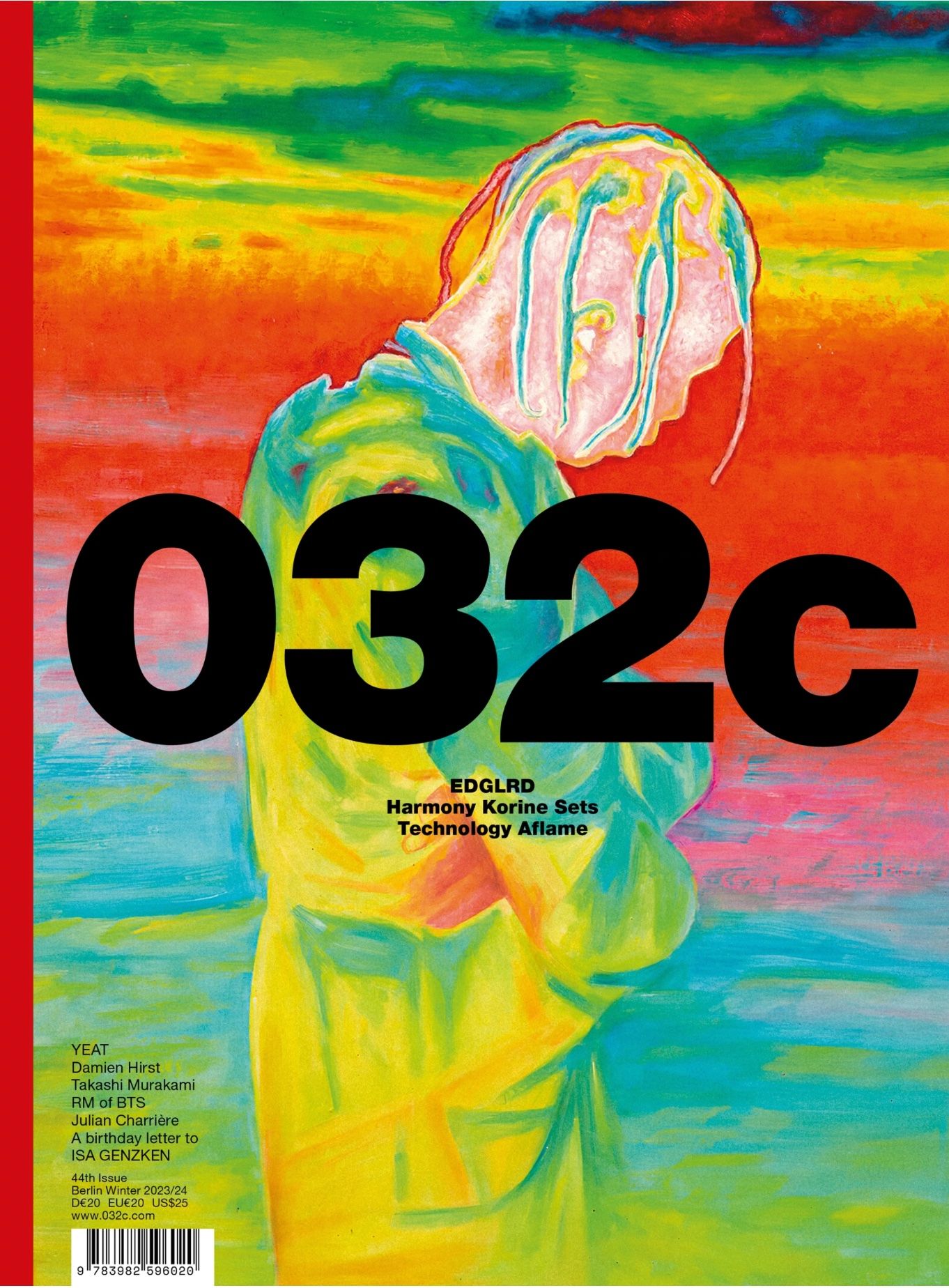

EDGLRD: Harmony Korine Sets Technology Aflame

|Cassidy George

Welcome to the world of Harmony Korine. For decades, the filmmaker launched an all-out assault on the industry, forever changing how we perceive the medium. And now, Korine has launched his creative studio EDGLRD exploring the future of stories in the age of AI. In this dossier from our issue #44 , Cassidy George delves into Korine’s past and what the auteur has in store for us in the future.

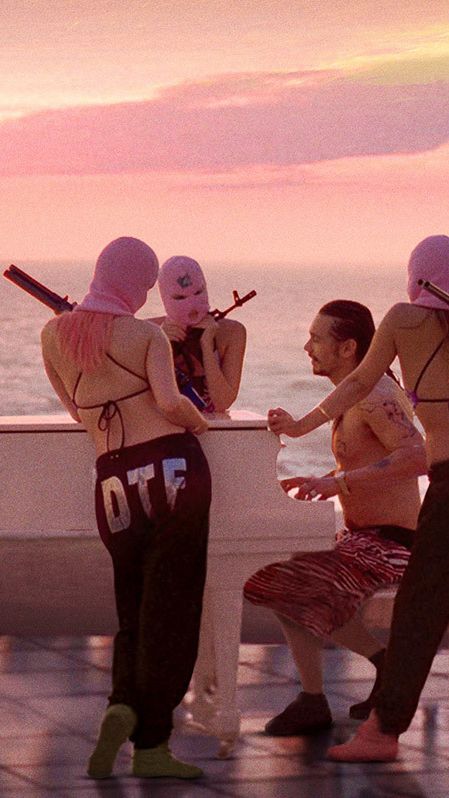

Harmony Korine’s latest feature film, Aggro Dr1ft (2023), was created with his new design collective, EDGLRD. It stars actor Jordi Mollà as BO, an assassin who has to undertake one last dangerous mission before retiring

There are many ways to describe HARMONY KORINE: auteur, raconteur, provocateur, painter, skateboarder. Most crucially, though, he is someone who is bored with movies.

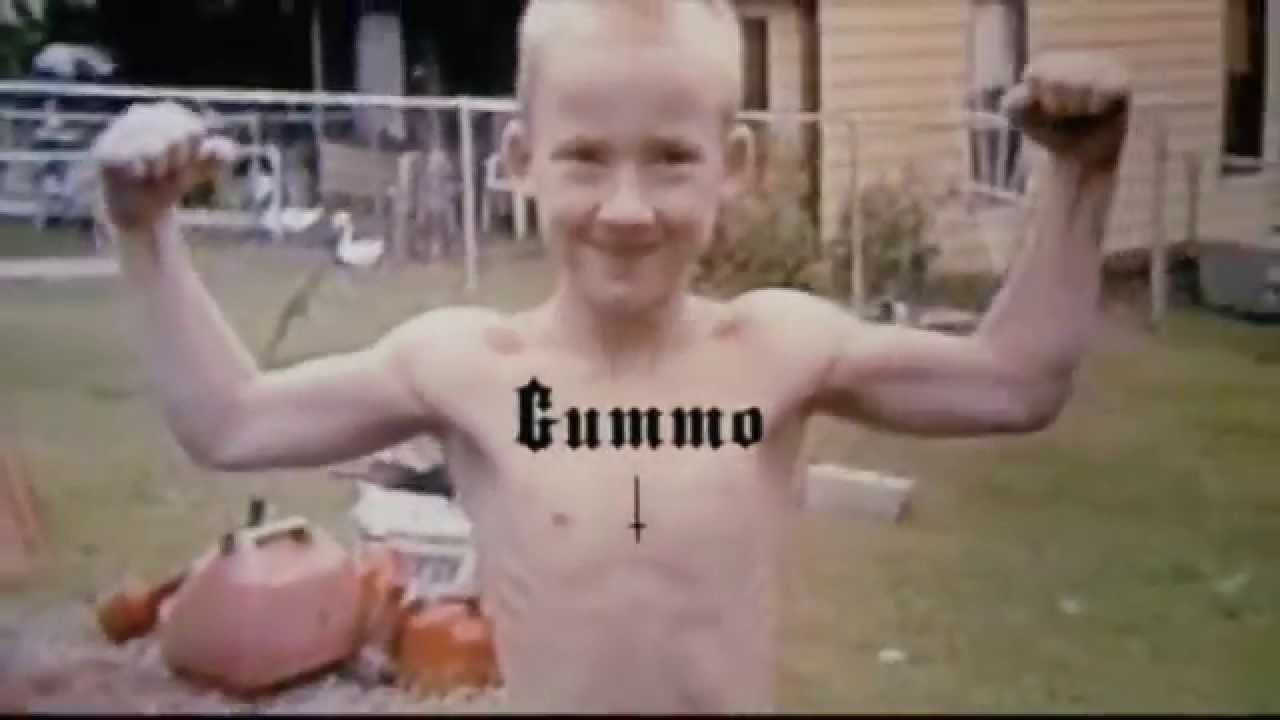

This is nothing new for Korine. He has been proclaiming it loudly in the media since the 1990s, when he wrote the script for Larry Clark’s film Kids (1995) at just 19 years old and then directed two of the most original films of the decade: Gummo (1997) and Julien Donkey-Boy (1999). Enraged by the “mediocrity” and “denigration” of what he believed to be the century’s most powerful art form, Korine’s cinematic journey has been paved by a yearning to destroy old structures and conventions, as much as it has been to create the images and stories he hadn’t yet seen. With the release of the box office hit Spring Breakers in 2013, Korine was able to achieve his lifelong artistic aim: to infiltrate, or even infect, mainstream pop culture with his own visual and conceptual agenda. Korine’s work is now as at home in the music videos of Rihanna and the campaigns of Gucci as it is on the walls of Gagosian or the Centre Pompidou, where Korine was the subject of a blockbuster solo show in 2017.

Korine, who turned 50 this year, has the world at his fingertips. He casts rappers – including Gucci Mane, Snoop Dogg, and Travis Scott – as peripheral characters in films with ease, has made a sport of turning down jobs from luxury fashion clients, and has world renowned gallery representation (as of this year, he left Gagosian for Hauser & Wirth). For decades, Korine compared making films to warfare. Now, he has placed him self on the front lines of an even bigger battle: shaping the future of entertainment. Korine is no longer concerned with disrupting or salvaging cinema. He’s interested only in what comes after it.

A GLOSSARY OF HELPFUL TERMS FOR UNDERSTANDING HARMONY KORINE’S PAST

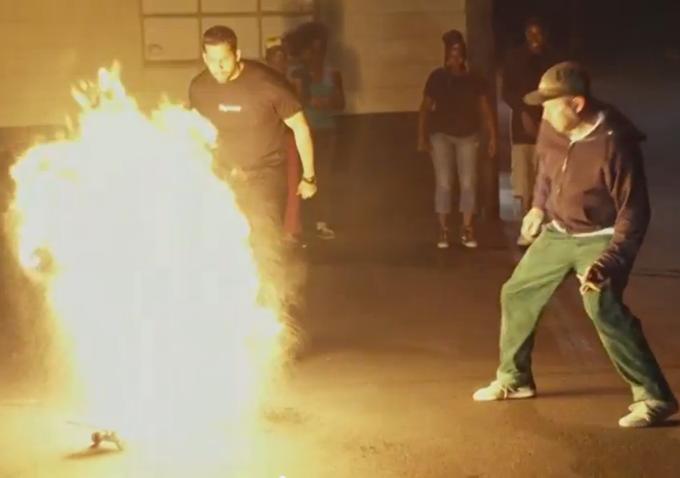

FIRE

When Harmony Korine was young, he felt as if he were on fire. Driven by a compulsive desire to create, Korine was gifted with the curse of an artist’s mind that’s akin to restless leg syndrome. With his brain flooded by a constant stream of words, images, and ideas, young Korine was in a constant state of overwhelm.

