The Club Culture Paradox: Aaron Altaras, Freddy K and Rave On

|Cassidy George

The premiere of the film Rave On (2025) at RSO began like any other night at the club. Crowds in black tracksuits and utilitarian, fitness-adjacent uniforms drifted toward the venue’s open-air “valley.” People queued, verifying guest list spots or arguing about not being on them. Bouncers were unamused and unenthused. Outside, friends hugged friends and party acquaintances, while others tucked tiny plastic bags into their socks around the corner.

Inside, the DJ booth and dance floor had been replaced by a stage with a massive screen. The people seated on benches in the front were like a Berlin Club Culture edition of the board game Guess Who? On an elevated platform, Sven Marquardt sat front and center in a director’s chair while Westbam weaved across the stage in search of the bathroom. Artists who appear in the film—Lucia Lu and DJ Hyperdrive—mingled with many others in attendance who were there to show support, such as Brutalismus 3000 and Ski Aggu. Just before the screening began, one of Berlin’s most universally beloved DJs, Freddy K [Alessio Armeni], gave a brief intro speech. Rave On’s lead actors Aaron Altaras and Clemens Schick drifted toward the bar behind the benches, perhaps so that no one would watch them while they only partially watched their film.

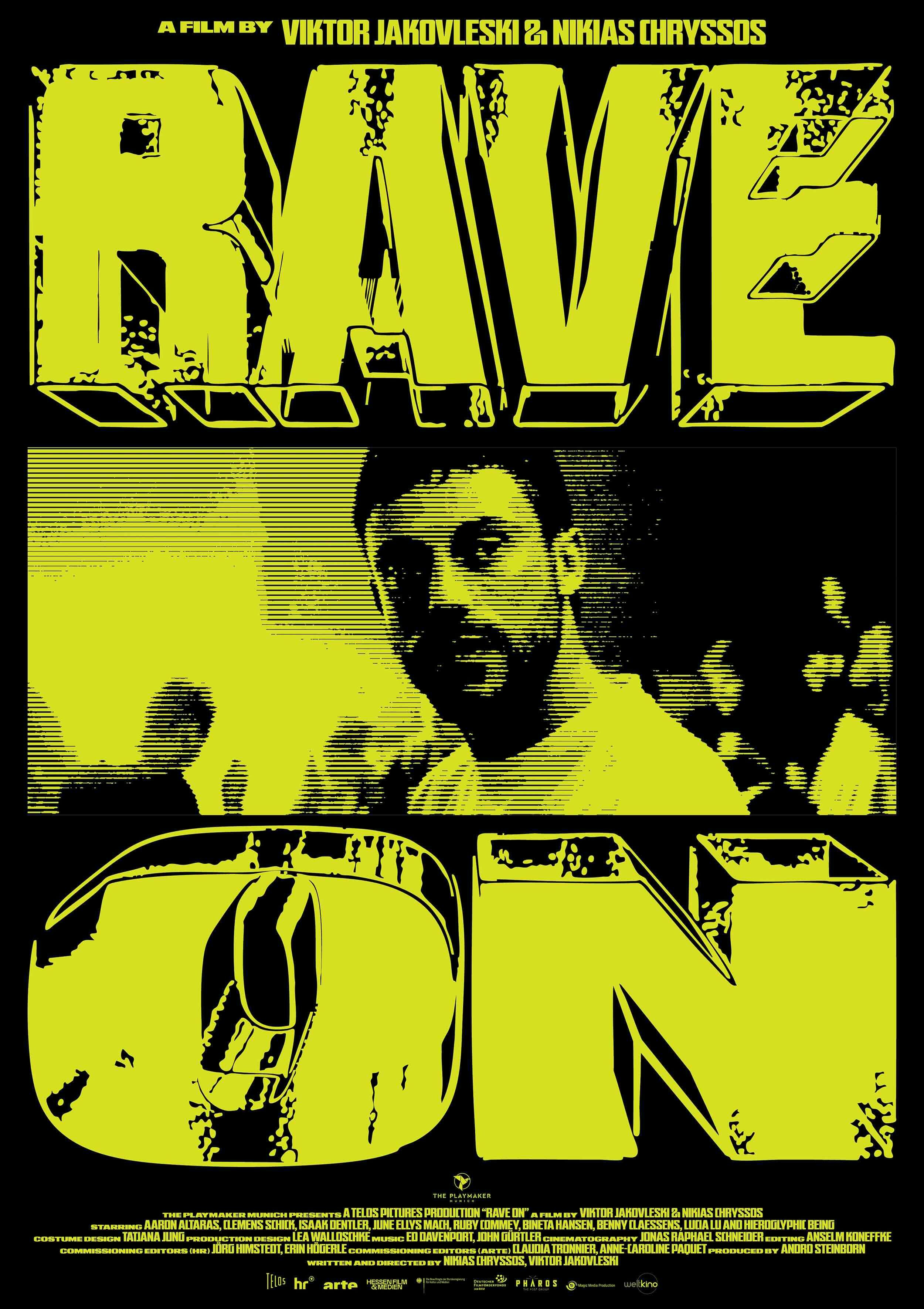

Written and directed by Viktor Jakovleski and Nikias Chryssos, Rave On riffs on The Odyssey, one of storytelling’s oldest templates. Its protagonist Kosmo (played by Altaras) enters a club with a singular mission: giving his new vinyl record to the evening’s headlining DJ Troy Porter (played by Jamal Moss aka Hieroglyphic Being). Within this labyrinthine, fictional venue, Kosmo encounters the full Grecian spread: obstacles, enemies, sirens, side quests, failure, redemption.

With beautiful color grading and a memorable soundtrack created by Ed Davenport, Rave On is a stylish reframing of a narrative trope that also confronts a local paradox. Despite its centrality to the city’s identity, Berlin club culture is rarely tackled head-on or in depth in large-scale storytelling. The cult-classic film Berlin Calling (2008) is now a retro homage to a foregone era, while more recent movies and series such as Victoria (2015) and Beat (2018) make club culture a setting, rather than a focus. This is even true in electronic music journalism, where there is a longstanding shortage of meaningful coverage and content—despite ever-growing interest and demand.

