Rave, Relic, Reel: Paranormal Frequencies in Mark Leckey’s Latest Works

|María Inés Plaza Lazo

Between apparition and archive, ecstasy and extraction, Mark Leckey’s work vibrates at the boundaries of the visible and the invisible, the sacred and the everyday. In “As Above, So Below” (2025), his exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, Leckey conjures a cosmology in which highway lights flicker with spiritual intent and glittery pop music becomes a passageway to the divine.

Mark Leckey, Photo: Alessandro Raimondo

Long before algorithms mapped our dreams, mystics believed that what happened above—the stars, the spirits, the divine—mirrored what happened below. Leckey refracts this maxim through social media samplings and medieval metaphysics, soft toys and surveillance. His works draw on the porousness of video, the ritual of rave, and the instability of memory. María Inés Plaza Lazo spoke to Leckey between his show in Paris and his next, “Enter Thru Medieval Wounds,” at the Julia Stoschek Foundation in Berlin in September, about the practice of glitching, of surrendering to saturation, and of testing the limits of masculinity.

Installation view, Mark Leckey: "As Above So Below," 2025. Images courtesy of the artist and Lafayette Anticipations, Paris.

María Inés Plaza Lazo: The title “As Above, So Below” is ancient and esoteric, yet uncannily contemporary. Helena Blavatsky reintroduced this phrase to 19th-century mysticism; you refract it through club culture and Christian iconography. In your hands, it resonates less as metaphysical truth than as method: flattening hierarchies, collapsing the sacred and mundane, the visible and the invisible, pop music and highway lights. What’s the cosmology at work here?

Mark Leckey: What you’re pointing to is how I’m trying to approach things from two directions: from being completely embedded in pop culture—that's my background—but also from a place of growing interest, maybe even awakening, to spiritualism and medieval metaphysics. That’s really where this show comes from. Like you said, it’s a line between stations of the visible and invisible, and that’s exactly what I’m dwelling in right now.

There’s a contradiction, though—or maybe a dialectic—that I can’t resolve. A kind of spiritual or metaphysical pull, grounded in a historical materialist base: where I come from, how I grew up, the conditions and influences that shaped me politically and otherwise. I’m trying to work through that contradiction. The visible and the invisible. I really like that formulation.And the body—the human body—is the connective tissue between those two realms.

As for “As Above, So Below,” it’s not just about theosophy. That phrase is everywhere now; it's basically a pop-cultural term. But my interest in it goes back further—to the alchemists, to Hermes Trismegistus. There’s a whole cosmology there, a belief in the interconnectedness of everything in the universe. I suppose what I’m trying to do is to resolve spiritual and material concerns that exist simultaneously in me.

MIPL: If the body is the connective tissue between the visible and the invisible, how do you shape the spaces where memory, affect, and magic can actually take hold?

ML: I think it really started to come together at Haus der Kunst, though I wasn’t fully aware of it at the time. When you’re using so much moving image and sound, you can’t just drop it into a black box—it never felt alive in that context. I realized I had to transform the space itself, make it part of the work, so that what you’re seeing and hearing could really land, really hold your attention. That’s when I started thinking more environmentally—not to seduce the viewer exactly, but to pull them into something more like a dream. I hesitate to say “immersive” because it’s become a buzzword, but I wanted to create something closer to a psychedelic experience.

Affect, memory, magic—they’re not content, they’re modes of perception. You’re taken out of yourself. In a successful psychedelic experience, you’re lifted out of reason, out of rational circumstances, and placed into something more like a dream. And a dream carries the potential for magic. Once you leave the bounds of the known, you're already in the realm of the magical. I’m trying to create something closer to the condition of music than to cinema or traditional art exhibitions. Music makes space for the supernatural—for the paranormal. Whereas art often prescribes those things, or is suspicious of them.

I came across something after making the show that really stuck with me. I can’t remember where I read it, but it said, “all pop culture is paranormal.” That struck a chord.

MIPL: In your video work Carry Me into the Wilderness (2022), we hear your voice collapse under the weight of sensation—sunlight, sound, space. But you’re not on a pilgrimage. You’re in Alexandra Park, in a northern suburb of London. Yet the experience was not only paranormal, it became sacramental. Were you documenting the sublime, or did this just happen to you?

ML: I had a sublime experience—and in the moment of that experience, I tried to record it. I thought I was capturing it as an artist: “This thing is happening to me; I need to document it so I can make use of it.” But when I actually started working with the material, I realized I wasn’t acting as an artist so much as being contemporary. Just responding in the way we all do now: transforming every experience into information.

So yes, even in this very profound moment, I was still trying to extract value from it. There’s a suspicion baked into that. Even suspicion about whether I actually had a spiritual experience.I come from a grounded, materialist background—and yet here I am, having these unexpected sacramental or sacred moments. I don’t really know how to reconcile those two realities.So I tried to make the work feel both: exalted and skeptical.

MIPL: Was that feeling of being absolutely contemporary—almost as ecstasy—a refusal of productivity?

