Resurrecting an Airline: Air Afrique

|Claire Koron Elat

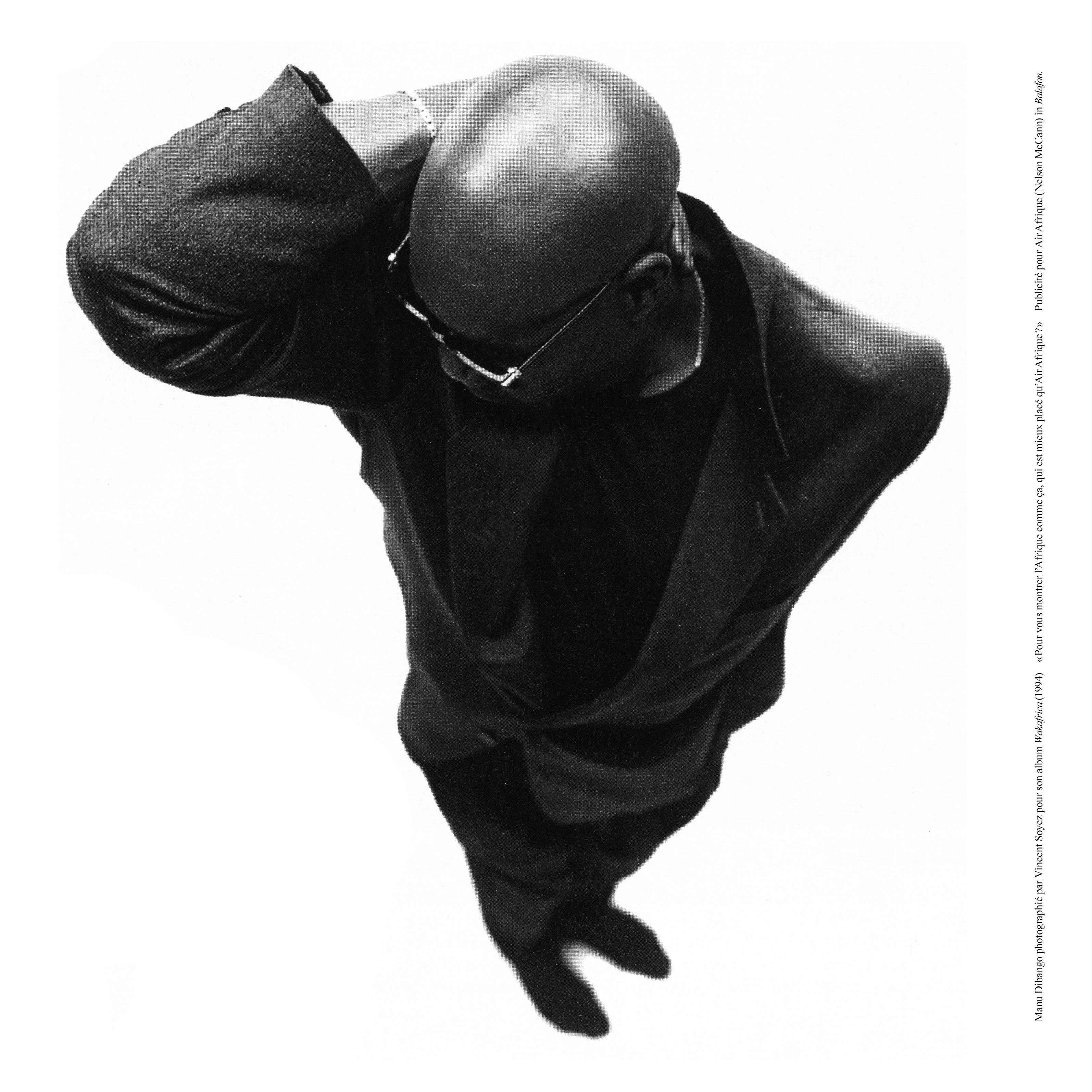

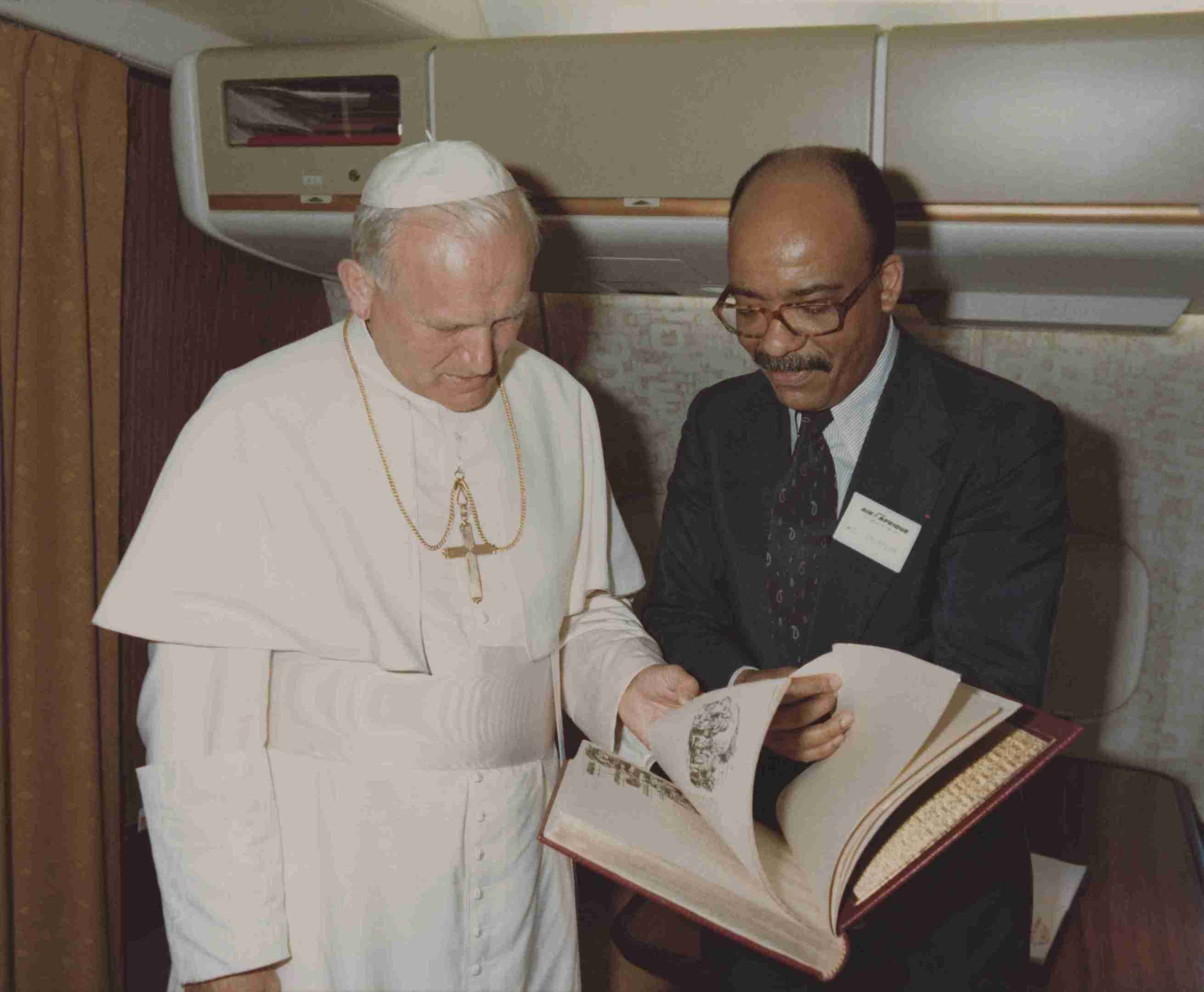

Before its downfall in 2002 from mismanagement, corruption, and 9/11, Air Afrique was the most reputable airline in West Africa. In 1961, an alliance of 11 countries including Burkina Faso, Benin, Congo, and Niger set up the carrier as a medium to collectively evolve their national economies and build relations to the rest of the world. Operating under the maxim of unifying the pan-African identity and decolonizing the continent, the company endorsed cultural discourses in Africa, going beyond a sheer monetary interest. Through endeavors such as the FESPACO film festival, the Dakar Biennale, and the in-flight magazine Balafon, Air Afrique helped evolve artistic dialogues.

