Close to the Hedge: KASIA KUCHARSKA

|Victoria Camblin

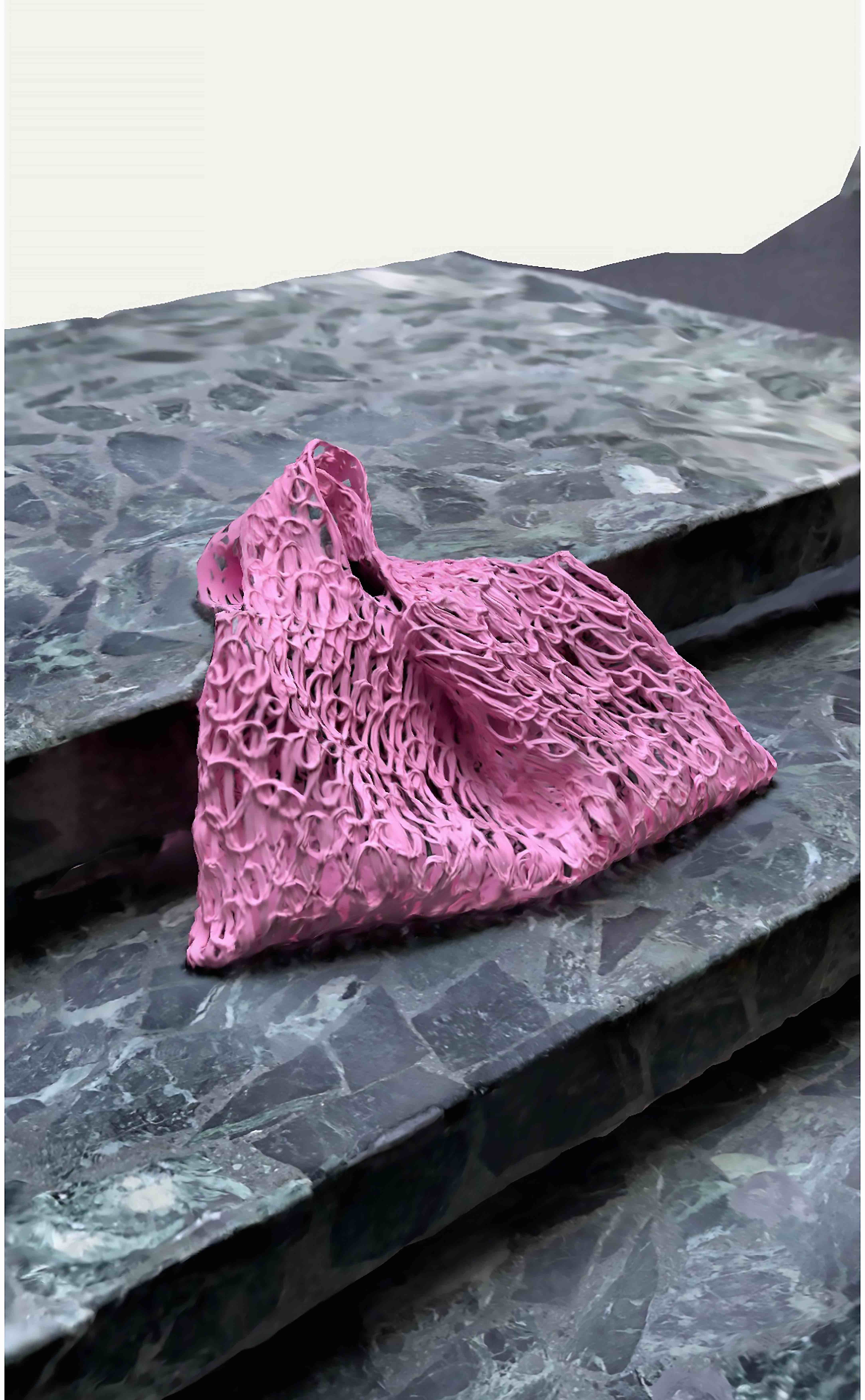

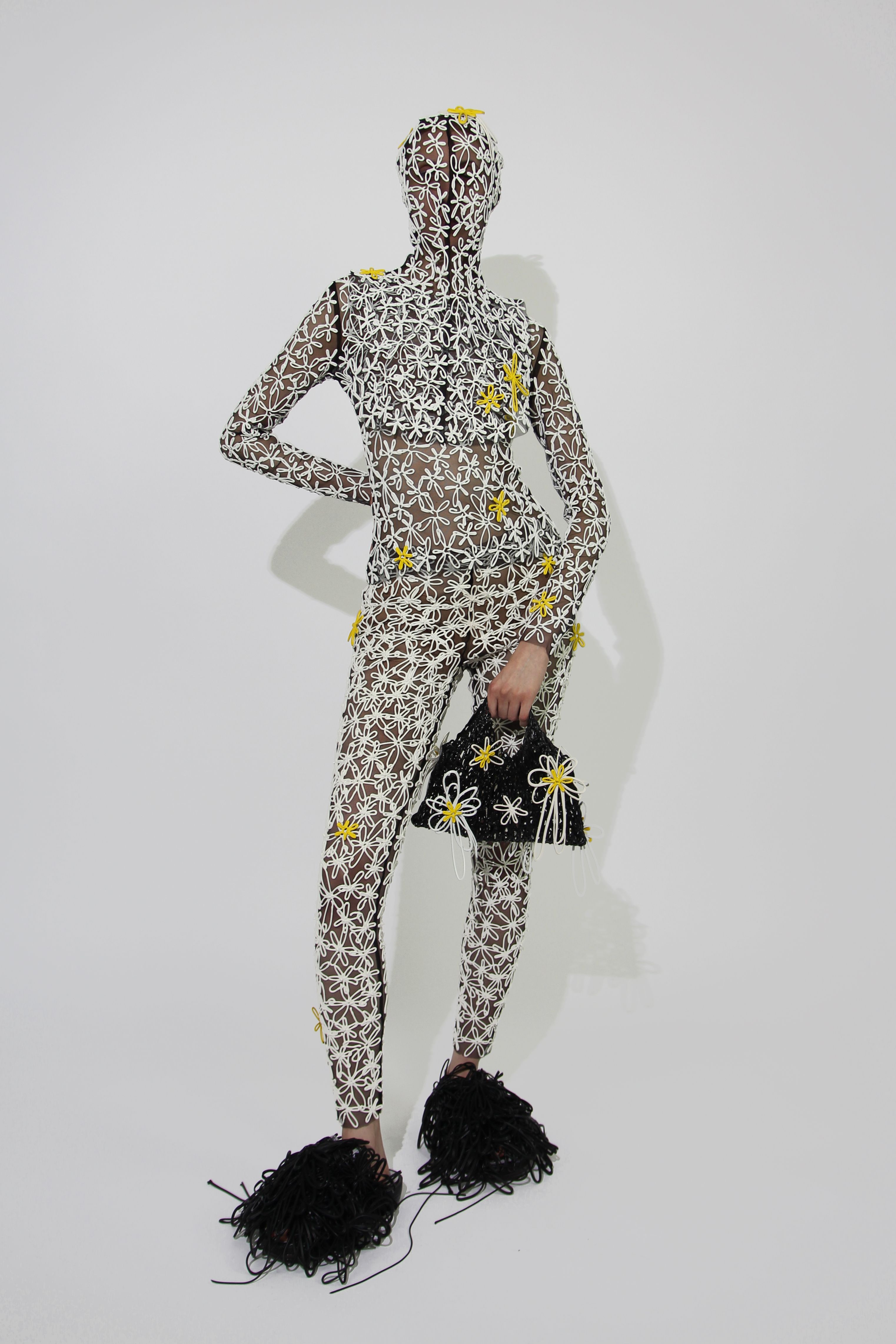

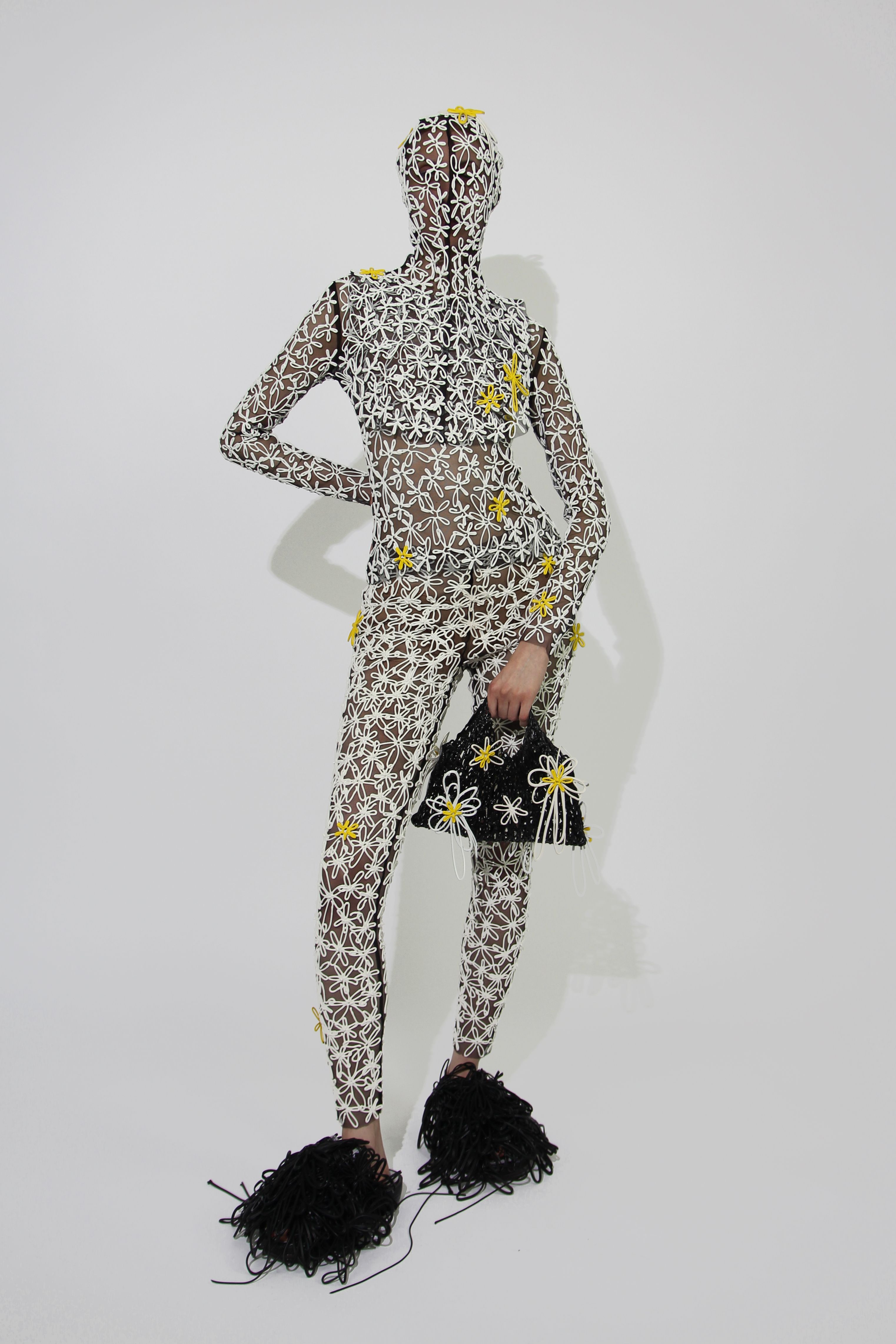

The fashion calendar is not synchronized with the planetary one. During fashion week, against the backdrop of the changing leaves of Paris’ chestnut trees, brands present clothing intended for the season you just exited — a compelling discordance between garment and globe that, if anything, engenders desire. As you unbox your winter coats, you can already begin to dream up looks for next year’s thaw. Recently, the significance of “SS” or “AW” has become increasingly floaty — as though to reflect the instability of our climate. (032c's Spring/Summer 2023 collection features coats, for example.) This was not quite the