Now in Berlin (if not quite *on view*): “Masculinities – Liberation Through Photography”

|Wes Del Val

Because I’m American, and most of the world is rightfully socially distancing itself from us, I missed Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography at the Barbican in London this summer. If you’re like me – and also failed to catch the exhibition’s second iteration in Berlin this fall, before Europe’s second wave shut down the Martin Gropius Bau – I have good news: there’s a catalogue.

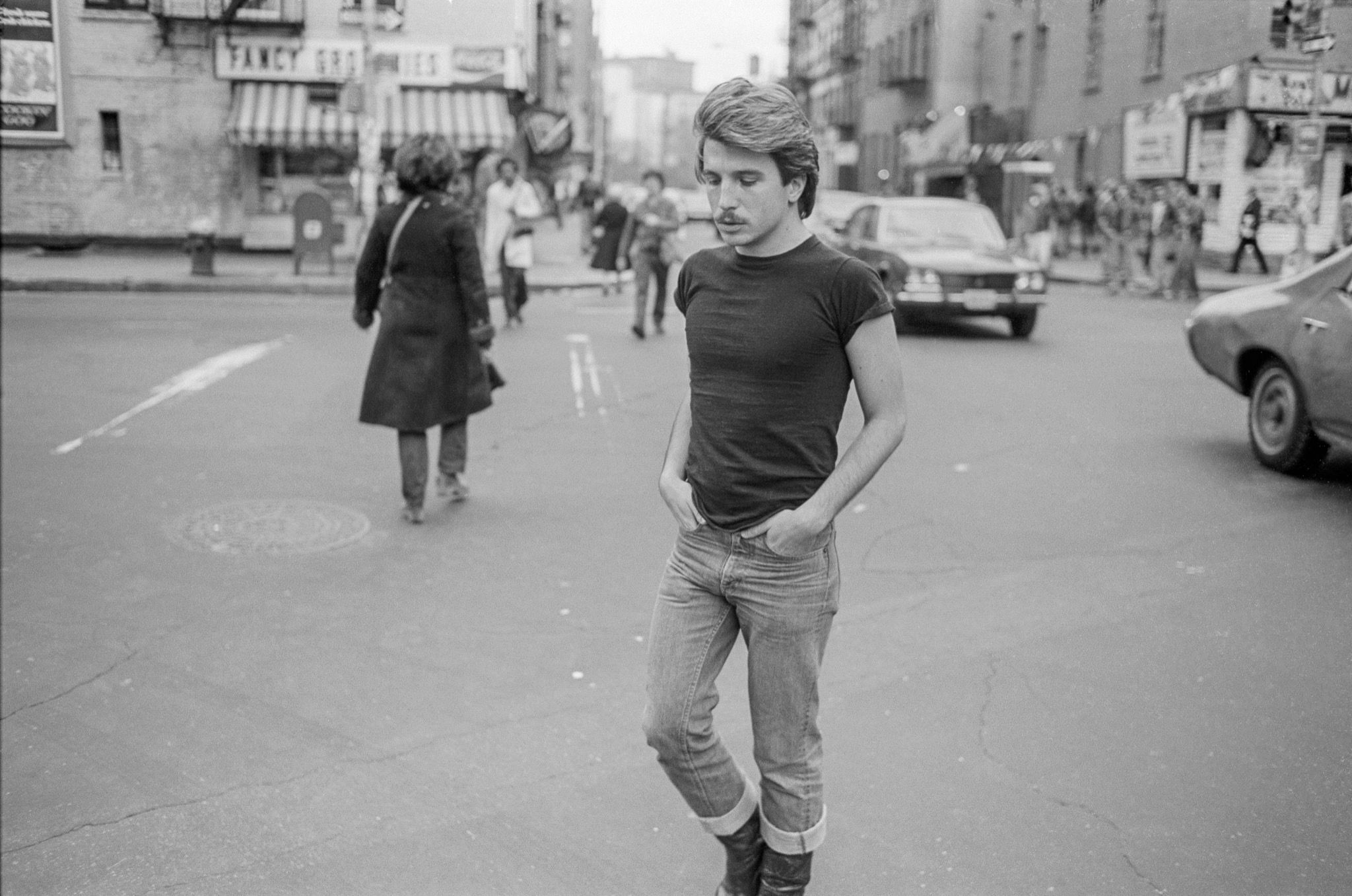

I’ve seen a PDF of the whole book, designed by The Bon Ton, and it is filled with a fabulously diverse range of images from the past five decades, all examples of “masculinity” and its ever-expanding (thank god) definitions. (If you happen to get your hands on a copy, turn immediately to these, my favorite pages: 59 for John Coplans, 72-75 for Wolfgang Tillmans, 94-97 for Catherine Opie, 138-141 for Andrew Moisey, 168-171 for Hans Eijkelboom, 198-201 for George Dureau, 212-217 for Hal Fischer, 238-241 for Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and, of course, 278-281 for Ana Mendieta.) To further stave off my hunger for star-studded thematic museum photo shows, I reached out to Masculinities’ curator and catalogue editor ALONA PARDO, whose project explores “how masculinity has been experienced, coded, performed, and socially constructed” – a “murky premise,” Pardo explains, that provided the starting point for a representational survey of photography and film from the 1960s to the present.

Wes Del Val: What made the question of masculinity important to address, now?

Alano Pardo: This is a timely exhibition, and it comes at a moment when men and masculinity have become an important cultural flashpoint. However, while men and masculinity find themselves under the microscope as never before, it is not entirely clear what “masculinity” means – shadowy definitions are infused with media-friendly narratives of common sense and pop psychology.

Given the expansive nature of the subject, it was necessary to put in place a coherent framework while embracing a plurality of voices and ideas. In light of this, I decided early on that the show should really commence in the postwar period. This was a moment when the characteristics and power dynamics of the dominant masculine figure—historically defined by physical size and strength, assertiveness and aggression—though still pervasive, began to be challenged and transformed. The global nature of the landscape we wanted to chart was also critical to the show, which complicates received notions of masculinity by bringing into play representations from across multiple places and spaces. For instance, a small sub-section exploring the significance of the military in the construction of masculine identities includes work by Wolfgang Tillmans, Lebanese photographer Fouad Elkoury, and Israeli artist Adi Nes, as well as photographs of Taliban fighters that photojournalist Thomas Dworzak found in Kandahar while covering the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