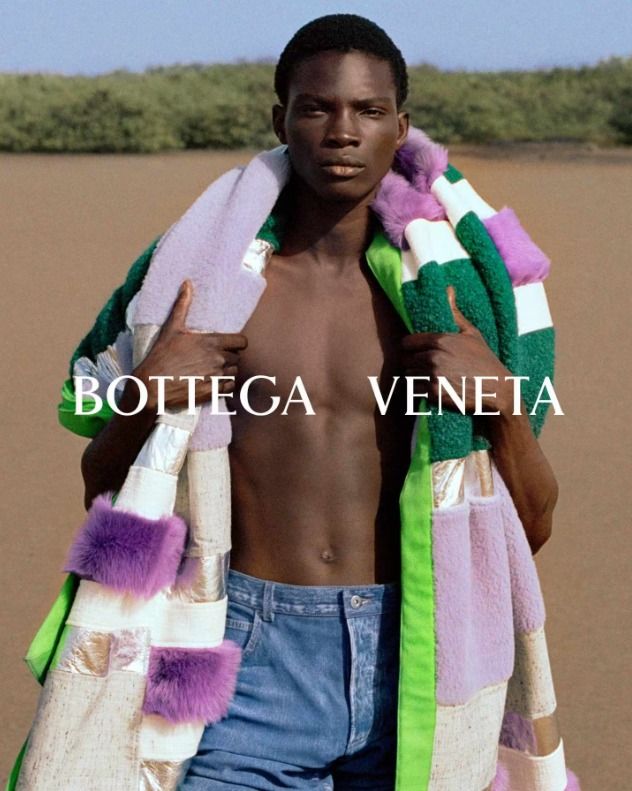

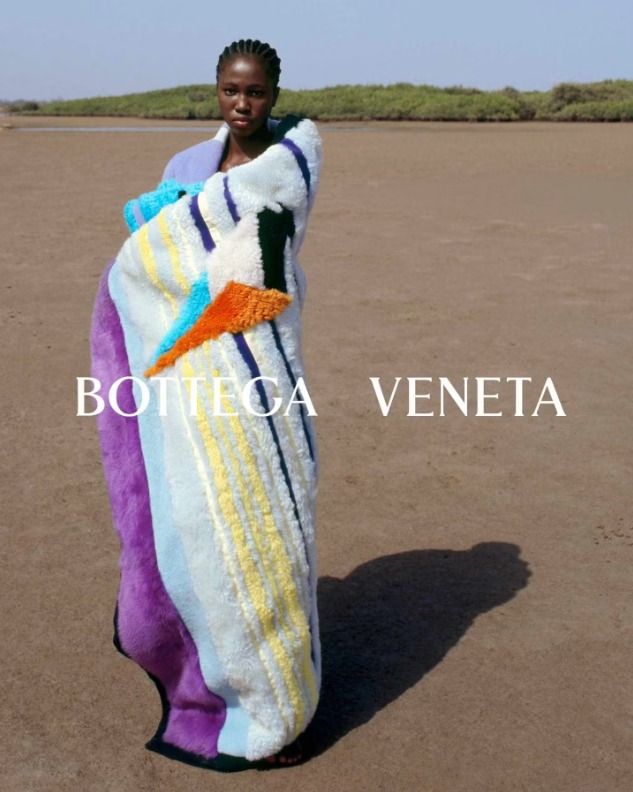

This summer, Balafon was resurrected by the Paris-based collective Air Afrique. Supported by Bottega Veneta, they launched the first edition of their annual magazine, which has the intent to conform with the former airline’s aspirations. On Friday, they will host the first edition of the Air Afrique Stopovers at Reference Point in London, where they will discuss how a historical magazine that is seemingly marginal from a Eurocentric perspective can assist with bringing forward conversations around contemporary African diasporic art and knowledge. Claire Koron Elat talked to the co-founders Amandine Nana and Djiby Kebe about using its archive to create the future.

CLAIRE KORON ELAT: You describe your magazine as combining an airline’s archive with contemporary conversations. What role did the notion of the archive play when you conceived of the magazine?

AMANDINE NANA: The idea was to build something new from the archives of an airline’s in-flight magazine, which was called Balafon. We see archives as an imaginative space, where we can think about rebuilding contemporary imagination and storytelling. Thus, it’s not just about reproducing a certain archive, but about how we can activate these old archives and take inspiration from this space. It’s about recognizing the past, especially as people of African descent coming from a history of neglect.

DJIBY KEBE: Balafon was the magazine that Air Afrique used to publish. They made between 100 and 150 issues between 1964 and 2002 and we collected all of them.

AN: Air Afrique has been a platform for families since the beginning and they used to share personal archives. We have a paper on the oral history of Air Afrique that included memories from all the people who used to work for the airline. It’s not the official archive of Air Afrique, but is rather about how this family was involved in their history.

