ALEXANDRA BIRCKEN: Bodyrevolt

|Oliver Koerner von Gustorf

The membrane between surface and substance, materials and morals, is thin – if it exists at all. Using motorcycles, knitwear, gimp suits, and twigs, the artist Alexandra Bircken explores such ambiguity in our politicized world.

Bodies in Amazon warehouses, in juvenile detention centers on the border between Mexico and Texas, in the Mediterranean, floating. Bodies treated like cattle or flour sacks, trafficked for sex and enslaved for labor. Bodies falling from the heights of the burning Twin Towers, clinging to the last military planes leaving Kabul. Bodies climbing the Berlin Wall and onto rescue ships, pulling themselves up the façade of Washington’s Capitol building. Bodies that revolt, struggle, fail, fall, stay down, decay, wither. Bodies that emerge from wombs, eggs, incubators. An industry of bodies. Hedonistic, precarious bodies that hang out in dark rooms and techno clubs; that knock themselves out, get fucked up, fall into K-holes, allow themselves to be extremely closed off or opened up; that take something and give, maybe want to be all thing, all feeling, like the Useless Man the London band sang about in the 1990s: bootlicking, piss-drinking, finger-frigging, tit-tweaking, love-biting, arse-licking. Bodies.

Alexandra Bircken’s installation Fair Game at Berlin’s KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art is part Terrordome, part Pleasuredome. When I stepped into the boiler house of the former brewery in Neukölln on a late autumn afternoon, the setting sun was shining through the glass façade, bestowing the scene with something sacred. Dust particles and fluff swirled through the air; some settled onto black latex figures scattered on the concrete floor like limp, boneless bodies, massacred. Derived from diving and protective suits, or extreme rubber fetish, some of these forms were adorned with embroidery suggesting eyes, muscles, organs, a spine. On others, there was an ostrich egg where the uterus usually is, a patterned piece of t-shirt or panties hung out of a small hole in the shell, something worn that you leave out on the street or put in a box at a flea market. In front of the wall at the back of the space were handblown, hand-painted “incubators,” as Bircken calls her glass cocoons reminiscent of Murano glass, art deco, and such horror films as Alien or Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Yet what was hatched within these cocoons were not aliens but twisted fabrics and stuffed animals. Bircken fitted some of the glass containers with hat-like knitted bandages, as if they might get the chills, like living beings that need to maintain their temperature.

Black beer barrels and loudspeakers were piled in the center of the room, expelling a techno-like collage of noises, fragments of recorded speech, and a rhythm reminiscent of an artificial heartbeat, turning the hall into a giant, breathing, pulsating organism. Set in this scene are Bircken’s empty figures, which received the contours of shoulders, or were brought into an upright position with the assistance of built-in clothes hangers. The hooks of the hangers that protrude from their necks make them look like halves of cows or pigs in meat factories – the difference being that these effigies evoke the shadows, or remains, of people that are being processed. Bircken has hung them wherever the opportunity presented itself: from screws protruding from the wall, from pipes, ladders, steel girders, rusted angles; and all the way up, hanging from the dome atop the tower, in various constellations, sitting, standing, kneeling, climbing, alone or in groups. In front of the peeling walls or tiles, the various materials and grid-like structures in the hall, the figures developed a painterly, almost abstract aspect. In some places, the black figures appeared to be two-dimensional, flat, like blots on a Tachiste ink drawing; elsewhere they seemed incredibly physical. A suspended ladder with rungs of bone led up to the ceiling, with its huge skylights. Looking up felt like standing inside an industrial take on one of Giambattista Piranesi’s architectural fantasies. In 1761, the Italian engraver and architect created the etching series Carceri d’invenzione (Imaginary Prisons), a surreal world of penitentiaries where the viewer is at the mercy of intermediate spaces, places where there are no dungeons, just gigantic voids, gates, arches, stairs, and ladders that lead one astray or into a wall, making any orientation impossible. With his works, Piranesi wanted to evoke a combination of loneliness and monumentality.

Bircken’s installation would also convey this overwhelming sense of isolation, were it not for some of the works’ last, desperate attempts to establish community and give birth to new life. The press text conveyed that the installation was partly inspired by Samuel Beckett’s short story “The Lost Ones” (1971), wherein 200 naked bodies are locked in a large semidark cylinder called the “abode.” They keep trying to find a sense of orientation or an exit to escape with ladders. Beckett’s text can be read as an existential parable of a society incapable of changing, of establishing fraternity, a society that instead performs the same absurd acts over and over, until the search for escape is abandoned and life mercilessly fades away.