At a time when the question of gender is often seen as concerning women, it is ever more urgent that we understand men and boys as gendered – or, more precisely, that we ask what it means to be, or what is required to become, a man or a boy. Many of the works in the show pry open the relationship between men and masculinity by highlighting how masculinity is socially constructed and culturally configured. Equally, studies by scholars including R.W Connell challenge and problematize appeals to biological certainties and psychological inevitabilities—ideas often expressed in phrases such as “boys will be boys,” or “man up.” This field of research started to capture how being a man was shaped by race, ethnicity, age, class, disability, sexuality, and culture, and as a result highlighted the importance of thinking about masculinities in the plural rather than “masculinity.”

Social media, because of its ability to share and comment a diversity of representations, and to catalyze movements such as the internationally recognized force of #MeToo certainly, has been instrumental in chipping away – though many would have preferred axe swings – at “toxic masculinity.” Did you get to address this evolving terminology – the words as well as the images?

In the wake of the #MeToo movement and the upsurge in men’s rights, traditional masculinity has become a topic of impassioned debate, and endless column inches have been devoted to exploring ideas around “toxic” masculinity. While the show can be read through the optics of the #MeToo movement, it also needs to be viewed against the current resurgence of far-right ideologies and a so-called “masculinist nationalism” characterized by male world leaders shaping their image as “strong” men.

One of six exhibition chapters, the mischievously titled section “Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space” invites the viewer to reflect on the construction of male power, gender and class. Two ambitious, multi-part works – Richard Avedon’s The Family (1976) and Karen Knorr’s Gentlemen (1981–83) – focus on typically besuited white men who occupy the corridors of power, while simultaneously foregrounding the historic exclusion not only of women but also of other marginalized masculinities: Black or brown bodies and members of the LGBTQ community. Male-only organizations have often served as an arena for the performance of “toxic” masculinity, as chronicled in Andrew Moisey’s startling The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual (2018), which charts the misdemeanors of fraternity members alongside an indexical image bank of US Presidents and other leaders of government and industry who have belonged to these groups. Richard Mosse’s 2007 film Fraternity takes another tack by painting a portrait of male rage that is both playful and profoundly sincere.

You also have a chapter called “Reclaiming the Black Body” – the only one directly related to race in theme.

“Changing representations of Black men must be a collective task,” bell hooks writes in Black Looks: Race and Representation. Given the social and political shifts that took place in America and elsewhere through the late 1960s, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the struggles of the Black Power movement, and the decolonization of broad swathes of British and other European colonial states, and in light of the current Black Lives Matter movement, it is critical to reflect on how Black masculinity has “threatened [the] power and privilege of white masculinity that has been the symbol of patriarchal order,” and to explore how artists have, over the last five decades, systematically offered a counter-representation of the Black male experience.