ML: I think I confused the artistic impulse with contemporary production. I had my phone in my pocket, thinking of it as an artistic tool—but really, it's an extraction device. The best example of this is how people behave at concerts. Holding up their phones constantly, recording. It’s not really about the experience itself, but about the information the experience can generate. We’re always translating or producing things for circulation and distribution. And artists aren’t exempt from that. We’re not standing above it.

But ecstasy itself—well, a lot of these realizations come after the work is made. I usually follow a hunch or impulse, and then reflect or read afterwards. I read about the etymology of “ecstasy”: it means to be taken outside of the place where you stand. It’s about being pulled out of what you know—your surroundings, even yourself. It’s both an exalted moment and a moment of horror, of fear. The world we live in now—yes, there’s doomscrolling and all of that—but it’s also a kind of ecstasy. A constant state of being pulled out of where you are. It’s thrilling and exciting, but also terrifying and alienating.

Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999. Video. Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London.

MIPL: Doomscrolling can be both: Absolute saturation—your brain literally overwhelmed. People talk about brain rot as a side effect. You also seem to reach for a kind of temporal intensity—the moment where the world arrives all at once. Could we call this a politics of the moment? A refusal of progress in favor of the saturated now?

ML: I’m saturated. I can’t deal with it.

MIPL: All of us are.

ML: I just look at the difference in how I worked in 1999, when I made Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. I was dealing with a limited archive, with limited access. Now—only 25 years later—what’s available is oceanic. It’s transformed everything. We literally can’t work without the internet anymore. I probably would have kept making archival collage work, but that method was voided by the sheer availability of imagery and sound we have now.

MIPL: Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore now feels like a secular icon—an object of reverence, even grief. You once called it a ghost. Has nostalgia become one of your materials?

ML: I mean, that’s part of why I turned to medieval metaphysics—because it becomes so unknowable. I needed to find some kind of analogy between the understanding of God and the understanding of life under capitalism. I don’t mean that in a spiritual sense necessarily, but in terms of trying to fathom the unfathomable. The tools I’d been given just didn’t seem to work anymore. Something shifted so suddenly. The conditions changed in a way that felt abrupt. To go from Fiorucci at the turn of the century to where we are now—it just feels completely disorienting. I became interested in the idea of negative theology—the notion that God is fundamentally unknowable, un-circumscribable. You can’t picture him, can’t really know him in any definitive way. He exists beyond all human knowledge and sense. So, the only way to approach God is obliquely, through a kind of negative path.

Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999. Video. Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London.

MIPL: You’ve said before how images now function less as documents, more as performances or hallucinations. Is video the ideal form because it embraces that instability?

ML: Video is not a true medium in any traditional sense. It lends itself to circulation and transformation. It’s very mutable. It’s kind of the opposite of something like painting or sculpture. I change it constantly. Every time I do a show, the video changes—I adapt the work. But I do worry: is this still the right kind of medium? There’s so much video now. And if all you consume is video, can you even see it anymore?

One of the most upsetting things I heard recently was an interview with a 16-year-old who said, “I don’t listen to music anymore. I’m just bored of it.” I thought, “yeah, of course.” It’s just there, all the time. Like water. But I don’t think that means we should retreat to older forms like painting and sculpture—that feels reactionary. I’m not interested in that. And that’s the point where I sometimes think: maybe I shouldn’t make art at all. That’s where that line of thinking goes.

MIPL: I’d like to ask about the masculine lineage in the figures you invoke: the hermit in the cave, the raver in the dark, the father with a phone during lockdown. But there’s also instability, surrender, even genderlessness in these states of ecstasy. Is your work a way of making masculinity porous, mystical, overwhelmed?

ML: I sometimes look at the work and think: there’s a lot of masculine energy there. There’s a kind of violence that creeps in. But also… it might entirely be the wrong thing to say, but I think that art is queer. It queers you. And the more I make art, the queerer I get in how I understand the world. It changes the way I approach things. And I’ve allowed that to happen. The artists I admired were all gay. They influenced me. I never resisted it. That’s what I’d hope the work does. I think my work is about being a man. A lot of it is about trying to understand what it means to be a man now. But I hope that men are changing. That they’re transmuting. I want to be transmuted.

MIPL: That is a wonderful, utopian thought.

ML: I think it ties into what you said earlier about mysticism and transcendentalism. The promise of the digital is fluidity—it dissolves boundaries. That’s its nature.

MIPL: But what’s interesting is that you create glitches while embracing that fluidity. You constantly interrupt it.

ML: I’m trying to glitch myself. I do have a strong streak of romanticism, and I think I try to put obstacles in the way of that. I’m not repelled by my romanticism, but I see its dangers. Its ineffectiveness, maybe. So, if there are glitches, it’s to get in the way of that. Because if I didn’t, I’d just succumb.