The way we envision archives is not only in a historical sense. It’s about stating that archives do not only have a documentary function. They also go beyond this and they need to be activated. Post-structuralism is quite important for us. I come from a French interdisciplinary and historical background, and I’ve engaged with thinkers such as Derrida and Foucault.

CKE: So, even though the magazine is in collaboration with a brand, you’re thinking of it as an artistic project, right?

AN: I would say it’s artistic but also rooted in scholarship. The magazine is also a way for us to challenge brands and inspire them to be more rigorous in their way of using their own archives. They could give more context to them and use them with more care rather than just as visually and aesthetically pleasing content.

When we use pan-African archives, for example, we have to be very critical because we are talking about representation of black bodies.

CKE: Hal Foster has suggested that archives don’t only draw on information but also produce it. They use constructive and factual materials but also fictive ones. Since you’re reviving a narrative around an airline that no longer exists, is your magazine also fictional in some way?

AN: You have Paul Kodjo, an Ivorian photographer, for example. In the 1970s and 1980s, Kodjo used to do the commutation for Abidjan, where he used a photo-roman approach. It was a series of photos that were telling a story, almost like a photographic comic. Then we asked a writer to think about creating the dialogue and the storytelling behind the images.

DK: We’ve been working on these themes for three years now. The magazine is an artistic project to talk about archiving but we also did a film club at the Christine Cinéma Club in the sixth arrondissement, where we showed African movies from the 70s and 80s. In fact, Air Afrique used to be really involved in the cinema industry. They used to pay for a lot of movies to be produced and they helped organize film festivals. For us, it’s important to show this side of the airline and to translate it into today’s language. We also did an exhibition two years ago and want to do the same thing in the upcoming months or years. The project should live outside the magazine.

CKE: You take a slow approach to producing a magazine, which goes against the grain of the print economy today, where a lot of newspapers and magazines are under pressure to react to the most current news. This is also driven by the question of how to stay relevant in a market that is so saturated.

DK: We felt that creating an object was relevant because we were magazine readers first.

AN: We are not very driven to produce content. The idea is to print a magazine every year, but to also do exclusive content during the year to keep us connected to what is happening and to what we want to review at that moment. The question is how we can also use the digital sphere to keep this up—but not every day. This is not a daily activity.

CKE: Highly curated print magazines are, as you already suggested, perceived more as objects to collect. It goes beyond simply reading the magazine and throwing it away afterwards.

AN: In the postcolonial era, print magazines were part of the African family’s environment. We want to bring this back and make people interested in buying magazines again. Not just as a commodity, but as something you can cherish. That you can transmit just like an archive.

DK: We didn’t even perceive ourselves as a magazine at first. This wasn’t the main idea when we created Air Afrique. We always knew we were obligated to work on other stuff. But when Bottega came to us and wanted to help us with our project, we felt that it was important to do this magazine.

The question is: How can we make the magazine live outside of itself?

AN: Air Afrique has always been more than just a magazine, so we don’t have this issue.

What we are doing is also very collaborative. We invite artists to do projects in this magazine but that can exist in another way within Air Afrique.

CKE: So, you’re basically imagining the magazine as a form of buying the idea of Air Afrique on a larger scale. Could you also imagine having another physical object that would do the same?

DK: It’s a hard question to answer but we want to do stuff that people can buy. Not physical things necessarily. I want to produce films, for example. And if you produce them, you want them to be shown in movie theaters.

AN: Air Afrique used to be a commercial airline, so having a commercial aspect preserves that heritage. But by being commercial, Air Afrique had the money to support films and to produce goods like magazines, as already mentioned. So, the real story is about Pan-African economic power. We don’t have this power currently, but our venture is about bringing this economic power back to support the Pan-African future right now.

Credits

- Text: Claire Koron Elat

Related Content

BOTTEGA Residency Week Two: TYRONE LEBON

I Saw Mama Africa Collapse: the TABLOIDIZATION of South African Media

What Can Clothing Do: DANIEL LEE at BOTTEGA VENETA

Viscose: The World’s First Bagazine of Fashion Criticism

Father of Surf Magazines JOHN SEVERSON Explains How Surf Mania Was Invented

Brenda’s Business with Rimowa’s EMELIE DE VITIS

Chaos and Creation: Inside the Mind of Vogue Italia Editor FRANCA SOZZANI

Editorial Roundtable: KAZEEM KUTEYI of New Currency