“It was impossible to shut my brain down. All I wanted to do was make things,” he told journalist Eric Kohn, in 2013, of the years when he lived in his grandmother’s house while attending New York University. “I’d sit in my grandma’s house and paint all day. I’d cut things up, make collages, sing into tape recorders, play the banjo into my answering machine. I’ll tell you how obsessive I was: I would literally change my answering machine, like, once every hour.”

As the son of a documentary film maker, Korine moved from Nashville to New York with an almost encyclopedic knowledge of film history. Living far from campus meant spending all day in Manhattan, where he would watch back to back movies at St. Mark’s Theater between classes Holding reverence almost exclusively for directors including Buster Keaton, Jean Luc Godard, and John Cassavetes, Korine yearned to make films as much as he raged at commercial movies in the 1990s.

There has also been a great deal of actual fire in Korine’s life. He has claimed that three different houses he’s lived in have burned down. Korine says he is responsible for only one of those fires, the one at his grand mother’s house in Queens, where he fell asleep with a lit cigarette in his mouth.

FRAGMENTS

Korine, who famously loves stories and hates plots, studied dramatic writing at NYU. Although he dropped out after one semester, the time he spent studying Aristotle and Sophocles proved useful. Understanding the “rules” of narrative structure made it easier for Korine to ensure he would be able to break every one of them.

His directorial debut, Gummo – which is really just an assemblage of scenes, images, sounds, and disparate thoughts and conversations – was like a declaration of war on traditional storytelling. It created space for the radicalism of “cut’n’paste,” a technique that links Dadaism to punk zines, in a completely unexpected forum: the run of the mill movie theater. Korine has compared his approach to narrative as being similar to the experience of looking through a photo book, in that the gaps between images allow the viewer to find meaning by association. He employs this technique in his other artistic practices. His first book, A Crackup at the Race Riots (1998), is also a pastiche that combines a list of future movie ideas (“A former prostitute with a low IQ poisons her priest”) with potential suicide notes and a fake letter from Tupac Shakur to a 19 year old German fan.

His narrative politics are also in formed by a personal lack of patience that foreshadowed the dwindling attention spans of the future. “I didn’t want to waste time getting to the good part,” he told GQ in 2019. “I wanted every single thing to be the good part.” His work does away with rising and falling action and aims to create a constant stream of highlights, which mirrors the ways that digital feeds distribute content today.

“It was impossible to shut my brain down. All I wanted to do was make things.”

– Harmony Korine

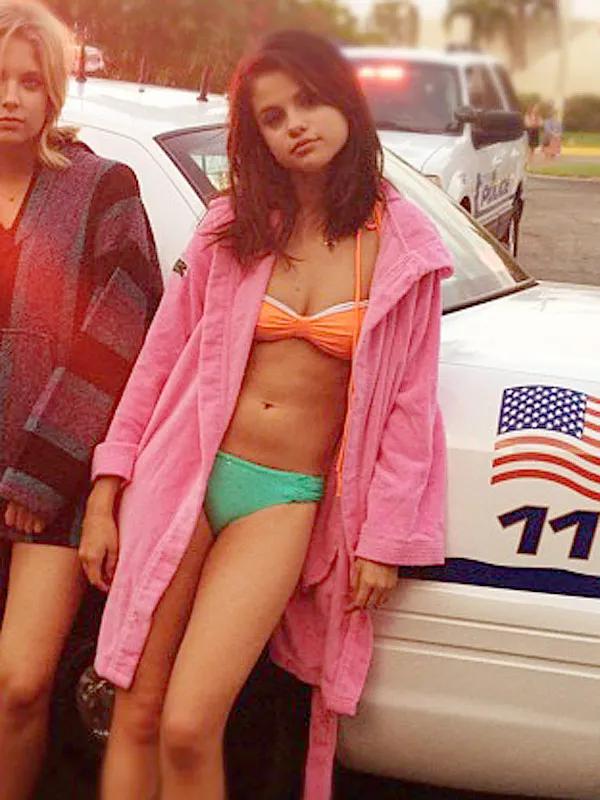

As Korine has aged, the sharp edges between cuts and scenes have smoothed. Spring Breakers (2012) is built on what Korine has called a “liquid narrative,” wherein music serves as the spine of the story. Although the film was released years before TikTok or Instagram Reels were invented, the moody stream of imagery and content eerily mirrors in app experiences today.

Each of his scenes is designed to function as a complete story, which can be pulled out of the film and viewed independently without losing any of its merit. The success of Korine’s endeavor was proved tenfold on Tumblr, where clips from Spring Breakers circled incessantly in the 2010s – and helped shape the aesthetic culture of the platform.

FABLES

“I’ve always seen everything as one thing, a unified aesthetic. The films were tied into the books I was writ ing, which were tied into the art I was making, and the way I spoke to people,” Korine told Kohn. For Korine, there was no separation between his art and his life, which he viewed as a performance. As the writer of Kids, Korine became an overnight sensation. He used the incessant curiosity and attention from the media to hone a new craft: fucking with the press. In countless interviews with major publications and three memorable appearances on The David Letterman Show, Korine played a caricature of himself in the public eye and stoked the flames of his own mythology.

In the 1990s, writers reported Korine’s antics during interviews. This behavior included tap dancing for them in shoes that were many sizes too small, wearing wigs that were just exaggerated versions of his own hair, offering journalists and waitresses bumps of drugs, throwing poppers at the feet of pedestrians and busboys, threatening to break the legs of any one who misquotes him, and attempting to stab a Vogue writer with a fork.

Just as he does in his scripts, Korine artfully blurred the lines between fact and fiction. He left anyone watching or listening unsure about where reality begins and ends – and questioning whether what’s “true” even matters. “I don’t know how to tie my shoes. A kid at school tried to teach me once, but that same day I almost drowned in quicksand,” he told New York Magazine in 1995. In his official bio for Miramax (which distributed Kids), Korine claimed that he grew up in a traveling carnival and that he was the grandson of one of the original Bowery Boys, a notorious gang in antebellum New York City. In later interviews, he claimed his parents were Trotskyites who firebombed houses, and that he spent years living with a cult of fishermen in Panama who were hunting for mythical fish.

“I’ve always seen everything as

one thing, a unified aesthetic.”

– Harmony Korine

For Korine, public conversations were just another form of storytelling – another opportunity for invention. An unidentified friend of Korine’s is quoted by The Guardian in 1999 as saying, “The odd thing [about Korine] is, the stories that are the most unbelievable are often the ones that turn out to be true.”

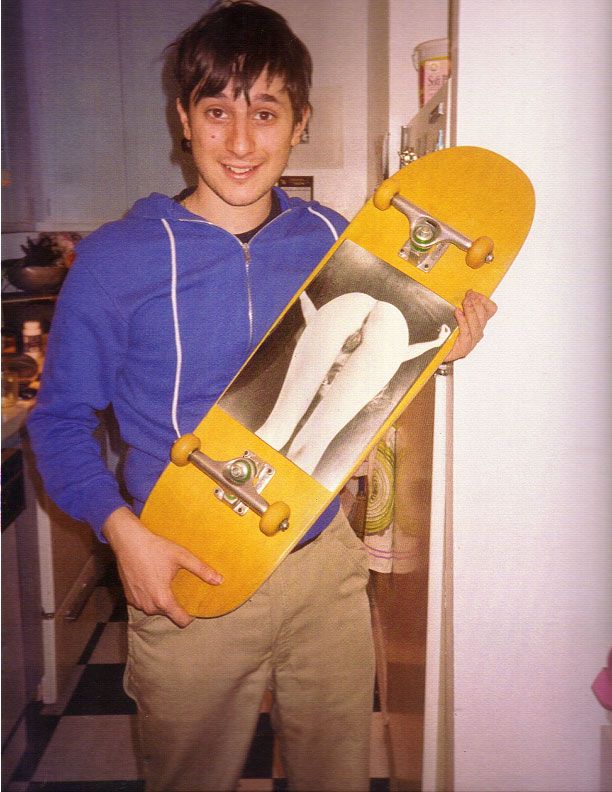

SKATEBOARDING

Korine started skateboarding as a teenager in Nashville. Back then, it wasn’t just a hobby or a sport – it was a controversial subculture associated with teenage delinquency. Korine told Vice in 2017: “Skateboarding in the late 80s or 90s in the South wasn’t something that people aspired to do. It was much more looked down upon. We were spit at all the time. Fights were a daily occurrence. It was much more about violence.” Both Korine’s aesthetic sensibilities and his general disposition – a deep knowledge and attraction to street culture, a comfort and yearning around exploring pain and the limits of the body – are connected to his love of skating.

The skateboarding scene in New York in the 90s was also the breeding ground where Korine’s career blossomed. While hanging with fellow skateboarders in Washington Square Park, Korine got introduced to photo grapher Larry Clark, who would later ask Korine to write the script for Kids. The dialogue in the script, which Korine wrote in his grandmother’s basement over the span of a week, was based on the speech patterns and behaviors of Korine’s friends, Harold Hunter and Justin Pierce, who also acted in the film and skateboarded professionally.

The story, which follows a group of skate rats as they talk smack, get high, and unknowingly infect virgins with HIV, feels so disarmingly natural that many viewers thought it was a documentary. Now viewed as an essential contribution to the cultural his tory of skating, Kids is one of the few films that authentically captures the feeling of a bygone era.

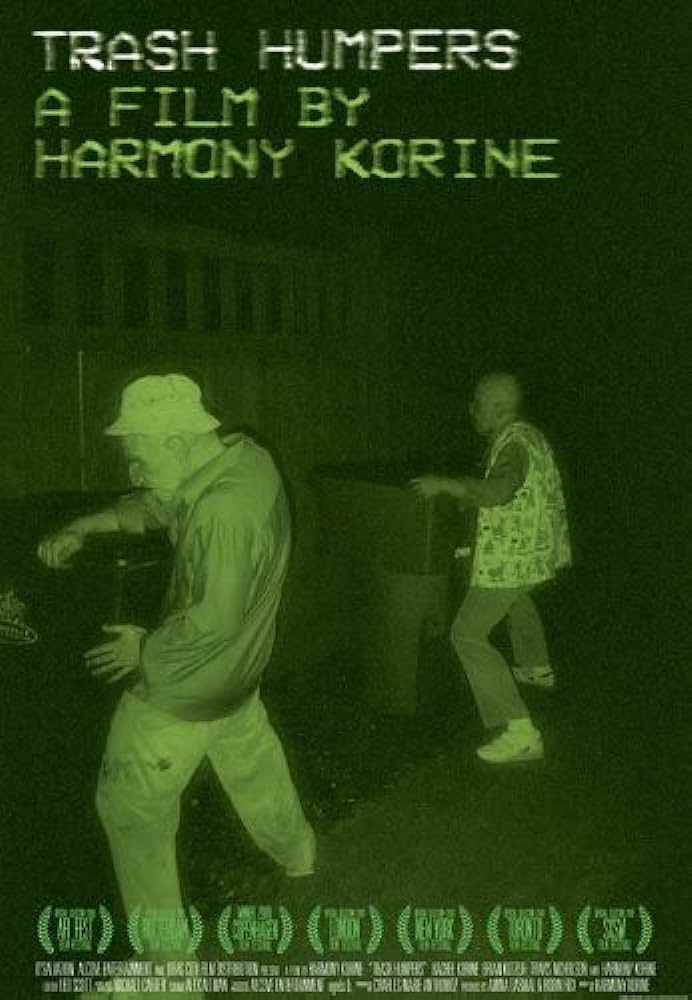

Skateboarding is a continuous thread in Korine’s life and work. He has released a book of zines with skater Mark Gonzales, shot multiple Supreme campaigns, and designed various skateboards over the years. His film Trash Humpers (2009) is inspired by skate videos, which Korine still watches daily. His firstborn child is even named Lefty (which in skate boarding means that you land all of your jumps and spins on your left foot). “It really does change the way you look at the world,” Korine said of skating during a talk at the British Film Institute in 2016. “You’re always looking at the back of buildings and alleyways and abandoned parking lots, and spending time in empty swimming pools. There’s an outsider element to it ... you’re thinking about how to do tricks that turn things on their head. It reforms your imagination.”

