Editorial Roundtable: KAZEEM KUTEYI of New Currency

|Octavia Bürgel

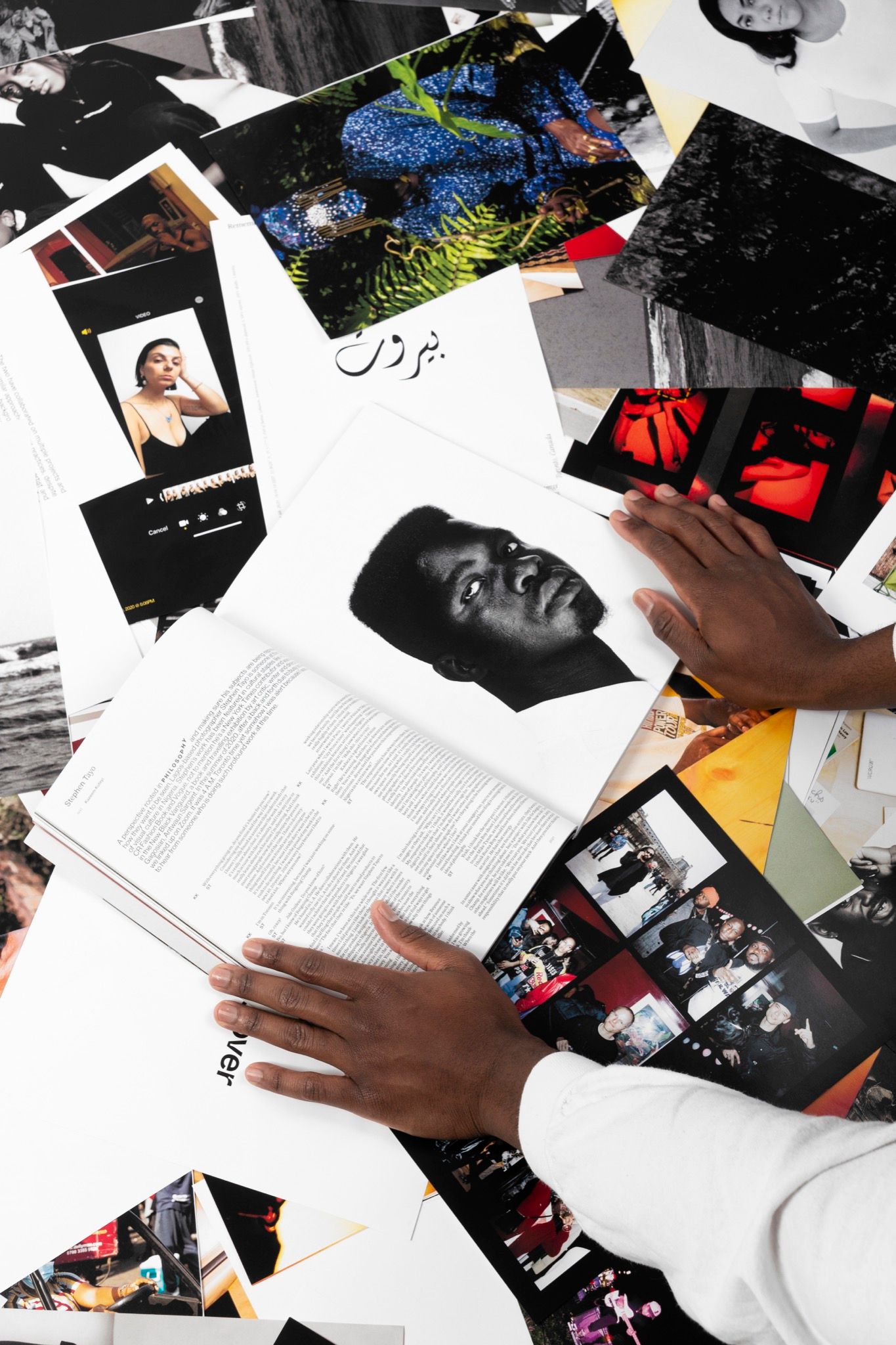

Toronto magazine-slash-incubator New Currency celebrated its official launch last week. But the publication’s digital presence goes back to 2015, when two young people raised on Tumblr but fascinated with print ephemera booked a trip to Paris with the goal to interview anyone who would give them the time. The platform has since evolved away from the digital sphere and into material form, which co-founder Kazeem Kuteyi says was always the intention: “New Currency was supposed to be in print originally,” he says. “We thought, ‘let’s travel and meet people and put it into a magazine’ – but then we realized that we actually didn’t know how to put a magazine together.”

Making the internet New Currency’s original home allowed Kuteyi and collaborator Kahlil Hernandez to build a brand by hosting events and a podcast series – generating curiosity and a modest base of followers years prior to its print debut. “It became this really interesting community, which was questioning what it means to exchange ideas across a bunch of different mediums,” Kuteyi says.

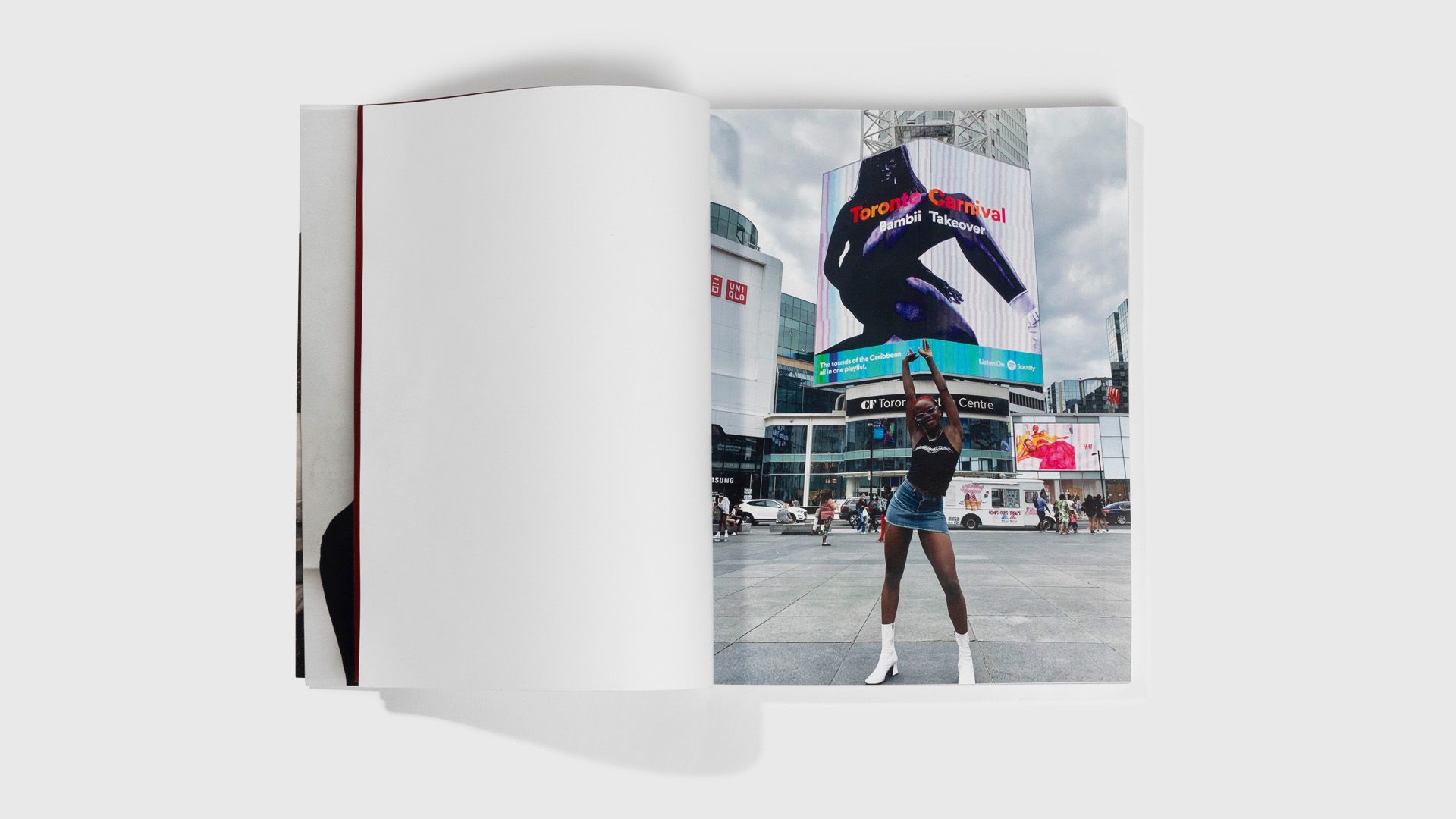

Though the publication has firmly planted its roots in Toronto, Kuteyi is aware that “you can’t really make a city-focused magazine in this hyper-digital world.” That’s why, when he commissioned me this past autumn to interview Bambii – a DJ of proud Jamaican heritage and a Toronto upbringing – I jumped at the opportunity to “travel through Zoom,” as Kuteyi puts the remote conversations that have become the norm. “We’re all so connected, so we asked: how does that global interest live within a print magazine that still tells a cohesive story about Toronto?”

Octavia Bürgel: Would you say you’re crafting that relationship to Toronto through the combinations of individuals you’re putting together? For instance, someone like Bambii, a native Torontonian, being interviewed by me – a New Yorker living in Germany. How do you balance cultivating local community and branching outwards?

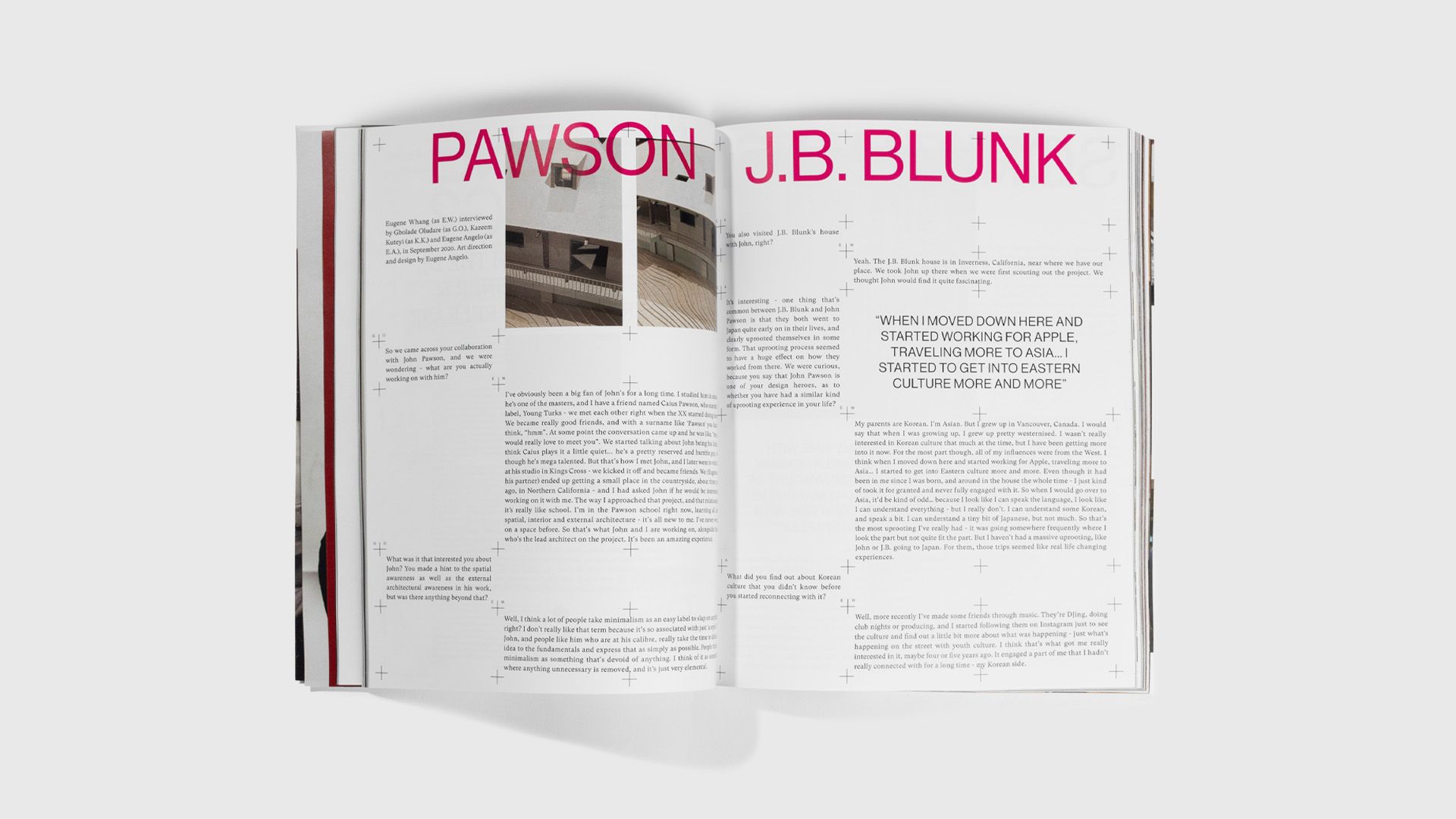

Kazeem Kuteyi: Exactly, it’s very intentional. For instance, we included Eugene Whang, an industrial designer and DJ with a label called Public Release. I thought it would be interesting to bring in these Central Saint Martins kids, friends of mine in London, for that piece. We had a whole research process of putting together the questions to interview him. That was interesting, but these combinations also come through the curation of the pages. Beside that interview with Eugene Whang, there’s a piece on an industrial designer from Nigeria, who I asked to render his photos. So in the end, you have this emerging industrial designer from Nigeria, beside this interview with Eugene Whang. Hopefully we’ll get to the 20th issue, and then they’ll be existing in relation to the next person in the magazine.

Speaking to this idea of bringing Toronto the world, I had a writer here in Toronto – her name is Melissa – do an interview with a UK artist named Sandra Poulson. She did this project called the Angolan Archive, where she went to Angola to really tell the story of what’s going on there through artifacts, and collect all of this information. When I read that piece, it was clear they really found an understanding with each other, too. I think that is a very interesting way to create a magazine – not necessarily “let’s record a moment,” but more “let’s create a process” where hopefully, outside of the magazine, something can happen.

The tagline for New Currency reads “A New Institution”. We live in a moment of intense resistance to institutions as we know them. We’re universally fed up. So, where does that leave New Currency? As a generation, we’re abolishing the old way of institutions, but the way you speak about your publication is already striving to reclaim the same language.

When I think about institutions, they’re always archiving. With New Currency, we don’t necessarily have a building, but I think that an institution can also exist across a bunch of people’s homes. Institutions are usually made by a group of people who have money, who came together to build these structures. When these people are in control of institutions, they prioritize the stories that affect them, and when the general public comes to these institutions, they think that what they see is the end-all and be-all of society. Which is completely wrong, right? When New Currency is claiming this sort of language, it’s us acknowledging that there is power in words. It’s a choice about generating that type of reverence. And if we are reclaiming this language, then it needs to exist in a medium—whether it’s this magazine, or whether it’s a pop up space.

So the term “institution” is just a barometer. It’s about setting a standard.

Exactly.

Tell me about the rest of your team. Is the idea behind New Currency that it’s entirely produced by young people of color?

Basically the team is my friend Kahlil Hernandez, who’s Black – and my other teammate, Daoud Tabibzada, is from Afghanistan. In terms of the external team—the group of writers—it’s all very diverse. I don’t necessarily want to box myself in, in terms of who I work with or don’t work with. But at the end of the day, it’s a Black person who’s editing it, so it’s rooted in the Black experience in that way.

I don’t consider New Currency to be a Black magazine. I can only claim: this is what it is, and I happen to be Black. My experience and the content just happen to live within this way of thinking because I’m Black. It would be very easy for me to say, “Yeah, this is the Black magazine,” and take advantage of this whole moment that’s going on around blackness where it’s being commodified and almost talked away. A photographer in New York – a friend – was just like, “I feel like I’m making blood money because of the way everybody is hitting me up for jobs now.”

There was a moment this past summer when I was watching all of these publications roll out their retroactive, “we stand with you” statements and all this bullshit. I remember Ferguson. I was in high school, I haven’t forgotten. And it was the same then—there was a wave of tepid institutional support, and then it dried up, you know? So I was looking at every publication sideways all summer. Like, “I don’t believe you.” I still do not believe any of it.

There are so many publications that suddenly were saying “we’re Black now!” Black this, Black that. And even in the New Currency magazine, there is some of that because we are still recording this moment. Even though it’s not necessarily focused on George Floyd, I knew that people were feeling intensely, and I realized that I needed to be very careful with how I was pursuing people to submit their pieces for the magazine. I was very gentle with the Black creatives who were part of this process. I remember I was in a barbershop and the barber said, “You got to be gentle with people who look like you right now, because people are starting to wake up.” That’s why I told contributors if you can’t meet this deadline, it’s okay.

I think in the magazine, we’re also speaking to the future. For example, there’s this piece on the future of Black music videos, which we did with Sharine Taylor. My friend wrote that piece—she’s interested in film, and she’s always pushing interesting narratives from the Caribbean. We also paired her up with Lauren Kramer, a professor at University of Toronto, who works in the cinema studies department and who is big on music videos. I was curious about that because I was wondering, “what will music videos look like with everything going on?” Lauren Kramer was like, “I don’t think music videos need to respond to what’s going on. They can be bubblegum and they can be fun,” and I feel like that’s what I want to see from music videos in general. Everybody wanted Kendrick Lamar to drop an album this summer, you know? It’s so predictable, and I’m so glad he didn’t.

What was your creative background before New Currency?

I was born in Canada, but I also grew up in Nigeria. My parents took me there to learn the culture, and I think I found myself there. Because I was Canadian, a lot of people in Nigeria were interested in my perspective, and I always had a passion for sharing information with people. I used all my allowance money to buy film, just to take pictures of my friends. Since I grew up in a Nigerian household, pursuing music was off the table—that was a myth. That can’t happen. So I went to school for criminology. It was an interesting thing to study because obviously you learn a lot about psychology, and about people – about why people commit crime, that there are so many factors to why people engage in criminal behavior. I think it helped me develop a different type of empathy.

Then, I enrolled in advertising school. I remember somebody telling me, “the industry is so white.” And I said, “Who cares?” I’m just going to do my thing. So I started a personal blog. Through that blog, I met Kahlil, who’s now the photographer for New Currency. I remember sitting at a café and saying, “Yo, imagine if we went around the world to interview people.” The next day we booked a trip to Paris. I went on Instagram and found a bunch of people just by saying: we want to interview you, I want to interview you. That’s how New Currency started.

Your criminology background must have given you a leg up in asking questions, gauging and interpreting people.

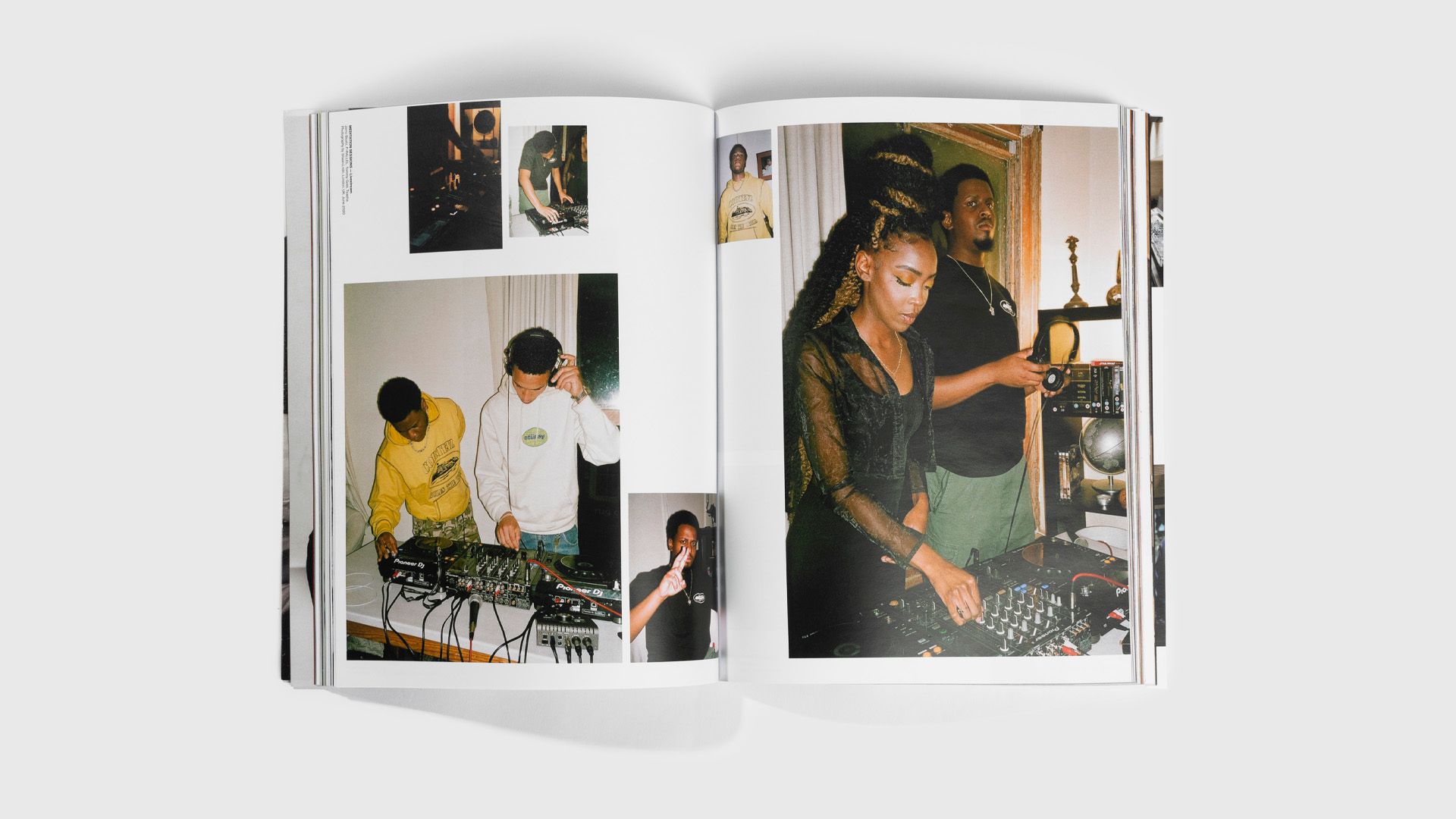

I have a really good read on people. I’m really in the “criminal’s” head, due to all these stories that I’ve had to ingest, and the theories I’ve had to study. The research process that I’ve gained from my criminology studies has bled into the way we do New Currency. For instance, we did these raves this summer, which we framed through the lens of doing research – thinking about the surveillance of Black people in public space, and the role of architecture in community. I was interested in what type of music plays in various spaces. Like, can you play Playboi Carti in an outdoor space? Can you play Playboi Carti in an abandoned building? What does it sound like? Or are you playing techno? You get the idea. We were playing with music in architecture. We’d pull up with a generator, two speakers, CDJs, and before we knew it, the location was packed.

We were asking: what does the city look like for youth culture in the Covid world, if all these music spaces are closing down? I remember, I put out a call on Instagram: “I need to chat to an architect, ASAP,” I got a contact and I reached out saying, “hey, would you want to contribute some initial ideas to imagining what spaces for youth culture can look like in a post-Covid world?” The project that the architect developed in response is in the magazine, and we’re working on making it into an exhibition this summer. We hope, if people come to this exhibition, maybe they will start to rethink real estate in Toronto. If they do that, could they start to rethink who they vote for, or how city planning works? This is the type of thing I mean when I talk about building an institution. It’s creating a platform to really engage.

I get this impression that when we go on social media just to scroll, we’re all universally taking a big step back. Traditionally, you see things in print format first, and then eventually they get a digital presence. Yet it feels like you’re working backwards by founding New Currency as a digital platform first. And outwards, too, with the IRL exhibition you mention.

I think you need to create multiple touch points for people to enter. I think not everybody wants to read. Some people would rather listen to a radio show, and that’s why we do radio shows. Somebody else would rather come to a party, and that’s why we do a club night or a panel talk. There’s something here for everybody.

Credits

- Text: Octavia Bürgel

- Photography: Kahlil Hernandez