“Modern Since 1973”: CLAUDIA SKODA Tells Her Story

|Adriano Sack

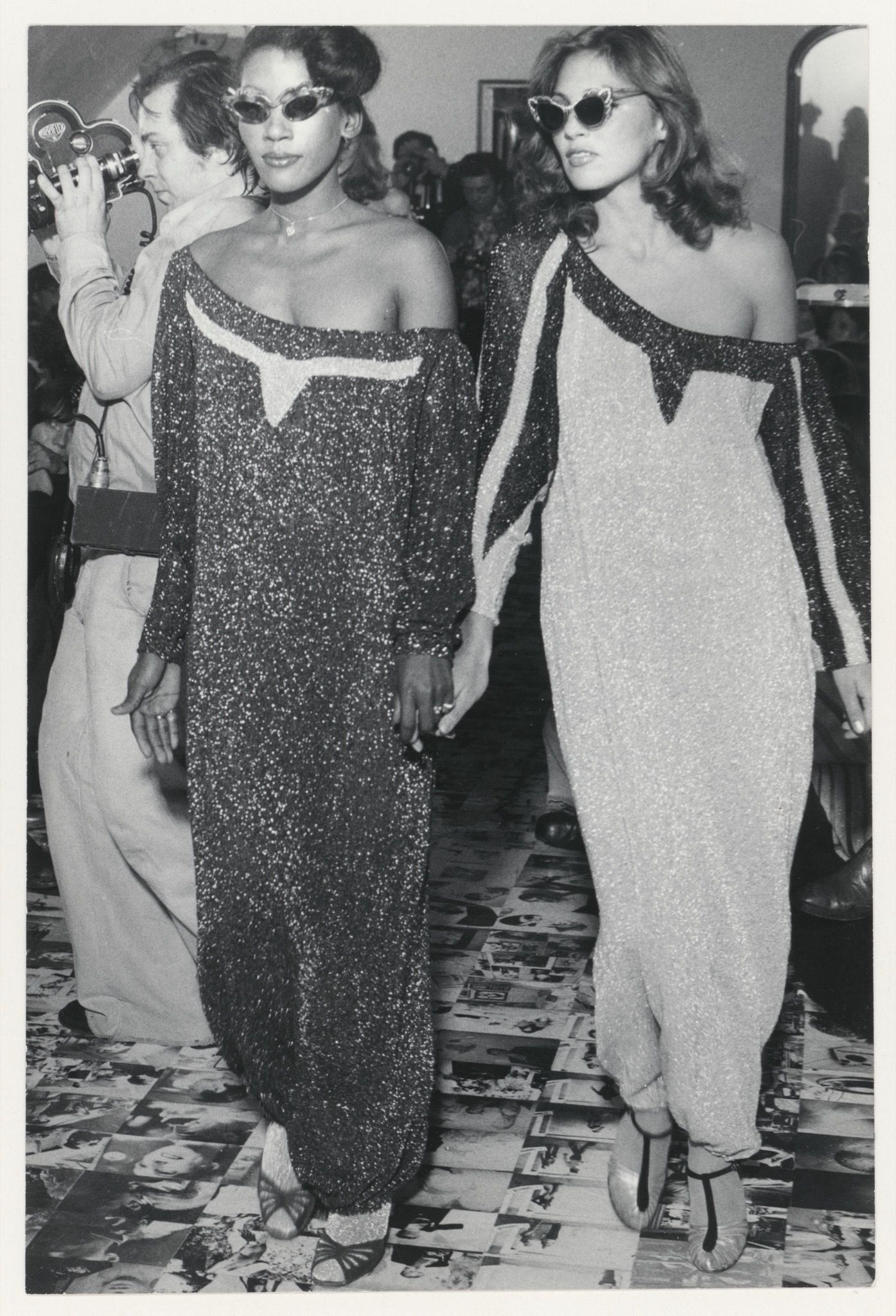

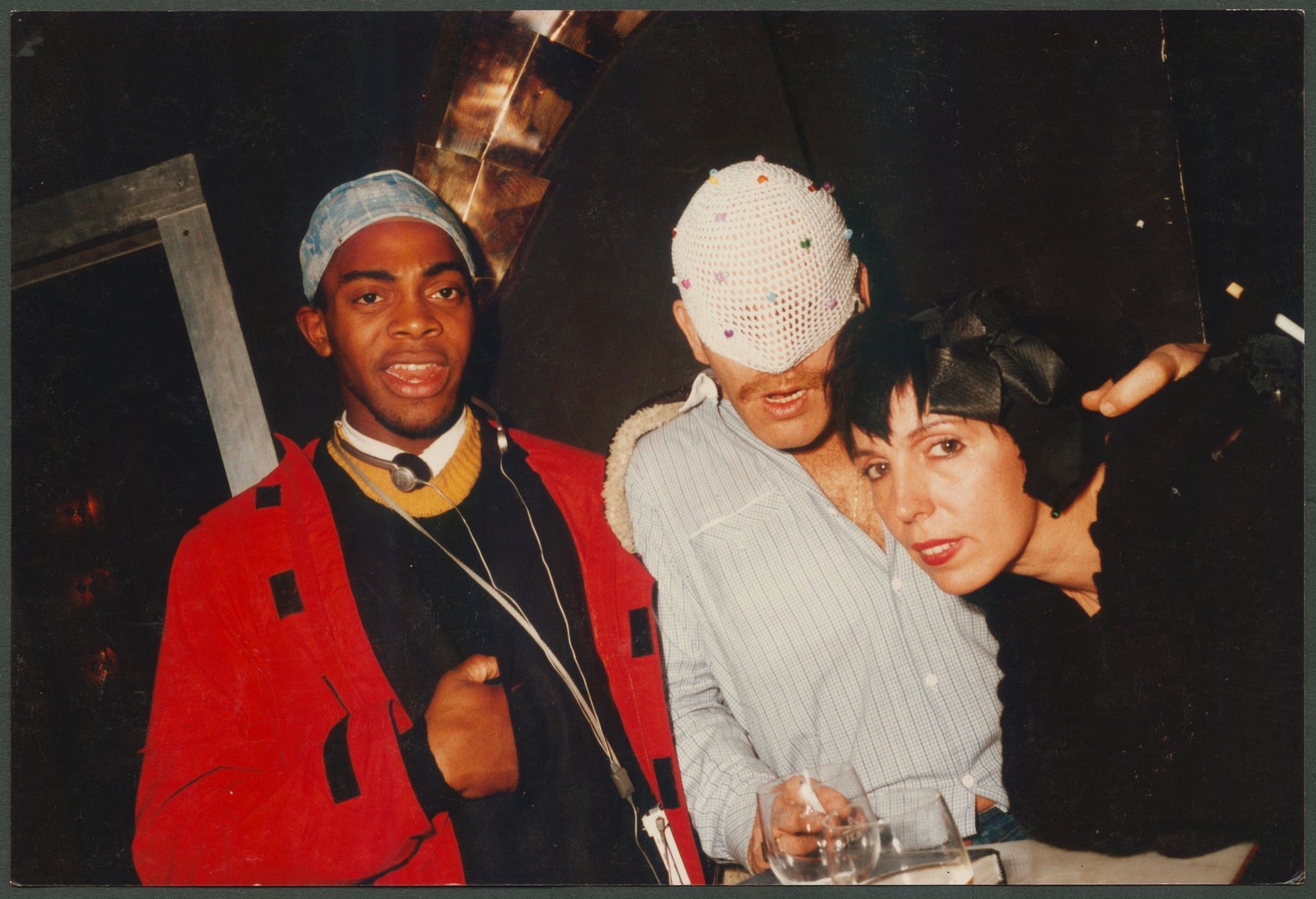

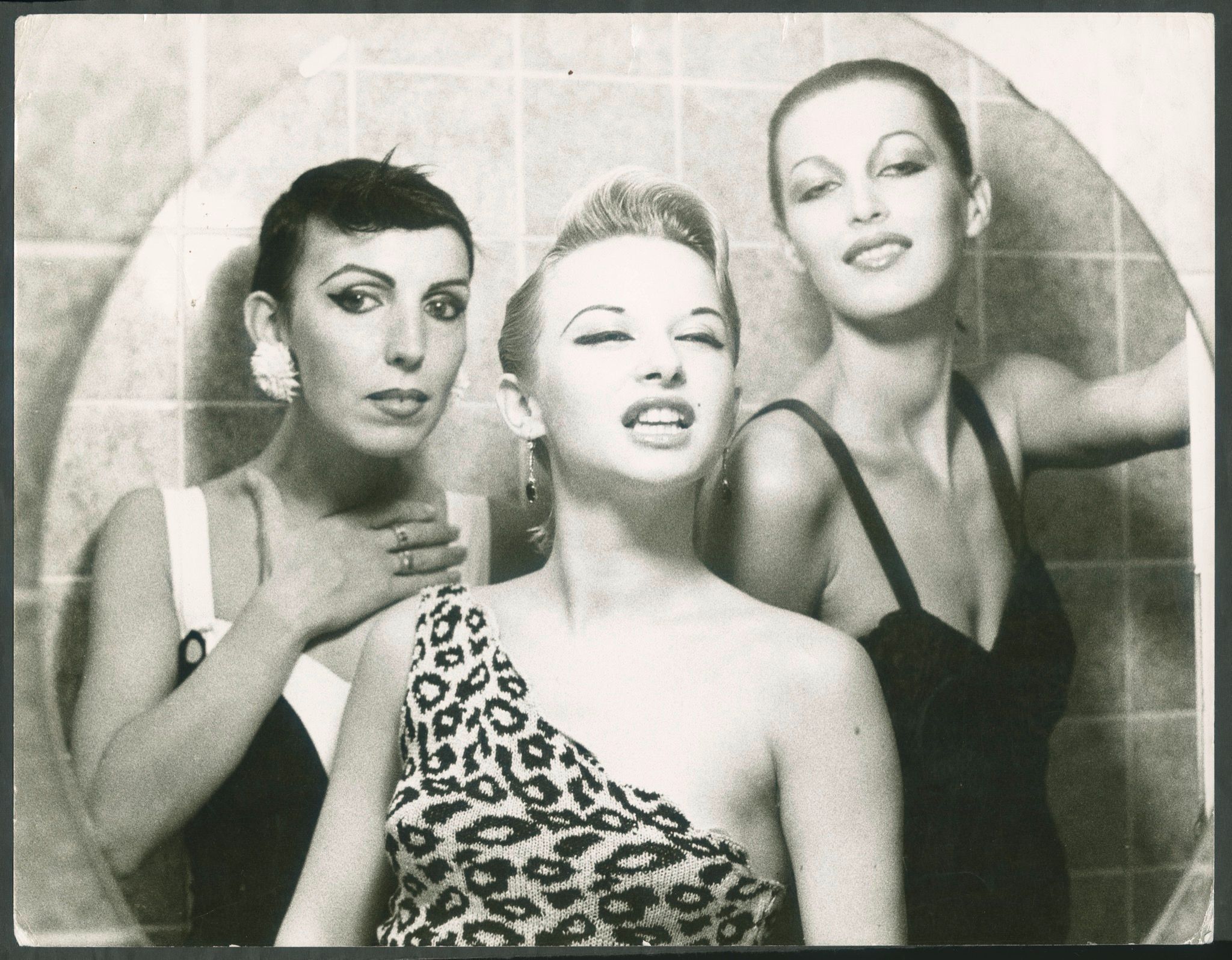

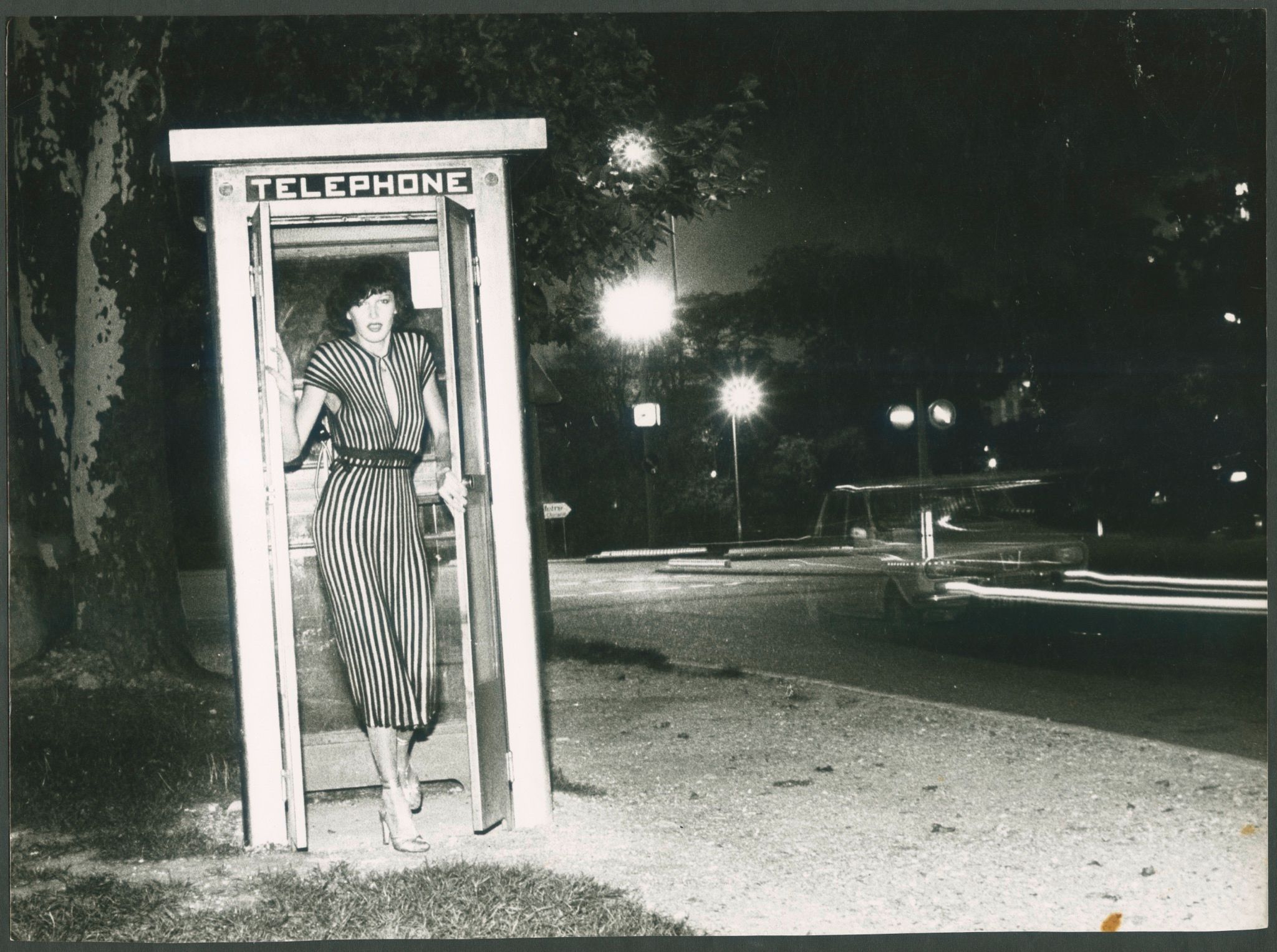

IF YOU DIDN’T KNOW, NOW YOU KNOW: BERLIN INCUBATED FASHION’S UNSUNG KNITWEAR HERO. SHE IS THE MISSONI OF MOTZSTRASSE, THE TALITHA GETTY OF TIERGARTEN – A POST-PUNK LUREX LUMINARY WHO GAVE MARC NEWSON HIS BERLIN BREAK, MARTIN KIPPENBERGER THE BENEFIT OF THE DOUBT, AND KRAFTWERK A RUN FOR THEIR MONEY. NOW, FINALLY, CLAUDIA SKODA TELLS HER STORY.

“Modern since 1973”: it’s a battle cry as simple as it is witty. Forty-six years after she went into business as a fashion designer, Claudia Skoda is an agile and deadpan 70-something, proud of her digital hearing