The central figure of the exhibition was The Tourist, the only body that is modelled and colorful in Bircken’s endgame. It is a techno-spiritual hybrid – part healer, part assassin. Instead of a head, antlers made from tubes perch on the shoulders of the doll, which is wearing the protective padding of an American football player. The torso, arms, and legs are fitted with knittings in a deconstructed pattern of color blocks. The feet are encased in chunky Plexiglas clogs.

In one hand, Bircken’s androgynous creature holds a blue canvas bag that has

the logo of a tourist resort on the Bavarian Ammersee printed on it; a huge sword is in the figure’s other hand. The sculpture creates relationships between wokeness and rage – between hippie hipsters scurrying through Berlin Mitte, Williamsburg, or Daikanyamacho, and the shamanic, self-assembled looks of the QAnon and Querdenker movements. Upon reflection, this figure also reminds me of something exasperating. It reminds me of my own anger and frustration that I try to smoke out and meditate away; it reminds me of my efforts to give myself a scientific, political, and spiritual education, to understand more, to become more open, more compassionate, even while I stand like an ignorant tourist in the middle of the global carnage I am a part of.

“That so many shamanic or animistic approaches are currently popping up in art isn’t due to esotericism alone, it’s also due to the search for answers and finding other ways to speculate,” Bircken told me. “The Tourist can be read as a warrior. Whether she’s ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is hard for me to say. She’s holding a saber in her hand, so it might appear as if she has lynched the latex figures.” A few days after my visit to the exhibition, we spoke via Zoom. The artist, who was born in 1967 and has exhibited internationally in solo and group shows including the 2019 Venice Biennale, had just returned to her studio in Berlin from a brief vacation. She was heading to Paris the next day with her class at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where she has been a professor since 2018. Bircken is a very busy person. Simultaneous to her exhibition at KINDL, the most extensive showcase of her work to date was on view at Museum Brandhorst in Munich. Titled Alexandra Bircken: A–Z, it illuminates the most central theme of the artist’s work: the skin as a membrane, as an organ, as clothing, and as a boundary between inside and outside. Bircken creates organic-technoid constructions out of textiles, machine parts, wood, steel, and latex, which critically question and radically expand notions of corporeality and limits.

When we spoke, Bircken sat in front of her screen at a huge table, wearing a beautiful jacket patterned with countless brightly colored squares on a white background. Seeing her sweater, I couldn’t help but think about Bauhaus, Russian Constructivism, and the Wiener Werkstätte – about movements of utopia and reform. Yet, she radiated something completely undogmatic and is totally approachable, not consecrated at all. She explained that the figure of the tourist was partly inspired by a passage in Heiner Müller’s Hamletmachine, namely, the soliloquy by Electra, the great avenger of Greek mythology: “Here speaks Electra. In the Heart of Darkness. Under the Sun of Torture. To the Metropolises of the World. In the Names of the Victims. I expel all semen which I have received. I transform the milk of my breasts into deadly poison. I suffocate the world I gave birth to.” The passage ends with the sentences: “Down with the joy of oppression. Long live hate, loathing, rebellion, death. You’ll know the truth when she walks through your bedroom with butcher’s knives.”

"It reminds me of my own anger and frustration that I try to smoke out and meditate away; it reminds me of my efforts to give myself a scientific, political, and spiritual education, to understand more, to become more open, more compassionate, even while I stand like an ignorant tourist in the middle of the global carnage I am a part of."

References to art history, mythology, ethnology, natural sciences, technology, and spiritual practices can be found throughout Bircken’s work. Yet, based upon her comments about her work, one must be careful about projecting a single narrative onto it: “There’s the body, but it’s also a suit, clothes. This ambivalence is central to the works, as is a certain functionality. In the KINDL space, the latex figures are hanging in a row at the ceiling, and it’s as if they had just been sewn in a factory, or [are] like clothes hung up in a row in a closet. There are certain formal settings where the latex figures become gestures or characters, and others where they look like uniforms or an outline, a cut-out surface.” I asked her whether you could say that her artistic practice is materialist in nature. Yes, you could certainly say that, she replied.