JUDGMENT

When critics refer to Korine as “amoral,” it is typically delivered with disdain. Exploring questions of morality without passing judgment is one of the pillars of Korine’s œuvre, how ever. In 1995, he told the Chicago Sun-Times: “I didn’t think about shocking people when I wrote [Kids]. I didn’t even think about a message. I wanted to make a movie and I wanted it to just be like you’re looking at a picture. What I hate is all of the crap that’s coming out of Hollywood right now. It’s belittling to the audience. They pound you over the head with these messages and then there’s nothing left. There’s no margin of the undefined.”

Films such as Gummo and Trash Humpers present unsavory subjects – everything from catkilling to murder – not as taboos, but as they really are: things that form the fabric of daily life in America.

“What I hate is all of the crap that’s coming out of Hollywood right now.” – Harmony Korine

Korine shines a spotlight on the people, places, and things that most folks willingly look away from, and which, in cinema, are frequently ignored. The worlds that Korine creates are populated by criminals, antiheroes, misfits, outliers, and underdogs; their misadventures speak to the harsh realities of poverty, mental illness, and disability. Although films including Gummo, Julien Donkey-Boy (which is based on an uncle of Korine’s who experienced schizophrenia), and Spring Breakers have earned him accusations of exploitation, the tenderness with which he depicts characters is frequently overlooked. Korine’s empathy is particularly on display in Mister Lonely (2007), a story about celebrity impersonators, and The Beach Bum (2019), which tells the story of seaside degenerates. Often, Korine presents crime as a form of sublimation. In a conversation about Trash Humpers for the New York Press in 2009, Korine said: “They enjoy fucking and burning, but they do it in ways that are transcendent, poetic. They take sadism to a new level, turning it into an art form.”

INTOXICANTS

Artist Mike Kelly, for a 1997 interview in Filmmaker Magazine, described Korine’s work as a “visual inebriant.” The act of consuming drugs appears frequently in such films as Gummo and The Beach Bum, the latter of which is Korine’s own take on a stoner comedy like Cheech & Chong’s 1978 Up in Smoke. But the fragmented or liquid narratives in his films also make the viewing experi ence feel like being under the influ ence of something psychotropic. Many of his paintings exhibited at Gagosian over the years – particularly the psychedelic collections in “Blockbuster” (2018), “Young Twitchy” (2019), and “Fazors” (2016) – were made with repetitive, looping motions intended to evoke the feeling of hallucination.

Drugs also played a significant role in Korine’s personal life. “I used to party with him,” photographer Ryan McGinley told New York Magazine in 2008. “Being bad with Harm back then was like shooting dope with Burroughs.” Intoxicants also made possible some of Korine’s more extreme projects. To make the unreleased film Fight Harm, Korine would pick fights with people in New York City, with the intention of being beaten up. The production resulted in multiple hospital visits and two arrests.

After the release of Julien Donkey-Boy, Korine further delved into his addictions and spent years as a drifter. In 2003, he spoke in Les Inrockuptibles about the time he spent in Paris: “I had enough strength to get out of bed and take whatever substances would help me make it through the day. And that’s about it. I felt my teeth starting to fall in my mouth and my fingertips and toes were beyond numb. I had lost my sense of smell and my sense of taste. I was dying, but it was taking too damn long.” He eventually wound up back in Nashville, where he claims to have done nothing but mow lawns for a period of time. When the desire to create returned, Korine made Mister Lonely, after an eight year hiatus from directing feature films.

FAME

Famous people have long flocked to Korine. They include actors and musicians, such as his ex girlfriend Chloë Sevigny, who starred in his early films, and friends David Blaine and Leonardo DiCaprio, who shot the footage of Fight Harm. Directors are no exception. “When I saw a piece of fried bacon fixed to the bathroom wall in Gummo, it knocked me off of my chair,” Werner Herzog told The New York Times in 1999. Herzog would go on to act in Korine’s film Julien Donkey-Boy, which was made under the tenets of the experimental filmmaking movement Dogme 95. Dogme’s cofounders, Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, are among the filmmakers who championed Korine’s early work, alongside Gus Van Sant and Jean Luc Godard.

“That’s something I never understood: motherfuckers who are just all up in their feelings.”

– Harmony Korine

Korine has always been at home in the cosmos of the rich and famous, but he also plays with the idea of celebrity in many of his films. His casting choices often create a meta discussion, in which the reputation of the actors is placed in dialogue with the film and its characters. Casting Disney stars Vanessa Hudgens and Sele a Gomez as girls gone gangster in Spring Breakers arguably operated as a conceptual artwork. “There was something intriguing about using primarily girls known from a Disney type reality ... girls of this generation that best represent a certain type of ideology,” Korine told Indiewire in 2012. Much like the way he blurs fact and fiction in his storytelling, he intentionally obscures lines between character and actor.

MAYHEM

“While I wouldn’t say the films were pure provocations ... well, some of them were pure provocations,” Korine told Kohn in 2013. One of the things that makes Harmony Korine Harmony Korine is his insatiable appetite for mayhem. Particularly in his early years, Korine was hellbent on stoking flames in whatever manner possible. In 1997, The New Yorker compared him to Rimbaud: “If we had been living in Paris in the 1870s, we would have found Arthur Rimbaud annoying – obnoxious, pretentious, self righteous, overhyped. A canny teenage combination of naif and faux naif arrives in the metropolis, declares himself a visionary, badmouths everyone, and produces perverse images that attract a fanatical following among the stylish.”

Korine made multiple films that stirred moral panics and said such things, in Dazed, as the “ bourgeois fuckers” who don’t understand or appreciate his work “must die,” but his greatest provocation may have been his decision to circumvent Hollywood altogether. After the release of Kids, agents and studios knocked on his door incessantly. Despite his refusal to pander to corporate structures and industry norms, Korine eventually in filtrated the establishment without be coming a part of it. “The most subversive thing you can do with this kind of work, the most radical kind of work, is to place it in the most commercial venue,” he said of film, during a webcast at the Toronto Film Festival in 1997.

In more recent years, Korine has continued to amuse himself by exploring aspects of “lowbrow” culture in “highbrow” circles and venues. Included among the many works shown during his 2017 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou was a series of paintings of boats with porn names, such as Ocean’s 11 1/2 Inches. Korine has compared Britney Spears tweeting about Spring Breakers to winning an Oscar, and he set the internet on fire when he stated that TikTok Radio is the best radio station that has ever existed. Given his lifelong commitment to subversion, it comes as no surprise that he is embracing the most contro versial technologies and methods of production of the present.

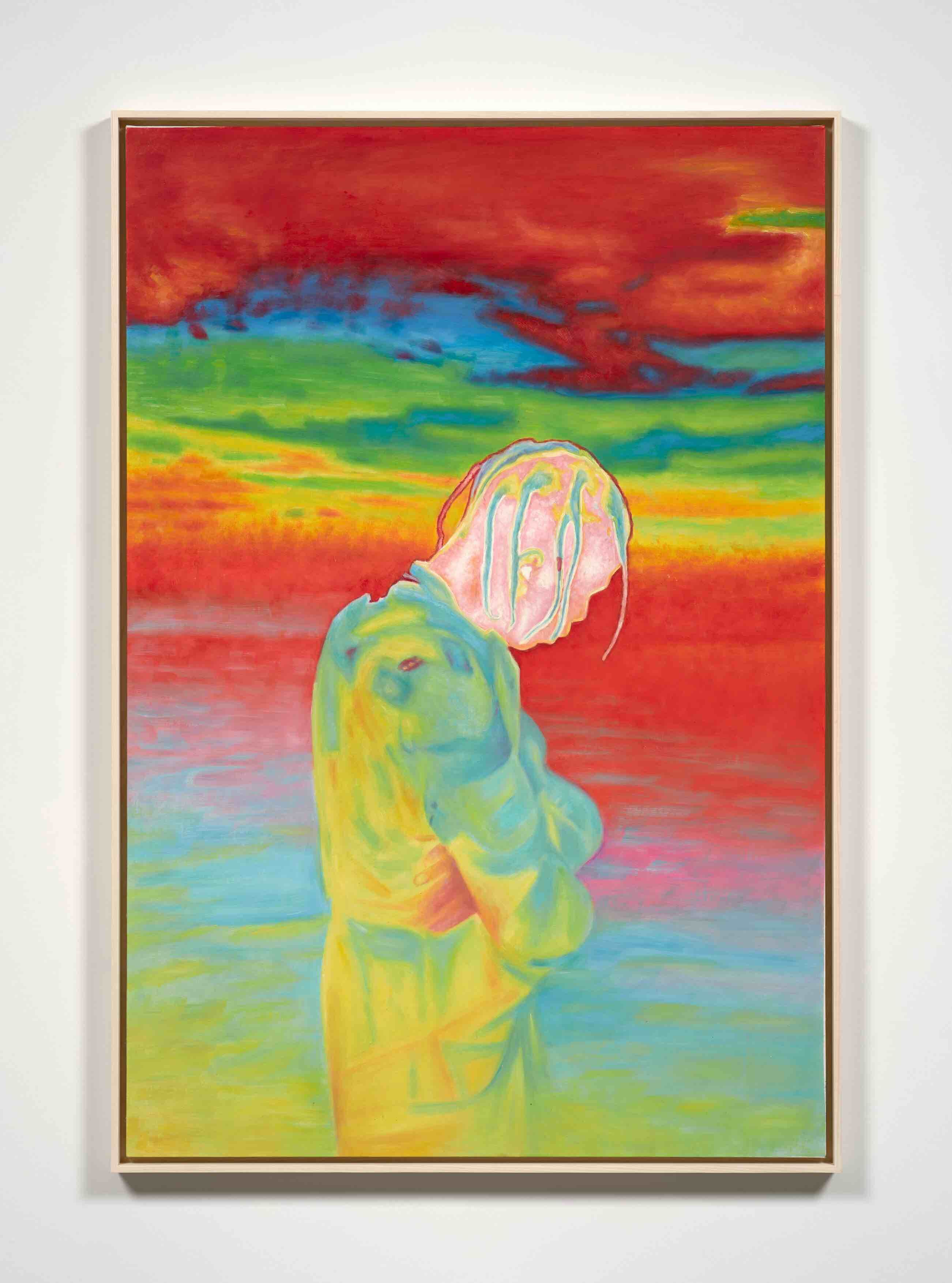

After years of representation at Gagosian, Korine held his first solo exhibition with Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles in September 2023. His show “AGGRESSIVE DR1FTER” includes Technicolored paintings based on stills from his new feature film, which was shot in infrared. The painting Zion’s Lament depicts rapper Travis Scott, who plays Zion, the protagonist’s protégé

AGGRO DR1FT

In Aggro Dr1ft, the characters’ style, physical movements, and methods of speech are designed to mimic the feeling of playing RPGs – or roleplaying video games – such as Call of Duty and Halo.