case, however, with “Close to the Hedge," KASIA KUCHARSKA's third collection, and the Berlin-based label's first to be presented during Paris Fashion Week. Aptly titled, it featured boldly colored and sculptural garments, ornamented with a horticultural vocabulary of florals and patterns derived from garden fences. “It’s a really summery collection, but we’re not calling it 'Spring/Summer,'” founder Kucharska relayed to 032c editor-at-large VICTORIA CAMBLIN at the brand’s showroom on Rue Notre Dame de Nazareth. “It’s simply ‘collection number three.’” This concord-discord dynamic is a through-line in the designer’s work and finds expression in the brand’s core material and motif: lace, a kind rendered in latex and developed with cutting-edge technologies that both defy and play with delicate fabric’s heritage.

The exact origins of lace are disputed by historians, but the fabric began to appear in paintings in the late 15th century. One can observe the material on the collar of a priest pictured in Hans Memling’s La Vierge et l'Enfant entre saint Jacques et saint Dominique, which currently hangs at the Musée du Louvre – just a short walk (and several technological revolutions) away from the storefront where buyers and journalists encountered “Close to the Hedge.” The painting provides a synecdoche for our associations with lace, which tends to be filed at a chasmic remove from the contemporary, or at least stuffed in the garderobe of your geriatric relations. But on the relative scale of textile history, and in keeping with the collapse of the fashion’s timeline, the 15th century is really just a season ago.