Her works often begin not with a story or image but with a reaction to certain situations. She explains that the first iteration of Deflated Figures was created for an exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield – the museum located in the West Yorkshire birthplace of legendary sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903–75): “That was the first time I worked with the ladders the latex figures ‘climbed up.’ The museum’s building is this really great design by Chipperfield. The room’s corners all have different angles. You have to constantly calibrate yourself in the room; it’s a very strange spatial feeling. You can’t really figure out how to orient yourself. It has a luminous ceiling and a kind of shelf that’s eight meters high. Up there’s where the ladders led. I purposely chose black to create the maximum amount of contrast with the white cube.”

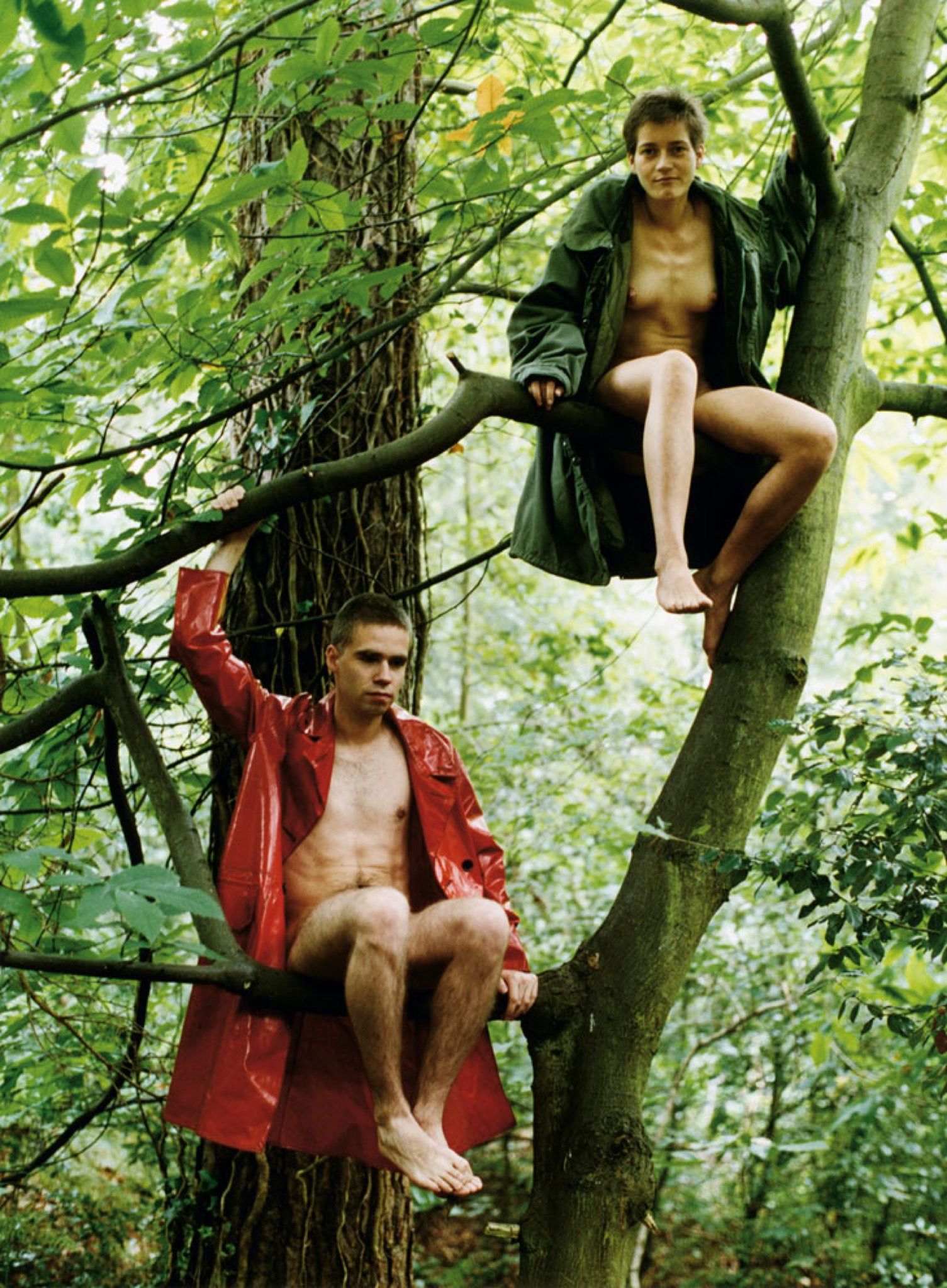

That she can be so bold and precise with a wide variety of materials might be because she came from fashion and club culture. With her lifelong friends, fashion designer Lutz Huelle and photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, she left Remscheid, in the Rhineland, and travelled to London. There, she studied fashion and graduated from the University of the Arts London’s Central Saint Martins – in the very same experimental study course that the designers Alexander McQueen and John Galliano attended. It was the era of early digitalization, of geopolitical and technological reformations, in which political fronts and social systems dissolved, were upended, and new connections were formed – themes that would characterize Bircken’s later artistic work. In fashion, it was the era of deconstruction and material experiments, embodied by Martin Margiela, who recruited Bircken after graduating. Her later approach to volume, bodies, emptiness, and layering was certainly shaped during this time.

In 1995, Bircken and Huelle were immortalized by Tillmans in the iconic photo of gender-bending Lutz & Alex Sitting in the Trees, where both are naked except for their latex and raincoats. “Although I’m a cis woman and straight,” Bircken says, “I never fit into that girlie-girlie mold. It didn’t match my physical perception of myself. I met Lutz and Wolfgang really young. I was 15 when they came out in Remscheid. They were the first guys I was on the same wavelength with, and they helped me to realize that I don’t fit [the mold for] a certain type of woman.” Bircken says that this friendship made many of her issues disappear. “We discovered freedoms together. Especially with Lutz, who is a man but physically very similar to me. But then, where does this being

