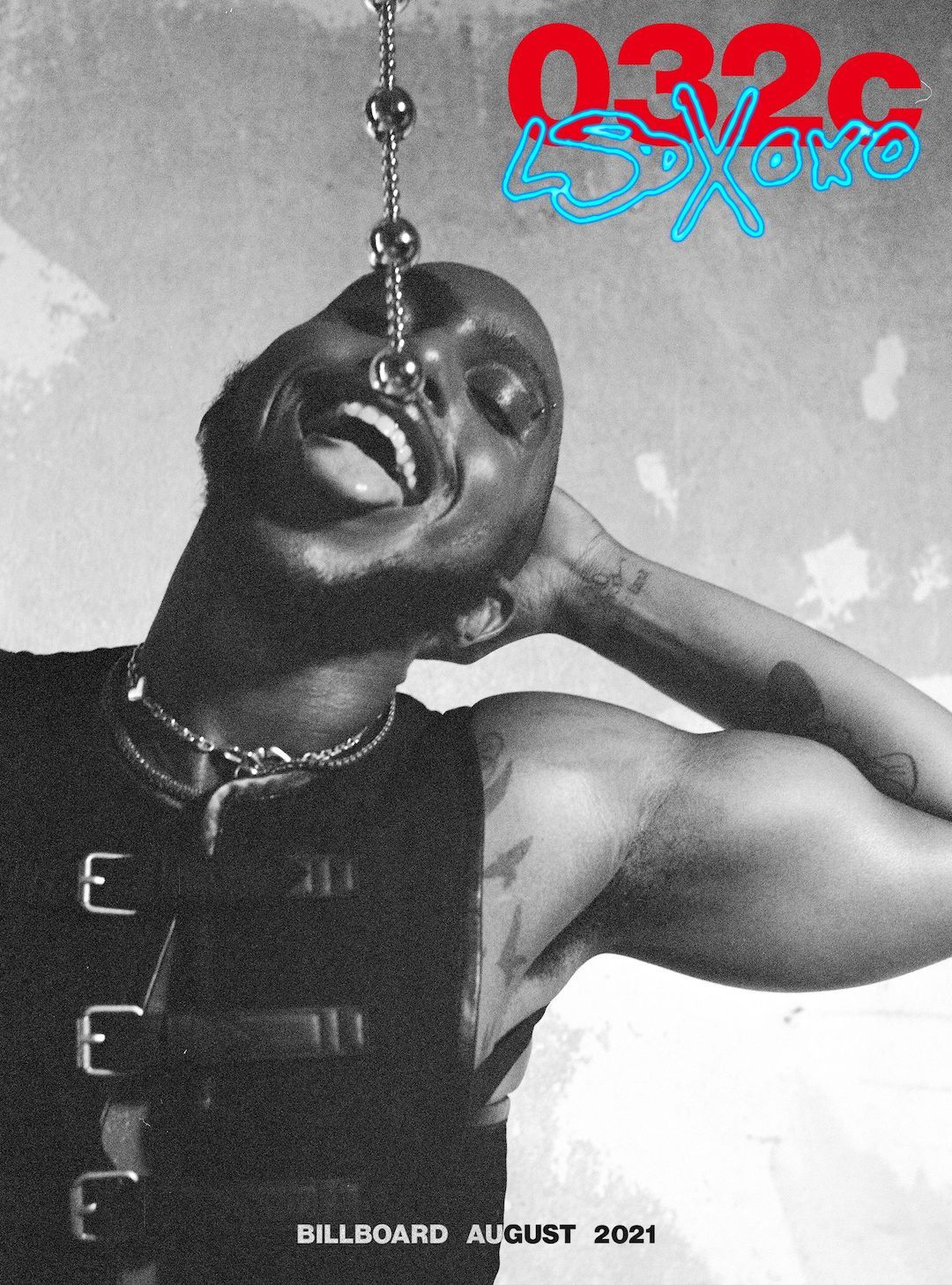

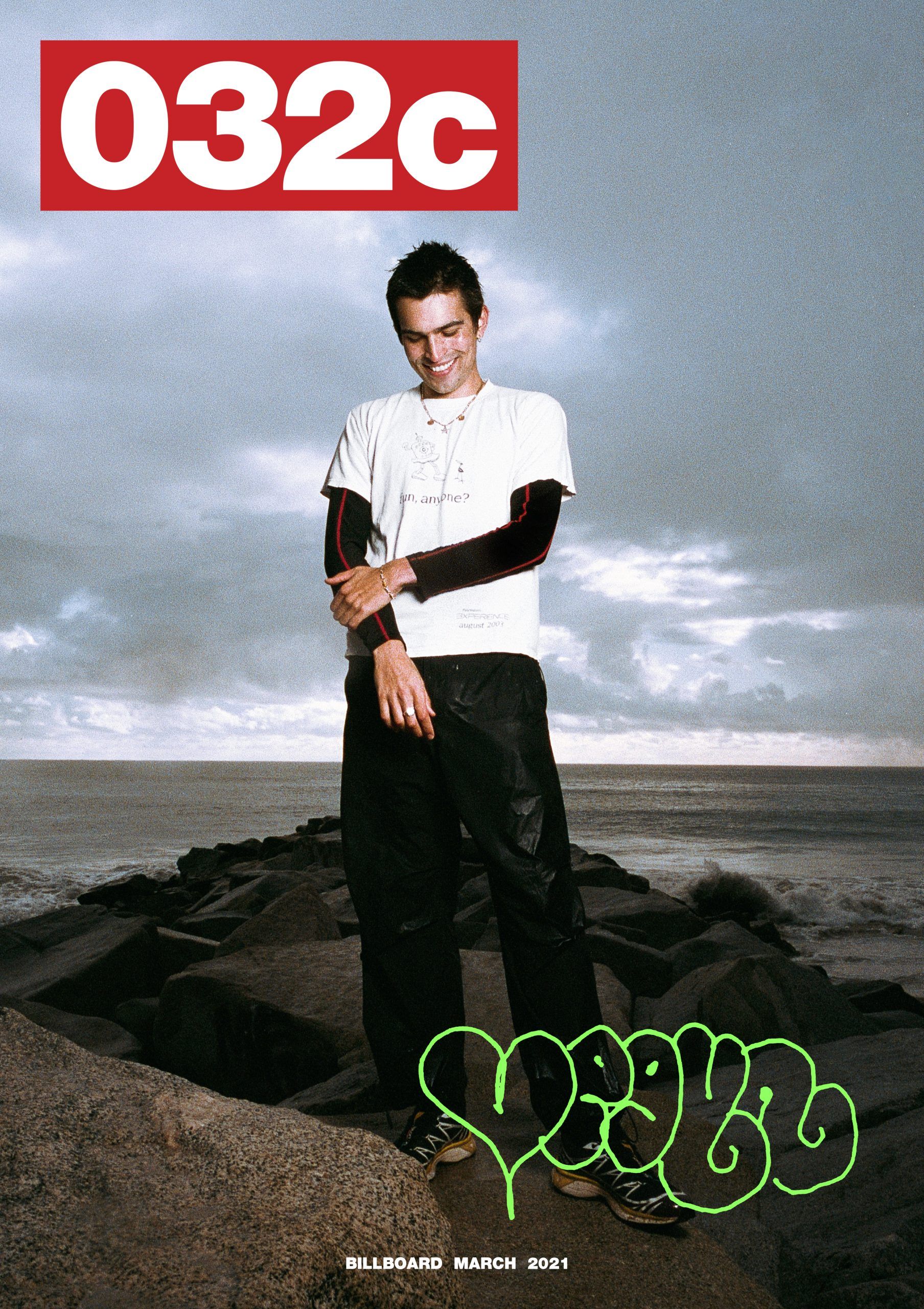

The rave as mosh pit: BAMBII’s INFINITY CLUB

|Phillip Pyle

For Toronto-based DJ and producer Bambii, embracing pop felt inevitable. “Pop veers into me because pop is so pervasive.” Since starting JERK in 2013—a bi-annual party fighting against pretentious techno purism and the industry’s whiteness by foregrounding queer people of color’s intimate, dynamic relationships with electronic music—the high priestess of the city’s electronic and queer scene has steadily worked toward producing her own earworms. Her first single, “NITEVISION” (2019), was a steamy, bass-thundering collaboration with Jamaican dancehall legend Pamputtae. Two years later, she began working as a producer on Kelela’s Raven, where she contributed her genre-fusing talents to late night club hits such as “Happy Ending” and “Contact.”

