Ways of Raving: Geoffrey Mak on Empathy and Psychosis

|Shane Anderson

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture” is a phrase attributed to anyone from Thelonious Monk to William S. Burroughs or Miles Davis that characterizes the impossibility to write about another art form. And the same seems to be true about raving. How can you approach such a social collective experience in a single person’s words?

Edited by Zoë Beery, Geoffrey Mak, and McKenzie Wark, the recently published collection Writing on Raving (2025) proposes a number of answers: writing about raves through personal essays, fiction, poetry, and critical pieces. I sat down with one of the editors, Geoffrey Mak—a frequent contributor to The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The Guardian as well as author of Mean Boys (2024)—to discuss the book as well as his own writing practice, but the conversation kept expanding, addressing how he escaped psychosis, the blackhole of social status, cancel culture’s evangelical roots, and why raves are the new churches.

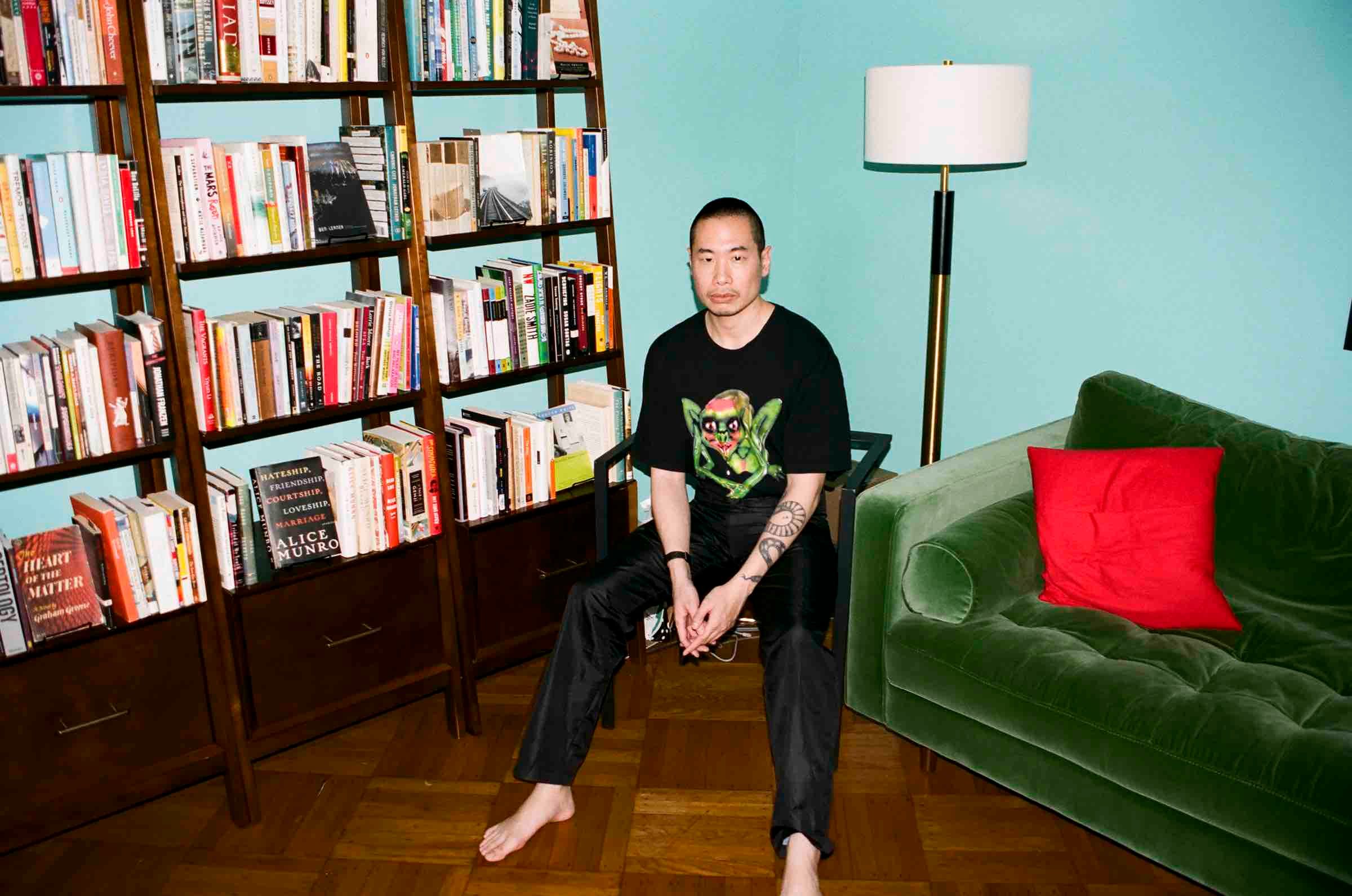

Geoffrey Mak, Photo: Acudus Aranyian

Shane Anderson: What was the impetus for Writing on Raving?

Geoffrey Mak: The book is a side-project of a reading series we started over three years ago in New York. At the time, we knew a lot of writers who were writing about raving, but weren’t necessarily getting published, and so we wanted a place to share their writing. Zoë Beery used to do programming at Nowadays and so we thought: why not just do a reading there? We read at that event, and invited Linn Tonstad, Daniel Martin-McCormick, McKenzie Wark (who read from what would becoming her book Raving) and Emily Witt (who read from what would become her book Health and Safety). We were only going to do one but hundreds of people showed up to the event. There wasn’t even enough room on the dance floor for people to listen. It was pouring out into the bar. So, we knew that there was a huge audience for this. For the next one, McKenzie joined Zoë and me, and as a collective, we have produced 16 events in three different cities.

Since the beginning, we always defined our project as a folk art. Our medium was community-building, and the artifact was writing. It wasn’t the sort of “high art” thing we saw in academia that got passed down by gatekeepers. It was something we were doing on our own that was specifically for our community and by our community.

SA: But why folk art?