Historians believe Memling grew up in Mainz in the 1400s, a biographical detail he shares with Johannes Gutenberg, whose invention of metal movable type introduced printing to Europe. The printing press spread rapidly, fostering the invention and cultural production we associate with the Renaissance. Lacemaking exploded alongside publishing, because the accelerated distribution of images and ideas meant that fashions, and instructions on how to reproduce them, circulated fast, too. Lace’s popularity at court made its way to the colonies. The web-like textile crossed oceans, entangled with the very notion of European modernity.

The origins of lace can thus be linked to the development of the printing press. Naturally, as manufacturing technologies have evolved, so have production techniques. Machine-made versions of most types of hand-made lace have existed since the 19th century, and today lace patterns are digitally, even algorithmically, designed. Traditional printing processes are used to make electronic devices, and 3D printers are used to make just about anything. Compellingly, Kucharska’s label, which the designer operates in collaboration with fellow Universität der Künste alumni Wanda Wollinsky and Reiner Törner, is an experiment in both mediums. The latex lace at the core of their garments is both materially printed and a printed material – that is, what we call "print" is both a means of production and a design element – and results from a combination of historical study and future-facing research. The patterns begin by hand, pencil to paper. Then they are digitized and modeled into sculptural forms, realized in latex by 3D printers as layerable bralettes and bodysuits, opera-length gloves, bloomy overgrowths on Nike co-branded shoes, even a wedding gown.

The nuptial look and the brand’s low print run, as it were, bring the ambitious “Close to the Hedge” solidly toward a logic of haute couture. The sneakers and accessories keep things down to earth. Sometimes, Kucharska’s creations are quite literally in the soil. In one trial, the team left acid-green briefs in the dirt in their studio courtyard to see how the lace would respond to the elements. The panties did not biodegrade, but they did disappear. “We hope someone took them home and is wearing them,” said Wollinsky. The DIY approach to production matches the scalability of the operation, which is neither trad nor techno, conservative nor accelerationist. And as the clothes themselves physically evolve – the neon dyes fading as they oxidize, the latex off-gassing the smell of its own production just as freshly printed magazines do – so does the brand.

Victoria Camblin: One of the first things you said when I first came to the studio was about scaling up. That's a big part of product development. With a lot of industrial processes, there's a sweet spot where there's one process you can use if you're making less than a certain amount, but then when you increase in volume it doesn't make sense anymore pricewise.

Kasia Kucharska: With every product we make, the price is made upon how long it takes to print. And every piece takes the same time.

VC: So, making three is the same as making 3000?

KK: Yes.

Reiner Törner: You just need enough machines to do it, of course.

KK: I mean, it would be nice if it could be cheaper when you order 3000.

VC: In terms of scalability, that is a game changer – it means that you're never making these weird calculations. You could increase your output exponentially overnight without changing your production process or materials.

RT: Exactly. And the quantity needs to go up, always!

KK: It's a very labor-intensive process, which cannot be simplified. You just have to do it. You have to print piece by piece. We also do a lot of print on demand. We don't keep that much stock, and we can quickly reorder.

VC: That makes for a nice environmental narrative, too. There’s no waste due to overstock. Maybe it doesn’t biodegrade, but you'll have it forever!

KK: Exactly. It's indestructible, and we only make what we need. If you take care of it, you can have it forever. It is recyclable, that's for sure, but the more interesting thing for me is really biodegradation. There is one pair of underwear that we left outside in the courtyard to see what would happen to the material. We don’t know where it is anymore.

VC: Latex is tree sap, right?

KK: Yeah. It's the milk from the tree. There's also a difference between natural and synthetic latex.

RT: There are always additives that you put into latex. Like in cars, the wheels used to be made from natural latex, but now they are synthetic latex. But condoms are still made from natural latex, for example.

VC: Does synthetic latex also have the same property as natural latex where certain oils eat through it? This is a “sex ed” thing they taught in high school in the 1990s, where they would do a demonstration with a condom and put Vaseline on it and show it breaking because the chemical reaction eats through it. “Always used water-based lube, kids.”

RT: There are a few materials that damage the fabric, actually. I'm not one to talk about all the negative properties of latex, but some metals can also be bad for it. Gold, for example. If you touch the latex with gold, it can corrode or get a brown color. That also means there are things that you can do with that.

VC: You can oxidize it on purpose?

RT: Absolutely. Like, you shouldn’t put it on metal hangers, even though we sometimes do.

KK: You shouldn't do that, and you shouldn't put it in the sun.

RT: Some plastics, like the kind used for plastic bags, contain softeners that will damage the material too. So, there are plastic bags that you cannot use with our manufacturer to pack the clothing – we always send our products in specific bags that don't have plastic softener in them.

