Inside Ukraine

|Henry Levinson

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, news coverage has often overlooked the day to day lives of people impacted by fighting. Photographer Joshua Olley met with people living alongside the conflict, and documented the many faces of lives interrupted by war.

Henry Levinson: Getting into Ukraine seems incredibly difficult logistically. How were you able to get access to the country?

Joshua Olley: Getting into Ukraine is a long journey, totaling two days of travel. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion all civilian airports have closed, the only way to get in now is to fly to a bordering country then take the train. For my third trip, I flew to Kraków, then took a train to the border town Przemyśl in southeast Poland. From there, I took another train to Lviv that lasted 5 hours, then an overnight connecting train to Kyiv. Ukraine has one of the most interconnected railway systems in Europe. Overnight trains are a big part of the culture, and the main way people travel, and even during wartime trains leave regularly.

This project stemmed from the relationships I built up over three consecutive trips. Before I felt legitimate taking pictures, I engaged in conversations with the friends I had in Ukraine and took two different trips in. Taking pictures in this sort of situation is difficult because stakes are high. I felt a real need to capture people’s story first and foremost. It was therefore crucial to establish connections before going in to take portraits.

HL: How did you meet your subjects? How did you choose who you worked with, and why? Also, I'd like to know a bit more about the translator(s) you worked with while in Ukraine, as I want to credit them alongside your work.

JO: On my second trip I stayed with a household of academics and artists who fled the east and were living in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv. By my third trip in May, most of them had returned to Kyiv. Most had since become close friends and were incredibly generous with sharing information and knowledge. Through those friends, I was introduced to a network of people in Kyiv and Kharkiv, this allowed me to set foot into intimate groups of people. They introduced me to their friends in Kyiv who then worked as translators / fixers. The main group I worked with were Andres, Denys, Nana and Sveta. It’s hard to meet ‘locals’ without people like them.

Andreas is a tattoo artist who comes from a village in northern Ukraine. Through his connections, I was able to take portraits of young people hanging out in Kyiv. Denys is a civil engineer with an extremely erudite understanding of Ukraine’s history. He brought me to places like the crematorium and generally helped shape my discourse and deepen my understanding of the Ukrainian situation. Nana is a young documentary filmmaker who I joined while she scouted locations in Kharkiv. She introduced me to three soldiers working for the Ministry of Defense. It was during this trip that I came into close contact with people on the front lines and the cities devastated by the Russian attacks. Sveta is a friend of a friend, who had a distinctly nationalist upbringing. Her family is deeply invested in volunteering for the cause, and her brother is currently fighting on the front lines. She translated, put me in contact with locals and brought me to her village Moshchun outside of Kyiv which had been totally devastated by the Russians.