aid, unapologetic about her spliff smoking, and still notorious for her groundbreaking knitwear — the medium that made her famous.

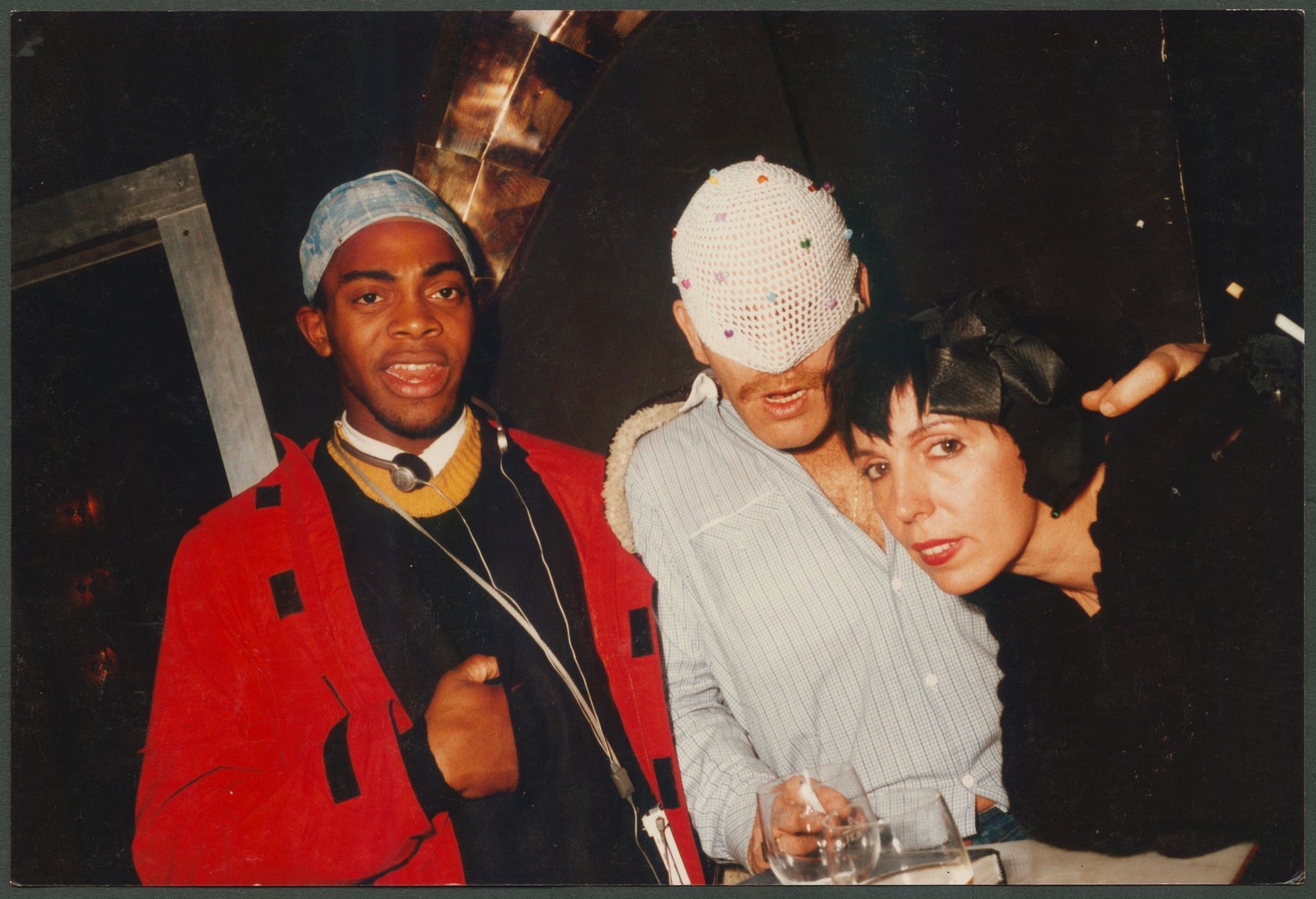

Skoda has been a Berlin fixture since the 1970s, when she fled a life of convention and moved into a disused factory. One of the first inhabited lofts in the still divided city, the now legendary space became a home, work atelier, and crash pad for a roster of generation-defining artists, musicians, and designers. Skoda’s was the gritty, crazy, self-absorbed Berlin that everybody still loves to remember, dwelling in the city’s fading past as half-assed gentrifiers encroach. Art was and remains an adventure — never a business — in Skoda’s Berlin, where boundaries have always been generously ignored, despite the literal barriers imposed for so many years. While the Wall was up, the designer partied with David Bowie and lived with Martin Kippenberger, who created a legendary “photo runway” for her studio. Once, Kraftwerk wrote a couple of chords down for her to play with, and her band, Die Dominas, turned them into an off-the-cuff proto-techno hit. In the early 1980s she conquered New York, opening up shop in SoHo, right across from Vivienne Westwood. But she remained a true Berliner at heart, returning to her hometown on the brink of reunification and awash with European promise (and, possibly, capital). In 1992, she commissioned a young Marc Newson to design her first German store — one of the future design star’s first interiors, and Skoda’s retail debut on Ku’damm, Berlin’s answer to the Champs-Elysées.