VC: I love nerding out on this technical stuff. I learned last year that because rubber trees take a long time to grow, the destruction of rubber plantations was a military tactic used in the Pacific Theater in World War I, to fuck over whoever ended up taking a given island. You didn't want the enemy to end up with this valuable and hard to cultivate export. The resulting shortages led the military to develop synthetic alternatives between the wars. So there’s a whole history of modern industrial warfare connected to materials like latex or neoprene. Actually, where is rubber sourced mostly, these days?

KK: Organic? Mostly Malaysia and Thailand.

VC: Which one’s more expensive: organic or synthetic?

KK: I would say natural is. We have nothing to do with synthetic latex, though probably it would be cheaper if we did. Otherwise, they couldn't make so many car parts and tires with it. Latex is actually a really expensive material.

RT: It's really expensive.

KK: And you can't do many trials. Once it dries, it's there forever.

RT: But there's also so many things that you can do with it. And when we are talking to the people that we work with, we’re developing new processes in real time and discovering new things you can make.

KK: Yes, for example, there are haptic devices that change the structure of the sheets. You can emboss them, you can even have the texture of snakeskin. There's so much you can do with all the different effects, there’s so much potential in these printing machines – even though they’re mostly just being used to print glue onto boxes for shipping, so you can put them together faster. No one wanted to print latex before, because there was no purpose for it. Then we come in and we're like, "let's print clothes." And we really work with an end-product in mind. We want products, that's always the purpose. There's not so much time for experimenting.

VC: Things move quickly in the industry, too – no matter what material process you’re using. How are you approaching this release on the “fashion calendar”?

RT: I mean, we have always talked about it. One thing we've done with past collections that has worked really well is to release products that are very flashy, very Instagramable.

VC: They definitely look really good on the internet.

RT: The latex photographs amazingly. That’s people want to have it. But we really wanted to have people come and physically interact with things – but not in fashion shows where you just look at things from afar.

KK: We're not going to do a fashion show. But we do want to see if the system works.

RT: We want to have interactive events where people can actually do something – and we always want to be close to someone who's actually into the product. Because the product already is already so artificial, and the appeal of that is so strong, it’s interesting to do something “in real life” – in real contact with the material.

KK: We’ve been joking about a game night.

VC: And the latex product is like another party guest – the life of the party?

KK: I like that. I mean, I do feel pressure to do more traditional presentations, because of course buyers have to have their schedules. They’re like, "send us your FW 2022 look book." And I'm like, "Ok, here's our look book."

VC: It’s so strange that we are back to that now. Even before COVID, everyone was very much moving away from the seasonal calendar. It became a “thing” to not be on the calendar or do separate men’s and women’s presentations. Like, there's a logistics crisis now. Everyone's sick all the time. If there was ever a time to change it up it would be now, but now even the people and brands who emphatically weren’t doing seasonal releases are going hard on the calendar.

RT: We totally went backwards. It's bizarre – everybody was talking about how everything needs to change, and now it's just like, "Thank fuck COVID is over, we can just do whatever.” Or double down on how it was.

KK: The pressure is a real thing. I felt like, “We should do something in September; we should be a bit more on it.” But then I got excited, because we’d never met our customers IRL. So, this is about meeting up, finally.

VC: Well, if it's the party guest, then you can drop into somebody's affair – you don't need to live there permanently.

KK: Exactly. Instead of doing something for the sake of this schedule and ending up with just a slightly different version of what came out last time, with only carry-overs and a change of color or a little accessory somewhere.

RT: We want to be satisfied about the product as well, about what we do. And we want to do new things as well.

KK: Being designers is what we do best. We are not like ...

RT: Salespeople.

KK: And the marketing – that's not our passion.

VC: Which is where the calendar comes from: marketing.

KK: It's marketing. And we really want to work on the product and try things out and release things when we think they are ready. Of course, we have been doing the wholesale ourselves. Because we do everything ourselves – sales, all of it, we do it in house. But we are designers, and we are very passionate about that.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

- Photos: Kasia Kucharska

Related Content

BERLIN by RICCARDO TISCI

MONA TOUGAARD in “The Whole World Glows Outside Your Eyes”

Now in Berlin (if not quite *on view*): “Masculinities – Liberation Through Photography”

The Power of Three: THOMAS LOHR’s Techno Sexual Fashion Photography

MARIACARLA BOSCONO in “I do it exceptionally well. I do it so it feels like hell.”

“Modern Since 1973”: CLAUDIA SKODA Tells Her Story

ALEXANDRA BIRCKEN: Bodyrevolt

“The Berlin Archive 2009–10” by Cyprien Gaillard