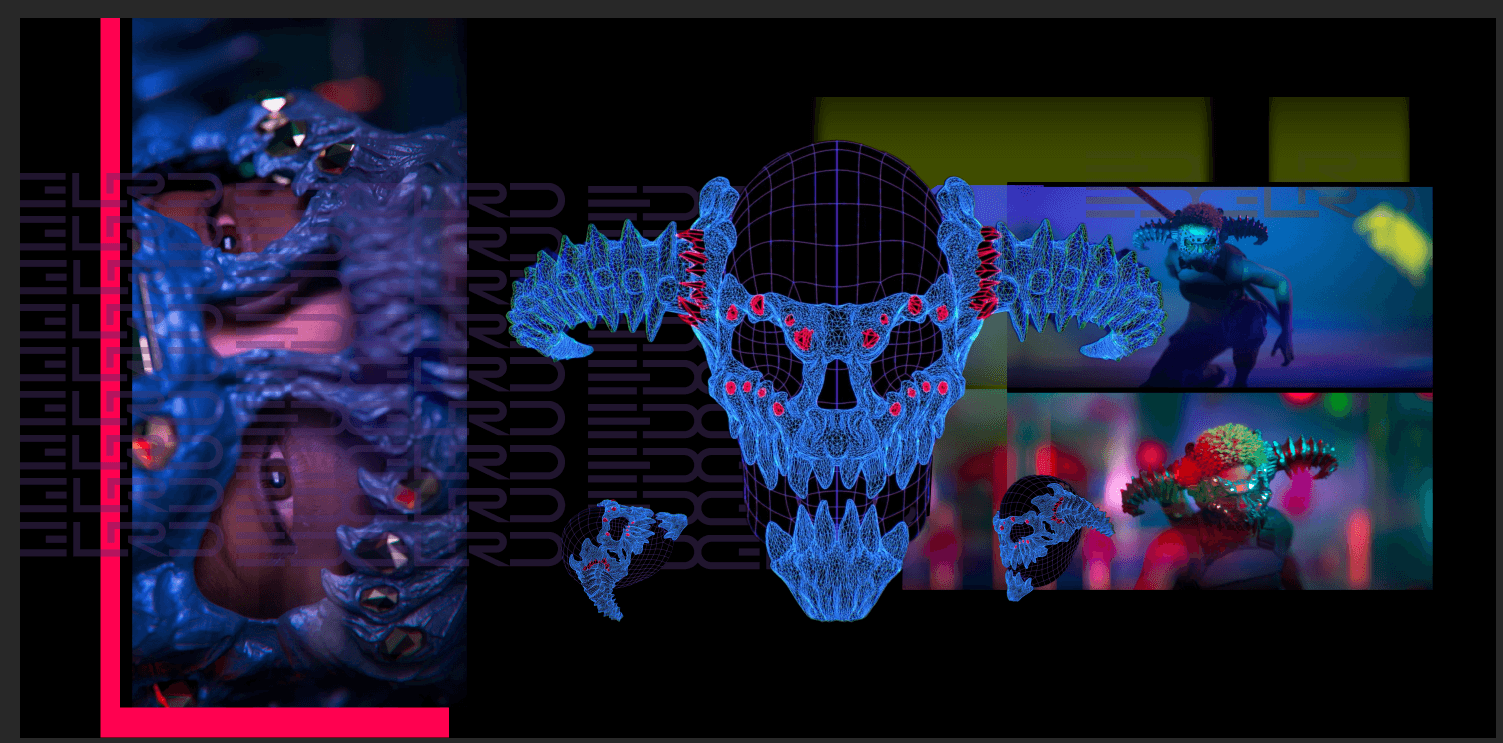

After the premiere of Harmony Korine’s Aggro Dr1ft at the Venice Film Festival, I’m ready for the standing ovation to end – it’s 2am. The director and his accompanying posse are beginning to sweat in the blinding spotlight, which is slowly roasting them alive in the row in front of me. They are no longer wearing the extravagant, horned demon masks they wore when they came in, ones based on a visual trope that reoccurs throughout the film. Teenage hypebeasts and indie art world patrons begin chanting, “Harmony! Harmony! Harmony!” for what feels like an eternity. After five full minutes of clapping, I escape the mezzanine. Variety reported the applause lasted for a total of ten minutes.

Little information about Aggro Dr1ft (2023) was made public in advance of the film’s release – apart from the fact that it stars Travis Scott and Jordi Mollà, and was produced by Korine’s new company, EDGLRD (pronounced “edgelord”). Although I hoped for the missing-vowel trend to end in the 2010s, it seems a fitting choice for Korine. The artist has long told stories with empty spaces. He has left things out of the frame. The minimal intel about the film on the festival website leaves much to the imagination:

SYNOPSIS

In the seedy domain of Miami’s criminal underbelly, a seasoned hitman embarks on the relentless pursuit of his next target. Shot entirely through thermal lens, he navigates a twisted world where violence and madness reign supreme. Tensions unravel, leading to a psychedelic journey that blurs the lines between predator and prey.

Wild days, wild nights. Wasn’t wanting to make a movie. Was wanting to make what comes after movies. Was wanting to be inside the world. More like a video game. But who’s playing who. GAMECORE. Edglrd. Something new on the horizon. Life is good. Without it we’d be dead. AGGRO DR1FT. In between worlds. Locked and loaded. An ode to the aggressive drifter.

The statement is a clever nod to the triumphs of Korine’s past, with a quote from his film Gummo – which won the top prize at this same festival 26 years ago – and his ambitions for the future, with EDGLRD. Described by his PR as Korine’s “wildest project to date,” EDGLRD is a new, “artistforward design collective” consisting of a team of creatives who specialize in new technologies. The energy in their Miami studio resembles a marriage between the Bauhaus School and a tropical tech startup. Their mission is sufficiently lofty: “To change the way art is consumed, built, interacted with, and distributed,” according to a press release. Aggro Dr1ft is the first official EDGLRD project re leased, but the team has also set out to design video games, fashion lines, and just about everything else under the sun.

No amount of briefing could have prepared me for what it felt like to watch this 80 minute “gamecore” film. Shot entirely in infrared and layered with VFX and AI, Aggro Dr1ft immerses the viewer in a Technicolored hellscape populated by guntoting militia members, air humping villains, and twerking strippers. With repetitive and contradictory monologues that mirror scenes cut from video games, as well as looping, awkward movements that mimic RPGs, Aggro Dr1ft places you in the context of gameplay but robs of you the freedom and agency you have in openworld design. Watching it was an almost out of body experience that was frustrating, amazing, and terrifying, like playing Grand Theft Auto: Vice City with VR goggles while on 15 tabs of acid.

"What the fuck did I just see?" is a thought I’ve had almost every time I’ve watched a Korine film. I thought it after I saw a dog impaled on a satellite dish in Gummo, and as a white, cornrowed drug dealer (played by James Franco) sings Britney Spears’ “Everytime” with balaclava and bikini wearing sociopaths in Spring Breakers. I thought the climax of the final fight scene in Aggro Dr1ft, in which Mollà’s character gruesomely decapitates his enemy with a knife that’s too small for the job, would be the image from this film that burned deepest into my memory. But then came the scene afterward, when little people in hoods and demon masks play with the severed head as if they were children on a playground, tossing it around while blood and brains slowly leak out. I left the theater feeling what I feel almost every time I watch a Korine film: unsure whether that was the best thing or worst thing I’ve ever seen.

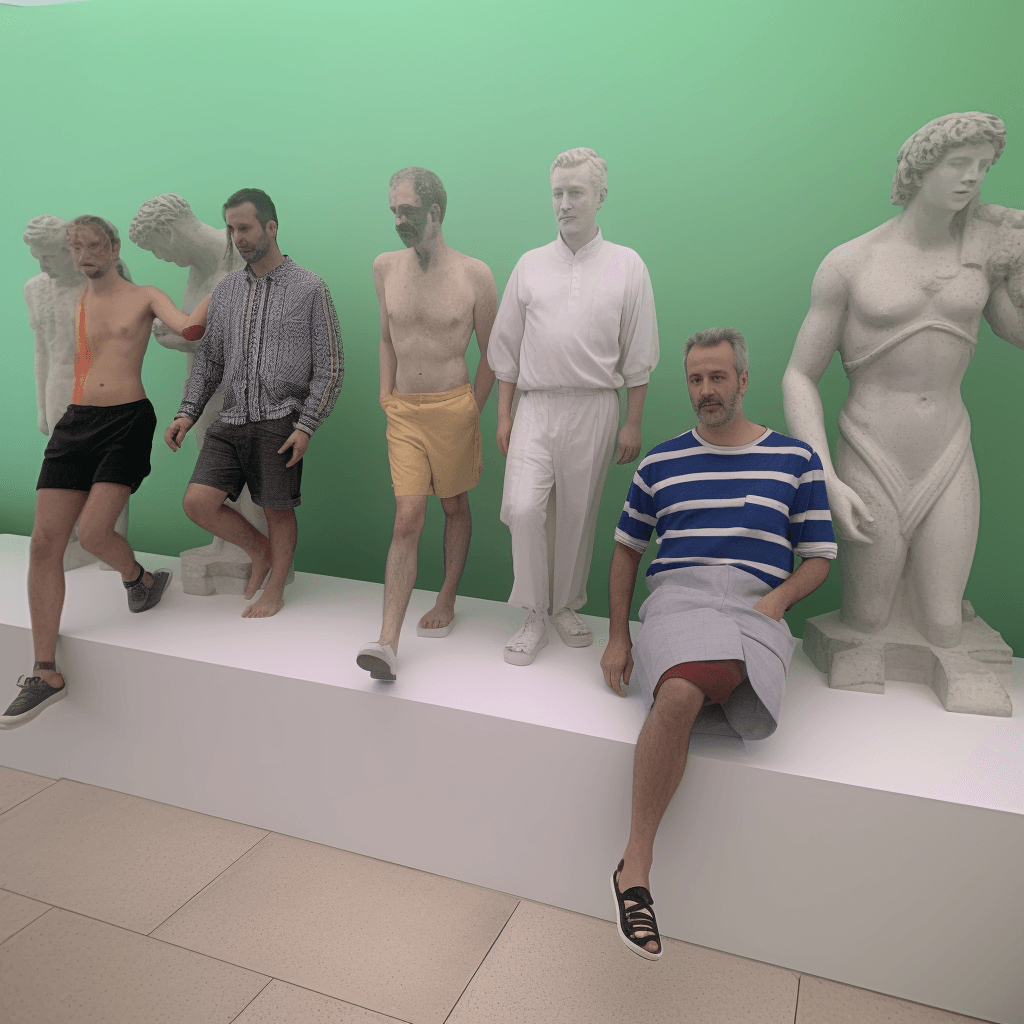

Harmony Korine (center) pictured with EDGLRD members Eric Kohn (left),

who oversees film strategy and development, and visual effects supervisor Joao Rosa (right) at the Venice Film Festival in 2023

INTERVIEW WITH KORINE PART 1

CASSIDY GEORGE: I almost didn’t recognize you without the demon mask you’ve been wearing around.