Ultimately, the works presented reflect on how Black masculinity challenges the status quo. Samuel Fosso’s playfully staged self-portraits, taken in his studio during the 1970s, appear alongside Kiluanji Kia Henda’s fictional scenarios, in which the artist adopts the personas of African men of power. Hank Willis Thomas’ complex series Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America (2005–08) redeploys magazine adverts, largely culled from titles such as Jet and Ebony made between 1968 – a pivotal moment in the struggle for civil rights – and 2008, which witnessed the accession of Barack Obama to the US presidency. By digitally stripping the ads of all text, branding, and logos, Thomas draws attention to the ways in which corporate America has commodified the Black American experience, while simultaneously perpetuating and reinforcing cultural stereotypes. These are also challenged in Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged color photographs, which play with popular aesthetics and appropriate the visual codes popularized in the pages of Jet and Ebony, alongside other cultural references. Toying with photography’s status as document, Lawson’s complex images, which explore intimacy, affinity, sexuality, and relationships, examine how Blackness is represented and how her subjects are often “idealized (in their physical beauty) and pathologized by the culture (as symbols of violence or fear).”

The subtitle of the show is “Liberation Through Photography,” and the catalog provides enlightening essays and a helpful, welcome glossary of terms. Regarding the image versus the word, which mode of communication, in your opinion, has more capacity today to take notions of masculinity in new, positive directions?

In addition to questioning the agency of photography, the subtitle can be read as being ironic, begging the question: does masculinity really need “liberating”? I would argue that as a gendered construct it certainly does need to be liberated, from societal expectations and gender norms.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, combining words and photographs had become a genre of art photography with a wide and varied practice – ranging from simply writing on photographs to the first experiments with the digital collaging of word and image. At a time when the “truthfulness” of photography was being questioned, the photograph had already outstripped the word as mass media’s preferred descriptive system. We now live in an image-saturated world with an increasingly short attention span, and we are all simultaneously becoming more visually literate – armed with the ability to decode the signifiers embedded in images. So I do feel that images play a critical role in how we encounter the world.

In your introductory text in the book you make clear that masculinity cannot be fully understood unless women’s masculinity is considered. The vast majority of the images in the book are of men shot by men, followed by men shot by women, followed by a series of a woman shooting women. I think the only example of a photograph of a woman shot by a man is Robert Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Lisa Lyon. Why have so few men sought to explore and capture female masculinity?