GM: Because it’s a social form of art to describe the rave, which is a social space. It’s not a performing arts experience where you show up, watch some performers, have an experience, clap, and leave. At the rave, it’s not clear who the performer even is. Is it the DJ or the dance floor? Who is serving who, or is that not even the relationship? There are so many different ways to look at the rave, which is what we wanted to document in the anthology. We wanted works of writing to approach the rave from every different angle we could find—personal essays, academic criticism, journalism, fiction, and poetry.

SA: Why does raving need to be written about? I’m guilty of this myself in my last book, but couldn’t one argue that it doesn’t need “high art”?

GM: Oh, but I don’t even see the anthology as “high art.” Most immediately, it’s documentation of a moment in time we participated in. Without that, it will just disappear and be forgotten and potentially distorted.

Here’s an example: With the Ghost Ship fire, the media seemed to have their own idea of what was going on, painting this picture of hedonists who went too far, leading to disaster. Michael Chabon was even supposed to write a screenplay for a movie about this—and everyone got really angry, saying, this is not your entertainment, this is our mourning. But a lot of the people who went through that experience weren’t writing about it. And so, it was really important for us to have Chris Zaldua’s piece, which documented it. Working with Chris on that piece was such an intense and emotional experience, and so it was also about healing.

Writing on Raving edited by Geoffrey Mak, McKenzie Wark, and Zoë Beery

SA: So, a lot of it was about creating a time capsule. That also feels relevant to your book Mean Boys (2024).

GM: Yeah, I did intend for it to be a time capsule but it also feels very relevant today. That book is so creepy because it was about the first Trump administration. During the Biden years, I thought of it as a period piece—all that felt so long ago. But now in the second administration, we’re going back to a chaotic era where the means of communication have been changed by platforms built on this old ideology of disruption—with Trump positioning himself as someone who’s going to disrupt the elite, echoing the Silicon Valley ethos.

SA: At the same time, the book is a series of personal essays.

GM: I love the personal essay for being such an expansive and elastic medium or genre. And it was important to me to have all these different kinds of forms that the personal essay can take on throughout the book. When I was younger, I read James Baldwin and Joan Didion and loved how they used their personal experiences to tell stories that were relevant to an entire nation. I was always impressed and moved by that gesture. So, I wanted to do that in the book.

SA: It definitely feels like you captured the tenor of the first Trump era with the stories you told, including your own.