Most people who have found a true home in Berlin’s club culture view it as a sacred anomaly. And an extreme faction within that crowd of people believe that protecting club culture means not talking about it in public media. For decades, the city’s no-photo policy acted as a kind of covenant: the less the scene was documented or monitored, the more it could exist on its own terms — but that protection is eroding. Video is now the most valuable currency in the global DJ economy. The right clip of an epic drop and euphoric crowd can catapult an artist into stardom overnight. The more that nightlife becomes “content,” the more power media gains to influence who gets booked, what’s getting played, what it feels like to go out, and what people think clubbing is about.

Many of the concerns about increasing visibility and the endangerment of precious spaces are valid, but fear and anxiety around this topic contribute to the aforementioned void in quality storytelling. Oftentimes, those who revere this culture the most are the most hesitant to depict it. And yet, the creators of Rave On acted on an impulse that I gather almost all true purveyors of Berlin nightlife have felt at some point or another: to document something rare, ephemeral, and unique before it disappears entirely. Jakovleski and Chryssos are now among the brave few to create an immersive portrait of the scene they know, and did so with diligence and empathy.

After the screening, I spoke with Altaras, Jakovleski and DJ Freddy K—whose label, Key Vinyl, is releasing the Rave On soundtrack on a double vinyl LP—about the delicacies of tackling a slippery topic and the power of blurring fact with fiction.

Aaron Altaras: I think it would be funny to say that we know each other.

Cassidy George: What, like from partying? You want me to explicitly disclose that in the story?

AA: Not necessarily, I just think it would be nice to acknowledge that you know me privately, because interviewing someone you know is a very different task than speaking with a stranger.

CG: When I saw you right before the movie started, you told me you were feeling really nervous. I assumed you were kidding.

AA: I wasn’t lying! Usually, I’m so cold-blooded when it comes to this shit, but so many of my friends are here today. It kind of feels like that awkward moment when it’s your birthday and everyone comes with the candles and the cake. It doesn’t have anything to do with the film, although I’m happy that people who are important to me will see it. Sharing the things you care about with the people who matter to you gives those things more value. Keeping things to yourself gives them less value. If they love or hate this film––fair enough, that’s fine with me. I also think that failure can be very liberating.

