough to make you forget reality, creating a sort of contagious madness and anyone who got close participated in the delirium – to the point that he convinced himself and people around him that his daughter wasn’t his for a long period of her life.

OLIVIA: I am less interested in the narcissism inherent to these individuals, but in the power of their Charisma, Uniqueness, Nerve and Talent. They altered their histories and innovated technologies of space and communication which would allow others to do the same, on a massive scale. The kind of cult of personality that we exist in now is unprecedented as cultivated images, aesthetics and narratives collide across social media and physical reality.

What does that image of Kurt and Courtney represent to you?

LUIS: That image was the first public appearance of the Cobain’s as a family. At this point, they had become the ultimate heroes of the American Dream. It’s the only picture of that day where you can see Kurt looking hella stressed. It shows the Cobains as suburban outcasts who had used the garage to rebel against the normative history which created them, but now reproducing the same idea of family that they had defined themselves against. It reveals the Faustian bargain the artist always has to take.

OLIVIA: The idea of the artist is also intrinsic to the garage. In many ways the garage provided a place for outsiders and refuge from mass culture. Cobain is a Coleridgean figure. His tragedy is visible even in this photo … his Kubla Kahn disintegrated on the covers of trashy magazines. He came to define teen angst and the kind of suburban alienation I was speaking to earlier. But also became an icon of rampant consumerism (cc: Justin Bieber wearing Kurt Cobain t-shirt). What Kurt and Courtney came to represent and why it is so central to our story, is a couple that while born out of this kind of “otherness” that were so rapidly commodified that they could no longer find shelter anywhere. This also brings up the next iteration of this project, Macho Villi, an installation we are doing 83 Pitt St. opening the weekend of January 28th, which will be the NY book launch for Hate Suburbia. Macho Villi is a commercial presentation of our book, a kind of window display that examines the idea of a balloon frame as a colonizing agent and looks at the artist as a Machiavellian shapeshifter.