GM: Hegel and Lukacs talk about the spirit of the age; and in retrospect, I felt like I was channeling the spirit of that age. These are times of mass paranoia and conspiracy. And one of the major events of my life I write about was my descent into psychosis, paranoia, and conspiracy at that time. My psychosis took place during a collective psychosis. It felt important to document that and also work through it, on the page, so that others would see how I got to the other side, that it was possible to move on.

SA: It’s interesting because on the one hand you explore the art world and party life in Berlin but then you make a hard cut to Elliot Rodger, who killed six people during the Isla Vista killings in 2014. It was quite jarring and like he became a distorted funhouse mirror of what you were depicting in the essay before that.

GM: Haha, yeah the transition is kind of jarring. One of my grad school professors came down hard on me for doing that. I wasn’t planning to write about Elliot Rodger originally but my process is that I write something down and then I find the heat spot. I might not understand it but I pursue it to understand why something lit up inside me. In these essays, you can see me working through ideas on the page that are unresolved at the time I was writing. And so, in the last essay, “Mean Boys,” I was writing about moving to Berlin and my social education but then I had this revelation that normally we think about financial class and identity but there’s this third thing—status. This was something I really witnessed in the art world. There are people who aren’t privileged in terms of class or identity but they have status.

This gave me a new lens to see my curiosity about Elliot Rodger, the incel mass shooter. Partly because he was Asian American. So, I read his manifesto and it was extremely striking to me that he wrote about a life where he didn’t have status and that this grievance pushed him to commit mass murder. He came from a wealthy family, he was half-white, so he had identity and financial privilege. So why didn’t he love his life and excel? It came down to status.