CG: In the film you play a DJ and producer, but you also used to DJ and produce with your brother as Alcatraz. Now your brother Lenny is a solo act. Why did you stop?

AA: You need both hands to do something well, and when you want to do two things at the same time… in my case, I just ended up sucking at both. I disappointed myself and I was in a place where I wasn’t enjoying music or acting. I felt like I was deceiving myself and others, all while operating under an umbrella of “success.” At the end of the day, I didn’t like going to work. This issue was the root of many other things that happened afterwards, and even caused a semi-public meltdown in my friend group.

I like DJing because I like music, and I like music because I like my brother. The project was always about sharing something with him. He has his own light and I would never want to stand in the way of what he is pursuing. He compulsively needs to make music, the same way that I compulsively need to [act]. Now we are closer than ever. I actually think my relationship with my brother is the thing I am most proud of in my life.

CG: Why do you think it’s often difficult or uncomfortable to watch things about club culture? I think for some of the people closest to it, there’s an impulse to wince, cringe, or just look away entirely.

AA: Well, first of all: we aren’t everybody. I think it’s hard for us to watch because it’s too close to home. You see something that you know, but not necessarily as you know it. That causes dissonance, and the dissonance makes it difficult to process. This is an artificial project, of course—it’s not me—but even still, you can’t imagine how often we thought about the tote bag I’m carrying in the film. They kept saying, “Please Aaron, just hold it like a normal tote bag,” and I was like, “Yeah, but I can’t hold the tote bag like Aaron.” Obviously, as an actor, this is my job—but it gives you a sense of the difficulty of it.

CG: Your biggest roles in the past have been in projects that explore the Jewish experience in Germany, both today and historically. Was it refreshing to be cast in a project that didn’t hinge on this?

AA: Yeah, I think I was typecast for a long time.

CG: In almost all of your past interviews, you’ve been confronted with deeply sensitive and traumatic topics and are inevitably forced to make big statements about war and genocide. It must be a relief to talk about clubbing instead, even though there’s no shortage of impassioned opinions about this topic either.

AA: I do think it’s unfair that’s always asked of me, but I end up saying the exact same things every time because I know what I believe and where I stand on things. It’s funny, the other day I had a little crash-out during an interview. The first question they asked was: “How does it feel to be in a rave film?” My answer to the last question was: “I don’t think the German state should be funding this when there are children dying, but at the same time it is important to protect this culture.” When I read over it, I had to laugh at myself so much. How did I even manage to get from there to there?

CG: Alessio [Freddy K] gave a speech before the film. Viktor, can you explain how and why you got him involved?

Viktor Jakovleski: First of all, I am a raver and a huge admirer of Alessio—I don’t even know how many closings of his I’ve done. When we finished the film and were considering what to do with the soundtrack, we knew it deserved a proper home. Alessio’s label Key Vinyl was our number one goal. A mutual friend introduced us. I shared the plot of the film and told him Ed Davenport was responsible for the music. He immediately said, “I’m in.”