HARMONY KORINE: I would have worn it, but it’s a little heavy for an audio [interview].

CG: Some journalists on Twitter are claiming they’ve never seen more walkouts in a theater than at the Aggro Dr1ft screening.

HK: I guess it makes it the same as everything that I’ve ever done.

CG: Are there any aspects of the film that you think make it susceptible to walkouts?

HK: No. It seems like it would just be fun for everyone. It’s just an hour and a half. There’s the whole history of everything else and then there’s [Aggro Dr1ft]. Why wouldn’t you want to experience it?

CG: You’re not striving to make something that incites extreme reactions?

HK: I wasn’t setting out to do “this” or “that,” but I did want the film to be, in some ways, an attack on the senses. It’s strange: it seems to affect people really differently, based on the viewer.

It’s difficult to articulate what I was trying to find. It was more about a feeling, a feeling that has some kind of physical component to it. I am always trying to get to a point where the experience is more sensory and beyond a simple kind of articulation. Like the feeling of being in a club or a rave, where the images really pummel you. I’ve always loved films that induce a kind of hypnosis or trance-like effect.

CG: Were you ever a raver? I know you also love electronic music.

HK: I went to a few crazy ones in New York in the 90s and had a lot of fun, but I was never, like, a full raver.

CG: So, it was more about translating a similar kind of immersive, audiovisual experience into film?

HK: In the beginning, we didn’t even approach it as a film. I was just toying around with the idea of what a film could be. I’m trying to get excited by the medium again. How can we utilize tech in a way that’s different, in a way that we haven’t seen before? We weren’t trying to make the biggest film in the world. Ultimately, I am really just trying to entertain myself.

To do that, I put together a group of creative people – tech kids, VFX and AI people, game developers, my cinematographer, and designers – and said, “Let’s experiment and try and create something that feels new and immersive.” How can we tap into the idea of aesthetic drugs? It’s essentially a lab. Everybody worked together to design the way the film looks and feels.

CG: It sounds like Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory.

HK: It’s a little bit like that, yeah! It’s closer to a design collective. We design everything, from a feature [film] to a skateboard, game, or pair of socks. They all play off each other.

CG: In a talk at the BFI in 2016, you said, “Art is a singular vision” and that “the whole idea of socialized … creative environments is terrible” and has “killed a lot of art.” Isn’t that what EDGLRD is all about? What changed for you?

HK: The way that we’re communicating is changing. For the first time, it feels like tech is advancing in parallel steps with human creativity. The EDGLRD lab is a place where we can really test the limits of that.

CG: This love of video games – is that a recent development?

HK: I grew up with games on Nintendo. My kids are always on Twitch, so I slowly started to get into it. First, it’s Pokémon Go, and then you get into The Legend of Zelda, and the next thing you know, you’re deep in World of Warcraft! It was a natural [progression].

CG: Aggro Dr1ft is your goriest film to date. Did the filters of the infrared camera, VFX, and AI allow you to explore … violence with more freedom?

HK: Oh, definitely. It was great to unleash that, creatively. Video games, horror, and hip-hop are really the only things that allow for transgression anymore. That’s why, in a lot of ways, they’re the only genres that matter. You can still experiment within those forms.

CG: Do you think the gaming world is less hung up on questions of ethics and the importance of “messaging” than the film world [is]?

HK: I think that the world of gaming excels because of that. It lets people get it out, have fun, and not feel guilt. The film world is just completely fucked.

CG: Do you think feature films will become obsolete in the near or semi-near future?

HK: I don’t think they’ll be obsolete. I think older, linear, narrative films will age out and be replaced by something else. The length and the way people watch them will change. I think audiences will want a more immersive experience.

CG: What was your thinking behind casting Travis Scott in Aggro Dr1ft?

HK: It was kind of a no-brainer. Travis and I have worked together before – we shot part of his film Circus Maximus earlier this summer – and I think he is doing big things within this culture. I like that everything he does is so vibe-based and moody. The energy around him just made sense for the film and the character.

CG: Do you think platforms like TikTok have made culture at large more appreciative of “vibes”?

HK: Probably, yeah. You could make the argument that everything now is post-meaning. All of culture – literature, poetry – the meaning of it has been obliterated. Attention spans have been destroyed. The way people are processing things … I mean, you could even get into transhumanism. What even are we, at this point? Is there anything that means anything, beyond just the vibe? When you boil everything down, it’s just about what’s “based.” Like … how based is it? There’s nothing else.

CG: You’ve always had a short attention span and been a big believer in vibe supremacy. In making films that catered to those things, like Gummo, you were going against the grain. How does it feel now that people and the media landscape are on your wavelength?

HK: It’s rewarding! It’s interesting. I always felt like culture would catch up at some point. And yes, so much of what I have done is just a product of my own attention span and my inability to sustain prolonged thought. Gummo is really just fragments and clips.

At the same time, even with this movie, everything is so divisive. People always try to make you feel bad for experimenting. Every time I come out with a new film, I feel like the kid in school whom the teacher is slapping on the wrist. You always feel like you’re being scolded by your parents. I probably just like that, though! [laughs] If it didn’t feel that way, maybe I’d feel like I did something wrong.

CG: Is action more important than emotion?

HK: I think emotion is good. You always want people to feel something, but there’s a limit. You also don’t want people who are just all up in their feelings, all day. That’s something I never understood: motherfuckers who are just all up in their feelings.

CG: No meaning, some emotion, all action … that sounds a lot like a video game.

HK: That’s also why I like WorldStar so much!

CG: It’s very “based.”

HK: To me, it’s, like … the core, the source.

CG: Violence is an ongoing theme in your work. Why do you think you’re so drawn to it?

HK: It’s mostly a primal thing. It’s a subject matter that’s always there for me, because there are so many different ways to explore it.

CG: You also have this adjacency to the hip-hop world. Is that a bridge, perhaps?

HK: Do you mean because there’s violence in hip-hop?

CG: Or just an understanding of it?

HK: I think a lot of it has to do with the way you grew up and the things that you saw. Rap is my favorite and has always been. I used to listen to Three 6 Mafia, Too $hort, and Project Pat as a kid on the school bus.

CG: And now you live in hip hop’s unofficial new capital.

HK: All of Florida is really interesting, but South Florida has a really heavy scene. There’s Kodak Black, there was XXX. Gucci, Future, DJ Khaled, Lil Wayne, they all live there. Then there’s the history, with Trick Daddy, 2 Live Crew, and Trina. And then all the young kids … it’s just popping! Florida’s the vibe. The Mecca.

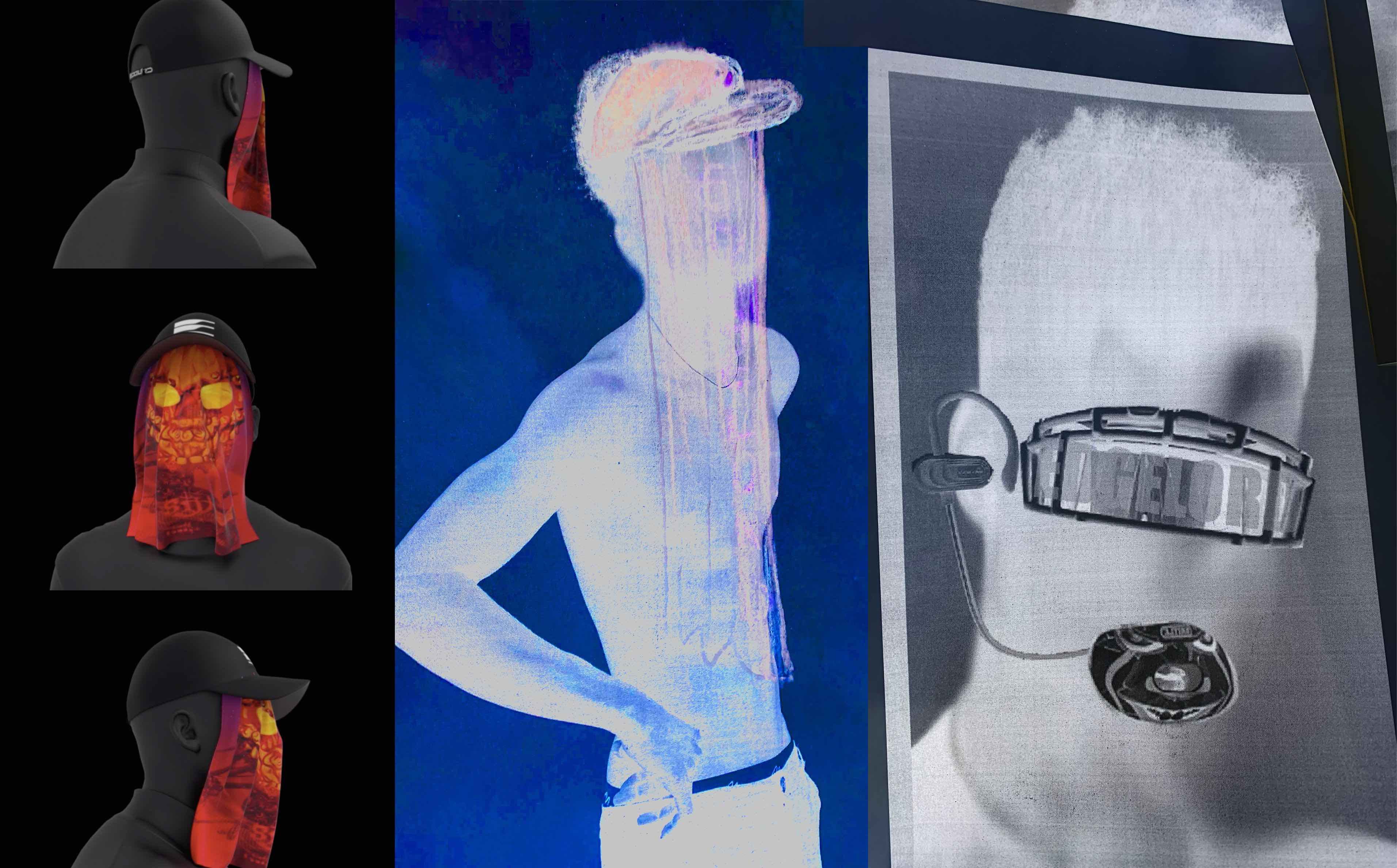

One of the ambitions of EDGLRD’s design studio is to manifest digital concepts in the physical world. EDGLRD artist Nicolau Vergueiro says of their recent prototypes and designs: “I’m calling it fashion, for lack of a better term. They’re really expressions that deal with the body”

ENTERING EDGLRD

On any given day at EDGLRD studio in Miami, there is talk of villains with baby faces who invade mansions and kill their owners. Studio-engineered terms, such as “Blinx” – a word for short, moving-image artworks – are thrown around with ease. H.R. Giger-esque mask prototypes are developing in a 3-D printer in one room while artists in cubicles experiment with Unreal Engine and Midjourney in another.