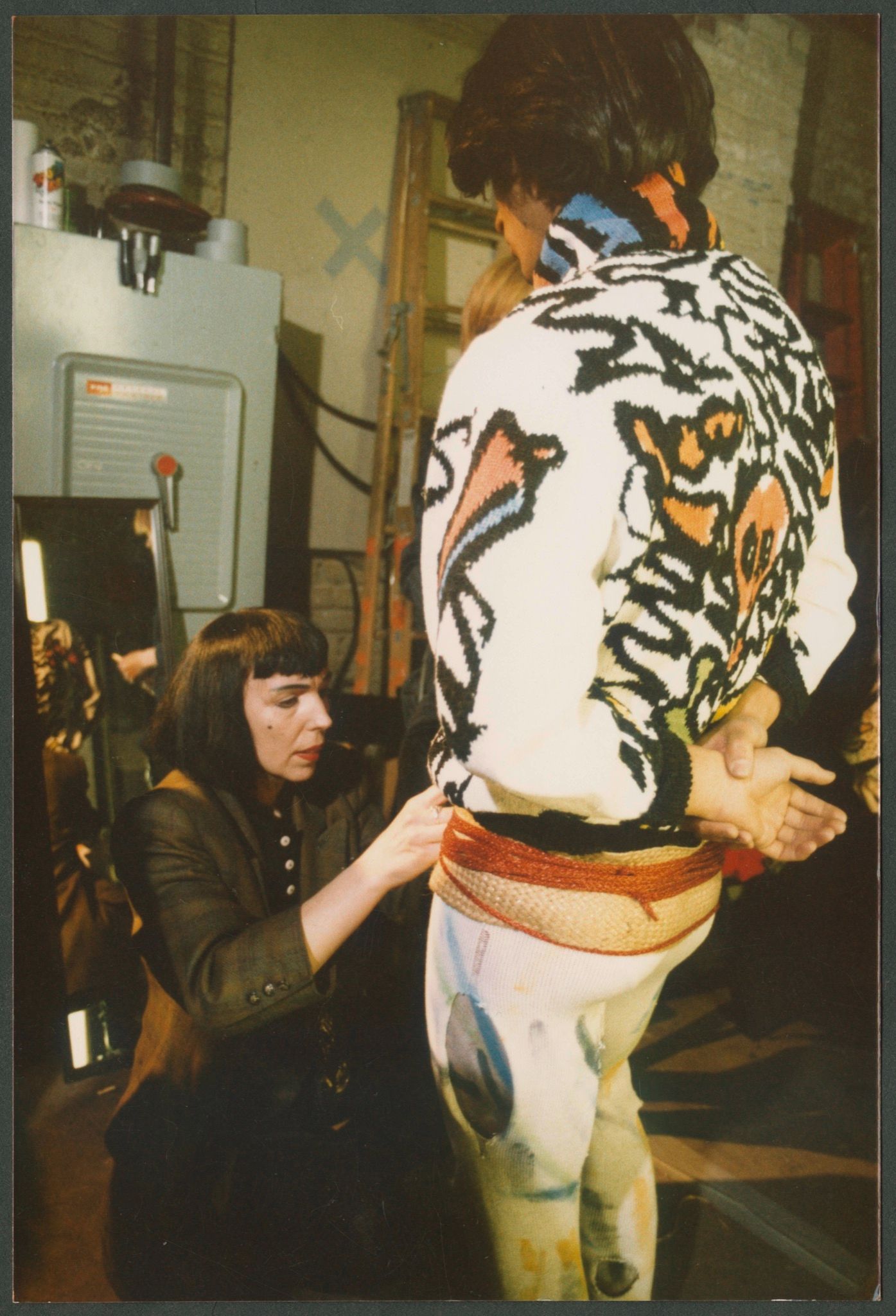

Skoda now works out of a studio in Berlin-Mitte, experimenting with cushion sculptures and tie- dyeing knitwear. She’s preparing her next museum show, set to open in late 2020 at Berlin’s Kultur- forum, located between the old masters of the Gemaldegalerie and Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie, perennially under renovation. But Berlin history isn’t the only thing wetalked about when I visited her at work — we also covered models on heroin, Kippenberger in Ibiza, and a piss-flooded fetish club in the Meatpacking District (before the High Line and Standard Hotel, of course).

ON GROWING UP IN POSTWAR WEST BERLIN:

I was born in Wenckebach hospital, Schmargendorf, during the war — I had an emergency baptism — and raised in Steglitz and Lichterfelde. My father ran a tailoring shop on Schlossstrasse that made suits and coats for men. His tailors came all the way from East Berlin, with their sandwiches wrapped in newspaper. My father’s girlfriend made dresses for women, and as a little girl I would sit among the mountains of tulle and sequins. Nearby was the Titania-Palast movie theater. I once witnessed Marlene Dietrich getting out of her limousine there.

ON THE ORPHANAGE:

When I was 10 my father put me in an orphanage, and I lived there on and off until I was 18. It was mostly my stepmother’s doing — she would sew me the most beautiful dresses and then cut them into pieces in front of my eyes when she was mad with me. When they had fights my father had to prove something: I was beaten, then I would be daddy’s girl again. The orphanage was so unpleasant — I can’t even think about it. The Protestant teachers there robbed me of any illusions. They thought I was a bad girl, rebellious and difficult. But I didn’t have sex until I was 18. I married my first boyfriend.

ON HER FIRST (AND LAST) OFFICE JOB:

I got an apprenticeship at the Tagesspiegel (1) and eventually became an editor. I basically read all day, and at night I would go to jazz clubs: Riverboat, Eierschale, Quartier Latin, Old Eden Saloon. They were full of students with Julius Caesar haircuts, nickel glasses, army coats, jeans — nihilists, basically. Some years later, some friends and I drove to a concert in the countryside in a Volkswagen bus. Alexis Korner was performing — he was famous for discovering the Rolling Stones. When I got back to Berlin on Monday, I called in sick and never went back to work. My punishment for quitting is that I’m still dreaming about my assignments. Sometimes it’s like I’m still working on them in my sleep.