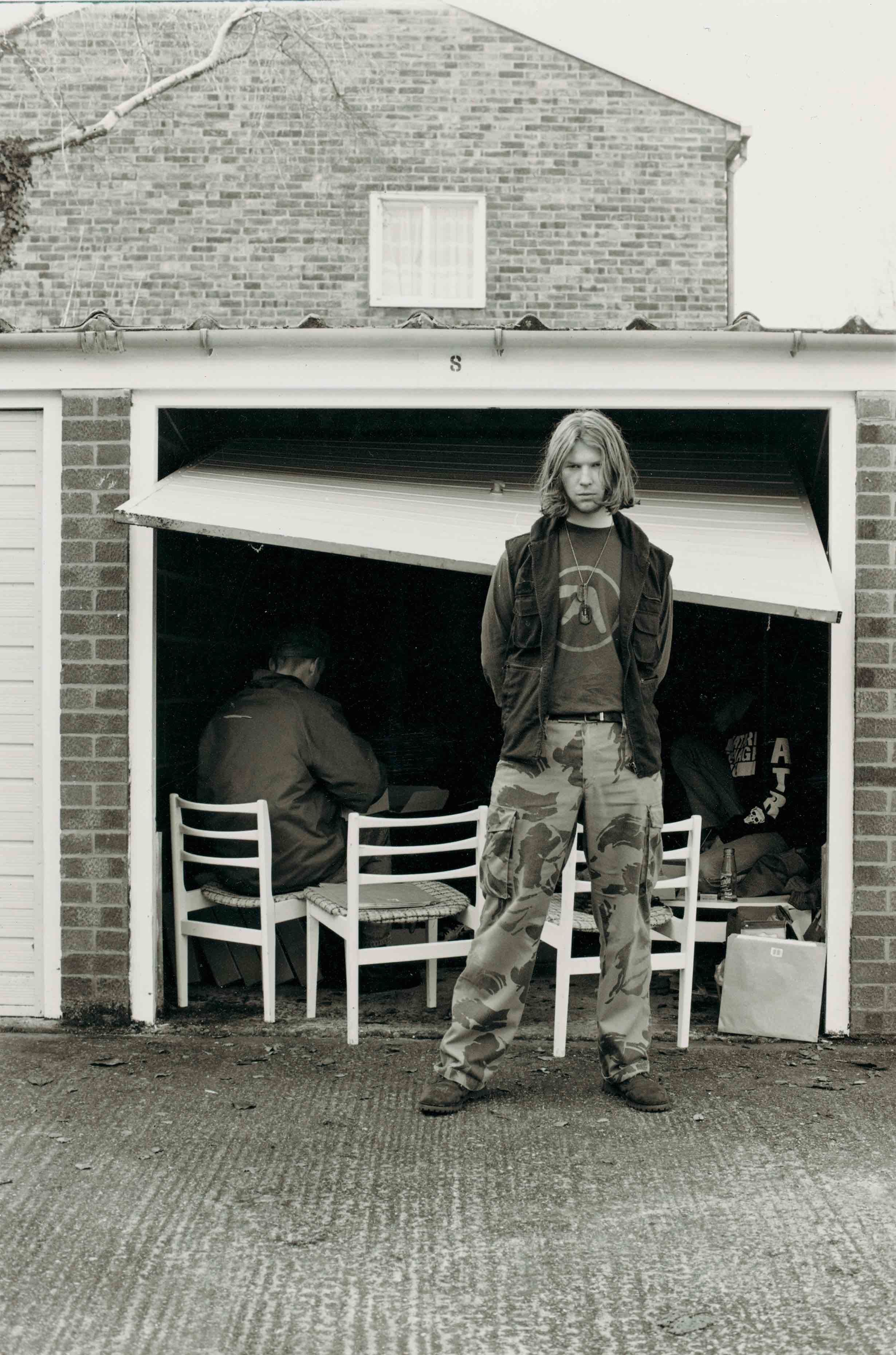

Freddy K: I said that without even watching the movie because I knew Viktor’s work—but also because the character’s story is similar to my own. When I first started going to Berghain, I always brought pressings with me to try to get them to Ben Klock or Marcel Dettmann. I know exactly how it feels to show up at a club with a vinyl in your tote bag to try and approach the DJ and then be shooed away by someone who says, “The DJ doesn’t know you!” Nowadays, I sometimes look over when I finish a set and see five or six vinyls waiting there for me—I think this is such a beautiful way of saying thank you.

CG: I assumed most people just do this digitally nowadays. The plot actually reminded me more of the hustle of mixtape culture in hip-hop, but I think that’s because of where and when I grew up.

VJ: Actually, one film that hugely inspired me was Hustle & Flow (2005). It’s about a guy trying to get his mixtape to Ludacris, and it eventually ends up in the toilet. I thought it was such a great set-up.

CG: I appreciate that the dialogue in the film acknowledges some very big conversations in contemporary club culture—the role of social media, generational divides, musical trends—but touches on them only in passing. It incorporates relevant context without attempting to shape opinions.