“Wanda is a hotel receptionist with alopecia. She’s also a kleptomaniac,” said EDGLRD artist, Nicolau Vergueiro. “There’s also Trinika, who immigrated to Miami from Trinidad. She’s a tech psychic and a TikTok influencer.” Wanda and Trinika are just two of 40 characters known in the studio as “FloridaLords” – each of whom has an intricate backstory and lore. The ways that these various characters will manifest in the digital and physical realms are still up for discussion. “We’re creating a web of IPs that interconnect with one another,” Vergueiro added.

Another big character in the room is Florida itself, a state of contradictions, which has undergone tremendous changes since 2020. More than 400,000 people moved to Florida between July 2021 and July 2022, and Miami has spawned its own tech-exodus. Attracted to its weather, relaxed Covid-19 restrictions, and lack of state income tax, cryptobros and venture capitalists flooded the city during the pandemic. Florida still maintains its reputation as the backward home of retirees, but Miami has doubled down on its commitment to embracing forward-facing technologies – earning it the unofficial nickname “Silicon Valley of the South.” In 2021, Bitcoin ATMs popped up all over Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood, and the mayor announced that the city would accept tax payments in crypto. Although “going full Bitcoin” (as the city was described by The New York Times in 2021) has proved to be a dodgy bet, many tech investors have shifted their focus away from such buzzwords as blockchain and NFT, and toward a new fixation: AI.

Joao Rosa, a VFX artist turned EDGLRD overlord, has helped recruit and relocate 12 artists to Miami to join the collective this year. “I was given the green light to get the best of the best,” Rosa told me. Before working on Aggro Dr1ft, Rosa did VFX for Marvel films and helped create title sequences for such TV shows as Game of Thrones. He was the first artist to officially join Korine’s new company. With what appears to be plentiful financial backing from Matt Holt, a growth investor who also happens to be on the board of the Paris Review, EDGLRD is in an idyllic situation. “You can easily get overwhelmed with options,” Rosa said of staffing the collective. “The willingness to move to Miami is a filter. Willingness to work with AI is another.”

Korine’s shift in focus to various nerdy pursuits – CGI, VFX, AI, 3-D, VR, gaming – may seem like a curious career pivot for anyone who knows him as the raw, gritty skater who shot a film on VHS about people who hump trash. But for an artist whose brain is constantly bombarded by images, scenes, and characters, being surrounded by a team of tech experts who have the power to turn those ideas into assets within days, minutes, or even seconds is like having creative superpowers. Disney headquarters may be just a few hours away in Orlando, but for Korine, Miami is the place where he can explore worlds and “make dreams come true.”

Lizzard is one of many characters comprising EDGLRD’s “FloridaLords,” a series of eccentric Floridians with overlapping narratives. “It’s a mixture of Marvel superheroes with the Garbage Pail Kids,” Vergueiro says

INTERVIEW JOAO ROSA

CASSIDY GEORGE: Were you bored with the work you were doing before Aggro Dr1ft?

JOAO ROSA: I was never bored because I love what I do. But the process of making Aggro Dr1ft felt entirely different. If you’re contributing to VFX and animation professionally – and especially if you are working on mainstream films – you’re not really a part of the creative process. That’s where EDGLRD changes everything. For everyone working in this industry, it always seemed like such a missed opportunity. The people who work with these tools know their possibilities and yet are constantly given direction from people who have no knowledge of them, and therefore no knowledge of what’s possible. EDGLRD understands that, and that the tools used to make games, visual effects, animation, and architecture are converging into one.

CG: Are you a self-taught artist?

JR: In this field, you have to be a person who can self-teach; otherwise, you’re going to become obsolete. Right now, the hardware is becoming so powerful that real-time engines are taking over. That’s a big revolution. A lot of companies are attached to the old way of rendering things, because they have done it that way for decades, and have built a pipeline around that. EDGLRD is embracing new workflows.

CG: It seems like a field that is constantly presenting existential questions.

JR: As animators, we have always been conscious, even before AI, that we are constantly building the tools to replace us. It’s just the norm. If you work for a big company, you’re creating tools that make current tools work faster. For example, a senior artist will create a tool for an animated character to breathe fire. Then, a junior artist will implement that tool. Nowadays, it goes beyond that. They outsource that labor of implementation to other countries, for even cheaper. AI has just made the realities of our work more explicit. We were working like robots before, which is what makes us easily replaced.

When Harmony approached me to start EDGLRD and build the team, I understood the importance of bringing fine artists into the mix. Fine artists have always dealt with existential questions like: Is my work good enough? Could this have been made by a machine? Could this have been made by a child? I find they are much quicker to embrace these tools, because they’re excited about the future, compared with people from the animation community, who are scared they may lose their jobs. The reality is the opposite. AI has made us realize how badly we need artists.

CG: What else is EDGLRD doing differently?

JR: Structure, pipeline, hierarchy – these are things that we are softening. I’m trying to shape the culture of the office, based on my previous experiences. Most importantly, a company where I worked at for many years called Elastic. Artists were there to work but also had their own lives. It didn’t feel like a frat house or a family. I’m not into that “family” vibe. I am into small teams that are very efficient. Offices with bean bags and snacks … they’re doing those things to distract from the fact that the work is soulless. It may be disappointing to some people, but EDGLRD is all about the work. There are no snacks here and no chairs that hang from the ceiling – because what we are doing is actually fulfilling.

CG: EDGLRD’s investor is Matt Holt. Based on the freedom you all have, money doesn’t seem to be an issue.

JR: We are in a privileged position, in that we have an investor who is interested in letting us stay a independent at this stage because he believes so passionately in what we’re doing. Finances are not a part of my day-to-day work, but from my perspective, Harmony is a filmmaker who is uniquely entrepreneurial, opening up different types of revenue streams around his creations. The [level of the] people and companies that approach us – Kim Kardashian, Gucci, Travis Scott, Marc Jacobs – are exciting.

Generally, we avoid doing commercial things, because we’re focused on our own IPs and developing Harmony’s creations, but if we ever want to do something more commercial, it’s always within our reach. It’s not difficult for us to fund our endeavors.

CG: The Aggro Dr1ft experience is more like playing a video game than watching a film. Did certain games serve as inspiration?

JR: In terms of design, yes – especially with the demon [character]. In terms of narrative, I’m much more inspired by film. Many people on the team are more connected to video games and anime, though, so there are a lot of elements mixed in. The movements, the way that interactions happen, but also the dialogues and monologues, that all takes me to game [territory].

I have seen Aggro Dr1ft more times than anybody, and the thing I grow more and more attached to in the film is the text. I also think it’s the thing that people most easily ignore because the film is so visually stimulating. The assassin’s thoughts, which are often rambling and contradictory, feel very genuine and human to me. He says, “I’m the world’s greatest assassin.” And in the same phrase, “I’m the humble assassin.” My favorite reviews of the films so far are the ones that, regardless of if they’re praising it or criticizing it, recognize that it’s an honest film. It’s real. The writing is where a lot of that comes through.

CG: What do you think about the reviews thus far?

JR: You know, I thought it was a myth when people said Harmony doesn’t care about reviews. But it’s absolutely true. The negative ones are the ones he finds the funniest. He’s been doing this since he was a teenager, so he’s used to it. I’m more attached to what people think of what I do, but it’s awesome to be around people who aren’t. It’s freeing.

Harmony is not making things with people our age in mind. He’s interested in younger audiences. When I look back at his work, it always predicts where culture is going. Aggro Dr1ft is more experimental than any of his previous films were, but people should pay close attention, based on his past record. All of the reviews so far seem to acknowledge that this is the first film in decades that proposes something new.

CG: It felt wrong to watch something that represents “the future of entertainment” in an old, grand movie theater in Venice. Have you all also been discussing the future of screenings and exhibition spaces?

JR: That’s a difficult one! As far as exhibiting the work, the goal from day one has been to make something that feels different. All the things we want to do – have the freedom to create and explore worlds, and so on – I’ve seen [them] in VR. But VR technology, for some reason, is just not widely embraceable yet.

CG: Remember that 3-D movie craze in the 2000s? So many people were convinced that in the future, all movies would be in 3-D. VR hype reminds me of that.

JR: If the pandemic wasn’t enough to make VR a thing, I don’t know what can. But I do think VR is going to grow more and more popular. We’re also interested in creating immersive experiences without the mediation. 3-D films are mediated by glasses, and VR is mediated by goggles. Is it possible to not have those things? That’s something we ask each other.

Images from an AI-generated concept deck, created using Midjourney. The characters depicted are not actual members of EDGLRD but are based on an amalgamation of portraits of the team. “None of us were really there. You can pick up where AI got some of the features from us, but AI is really creating a different kind of physiognomy altogether,” says Vergueiro

INTERVIEW NICOLAU VERGUEIRO

CASSIDY GEORGE: What is your earliest memory of Harmony’s work?

NICOLAU VERGUEIRO: I was a teenager in the 90s. I actually saw his movies in the theater [while I was] growing up. Watching Gummo was a marker in my coming of age in Los Angeles [during] the 90s. I still remember scenes from it vividly and refer to those within EDGLRD now.

CG: What was the EDGLRD elevator pitch?

NV: When Joao approached me about EDGLRD, he said, “Harmony is putting together a new art-design collective that is interested in gamecore concepts.” I thought it was interesting but very abstract. After I watched Aggro Dr1ft and spoke to Harmony, I realized they were also very interested in designing high-concept fashion ideas and adding someone to the team who can look at everything from an artist-slash-atelier point of view. Now, I am exploring some of the EDGLRD narratives and production themes through the design of tactile objects and character development.

CG: Do you have a title?

NV: I’m a creative director but I also see myself as the in-house [fine] artist.

CG: And you were immediately open to relocating to Miami?

NV: I’m at my six-month mark now, and I can say it’s been a surreal experience. The ocean was the welcome postcard to me. I actually swim in the ocean every single day and do my laps [while] looking at turtles and stingrays. It’s making me almost believe in God.

I have to say it’s exciting to be doing what we’re doing in a weird hub. If we were in New York, it would be more traditional, in a way. We are building our own context, rather than submitting to structures that already exist or subscribing to larger, overarching cultural things. We’re piercing through that. There are also so many different interactions … you can have here that are unexpected. The radical things we are doing in the studio [are] against the backdrop of this right-wing, free-enterprise society, against our access to this wild nature.