a man begin and end? Then he started wearing my clothes, and I wore his. We mixed it up and experimented. What’s the path, how do you want to be? Is there a path? What’s the status? How does it feel to wear leather pants, latex, the whole fetish gear, sports clothes, or floral patterns? All of that came up because of my encounter with gay men.” Questions of gender, belonging, and identity were raised with incredible urgency in the mid-1990s at the height of the AIDS pandemic – and they were also familiar questions in the gay clubs Bircken visited with her friends. The idea of changing your body with makeup or drag, the extravagant and outlandish costumes or fetish gear, and the extreme performances of this time cannot be reduced to hedonism alone: they were a reflection of queer and feminist revolts, first against Thatcher’s neoliberalism, and then against Tony Blair’s “Cool Britannia.”

“Clubs played a big role in the KINDL installation, of course,” Bircken told me. “The space at KINDL used to be a club, too. There was also the idea of installing something like a darkroom. Techno’s a black box and the complete opposite of a white cube. Techno always had something to do with the industrial and the dissolution of identity in the masses.” Performer, fashion designer, and club promoter Leigh Bowery was an important figure in her early London period, Bircken reported: “Especially because he kept reinventing himself in such a radical manner. He used clothing as a way of expanding and changing the shape of his body. That’s how he became a sculpture. In conventional categories, he made himself ‘ugly,’ a dimension I find extremely important today.” One can find clear references to Bowery’s practice in Bircken’s series New Model Army (2016) and the sculpture The Doctor (2020). Of south London club nights, Bircken says, “It wasn’t about being ‘beautiful’ with the stuff that was worn in the Fridge in Brixton. It was about being extreme and expressing yourself. Pushing the boundaries of your body to the limits. Sexiness was important, of course, but in a much less limited way than today. We wanted to explore material for what it was – leather, plastic.”

What “extreme” used to mean has now been somewhat forgotten. Bowery, who died of an AIDS-related illness in 1994, founded the legendary club Taboo, which Boy George and John Galliano frequented. Bowery was an icon of the scene, and the massive, six-foot-four Australian’s practice was something that could not be called “drag.” He created nightmarish and glamorous cyborg versions of social stereotypes: working-class women, socialites, middle-class housewives, gay salesmen, skinheads, fetish fans. Bowery upholstered himself as a creature of art, covered himself with latex or brocade, added protheses, plastered them with silicon and paint, pierced masks on his face. No one was safe during his performances. During a concert with his band Minty he suddenly went into labor on stage and “gave birth” to his partner Nicola Bateman, who had been tied up and worn by Bowery beneath his dress for the whole performance. He also emptied his bowels.