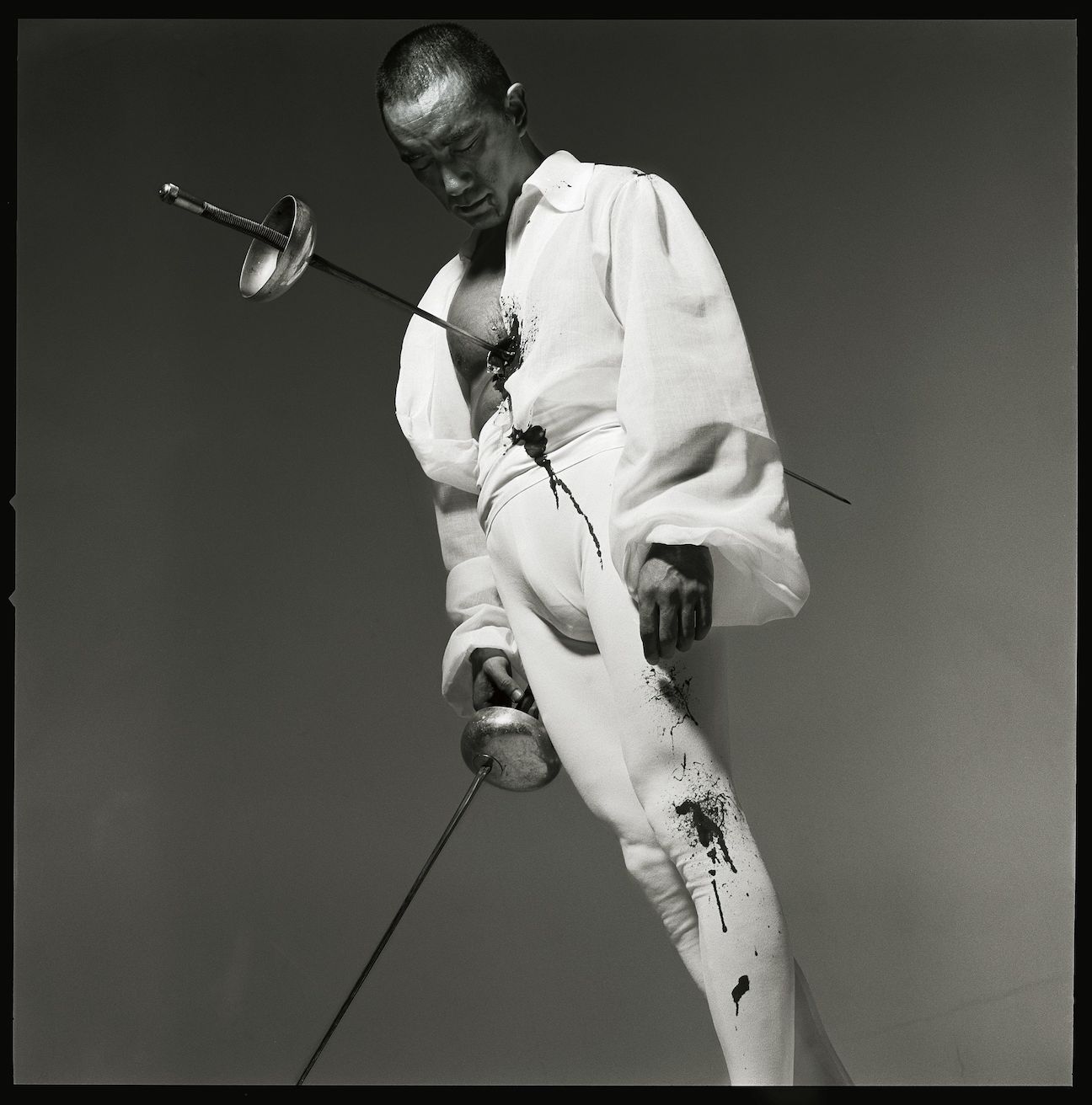

I deliberately sandwiched the image of Lisa Lyon between two of Mapplethorpe’s studies of Arnold Schwarzenegger. The muscular male body is explored in the photographer’s full-length black and white portraits of Schwarzenegger, who is shown in his underwear performing poses in the artist’s studio in 1976, the year after his retirement from professional bodybuilding. The curator Christopher Bedford has argued that Mapplethorpe here transforms a “heterosexual male athlete into an object of his desire,” encouraging the viewer to linger over Schwarzenegger’s self-created musculature and bodily excess. In contrast, when in 1979 Mapplethorpe was introduced to Lisa Lyon, a female bodybuilder who had won the first Women’s World Pro Bodybuilding Championship earlier that same year, he was instantly struck by her muscular physique. “I had never seen a woman like that before. It was like looking at someone from another planet,” he is quoted as saying. Mapplethorpe, fascinated by the way her muscular physique directly challenged and disrupted the existing visual record, was freed to explore gender ambiguity and an enigmatic interplay between gender and masquerade, masculinity and femininity, strength and vulnerability. As Mapplethorpe’s biographer Patricia Morrisroe has written, Lyon “saw herself more as a sculptor who used her own body as raw material. Her meeting with Mapplethorpe, then, was serendipitous, for she was searching for a photographer to document her ‘work-in-progress.’”

Which artists or works were great discoveries for you in making the exhibition?

There are numerous artists in the show whose work I have admired for a long time, such as George Dureau and Tracey Moffatt, whose work is rarely seen in the UK. There were of course some discoveries along the way, notably Elle Pérez, a gender non-conforming artist whose work focuses on America’s gay, gender variant, transgender, and genderqueer communities. We’ve included two works, t and gabriel, that Pérez describes as forms of self-portraiture, and that are concerned with the artist’s relationship to their own body, their queerness, and how their sexual, gender, and cultural identities intersect and coalesce through photography. t presents an image of a hand holding a small vial of testosterone, a hormone closely associated with men – although it is present in women too – and that can be taken by someone transitioning from female to male. In this work, the essence of masculinity is made tangible, able to be grasped in a hand.

The exhibition originated in London and is currently traveling in Berlin. Does the European context change the tonality of the exhibition in terms of how masculinity is viewed in different cultures?

The politics of identity are under daily scrutiny by broad swathes of the European population. As the rights of LGBTQ communities are being increasingly challenged by repressive political ideologies in countries such as Hungary and Poland, I hope the exhibition attests to the performative and unfixed nature of gender that is shaped by cultural and social forces.

Credits

- Text: Wes Del Val