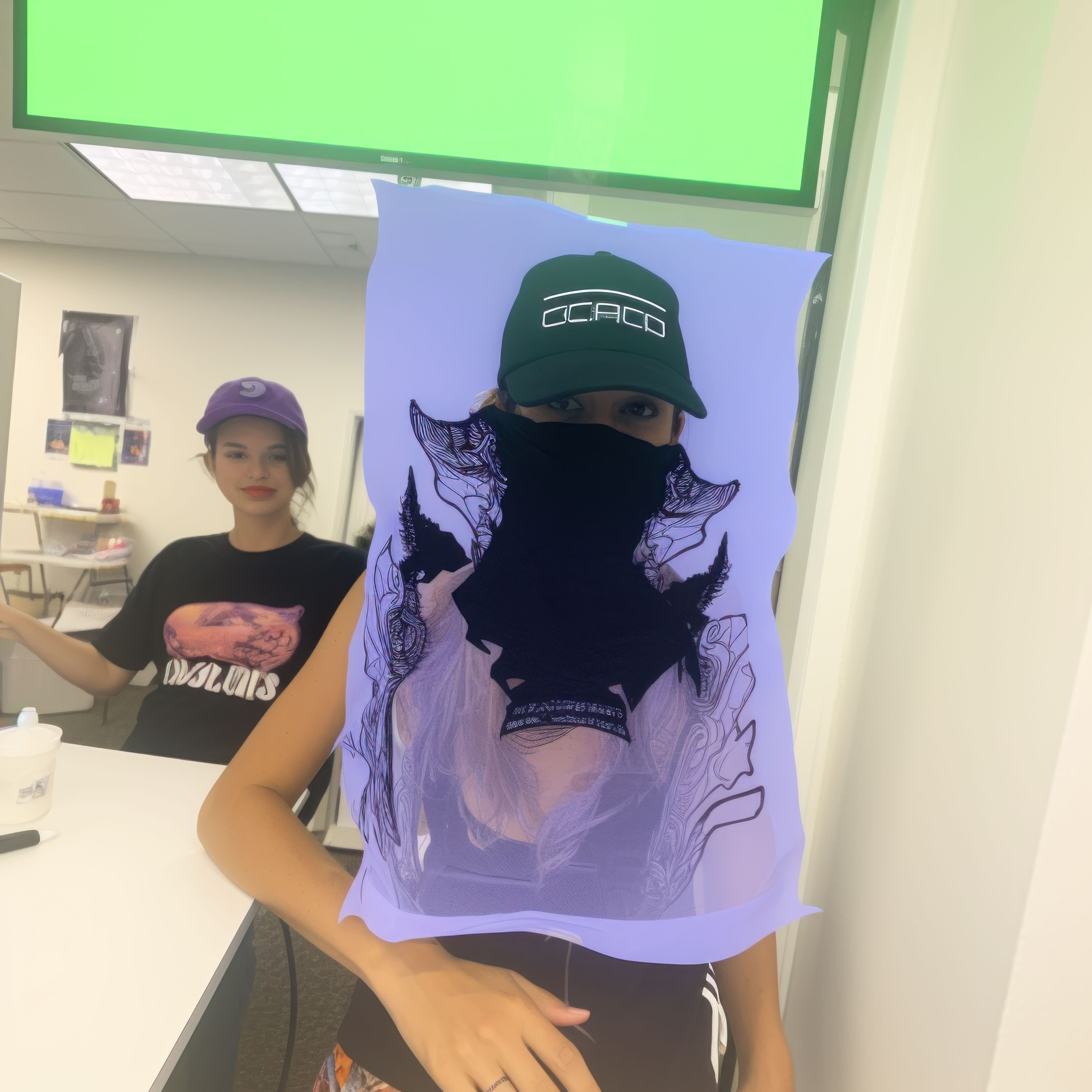

The EDGLRD team in their Miami studio, wearing demon masks that were designed in-house

CG: What are the key themes that link the EDGLRD projects?

NV: That’s the million-dollar question! There are definitely overarching ideas that Harmony had from the get-go, like “gamecore” and “Blinx.” While Blinx are moving image expressions, I have started to understand “gamecore” as a means of production. We use AI, real-time game engines, and 3-D modeling technology to create not just games or movies, but actual concepts. The 3-D aspect of things has really shifted my way of thinking and shifted how we tell stories. We look at the scope of scenes differently now, often from multiple first-person vantage points.

From day one, Harmony said, “We are not looking at any traditional structures, rules, or codes – or, really, how things have been made up until now.” Understanding this new means of production is the innovation. I keep thinking of this corny word, “pioneering.” The characters we are working with are pioneering new ways of taking agency over their lives, and we are pioneering new ways to create high concepts with programs [such as] Stable Diffusion, Unreal, Houdini … and then translating those into the physical world.

CG: How would you describe the culture of the collective?

NV: It’s very explosive. Creative sparks are flying all the time. There is a group dynamic that is very near and dear, but I am curious how that will shift, because we are growing very rapidly. There is a grassroots, homegrown feel to it, which contrasts with the high technology we have access to and [with] the expertise of the artists here.

CG: You also have a tactile artist practice. Have you always been interested in experimenting with new technologies, or is this unique to your EDGLRD chapter?

NV: I have a very traditional, hands-on-paper-for-hundreds-of-hours type of artistic practice, but also make videos, perfromances, and collaborate works. Material culture, technology, and what it means to generate images through digital means and interfaces have always interested me.

In the past few years, I’ve explored how illustrations can be used to convey propaganda or tell stories, and I’ve also been developing my own writing practice. Both of those things [put] me in a good position to deal with the AI world and create prompts to get what I want.

It’s been really interesting to see how AI can be used to generate images and stories, but also as a tool to mesh those two worlds. All of the “FloridaLords” characters have been fleshed out through AI. Sometimes, when I enter an entire backstory as a prompt, it spits out incredible things. It was actually ChatGPT that clued me in to the fact that the character Wanda is a kleptomaniac. I was, like, “Of course she is!”

In this AI world, new advancements are constantly coming out. We are learning it while it’s being built. When Midjourney released the “blend” feature a sometime ago, which allows you to put two images together to create something new, it created alter egos for some of these characters. After seeing these images, I was then able to go back to the writing board and expand on how they became who they are. This kind of artistic process is completely new, and I find that very exciting.

Baby Invasion is a feature film about home invaders, shot from a first-person shooter perspective. The footage was created using six body cams (one worn by Harmony Korine). In post-production, the invaders’ faces have been treated with AI technology so that they appear to be babies

CG: What do you think of AI doomerism?

NV: AI reinforces how creative I am. It makes me more powerful. Ain’t no machine gonna get in here [points to his head]! I think the concern that many technicians have about losing their livelihood is more of a political query. Instead of things [such as] technical school, education should focus more on what we have that is most precious, which is our creative soul.

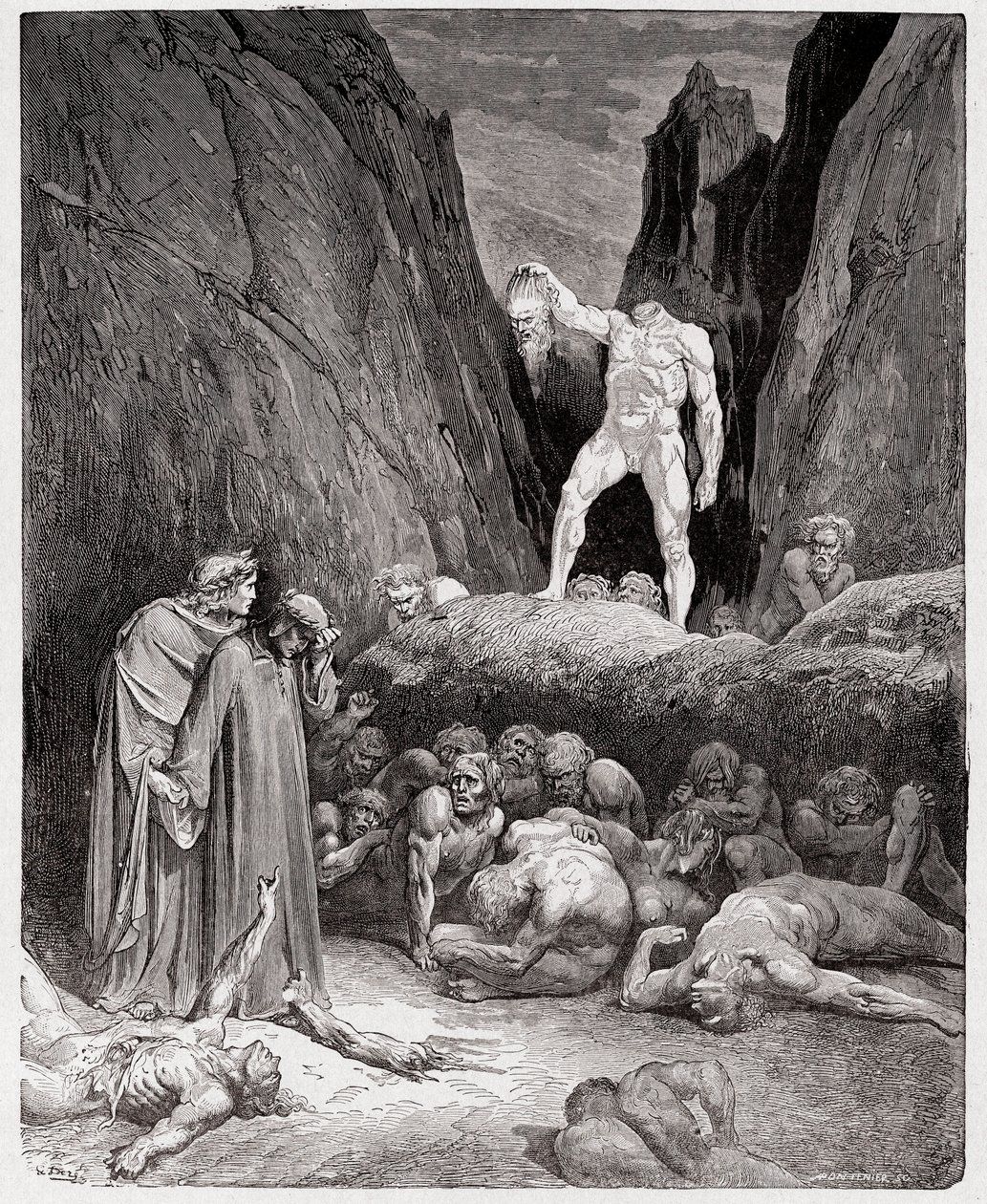

I’m also very interested in the ontological questions that AI presents. Characters that I am creating with AI, characters that are staring me straight in the eye, that I am learning and growing with … what does it mean for them to exist? What does it mean to construct these bodies? I’ve been thinking a lot about philosophical and historical texts, [including ones inspired by the figure of] Faustus and [by the] Prometheus [myth]. I’ve also been interested in alternative understandings of the origin of the earth – for example, those of the Yanomami tribes in Brazil or the Cherokee. Often, creation – of life – is embodies and narrated through technology – be it fire or the weave of a basket. What we’re doing here is a bit like that – riding a new syntax to arrive at new forms.

CG: I can imagine that, in a lab-like environment like this, where everyone is egging each other on to explore certain concepts, it’s easy to go deep – and maybe even get lost?

NV: It’s super-magical. But we don’t just hover in this abstract space. Harmony’s vision has always been about finding the banal, terrestrial, or even crass things that encapsulate it all. Yesterday Joao and I were talking about creation theory, and then we were, like, “Oh my god! Let’s just make a hologram of a humping dog!” Harmony’s curiosity about humans and their peculiarity … it’s really about bringing things back to carnal things that pierce through it all.

For EDGLRD’s Skims swimwear campaign, Korine’s only instruction to Rosa was to “push it as far as you can.” Using a combination of digital painting techniques and AI, the models’ heads were augmented with alien features. “The campaign came out during this big alien moment in the US news cycle, but we shot it months before that, which speaks to Harmony’s ability to capture the zeitgeist,” Rosa says

INTERVIEW WITH KORINE PART 2

CASSIDY GEORGE: Do you distinguish at all between the concepts of art and entertainment?

HARMONY KORINE: Not really. I always felt it was all the same thing. I don’t even distinguish between the forms. That’s what I was trying to do with [Aggro Dr1ft], by playing with this idea of singularity. Art, music, and live-action gaming all start to synthesize and become one, in a unified aesthetic. At the end of the day, anything that has an effect on you is a form of entertainment, even [fine] art. If it wasn’t, why would you come back to it?