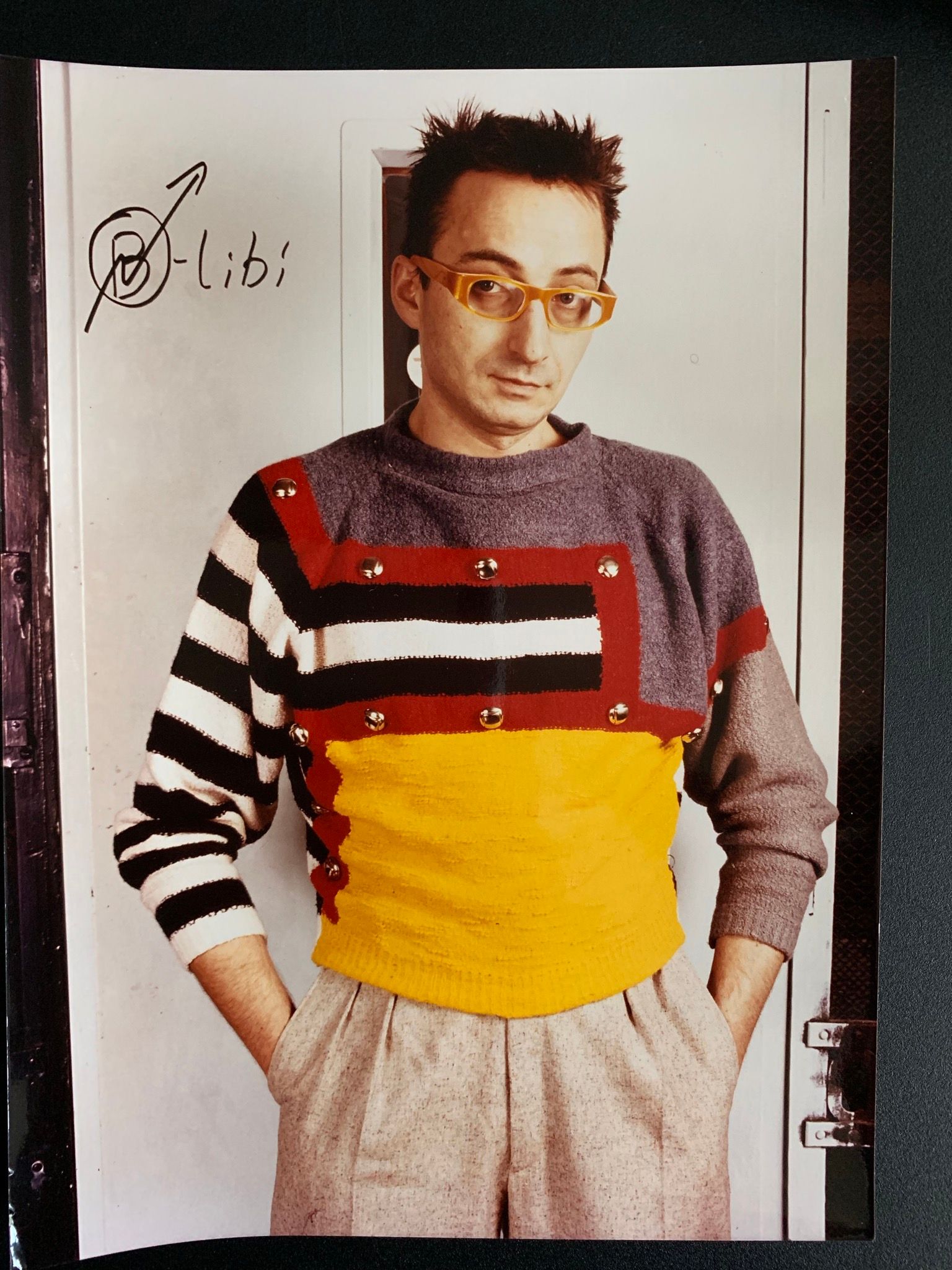

ON COMING TO KNITWEAR:

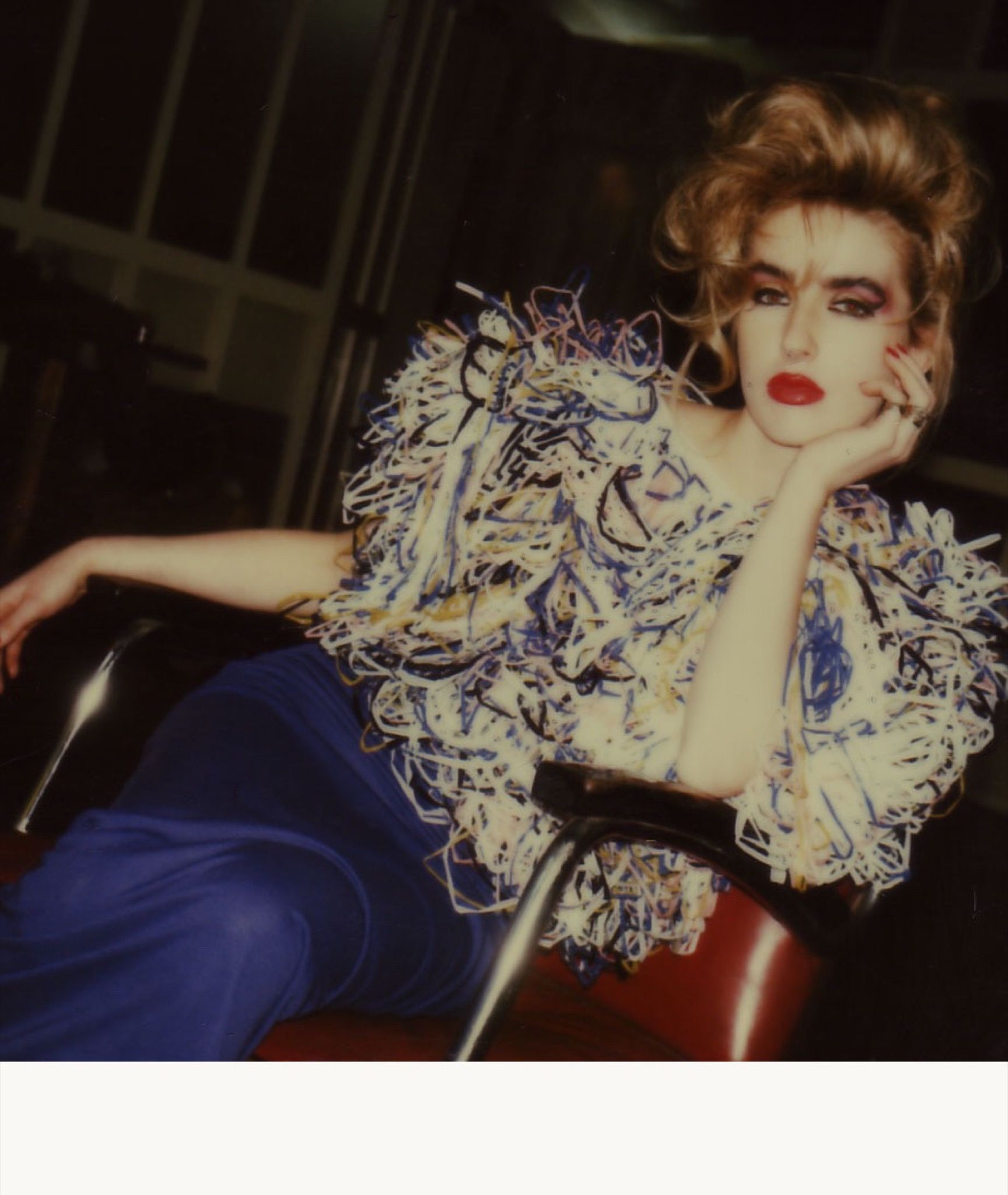

In the late 1960s the only place to shop for clothes in West Berlin was C&A, (2) so to find something extravagant or extraordinary we had to travel to Amsterdam or London. I had been knitting a bit for some boutiques — sewing felt too close to my father. I wanted a pair of knitted pants, so I bought a knitting machine. The actors from Theaterforum, which put on Peter Handke (3) plays, started ordering my stuff. [André] Courréges was hot at that time, and I was making white pleated bell bottom pants that came with a matching zipper jacket, like the ones the mods were wearing. All the wool shops in town only really catered to grannies, but one day we found a supply of thin yarn in all colors. We used it for dresses and mixed it with Lurex. People were crazy about it. A knitting machine had nothing to do with our grandparents’ world. Our style icon was Talitha Getty: hippie de luxe. And we did not overintellectualize. We wanted to look sharp and go out and party. At some point, years later, all the DJs in Berlin were wearing my knit pants. They were comfortable and special.

“We tried a new way of living together, but it was by no means the scruffy commune life that people might think of. … There was only chaos when it came to doing the dishes.”

ON LOFT LIVING (BEFORE LOFTS WERE A THING):

I would smoke joints and drop acid once in a while, but the wild times had yet to come. The first loft I lived in was on Reichpietsch/ufer, next to the vast apartment where Ton Steine Scherben (4) lived. On weekends the steam heating was turned off. It was freezing. In 1972 we moved to Zossener Strasse, into what we called Fabrikneu, and I ended up living there for almost 25 years. “We” at the time was me, my husband Jürgen, Jenny Capitain, the drummer Klaus Krüger — who later toured with Iggy Pop — the painter Angelik Riemer, and the Super 8 filmmaker Reinhard Bock. We tried a new way of living together, but it was by no means the scruffy commune life that people might think of. We would drive to KaDeWe, (5) buy groceries, and cook together. There was only chaos when it came to doing the dishes. Once I invited the New York fashion designer Andre Walker to Berliner Modewoche [Berlin Fashion Week], and he stayed with us. His girlfriend brought all these Barbie dolls with her and erected a huge house for them. Andre was taking part in a collection show I called “Veitstanz.” (6) We all had these old toy weapons, like clubs and morning stars, and would playfully dance and fight around the house.

ON THE COTE D’AZUR:

We just got on the bus and headed south. We went to Cannes and just opened our suitcase in front of a high-end boutique. The shop assistants came swarming out of the store to try on our clothes.

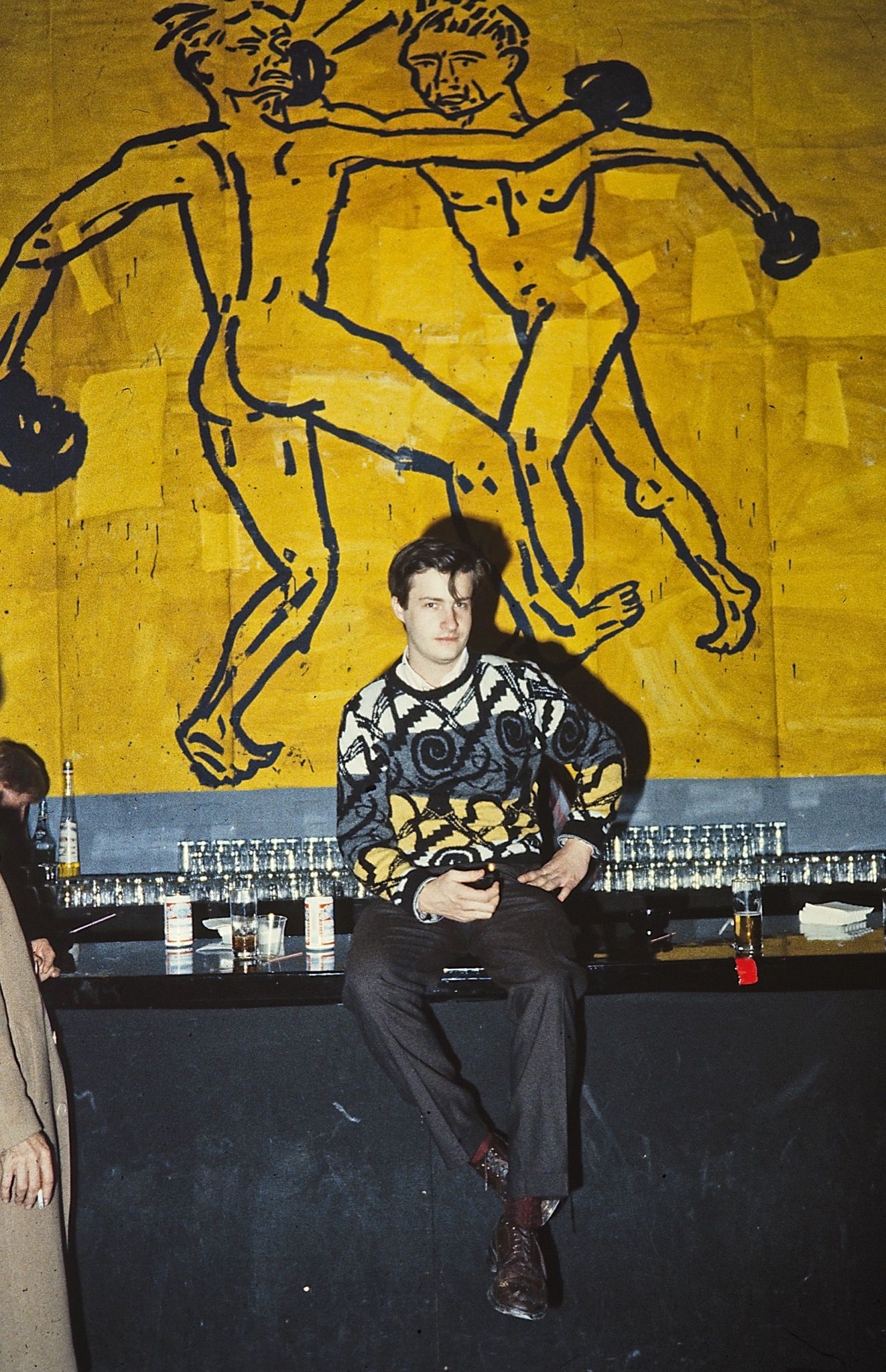

ON MARTIN KIPPENBERGER:

Our plan for Saint-Tropez was to sashay around at the harbor in high heels and colorful dresses in front of all the yachts. But nobody bought anything there. We continued on from Saint-Tropez to Ibiza, where we wanted to do a fashion show. But we met Martin Kippenberger instead. He didn’t go to the beach; he would just drink and smoke, and throw his drawings into the ocean and take photos of his own body. We invited him to come live with us in Berlin. One week, he took thousands of photos of us — of our family, you could say — printed them, photocopied them, and arranged them on our floor. My husband sealed it so you could walk on it, and I showed my clothes on it. We kept our photo runway visible for years before covering it up. When gallerists Annette Kicken and Gisela Capitain, the sister of my good friend Jenny, came by to retrieve it, there were only fragments left. They had it for 10 years before anyone bought it. Now it’s behind safety glass in the art collection of a billionaire.

“Officially, they were in Berlin to get off the drugs, but Iggy would always raid our medicine cabinet and eat everything, even the birth control pills.”

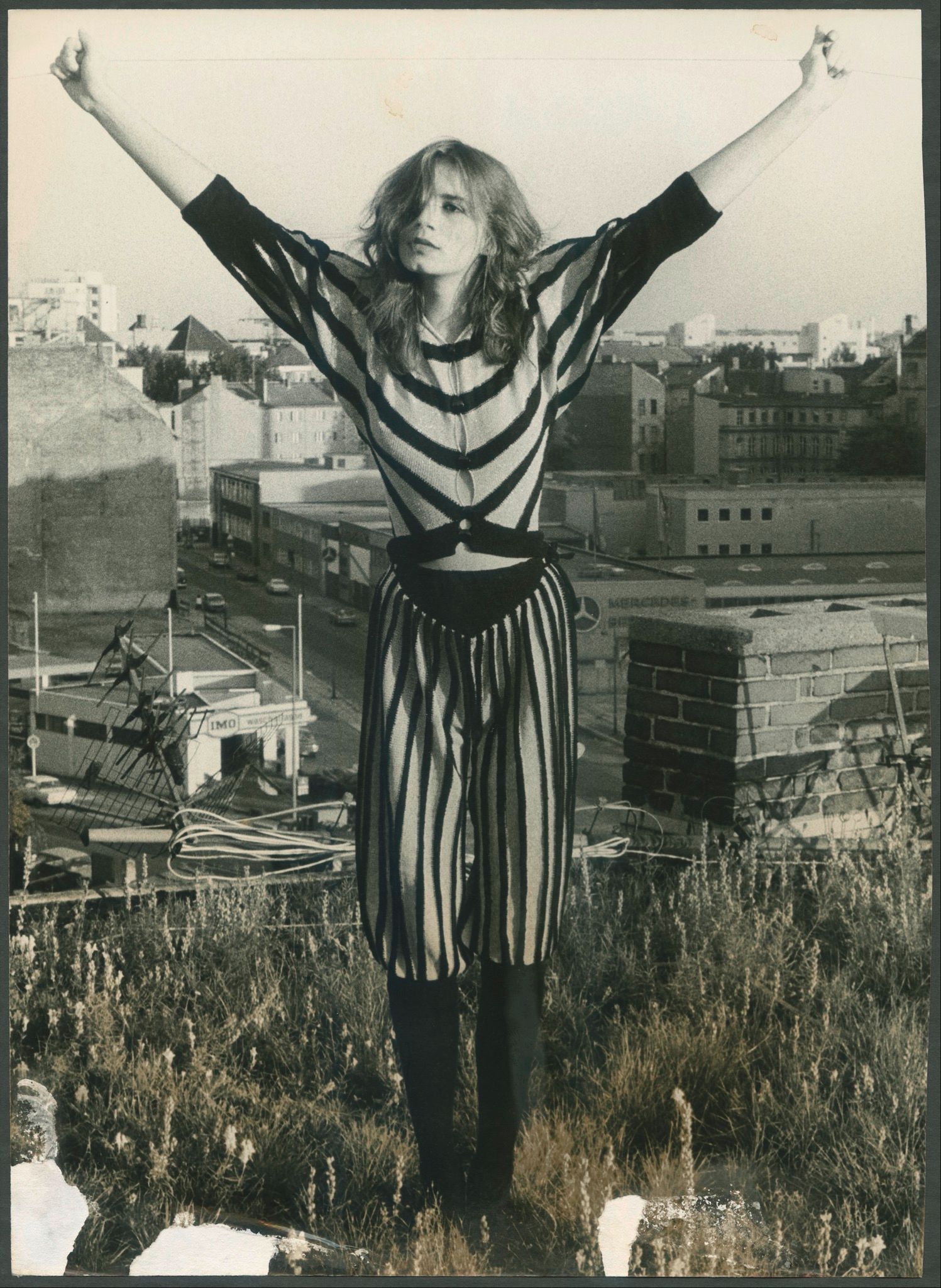

ON THE RAGE:

I officially started my business in 1973. Soon the press was crazy for us. In the 70s I made transparent, colorful, sexy, glamorous dresses. They were so thin that what they were made of was almost invisible. Was it even knit- wear? We were sold in more than 50 stores. We did the fairs — how I hated them! They always wanted glitter. I wanted punk, and my clothes became all the rage. For one presentation we installed a big tent and projected Die Dominas music videos — all the other brands wanted a booth next to ours. Kraftwerk was standing at the bar, and I was wearing a rubber skirt and roller blades.

ON HER KRAFTWERK-INSPIRED, DOMINATRIX-THEMED 10-INCH:

The guys from Kraftwerk were heavily into dommes. When they gave me and my friend Rosi Miller a piece of paper with chords on it — a dominant seventh and a subdominant — we just put on the synthesizer and started fooling around. We did not even know that Rosi’s then boyfriend, Manuel Gottsching, (7) was recording us. “Die Wespendomina’” (1981) became a cult hit with DJs. Some people claim the song was techno before techno, and the 10 inch is very expensive today. Back then, everyone around us was making records. I even founded a label. Our single was stolen from us and re-recorded, and it became a massive club hit in the United States. At some point we thought about re-releasing the original, but it was too complicated. The whole story was thrilling, annoying, and adventurous.

ON CELEBRITY:

In the video for “Ashes to Ashes,” (8) David Bowie wears a pair of black studded pants I made back then. Bowie would buy his outfits at a workwear store called John Glet. He wore a beard at the time; he did not look like a pop star at all — not like Iggy Pop, with his huge puppy eyes. But neither of them behaved like a star. They were recording at Hansa Studios, not far from Fabrikneu, and would storm into our kitchen to check out what was in the fridge. Officially, they were in Berlin to get off the drugs, but Iggy would always raid our medicine cabinet and eat everything, even the birth control pills. We listened to the rough cut of “Idiot” a lot. David’s the one who told me, “You have to go to New York.” So I did.