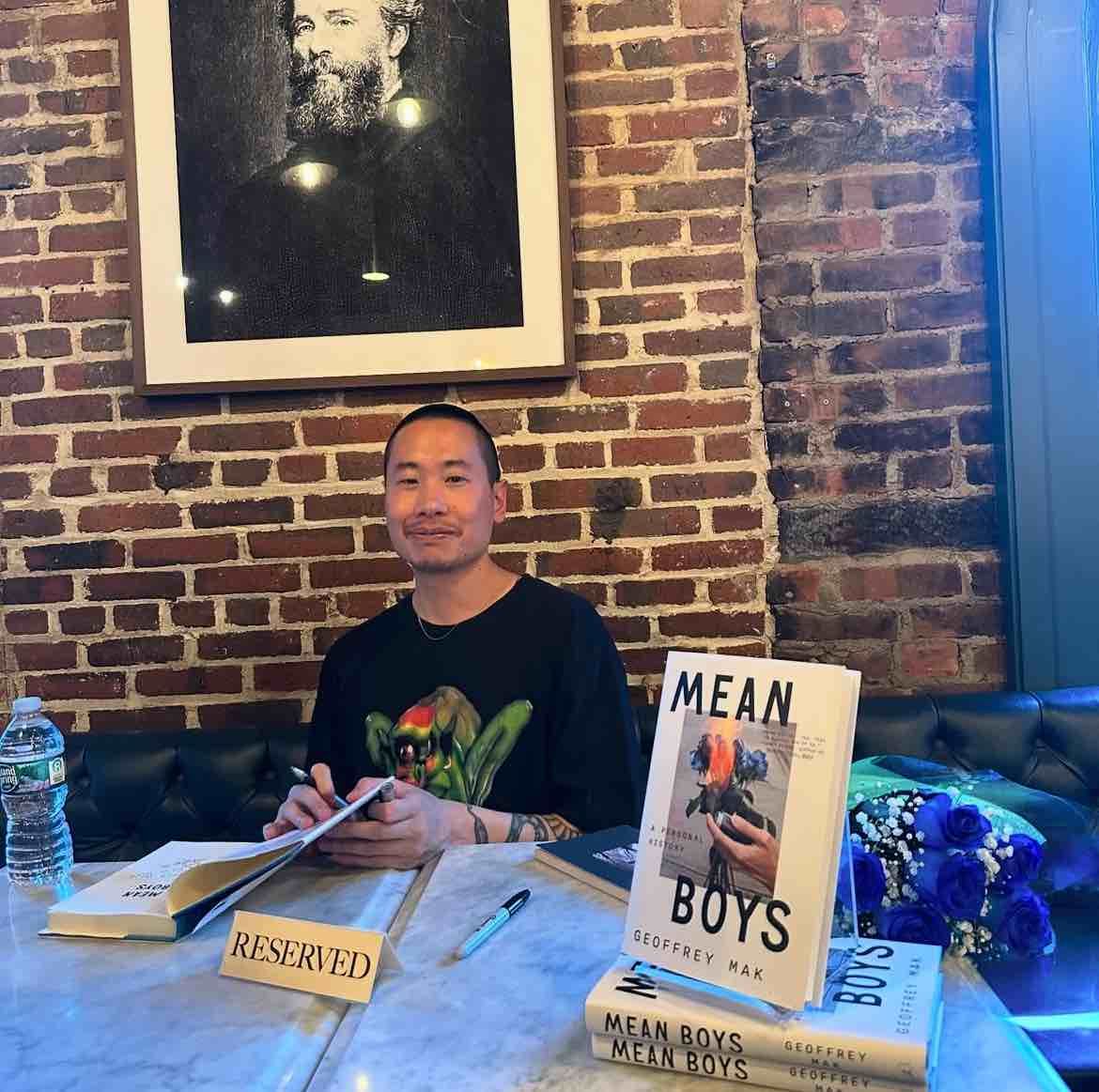

Geoffrey Mak at the McNally Jackson Seaport reading of his book Mean Boys: A Personal History, Photo: Garrett Traya

SA: So, status is more important than wealth or identity today?

GM: I think it’s more volatile. We’re in a weird period—Sean Monahan from K-HOLE talks a lot about how we don’t have fixed markers of social status anymore. Wealth cannot necessarily buy social status and there’s a lot of insecurity and panic right now about how to defend it—a lot of people like influencers live off it, which is why, I think our culture right now makes us more attuned to this than in the past.

America has created a political language about grievances regarding financial class and identity. But status doesn’t have a political language for its grievances, even though it’s political and has political consequences. Elliot Rodger is the extreme version that proves that point. He had a grievance around status but didn’t have a language for it and thus had no way to build solidarity around it. He couldn’t organize around it, but the grievance wouldn’t go away. I think a lot of people feel the same way—say in the manosphere or the alt-right. There’s a huge panic of people going through what Elliot Rodger went through, but we don’t have a political answer to it. And I think that makes it really urgent to find ways to talk about it.

SA: What should be done?

GM: A lot of Mean Boys started with the question: how do you talk to somebody you don’t agree with? The reason why conversation can’t happen is we don’t acknowledge each other’s reality. But if we don’t do that, we can’t communicate. We don’t need to condone the realities of these disaffected young men who share their experiences and we don’t need to affirm them—we just need to acknowledge them. And I think the book is trying to do that. Like if someone is saying they are in suicidal pain because they don’t have status, we have to acknowledge that that pain is real and take it seriously. We can only have a conversation if we acknowledge that we’re speaking in a shared reality.

On the left, solidarity is such an important ethos and it’s built on the idea that you can identify with the needs of other people, even if they don’t directly affect you. And so, if you can identify with the incels or alt-right trolls, you can build solidarity with them and their grievances. This would then open a door to a whole field of solidarity and alliance.

SA: “Love thy neighbor.” Which is interesting, because you’ve also written about returning to Christianity.

GM: Christianity is both an answer and a huge trap. I mean, what you’re seeing right now on the left are these leftist purity tests and cancel-culture and that definitely comes from the Evangelical Church. So, in a way, the right adopted transgression from the left and the left adopted the moral majority of the Reagan era. It’s what happened with “PC culture” in the 90s. Again, it’s a total trap.

If you have purity tests and shut down conversations and cancel people, then you have a deeply fractured society that is totally playing into the playbook of the neoliberal regime and the market, which fragments society and alienates everybody.

But again, solidarity as an ethos of empathy and identifying with others’ needs…it’s pretty Christian. It’s secular too and also a little moralistic, which I’m uncomfortable with, since moralism is almost always a trap. But I do think there needs to be some kind of ideal that people aspire to in a moral sense. I think that needs to happen before we get out of this mess that we’re in in the States.