CG: In an interview with Slant, you said that embracing criminal mentality is advantageous for directors. Can you expand on that?

HK: What I meant is that it’s mostly just an alternative way of thinking about the process and achieving what you need to achieve as an artist. It’s about figuring out ways to pick locks.

CG: With EDGLRD, you’re making work that you can share directly with consumers. Would you say that’s “picking a lock?”

HK: I hope so! That’s the point. The idea is that we’ll be able to create an infrastructure that allows us to circumvent those built-in restraints and circumvent old-school gatekeeping.

CG: Now that you’ve embraced this collaborative ethos and built your own creative militia, are you feeling more fulfilled?

HK: I’m mostly just feeling excited! It feels like the death of one thing and the birth of another. All of a sudden, we are on the precipice of being limitless. Technology has finally advanced enough where it can begin to match our level of imagination. It’s exciting to be working in a lab that is working within – but also helping create – new tech that no one has ever seen before, and we’re developing [it] in real time.

CG: Does working with so many screens and programs all the time ever feel soulless? What do you do to stay grounded?

HK: No, because all of these things are just tools. It’s about how you use them. How can we use them to make something that is hyperreal or hypermagical? How can we use them to induce something [sensory in a way that makes] you feel like you’re living inside of it?

CG: What do you do to disconnect, then? What reminds you that you’re human?

HK: I will say that’s one of the most difficult things. I have little kids. I live close to the ocean, so I go fishing. I smoke cigars, drink Cuban coffee, and walk on the beach. I take my little boat out, drink Mountain Dew, and eat Oreo cookies. I catch grouper. I cut off that way – [and by] staring at the water.

Harmony Korine skateboarding in Miami. “I still watch skate videos every day and keep up with all of the skaters,” Korine says of the role skateboarding still plays in his life. The oceanside metropolis that Korine calls home has proven to be both a fertile breeding ground for creativity and a means to escape a technology-driven process

CG: Setting out to imagineer the future of entertainment? Deciding what comes after movies? These are pretty big burdens to carry on your shoulders.

HK: I know! I try not to always think about it in those terms, because it’s so big and daunting. There’s still a kind of playfulness to it all. If it’s not enjoyable on some level, then it’s difficult to make it through. But if you aren’t asking yourself what else is out there … I mean, what else is there to do?

CG: Looking back on your career, and knowing what you know now, would you do anything differently? Are you at peace with your decisions, your path, and your timeline?

HK: No. I probably would have gone into, like … real estate. Or tried to sell Ferraris. Maybe start a lawn service. I’d do something like that.

CG: I think you would make a good car salesman. Getting funding for feature films is a lot like selling Ferraris.

HK: Yeah! I like cars. I like the way they smell. I also think I would have been a good announcer for the WWF.

CG: Whose opinion, if anyone’s, matters to you?

HK: My wife, Rachel – her opinion matters. I have a rabbi that I talk to [who’s] a weightlifter – his opinion matters. Who else? Hmm … a couple of the guys I go fishing with. That’s about it.

CG: Are you and Werner Herzog still close? Has he seen Aggro Dr1ft?

HK: I just wrote him the other day! I told him I want him to see the film. I’m really curious about what he’ll say about it.

CG: In the 90s, you were known for reciting passages from Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations from memory. Do you have a favorite?

HK: “Art is like fire, it is born out of what it consumes.”

As a physical manifestation of a character from Aggro Dr1ft, the demon mask is also EDGLRD’s first product drop. “In a more allegorical sense, the beast is kind of our mascot, because it’s the first icon that we created [which] is both a digital and physical asset, thanks to 3D printing.” Vergueiro describes it as “a living filter that delineates [EDGLRD’s] aesthetic in the real world” and “part of the mythos that we’re building”

CASSIDY GEORGE:

Write a screenplay for a Harmony Korine film which stars Harmony Korine as himself – a director who starts a design collective of artists in Miami, who are experimenting with new technologies to create new forms of entertainment.

CHATGPT:

HARMONY'S MIAMI VISION

Genre: Dramedy/Biographical

LOGLINE:

In a surreal exploration of his own creative journey, director Harmony Korine plays himself as he forms an eccentric design collective in Miami. Obsessed with pioneering new forms of entertainment through technology, they embark on a daring adventure that blurs the line between art and life.

---

INT. MIAMI ART GALLERY - NIGHT

The camera glides through an avant-garde art gallery in Miami, showcasing a retrospective of Harmony Korine’s eclectic career. Visitors are entranced by the strange and surreal worlds he has created on film.

HARMONY (V.O.)

Art is no longer confined to canvas or celluloid. The future of entertainment lies in our hands!

INT. MIAMI PENTHOUSE - NIGHT

Harmony, late 40s, a visionary director known for his boundary-pushing work, watches his own films on a projector. He’s craving something new, something that defies convention.

HARMONY

I’ve pushed boundaries … now, it’s time to break them.

EXT. MIAMI STREET - NIGHT

Harmony strolls through the neon-lit streets of Miami, soaking in the vibrant atmosphere that fuels his creativity.

HARMONY (V.O.)

Miami is a playground; technology, the tool.

INT. ABANDONED WAREHOUSE - NIGHT

Harmony recruits an eclectic group of artists, each with their own unique talents and quirks:

LUCIA

a brilliant coder with a fascination for augmented reality

DIEGO

a virtual reality artist who thrives on mind-bending experiences

VICTORIA

a neuroscientist intrigued by the merging of human consciousness with machines

RAJ

a boundary-pushing sound designer and inventor

ALEX

a young prodigy with an obsession for immersive storytelling

Together, they form an unconventional collective determined to create groundbreaking entertainment.

HARMONY

We’re not just artists; we’re pioneers.

INT. AUGMENTED REALITY LAB - DAY

Lucia, Diego, and Harmony experiment with AR, creating immersive, interactive narratives that blur the boundaries between the real and surreal.

DIEGO

(enthusiastic)

This is storytelling redefined!

INT. NEURAL INTERFACE TEST ROOM - NIGHT

Victoria conducts experiments on herself, diving deep into the uncharted territory of shared dreams and collective consciousness.

VICTORIA

(whispering) We’re becoming one with the machine. We’re becoming one with

INT. SOUNDSCAPE WORKSHOP - NIGHT

Raj orchestrates a mesmerizing sonic performance that transcends the limits of music and reality.

RAJ

Music is the pulse of our vision.

INT. IMMERSIVE STORYTELLING SPACE - NIGHT

Alex and Harmony collaborate on a mind-bending immersive experience that takes the audience on a journey through the depths of the human psyche.

ALEX

(awestruck)

We’re architects of dreams.

EXT. MIAMI BEACH - SUNRISE

The collective watches the sunrise over the ocean, their creative journey far from over.

HARMONY

Miami is our canvas, technology our brush, and dreams our masterpiece.

FADE OUT.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George

Related Content

The Weeknd Interviews Abel Tesfaye

HARMONY KORINE interviews DAVID OSTROWSKI for Ich bin gekommen um dir zu sagen dass ich gehe

I STILL LIKE TO MOW IT ALL DOWN: Harmony Korine

What is AI? Matteo Pasquinelli

“Supreme New York” by SUPREME

032c Issue #44 “EDGLRD” Winter 2023/24

MARK GONZALES: Non Stop Poetry

Special Commission for 032c by DAVID OSTROWSKI

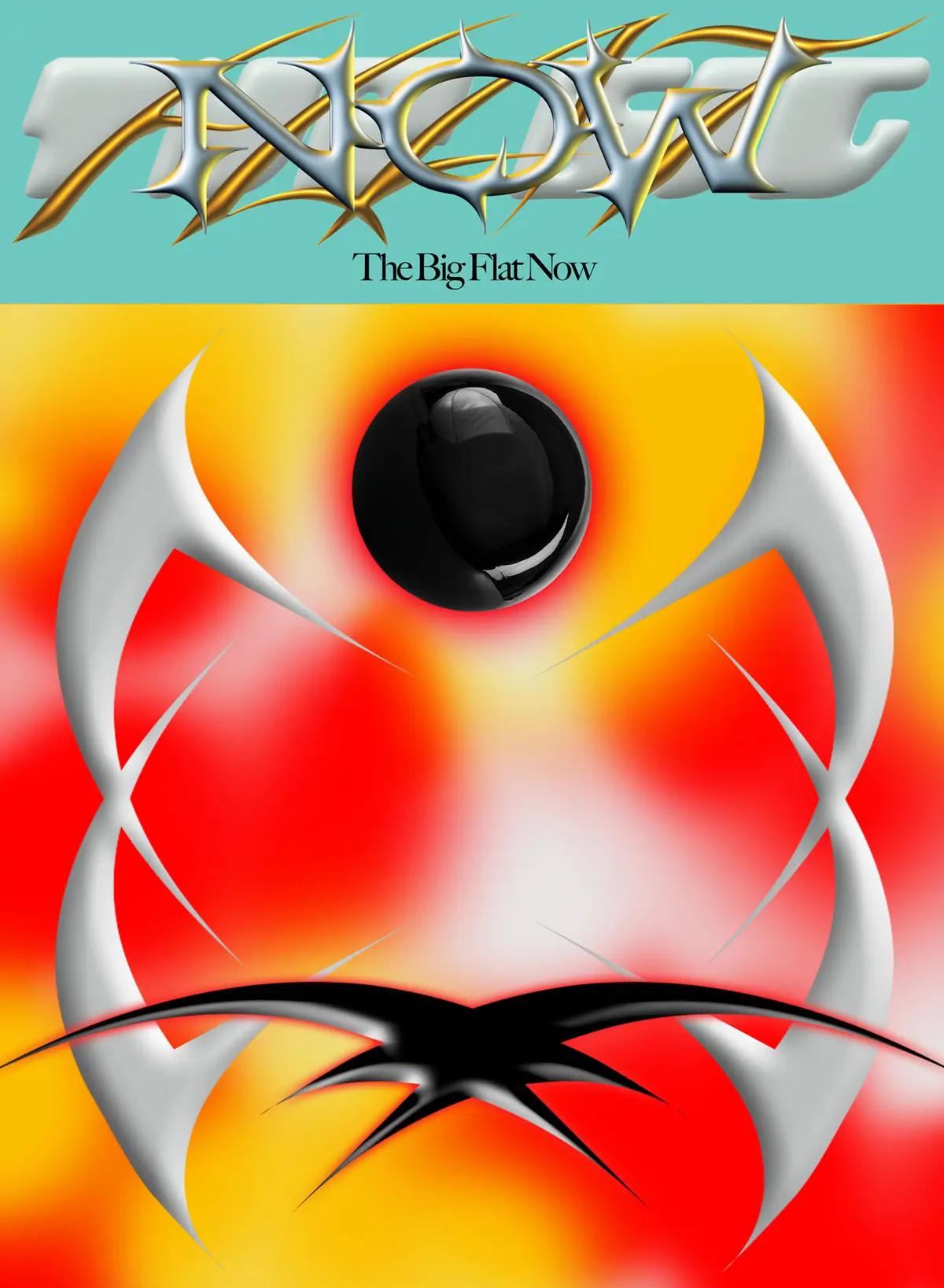

We regret to inform you that there is no future. Nor is there a past. Music, art, technology, pop culture, and fashion have evaporated as well. There is only one thing left: THE BIG FLAT NOW.

Abusing Technology with Kim Gordon

Primal Beauty Advanced Technology