The shockwaves Bowery triggered were not limited to feces and taboo-breaking. They could be felt in the utopia he embodied. In 1990, Judith Butler declared in Gender Trouble that gender was no longer a given but a social, performative construct, constituted primarily through the repetition of speech acts. In the same year, Donna Haraway published her groundbreaking Cyborg Manifesto, in which she poses the fundamental question: “Why should our bodies end at the skin?” In this text, Haraway, a feminist historian of science, proposes an end to demarcations between animal, human, and machine, as well as between the natural and technological. Haraway’s project is a radical attack on the anthropocentric worldview, and on notions of family, gender, and reproduction. Her image of the cyborg is not a human-machine, but rather a mythical figure of thought that is meant to help redefine the relationships between society, science, and technology. For Haraway, cyborg bodies are “maps of power and identity.” The same could be said of Bircken’s sculptures and installations.

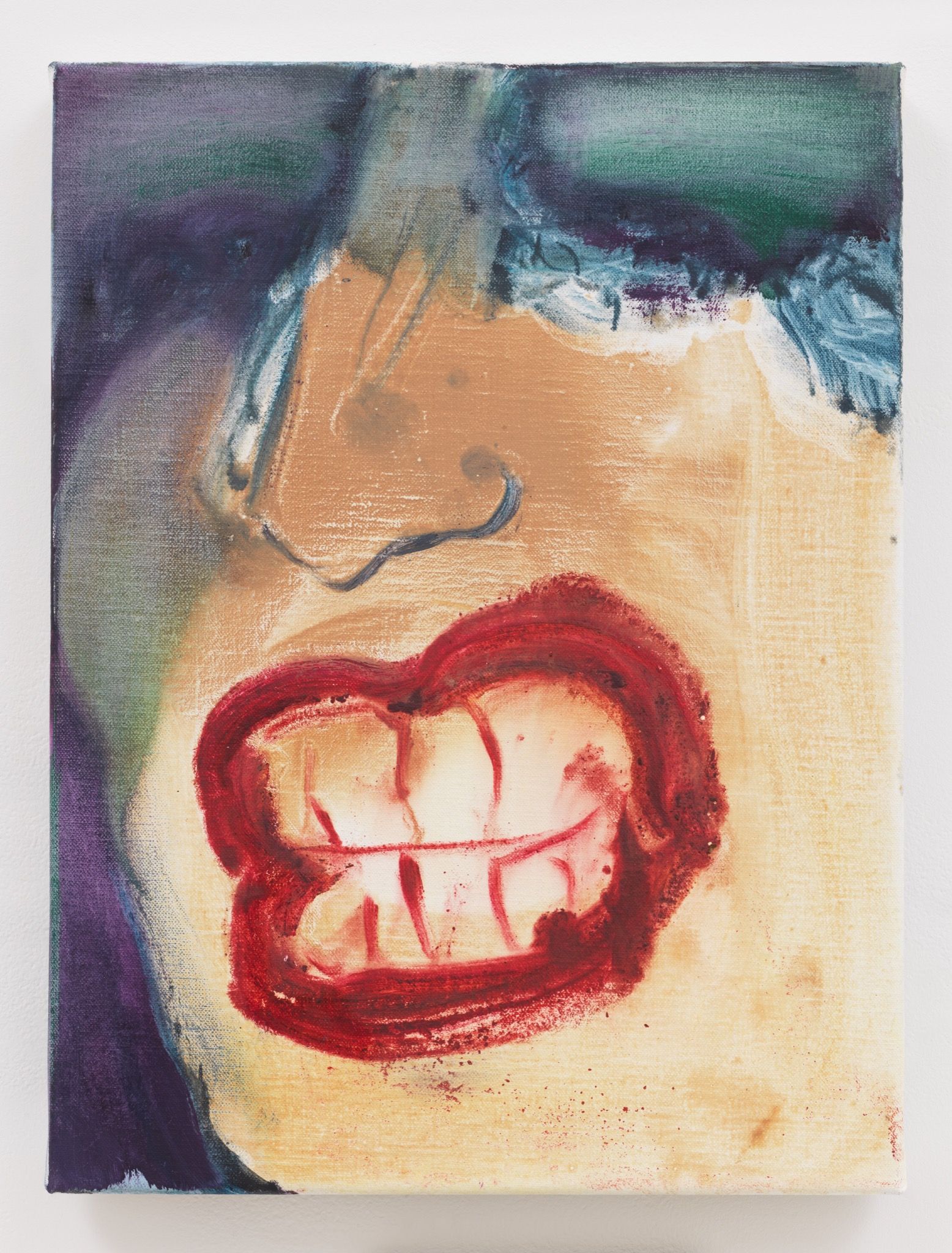

Her development as an artist may have been significantly shaped by her time in London, but it officially began with a solo show in 2004 at Galerie BQ in Cologne, where Bircken moved in 1999. Before that show, she ran her own fashion label with her partner at the time, Alexander Faridi, and later had a successful stint as a designer for Jean-Charles de Castelbajac in Paris. In her Cologne studio, she created objects “that didn’t require a body as a justification.” Some of her early works were sewn together from knitted and woven sections and stretched on a frame of twigs, but then Bircken started incorporating readymade objects into her work, such as clothes racks, plaster or concrete components, tailor’s dummies, motorcycles, and lattice structures from branches. She also activated the entire exhibition space as a bodily form. The retrospective at Museum Brandhorst featured a number of Bircken’s “signature works” – such as the motorcycles that are bisected or mounted like rocking horses, and the works made from motorcycle gear stretched out like roadkill or puffed up like Hans Bellmer dolls. There was also her placenta from the birth of her daughter in 2011, which Bircken first kept in the freezer and exhibited – during 2017, under the title Origin of the World – in a glass cube filled with formaldehyde, like a science specimen. The work takes its title from Gustave Courbet’s famous painting L’Origine du monde (1866), which shows the hairy vulva of a naked woman reclining, her thighs spread, her face not visible.

Whether they enthusiastically celebrate the fact that biological motherhood is finally being addressed in art or consider it to be totally reactionary for precisely the same reasons, reactions to Bircken’s placenta piece demonstrate how her work is often misunderstood. When she and I spoke, we discussed the time during which it was created – a time just before recent, bitter debates about transgender rights and feminism, which were fueled by Harry Potter author J. K. Rowling and radical feminists such as Germaine Greer. This faction postulates that only those who were born with a uterus are actually women. For them, equating with “real women” biological men who take hormones, have surgery, or still have their male genitals is yet another marginalization of the female experience, an example of female oppression, and a male-dominated attack on feminism. These very specific debates about biological sex have been important because they are closely related to the idea of “cancel culture” and to disputes about imposed political correctness, about what is “normal” and what is “elitist” or “decadent.”