SA: I see what you mean. I recently took part in Cem A.’s Crit Club project at K21 in Düsseldorf, where we had to debate which was more important, contemporary art or modern art, and had to both lambast and defend each. It was an interesting thought experiment, because there was no notion of identification—you just had to explain what made each interesting. Long story short, when I had to defend modern art, I said something about how artists were once allowed to be complicated and the person arguing for contemporary art in that round said, you mean misogynist. It was interesting to me because that perfectly mirrored our level of discourse today—this immediate attempt to shut something down if it’s impure. But people are complicated, and we all have our dark sides. It just seems like we aren’t allowed to talk about them anymore. We always have to be on the right side of things, which creates anxiety.

GM: I think one of the problems is that when you look at literary modernism—and lump Expressionism, Surrealism, and everything together—it prioritizes the subjective experience as total. I think that’s very relevant now. We all basically live in our own filter bubbles, we have our subjectivities, but we can’t break through them and access a shared reality. The first step now is to acknowledge that there are other realities and other people experience different things. Other people have real pain that we don’t experience as our own. That pain needs to be acknowledged as real.

This has been part of my journey after psychosis. When you’re really in the thick of psychosis, you place yourself in the center of the universe. Everyone’s conspiring against you and everyone who doesn’t go along with what you believe is lying. So, one of the most important questions is how to break out of that. I think there are very few universals in life and I think pain is unfortunately one of them. You might even call it the lowest common denominator of social relations. But if you have that, then you can move outward into other’s people’s lives and empathize with them.

Mean Boys: A Personal History by Geoffrey Mak

SA: I’ve mentioned this elsewhere, but there’s this Baldwin quote I really love where he says: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive. Only if we face these open wounds in ourselves can we understand them in other people.”

GM: It’s funny that you bring up Dostoevsky and Dickens because nobody writes novels like that anymore. Today, we mostly have novels that are 200 pages told entirely from one perspective. In those old novels, you had different worldviews and voices that were clashing with one another. And I think that’s a sign of our times.

SA: Yes, but—and this touches on what the other person at the Crit Club was suggesting—nowadays you can’t write from someone else’s perspective. It would immediately be understood as appropriation.

GM: It’s really tricky, true. I think we’re in an age of situated knowledge, which pressures the writer or critic to only look at their own experience. Yet, I just read Ben Lerner’s Topeka School, which has these really long passages about his parents told from their point of view. I later read in an interview that he worked very deeply with his parents on the book. They had read about 20 different drafts of a book that is like 80,000 words before they got the character right. I was really moved by that because it seems to have an ethical answer about writing about other experiences. You have to listen. You have to talk to people. You can’t just write your version and show it to people an expect them to co-sign on it. Involving others takes a lot of time but it’s the right way to do it.

With Mean Boys, I pissed so many people off. I lost some friendships.

SA: How?

GM: I didn’t write from anyone’s perspective but I wrote a lot about other people’s lives and they didn’t necessarily consent to it.

Emmanuel Carrère said that writing about yourself and other people is like tickling. If you tickle yourself, you can always decide when it’s too much. But if you’re writing about someone else and they don’t have the control over when it will stop, then it’s total panic. I own that I didn’t do this responsibly but I want to develop a practice where I’m more engaged with the people I write about and make it a two-way conversation.

SA: Are you writing anything now?

GM: Yes, I’m working on a novel that’s set in Berlin about a trans raver girl who joins a cult, but she doesn’t know it, until it’s too late to get out.

SA: So, we’re back to raving. It seems to be one of the big themes.

GM: I guess it’s because in our ultra fragmented world it’s really hard to find places of spontaneous social life. It doesn’t really happen online anymore, and platforms are replacing the role community used to have in our lives. I think people used to go to church for this. And when you hear that people say that they miss religion, it’s actually the community that they miss more than God. And so, finding new ways of building community is an extremely important question today.

Raves are really great because you don’t get to decide who shows up. There can be a bunch of people you don’t like and would never talk to, but when you share the same dance floor, there’s this kind of intense intimacy that often happens. A lot of emotions will happen across the dance floor at exactly the same time because you’re so in tune with the rhythm and the music. And so, you have a kind of intimate knowledge about everyone around you. I think raving formulated my idea of community but also my idea of how political organizing could be. It doesn’t mean raves are perfect. There are many dangers in community and communal thinking. There are certain mechanisms at play in raves, such as not protecting the outsider and suppressing dissent. These two sides are what I’m exploring in my next book.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson