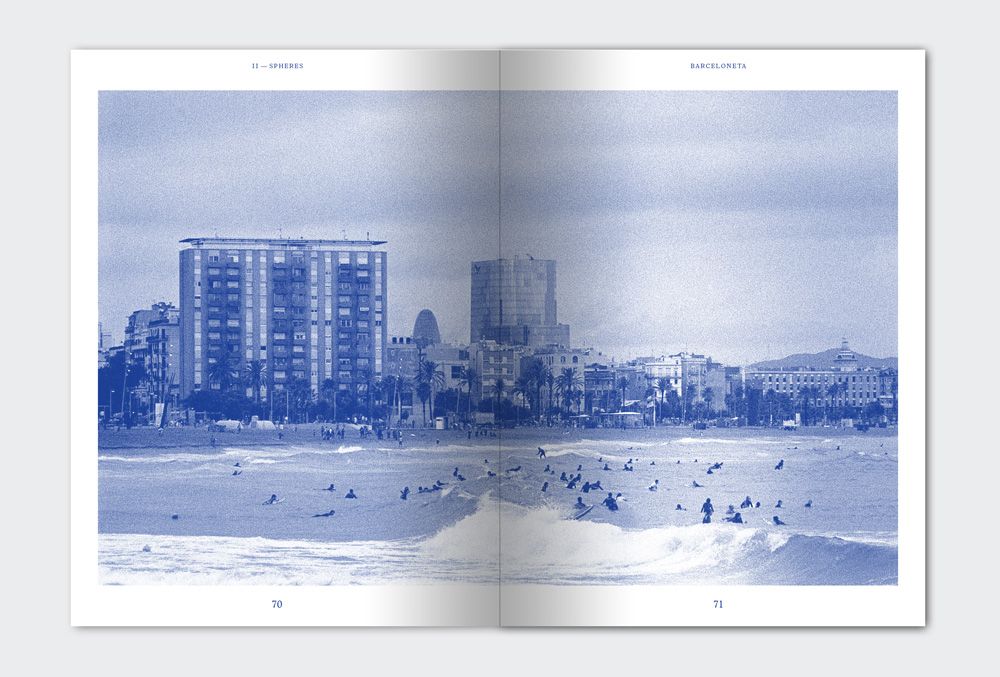

Father of Surf Magazines JOHN SEVERSON Explains How Surf Mania Was Invented

JOHN SEVERSON’s path towards becoming surfing’s first editor-in-chief began with a stroke of good fortune. Upon being drafted to the US Army in 1956, Severson was told that he would be serving out his active duty in Germany. However, after another draftee failed his Morse code exam, Severson’s presence was required elsewhere and he received new orders: “You’re going to Hawaii.”

To his surprise, Severson’s fellow troops were not charmed by the thought of spending two years in the middle of the Pacific. Almost fifty years later, he still recalls their complaints, “We’re going to Hawaii? There’s nothing to do there.” But, for Severson, things could not have been farther from the case. Like every other California surfer from the 50s, he had grown up riding a redwood board and dreaming of Hawaii’s gargantuan waves.

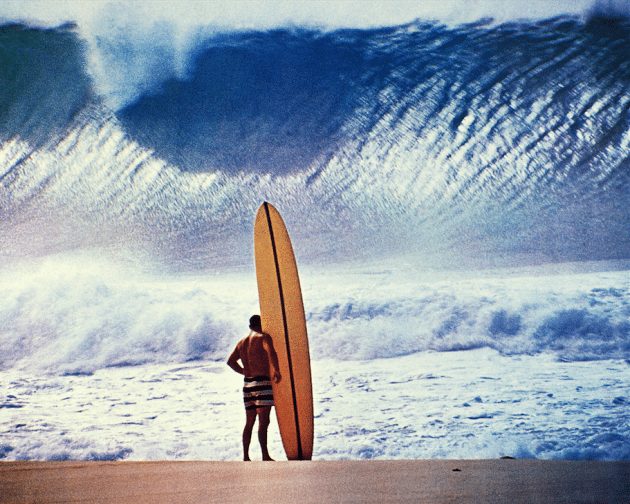

While working for the Army as an illustrator, Severson was encouraged to surf daily as a member of the US Army Surf Team and fell in with a generation of surfers who pioneered new techniques in big wave riding. After choosing to stay in Hawaii, he began selling his drawings and paintings on the beach, eventually being able to acquire the 16mm camera he used to make his notorious surf films.

Filled with DIY exuberance, Severson’s films of the early 60s were created as a way of celebrating the energy of surfing. Citing Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia as an influence, Severson oriented his surf footage around the formal splendor of the body in motion. Captured in high contrast black-and-white, the remaining stills of these films depict bodies contorted and flexed against the enormous force of an ink-black ocean. Composed like scenes from another dimension, Severson’s films communicated the ineluctable verve of what was then a niche pastime, sending an invitation to those who had never surfed.

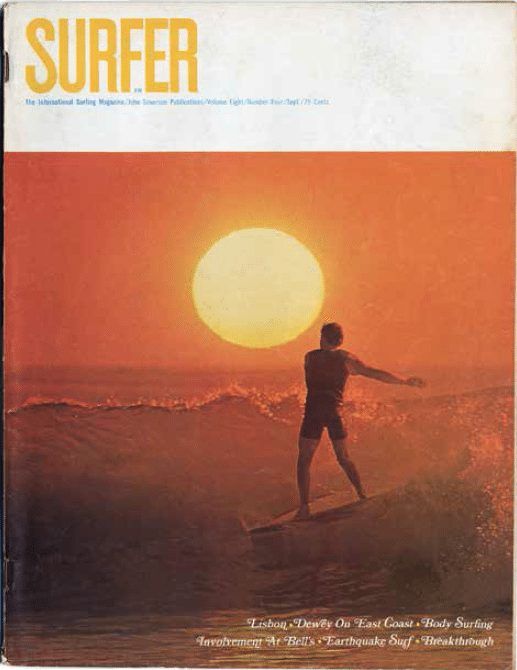

After witnessing the riot-like environment of excitement at his screenings, Severson decided to produce a booklet called The Surfer that he sold during the premieres of his 1960 film Surf Fever. It featured black-and-white photos, writing, and cartoons, as well as surf maps and instructional articles for new surfers. After the booklet sold out five thousand copies, Severson decided to dedicate his attention to creating the magazine now known as SURFER.

As its title suggested, SURFER was a publication that aimed towards expressing the culture of the person who surfed, rather than the sport itself. With hoards of newcomers being brought to surfing by the Beach Boys and Hollywood films such as Gidget, SURFER had a mission to set the record strait. Its editorial program defined surfing as a way of looking out onto the world, an all-encompassing lifestyle that had its own social responsibilities.

Since it was the first magazine of its kind, SURFER gave Severson the freedom to fully craft what has became a massive genre. As surf writer Sam George would later say, “Before John Severson, there was no ‘surf media,’ no ‘surf industry,’ no ‘surf culture’ – not at least in the way we understand it today.’”

In anticipation of his upcoming book SURFER, which features Severson’s paintings and images from his personal archives, John Severson gave 032c a call from his home in Hawaii.

Being a surfer your whole life, how would you describe the experience of being stoked on a wave?

It’s like a beautiful sensation of dance with the added dimension of being in nature. There’s this whole force of moving water, and as you ride, you harness this water. Then, as your abilities increase, you can go farther and deeper into the wave, and into more radical positions – like off the top, off the bottom – and there are these weightless sensations. It’s another dimension.

You’ve often been credited as the inventor of surf media, with your films in the 60s and with SURFER magazine. What was it that made you want to create media around surfing? Was it this experience of seeing the world from this other dimension?

At first, I looked at it as something so beautiful that I wanted to share it. The old-timers had shared it with me, and I looked at surfing as a kind of celebration. I then began to dream of a life in surfing, so that I could surf and I could continue it by making enough money off of whatever else I did. That led me to go into films, and it worked. The kids who saw these films were so stoked that they wanted pictures, so I started selling them black-and-white pictures for a dollar. That made me think that perhaps a magazine would work. That was the beginning of SURFER magazine, which was the beginning of sharing what was going on with surf and surf culture.

What was surf culture like in that nascent period?

Well, it was just emerging back in the 50s with these very strait, lifeguard-type surfers. Back then, the main developments that were going on were happening with the surfboard itself – going from big redwood boards, to redwood and bolsa combinations, to all bolsa wood boards and what they call the “Malibu Chip.” The other development was the surf trunks, which at first were these tight lifeguard trunks. We began to realize that it was hard to sit on the board with these tight trunks, so we loosened the trunks up and strengthened certain parts and put on a pocket for the wax. But then, when all the Hollywood surf films came out, there was a misconception of what surfing was, because the people who wrote these films were old people who had never surfed. They made these stereotypes, and so when new surfers came into surfing, they thought that attracting attention and vandalizing areas was what surfing was all about. It could have gone on that way, but I was holding the reigns of surfing right at the beginning.

Why do you think these Hollywood depictions of surfing were so off-base? What were they missing?

Their motivation was really money in the end. Money and power. It’s just a different motivation than when two or three guys make a film about surfing and they’re putting all of their stoke and love into it. That’s going to be a better surf film than what Hollywood puts money into.

So during the beginnings of SURFER, you dedicated the message towards dispelling this rebel image that had come to surround surfing through Hollywood films. But then, towards the end of the 60s, the magazine went into some radical terrain – you had stories about Vietnam, you had images addressing Apartheid and segregated beaches, you had stories on environmentalism. When and how did the magazine become more political?

You can imagine that in 1960-61, we had no financial clout. There were no businesses organized to support us. Even the businesses that sold trunks and boards were basically run out of garages. We weren’t of interest to the general public, and that’s why they started outlawing us at surf spots up and down the California coast. I realized that we had to improve this image or we don’t have a chance. I know that sounds like a bit of a sell-out, but that was the only way to make it in those days. So we asked the readers to straiten up, because it would be a matter of losing their surf spots, and they really did. But we were still surf rebels and later on we became a force. We became a financial force and we became a political force. We could move a lot of people to meetings and change opinions of the public. So we weren’t afraid to tackle political issues in the late 60s.

Your influential surf films from the early 60s – such as Surf Safari and Big Wednesday – were never reproduced or archived. Although they were your entrée into starting SURFER,they exist now only in myth and legend. You said in an interview that you were never really keen on preserving these films, saying that it was impossible to “can the relationship between stoke and time.” What did you mean by that?

Well, everything was happening so fast year to year. Now, you look at surfing, and it’s hard to say we’ve come so far from 2013 to 2014. But back then, from 1959 to 1960, there were huge developments in surfing. You know, for surfers in 1960, the 1959 surfers looked like kooks. At best, you could save half a dozen shots that were timeless. Every year things were just jumping, and the development was really fast, and I couldn’t see how those movies would be interesting anymore as they were. The music was also lifted off of records and played live at the showings along with the narration, so I was a little fearful of putting those down on a soundtrack, because I’d have to buy and clear music. So it got to a point where I had to make a decision, “Would I pay all that money to can the film and buy the music rights?” I decided no, just full speed ahead.

You decided to just go with the momentum.

There was so much stoke. The audiences would just cheer and clap, and they were so stoked on what they were seeing. But when I went back to show the new film the following year, there were a couple of instances when they wanted to see the old film again, and it would look flat compared to the original release. That’s the stoke you couldn’t can.

Do you see anything today that you are really attracted to in surfing media?

I’m a big wave rider and I’ve always been a big wave rider. I relate to that and I feel it. That’s the thing about surfers, is that you can feel the pressures, and you know how light you have to be, and you know where you have to apply pressure to make the turn on a big wave. All of those things are captivating for me. I rode a very big wave once and that was still on the smaller side of what they’re riding now.

How big are we talking?

We’re talking so big that it just looked like a skyscraper. I thought, “This can’t be real!” I tried to go into the wave, and when it broke on me, I dove underneath. I got pitched over the falls and slammed on the bottom for two waves, saw the stars, said goodbye to my parents and my family, and blacked out. The next thing I know, I’m taking a big gasp of air up at the surface. The guy I was with was like, “What are you doing here? I thought you were on the shore.”

At the beginning of big wave surfing, a lot of you guys were discovering new waves and new places to surf. What was that sense of adventure like?

The adventure and danger wasn’t only about discovering new places. We didn’t have any weather reports. We didn’t know what was going to happen. We’d paddle out and be like, “Wow, the surf is coming up.” You could just keep paddling, and it’d keep getting bigger and bigger. That’s what happened with Woody Brown and Dickie Cross. They started paddling out at sunset, and it was already big, but there was a long lull, so they didn’t realize that it’d keep getting bigger and bigger. They ended up so far outside that they decided to paddle out to Waimea, and somewhere along the line, Dickie Cross got picked off and was never seen again. Woodie Brown eventually caught a wave and he arrived on shore naked and battling, so he lived through the experience. But that was something that could happen to us any time we paddled out, and we all knew it.

After running SURFER for almost a decade and growing it into this unprecedented forum for surf culture and surf journalism, you sold the magazine at the beginning of the 70s and moved to Hawaii. How did that decision come about for you?

Before I married my wife Louise, she asked me if I had a ten year plan, and I told her that I did. I was going to work for ten years making surf media, save something, and then leave so we could spend the rest of our lives adventuring, travelling, and painting. I wanted to live an easier life – not as a starving artist, but as a semi-starving artist. Sometimes plans like that don’t work out, but this one did. It worked!

Credits

- All images copyright: John Severson, courtesy of Puka Puka