One might think, I said to Bircken, that she is taking the position of a radical feminist who celebrates nature’s design. Bircken vehemently denied this suggestion: “Of course I was aware I was ‘taking something away’ from Courbet with this work, namely, the sovereignty of the title L’Origine du monde in his depiction of the vulva from a male perspective. I have to admit that [doing so] pleased me. Still, I think these gender discussions, these questions about who belongs and who doesn’t, are counterproductive. I’m more interested in dissolving these categories. I don’t give a damn whether the motorcycles I use to build my sculptures come from a man’s world or a woman’s world. I don’t see it as my job to represent a particular feminist stance; my work springs from a much deeper feeling.”

At that moment, it became clear to me how fatal it can be to understand Bircken’s work as a kind of illustration of ideas. Her work – which repeatedly brings to mind such artists as Robert Morris, Eva Hesse, or Isa Genzken, and which is anchored in the strategies of post-minimalism – does not deliver representative, symbolic experiences, but rather material ones. It does not signify anything; it simply is. And it is quite deliberately problematic; the problems condense in the materials. Bircken does not try to solve them, but to elaborate them. Like all of Bircken’s other pieces, this placenta work should not be understood as a commentary, but as a statement, something that raises questions “as matters of fact.” A critic from a major German newspaper recently accused her work of not being suitable for the post-Covid-19 era, as it fails to call forth utopia, offers no joyful messages about the experience of birth, and is not really “designing” the present. Thank God.

Fortunately, Bircken does not convey any didactic, safe, smart-aleck art statements about the state of the world. Fortunately, she looks at the discourse more from a cyborg/alien/ shamanic perspective, much like her character of the tourist. This perspective is not so much the position of a feminist or institutional critic who aspires to be on the “correct” political, moral side. Instead, it is like an alien on a planet that is truly new and foreign to her. Thank God, she remains compassionate toward, yet alienated by, our trouble, our contradictions, and our antagonisms. Bircken’s materialist, speculative practice does not try to normalize or “fix” our relationships, never mind the attempt to neatly wrap them up in a story.

As Haraway says: “We are speechless now, in the face of earthly destruction ... but good thinking often happens exactly when we are speechless.”

Credits

- Text: Oliver Koerner von Gustorf

- Translation: Shane Anderson

- Portraits: Thomas Brinkmann and Wolfgang Tillmans