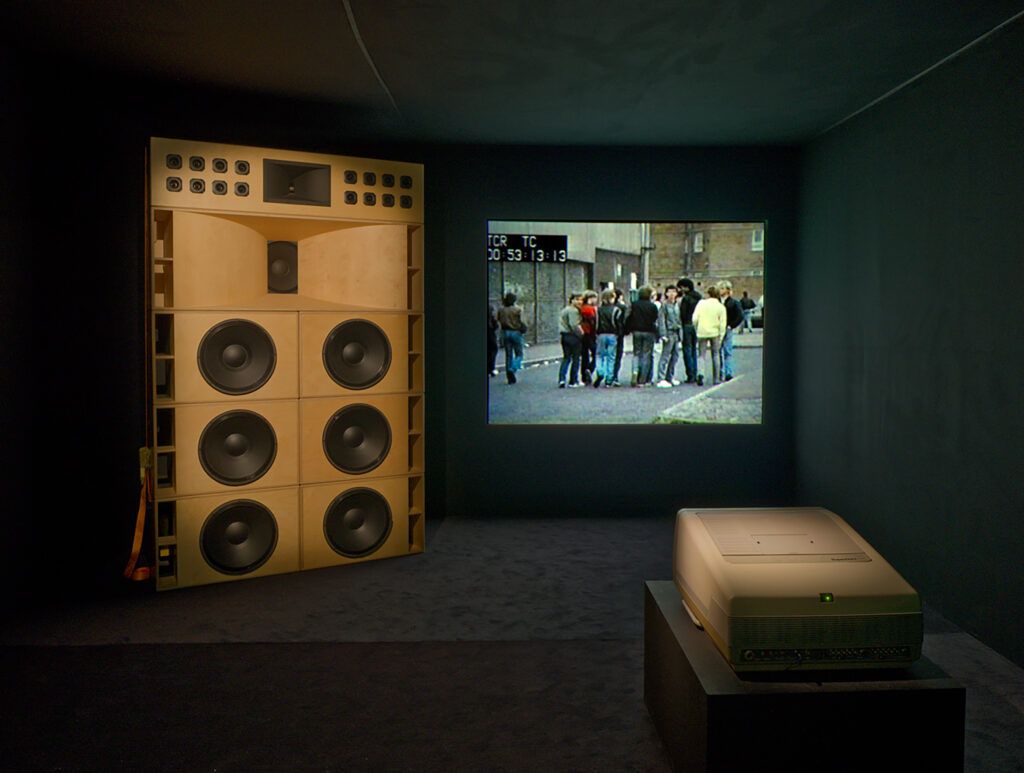

Installation view of Mark Leckey Nobodaddy, 2018, Tramway, Glasgow International, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London. Photo: Keith Hunter.

MIPL: You seem to share this drive to glitch with other artists who metabolize the world in hybrid, polyphonic ways—such as, Christelle Oyiri or Arthur Jafa. Could you speak to the conversations or resonances you’ve had with them?

ML: The main resonance is music. I want art to expand toward music, or the space of music, because that’s where I feel more at home. That’s what I grew up with. To come into the art world—if you’re from a background like mine—is to find yourself in a completely different world. You have to acclimatize, adjust, change yourself. But now it feels like art is more porous. It’s more fluid. Its boundaries are less secure.

Music allows for that. It’s not just democratic—it’s graspable. Anyone can engage with it. I reached out to Christelle because I like what she does musically. I want to be in the same space she’s in. I want more people like her around. My interest in art and music—this might be a very 20th-century idea—but I believe in form. I believe in formal experimentation.

MIPL: Like in Nobodaddy (2018), where you literally give voice to absence through technology. A bronze figure with holes in the entire body is inhabited by sound; a speaker-body that speaks absence and dematerialization, transcending the physical.

ML: Immanence, I think, is the word. Not transcendence—but immanence. Yes. I want to evoke and amplify being alive. It’s as simple as that. Christelle makes me feel more alive. AJ makes me feel more alive. All these things—they amplify that feeling of presence. Of being here. Imminently here.

Installation view, Mark Leckey: "As Above So Below," 2025. Images courtesy of the artist and Lafayette Anticipations, Paris.

MIPL: What does “authenticity” mean to you today—especially when your own biography becomes raw material?

ML: I think I’m still drawn to authenticity—but I’m not quite sure how to put that into words. There’s always a danger in trying to be “authentically working class,” and maybe even more so in trying to make “authentically working-class art.” I don’t think either of those things necessarily serve the working class in any real or meaningful way. So, I’m very suspicious of authenticity when it comes to class. At the same time, someone’s background does matter to me. I still feel a bit disappointed when I find out that someone I admired went to public school and had all the privileges that come with that.

I suppose I do still have a nose for some kind of authenticity—or maybe for a kind of groundedness, or reality. But I also know it’s a trap. I think authenticity is something of a dance. You have to move in and out of it.

Mark Leckey’s exhibition “Enter Thru Medieval Wounds" will be on view from 11 September 2025 to 03 May 2026 at the Julia Stoschek Foundation in Berlin. Saturday & Sunday, 12PM to 6PM.

Credits

- Text: María Inés Plaza Lazo