VJ: I find it interesting that there is some kind of divide happening in the scene, and I wanted to represent that. There was a lot more of that in the original script, but we wanted to be careful not to overload it with these themes or divert from the core idea. The main character does have opinions about these topics, but that doesn’t mean we agree with them. The lead is very locked up—he’s constantly overthinking and needs to free himself of this. The character of Roxy J represents the opposing opinion, and I think she’s correct in pointing out that we live in different times and that artists have to adapt.

CG: Alessio, how did you react when you first saw the film?

FK: You should know that I get very invested in movies and I believe everything in them. For example, when I saw The Blair Witch Project (1999), I thought it actually happened. I couldn’t sleep for three days! From the second Rave On started, I found it to be very realistic. It also expresses something very specific, this new wave of club culture unique to Berlin. There are only a few other clubs in the world that have this model—such as K41 in Kyiv, Fold in London, and Basement in New York. These are clubs that focus on sexuality and queer inclusivity, with awareness teams and dark rooms. As a touring DJ, I know how rare it is to have these kinds of freedoms. In most clubs, you get kicked out for being on drugs, you can’t go into stalls with other people, and the perception of the kind of people who go clubbing is a negative one.

There were so many moments in the film that felt true to my own life and experience, I almost couldn’t believe it. The film also feels very spontaneous to me, and it manages to avoid all of the stereotypical, cliché mistakes.

VJ: We knew from the beginning that we were not making a film about techno or about any particular club or scene, because if we did, we would inevitably fail. This film is a story about one guy with a record. We tried to keep everything else that happens along the way as authentic as possible. Maintaining this format helped us avoid all of the lurking traps and landmines.

CG: During the screening, everyone laughed during the scene with the Awareness Team member—I think because it felt so realistic.

VJ: I have to give a ton of credit to the club where we filmed. After they agreed to let us shoot there, we rewrote the script according to the place and the people who work there, which includes Lara from the Awareness Team. We originally had the main character waking up on the floor, but Lara helped us rewrite the scene based on how she would comfort someone in that situation. When we asked her to play this role in the film, she was so happy. I think this is what I love most about this project: the way we were able to fuse it with reality. We envisioned a theoretical version of a practical place, added real people into it—and this is what came out.