With the recent release of her debut EP, INFINITY CLUB, Bambii has come into a sound both entirely her own and inseparable from the communities she works in. An assemblage of techno, breakcore, jungle, dancehall, garage, and drum and bass, the eight-track project takes a diasporic approach to genre and collaboration. Its sound undulates like the shifting strobes, sideways-moving time, and mutating rhythms of a long, sweaty, memorable night out. The first track begins with a multilingual pastiche of voices introducing us to the “Infinity Club.” It’s a throat-clearing gesture, the shot you down before entering the expansive, exuberantly fun, and future-oriented world of Bambii’s creation.

PHILLIP PYLE: How have you seen Toronto change since you first started hosting JERK?

BAMBII: Just like any other city, it’s always in flux. In the most notable way, it’s become more unliveable. On the flip side, I feel like the queer community has tripled not only in size but in social power. The queer community is leading nightlife and culture in the city.

We had this illegal rave-era pop up in reaction to all the lockdowns that is obviously controversial, but that also radicalized listeners to hear sounds that they wouldn’t normally listen to. There’s this cult culture around partying that did not exist before. People are so dialled in attention wise that the energy is on 12. I rarely see that in other cities. When I go to New York, it’s cool but there’s a general sense of people being “over it,” bored, or distracted. You’re not going to get this cultish thing with everyone screaming, everyone paying attention at the same time. Toronto has that right now. When we throw these parties, everyone is on the same page. It feels akin to a punk show or being in the middle of a mosh pit.

PP: Is it ever difficult to keep one foot planted there when you’re having to travel all the time?

B: Because electronic music is such an institution and there’s a hierarchy between places—it’s a global scene but we perceive certain cities as legitimizing us—it definitely feels hard to plant myself in Toronto or, for lack of better language, to compete or grow in other cities. When I was younger, I really wanted to move to Berlin. Now, I feel quite the opposite.

It also just feels important on a cultural level that I am no longer putting these cities on pedestals. They are important, and I love that I have the privilege and access to go there as I wish, but I want to democratize dance music and complexify it, to say that it’s also existent in these places where there’s a lot of Caribbean people, a lot of POC—and that we don’t have to be trying to copy or appeal to the purism in other cities.

PP: Even in Berlin it’s exciting seeing these nights like “Floorgasm” pop up that are kicking back against techno purism.

B: Floorgasm is an amazing night. But, yeah, the idea of pure techno feels so made up. Sometimes I see techno stuff and I just feel like everyone’s lying, and I’m like, “You guys like this? It’s been FIVE HOURS!”

PP: Your newest project, INFINITY CLUB, has been out for a month. How does it feel listening to it now?

B: I do, weirdly, interact with it as a passive listener. Sometimes I’ll literally just put my own song on because that’s what I want to listen to walking down the street. I still feel alienated from it or in disbelief, but it essentially feels good. It does feel like I’m standing on some pillar of self-belief that I wasn’t on before. I also feel in need of expressing myself more. When I finished, the first thing I wanted to do was make more music.

PP: Is this music a natural extension or a pivot from INFINITY CLUB?

B: Natural extension. INFINITY CLUB is a concept that I’ll be expanding on. Because the project is everything and nothing, I can go in any direction I want. It hasn’t essentialized itself as any one thing. That’s important for me as a producer. With the way we consume music, things have to be packaged in a very particular way for people to understand, for the music to reach people. I’m trying my best to resist that rule in the industry in whatever way I can. Obviously, there’s this outside influence of feeling like your ideas need to be consistent with previous ones. This is capitalism subconsciously seeping in and influencing how you make things. I’m constantly challenging myself to resist being essentialized and to resist reduction.

PP: You’ve often noted how important it was to be exposed to various global cultures and music genres in Toronto. How do early memories of listening to music figure into making your own music?

B: I’m an only child and I spent a lot of time alone. I wasn’t allowed to be out and about like that, so I spent a lot of time listening to music and obsessively replaying songs over and over. Being obsessed with very small parts of songs—that’s one of my first memories.

As I’ve come into making music, that memory have translated into an obsession with earworms, any kind of chordal information, or a loop of a song that feels good in repetition. The best moments of when I’m making music feel reminiscent of being a child and listening to a loop I really like.

PP: In addition to bridging all these electronic genres—techno, dancehall, jungle, etc.—INFINITY CLUB leans into pop production and song structures. Did you plan to veer into pop?