ON THE UP AND UP IN MANHATTAN:

When I showed Bergdorf Goodman my designs, they picked one very intricate piece and said, “We’ll take 200.” Nothing else. There was no way we could have produced them in that quantity. So I needed my own store. We found one on Spring and Thomp- son: shiny concrete, with orange and silver containers for the products, and a facade made of steel beams and glass. I was proud of that idea — steel and glass are cheap in New York. Plus, it was burglarproof. I fainted a couple of times when I first got there — I had terrible bladder pain and had to go to the emergency room. They sent me to a shrink. I was suffering from anxiety, something that I never experienced in Berlin. Then I met Skippy. We were a couple for 21 years. He had a loft on 10th Street. Above it was a piss club with a rubber room that leaked. Sometimes we had a stream of piss coming into our loft. The West Side was different back then — you had hookers and gay clubs, and some cab drivers would not drive you there. But I lost my fears. I felt safe.

ON THE VERGE:

“If you mess up, my head is on the chopping block,” I was told by Volker Hassemer, a senator in Berlin’s Department of Cultural Affairs, when the city was named European Capital of Culture in 1988. I had been tapped to somehow spend a 1.5 million Deutschmark budget on a project, so I asked architect Hans Kollhoff (9) to design a 70-meter free-hanging catwalk in Hamburger Bahnhof. We invited seven fashion designers from all over Europe, among them Vivienne Westwood and Marc Audibet, and created a retrospective of work by the Austrian designer Rudi Gernreich. Everything was cool until the designers brought their models: Westwood came with Sara Stockbridge, who was always getting naked, and others were on heroin. The dancer Michael Clark, who was at the height of his fame then, was not any better behaved. I had to make sure that the famous monokini from Gernreich’s archive didn’t get stolen, so we had a wardrobe person on duty just to guard that moth-eaten panty. Our choreographer, who we’d flown in from New York, became so sick — with complications from HIV — that he couldn’t work, and we had to find someone else. In the end, we pulled it off. The reviews were devastating. After the Wall came down, I would have liked to keep producing big events like the one at Hamburger Bahnhof. But in the end there was no money. I could not compete with the big brands like Hugo Boss that started coming to Berlin.

ON MARC NEWSON AND WINDOW SHOPPING:

Eventually I did open a store on Ku’damm. (10) I wanted to make a statement, and I asked Mare Newson to design it. We moved into a former travel agency with a strong 1970s design: a tube-shaped space with rounded windows. That was very fashionable back then, and Marc liked it. His star was rising rapidly, so we had tons of design and architecture students visiting. I would have loved to have Marc’s “Madonna” couch, (11) but unfortunately it was never mine. The floor and the counter were made of aluminum, which worked nicely —except in summer, when the floor would get crazy hot. Whenever we would put our aprons in the window, men would come by and stare. They looked like silver chain armor. The apron is a totally over-looked item. It has sex appeal.

ON THE INDUSTRY:

In the end, I detest fashion that understands itself as art. I want to create something I can wear, something I want to wear. Avoiding the mainstream has always been my driving force. Vetements, in my eyes, is lacking substance. Too much hype. Once I was a hype too, but I prefer to be a small hype. That way I am not forced to do things I don’t feel like doing. My luxury is not money, but freedom. I had a Mercedes once so I could drive around with my Airedale terrier. But I gave it away — the car, not the dog.

“They always wanted glitter. I wanted punk.”

Notes

1) Tagesspiegel is one of Berlin’s still existing but heavily struggling daily newspapers.

2) C&A is a downmarket department store. The logo back then was a Palomino pony.

3) Peter Handke is an Austrain writer and poet. His play Publikumsbeschimpfung (Offending the Audience) made him a star. He was awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in Literature.

4) Ton Steine Scherben was a legendary German band deeply rooted in Berlin’s left-wing youth culture. Its anthem was “Macht kaputt, was Euch kaputt macht” (Destroy what destroys you).

5) KaDeWe is a fancy department store — particularly by Berlin standards — with a legendary food hall on the top floor. According to Wikipedia, it is Europe’s biggest after Harrods – making KaDeWe number one if you factor in Brexit. It is currently being renovated by Rem Koolhaas.

6) Veitstanz is an old word for a hypnotic dance.

7) Manuel Géttsching is a musician and composer, and one of the pioneers of electronic music. The Guardian once called him “The Göttfather.”

8) The video for “Ashes to Ashes” from 1980 is one of the earliest and finest examples of real storytelling in a music video. It is also from the phase in which Bowie turned from critically acclaimed cult star to major pop star.

9) Hans Kollhoff is an influential and controversial German architect. His intellectual historicism is considered aggressively conservative by critics.

10) Ku’damm is the abbreviation of Kurfürstendamm, a big boulevard in west Berlin where most of the luxury retailers are located.

11) Madonna used Marc Newson’s iconic Lockheed couch in her video for “Rain,” by director Mark Romanek. One of the couches was sold at auction for 2.4 million pounds. It’s officially the most expensive piece of contemporary furniture.

Credits

- Text: Adriano Sack

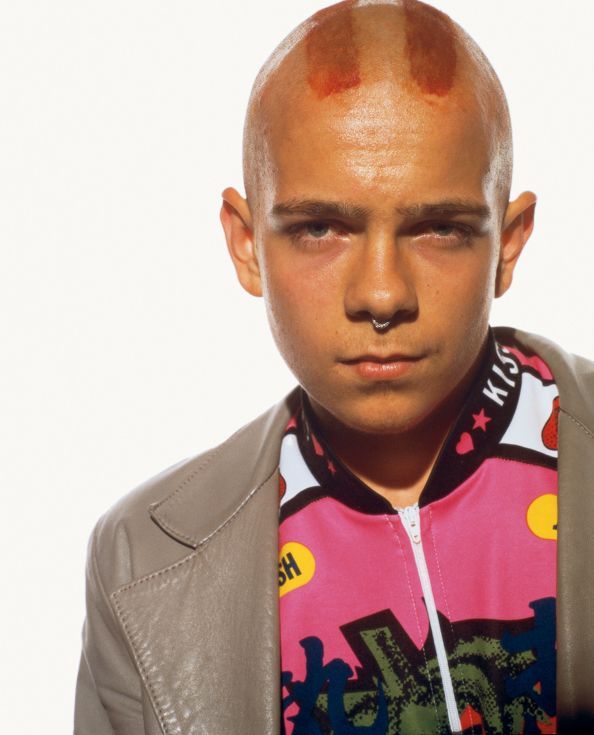

- Portrait: Vitali Gelwich

- Archival Photographs: Courtesy of Claudia Skoda