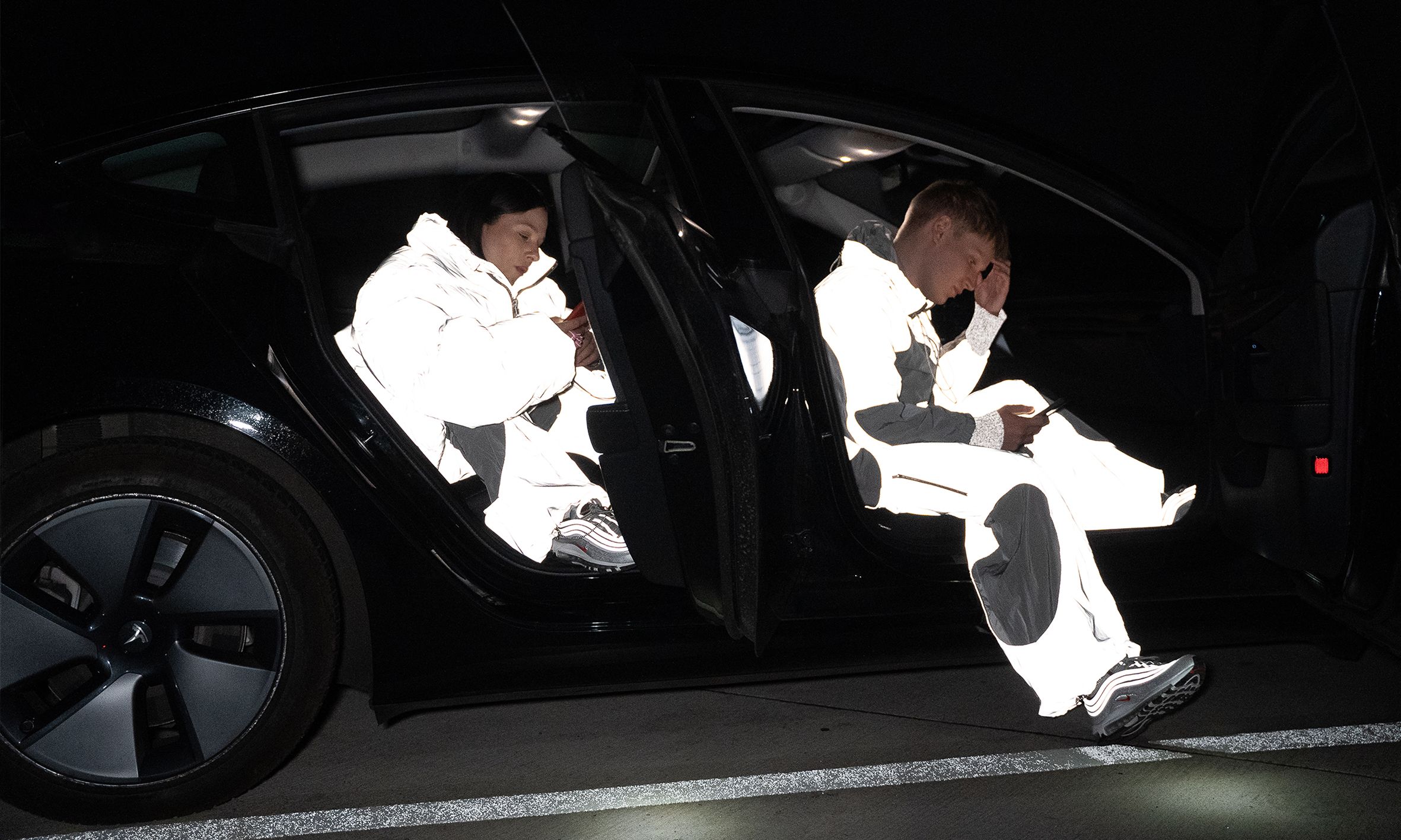

FK: I also loved how the film portrays the social aspect of this scene. Everything is so online now. Concerts and clubs are some of the only places left where you can actually be face to face with other people, have great conversations, and meet people you never would have otherwise.

I actually cried at the end of the film because… You know, I’m 54—I’ve dedicated my life to this. I met all of my friends in clubs. I met my partner in Berghain. I’ve never seen this on screen. Movies like Berlin Calling or Human Traffic (1999) only show one aspect of this culture. There is a lot of darkness and anxiety in Rave On during his trip, but I think the overall message is positive. It shows that there really is a parallel world where people take care of one another.

CG: Were you anxious about how the film would be received?

VJ: This was the most difficult film I’ve ever made, and I struggled with it for many years. I was very nervous. Of course, some people did say, “Why do you feel the need to talk about this and put it on a screen? This is sacred to us.” I told people who felt afraid of this project that I understood their concerns, and that I would probably be afraid if I were in their position as well. Ultimately, I think people were just afraid that we would get it wrong.

The scene is constantly evolving. This project was really just about freezing a moment in time. In 10, 20, or 50 years, people will be able to look back and see what it was like to go to a club in Berlin in 2025. All those videos on Instagram that only focus on the DJ and big drops—these do not represent the climate of club culture either. It’s just ecstasy, and it’s very produced. It isn’t a real or accurate depiction of this world, and that felt like further justification to make this film. I know I’m not showing any emotions right now, but I think—speaking with you and Alessio—I am finally realizing that we, as artists, might have gotten at least some part of it right.

Rave On is now screening in theatres (in Germany).

You can buy the soundtrack from Key Vinyl here.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

Related Content

ABC of AFX

WESTBAM: You Need The Drugs

Brutalismus 3000: “The Secret Ingredient is Controversy”

EDGLRD: Harmony Korine Sets Technology Aflame

Drain Gang

Rave, Relic, Reel: Paranormal Frequencies in Mark Leckey’s Latest Works

Ways of Raving: Geoffrey Mak on Empathy and Psychosis

The rave as mosh pit: BAMBII’s INFINITY CLUB

Thaiboy aka DJ Billybool: Everything “DYR”