B: Pop veers into me because pop is so pervasive. We have no control over our consumption of pop culture. All my knowledge of pop culture and pop music is involuntary. I’m forced to know what Taylor Swift is doing. But, she does not have my consent!

One thing that’s good about pop is that the structure creates shared memory and collective engagement. I love ambient music and things that are experimental, but the parts of songs that people can latch onto are always going to be important to me to recreate. You can say whatever you want but the best moments in the club are when you and your ten friends are screaming the lyrics of the thing that everybody knows. I love call and response. Now every time I play “NITEVISION,” everyone is playing off the call and response in the hook. That is something that lasts forever. No matter where I am in the world, I always have that moment with people when I play that song.

PP: Foregrounding Caribbean and Black diasporic communities, especially the Jamaican diaspora, is key to both your music and JERK. I’m wondering how this translates into the process of collaboration?

B: By having artists such as Lady Lykez. I always champion her and bring her up in interviews because she is an embodiment of things past and present in Caribbean culture. She is this powerhouse vocal. She can sound like Spice or Lady Sovereign. She has these very electronic sensibilities and can be on nearly any style of production. That’s been important for me because there’s this nostalgic lens that people view Caribbean culture through that feels so oppressive and annoying. Any time someone’s trying to communicate that something is Caribbean, or referential of Caribbean culture, the references are so old. This is such a cultural condescension that happens not just to Caribbean people, but to diasporic people, Black and non-Black, where culture that is not white is continuously simplified in media. We only see whiteness as something that can be futuristic or complex, and anything that is not white gets this nostalgic washing.

It’s been important for me to connect with Caribbean artists who embody the things that we grew up with, but who are also reaching forward into the future and subverting everything as we know it. That was important on INFINITY CLUB, both for the reasons I mentioned and to ground electronic music back in its origin point—because electronic music has been so removed from Blackness. And obviously, there’s dialogue where people are saying “make techno Black again,” but I am traveling to these festivals, I am playing on these bigger and bigger stages with primarily white crowds, and I can feel the pushback. It’s like I’m the outsider in something that is more or less my culture. INFINITY CLUB is organically speaking to the relationship that is always there. People try to obscure it or break it apart, but the relationship is there.

PP: Have you noticed any changes in awareness surrounding electronic music’s relationship to Blackness since you started DJing?

B: I couldn’t full-heartedly say that. If we’re talking about Europe, I see a slight shift in bookings. But I do think that there’s a level of tokenization. It feels like there’s a few people who are being selected, who have to reach a level of excellence that is not required of their white peers. It feels like there are always, like, 20 white techno guys who can just truck along while being unremarkable.

There are changes, but I’m looking for normalization, not for a few people being picked. I think people confuse those things, and I’d say that goes for the whole music industry. Anytime there’s someone marginalized in the music industry, we hyper focus on that. The hyper fixation means that they can be the only one who operate in that space at any given time. Really, we should allow a variety of bodies to be famous and have access, and not have to write 30 think pieces on it and call people “brave” and blah, blah, blah.

PP: INFINITY CLUB unfolds as more than a sum of its parts. It’s dynamic, internally, in terms of tempo and genre, but it also feels inseparable from the parties that you organize outside of it. How do you balance all the parts of your practice when trying to focus on a single project?

B: That’s a good question because I don’t feel like I know. I feel a lot of anxiety around things that require different muscles or to lean into different practices. I would say being an artist is a completely different modality than being someone who curates space or DJs. I think they can benefit each other but, in terms of how it works out in a pragmatic sense, it’s super difficult. We’re living in a really content hungry era that requires artists to overshare. With that, on top of what you just said, it feels almost impossible.

Doing something like JERK requires me to be of the collective. Being an artist requires me to be outward facing and it requires me to be very into me. It’s so much self-propagation. It feels funny and hard switching all the time, and trying to make sure one thing is fed and the other doesn’t suffer. I don’t know if I have figured out how to do that yet. No matter what I do with music, though, I’m never going to stop doing JERK. That’s a promise.

PP: You’re planning a night with five of your biggest inspirations in music. Who would you put on the bill?

B: I would do Shygirl, Stefflon Don, Kikelomo, Teeno, and… can it just be me?!

Credits

- Text: Phillip Pyle

- Creative Direction: Bambii

- Photography: Kirk Lisaj

- Photography Assistant: Chinelo Yasin

- Styling: Angie Jayasinghe

- Makeup: Ms. Myles