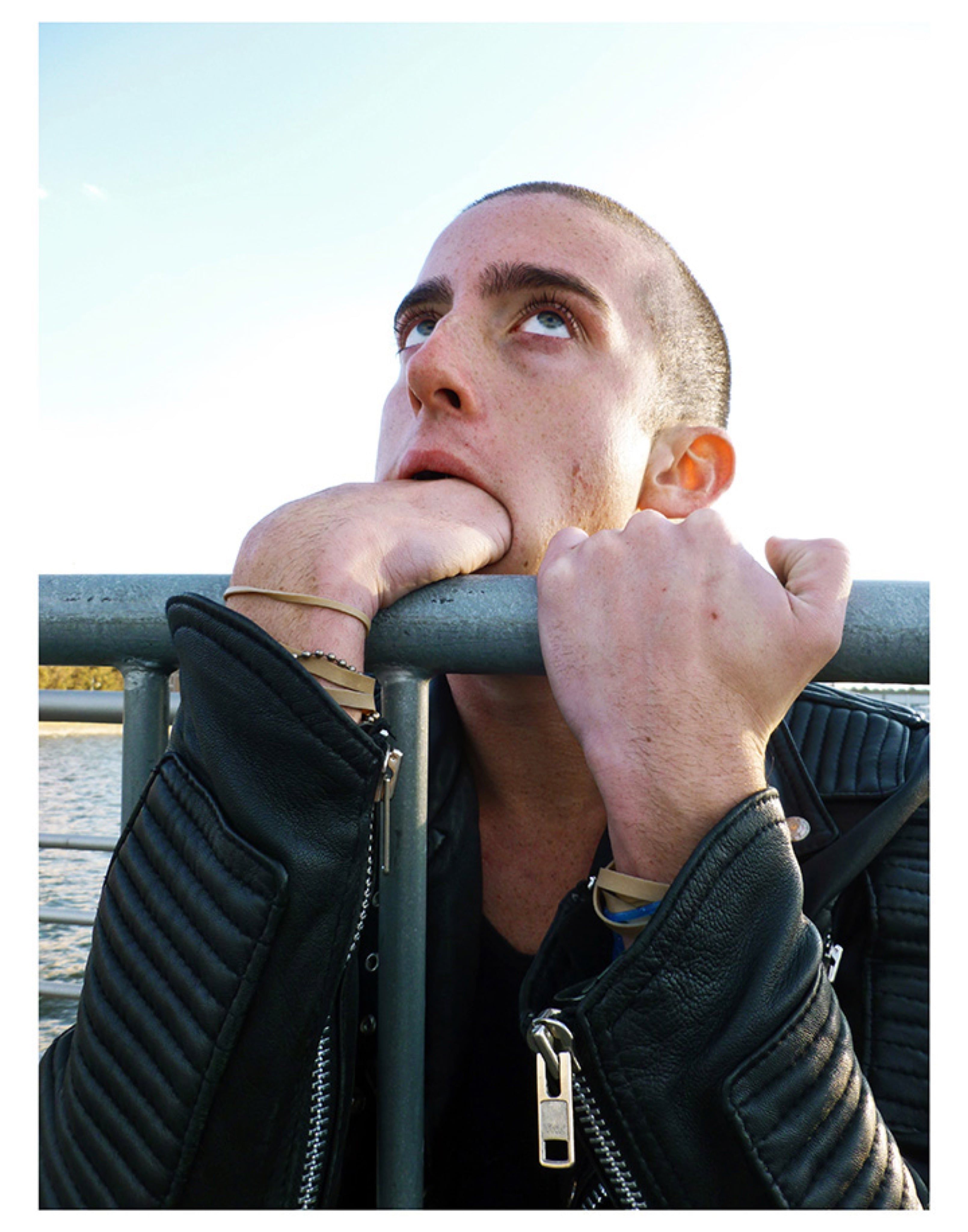

It was important for me to highlight the individual traits of the people I met. Youth culture is largely pro-democratic, anti-corruption and supports the full integration of Ukraine into the EU.

HL: Once you were on the ground in Ukraine, what were your initial thoughts? War is complex and emotions are not always logical. How would you describe the mood in the different cities you were in and of the people you met? What were the differences between Kyiv and Kharkiv, for example?

JO: On my first trip, things were extremely chaotic. Every train and bus station was filled with thousands of people, mostly women and children, coming and going from all over Ukraine. People seemed to be acting on adrenaline and not necessarily on logic. No one knew which direction the war would take. On the second and third trip, things seemed a bit more rational. In Kyiv daily life seemed to be back to somewhat ‘normal’ despite a curfew and air raid sirens. People returned to their routines, hanging out at cafés and parks.

The mentality today for many in Ukraine is one of certainty, everybody I spoke with said they believed they would win the war, without a doubt. That certainty created a communal feeling from which arose a certain optimism. That said, people still voiced their concerns when talking of the war now raging in the east, and they were afraid the world would forget them.

HL: I noticed that many of the young fighters you photographed have specific patches on their military fatigues. Through a bit of research, I found that some of the groups affiliated with these patches, namely the Krakens, have right-wing political affiliations. This is a common phenomenon when reporting on groups fighting in Ukraine, but I wondered if you might be able to expand a bit more on their affiliations, and what you learned speaking with them.

JO: The Kraken unit was formed by Azov Battalion veterans after the Russian invasion, consisting of volunteers steered towards the defense of Ukraine. Krakens, specific to the Kharkiv region, stand to become one of the most famous bands of volunteers in Ukraine. The people who join this group, many of whom are over 35 years old, represent a wide range of political activisms. That said, a minority of them maintain right-wing currents of Ukrainian nationalism.

It is important to underline that Russian propaganda has exacerbated the role and weight of right-wing nationalists in Ukraine. I am hesitant to speak about it because it is a convoluted and manipulated subject. All I can say is that the people I spoke with, who were part of Kraken, where not right wing.

It’s difficult to look at nationalism in Ukraine through the western gaze. Ukraine is in the process of affirming its sovereignty, its borders, and its national identity. Although there have been some members affiliated with a right-wing political ideology, which sometimes harbors anti-Semitic and white supremacist ideas, the majority of its members are moderate Ukrainian youths who volunteer in the Kharkiv region in order to defend their country from the Russian invasion.

In Bucha, where for the first time the international community learned of Russian war crimes, there was a serious weight in the air. The citizens of Bucha were piecing their city back together when I was there. People were gardening, rebuilding homes, and businesses were reopening.

Kharkiv, on the other hand, was completely different. The city was a ghost town. The only people on the streets were military personnel and journalists, and only a few businesses were open. Kharkiv is known as a university town. I visited the old student hub, where before hundreds of youths would hang out in bars and pizza restaurants. It was here that I met Dimitri, who ran a coffee shop. He and his young daughter had decided to stay.

Despite the onslaught, for Dmitri, staying in the besieged city was his only option. In the winter, when war first broke, he had sick relatives who needed his support. Dimitri stood in lines for medicine, sometimes waiting up to 10 hours. Understanding he was needed in Kharkiv, his wife and child did not want to go alone.

I asked Dimitri how he felt about his decision to stay despite the danger, to which he answered, “The main reason was faith in God, that he would save us and our city! It was a difficult but balanced decision for our family.”

Every building in the city had signs of war. Shrapnel holes were everywhere, windows were broken, or completely bombed out. Air raid sirens were frequent, and the distant sound of artillery shelling was constant. The people I spoke to were tired. I felt it in their energy and demeanor. That’s the effect of constant shelling, you lose motivation and vitality. This was in stark contrast to Kyiv.

HL: What were some of the more mundane moments of your trip that stuck with you? Instances of fighting are of course, the dramatic angle many outlets report on, but it's often the day to day lives of those living alongside warfare which can give some of the best insights into the nature of the conflict.

JO: One moment that will always stay with me was during a visit to our friend's village, Moshchun, which had been destroyed. We spoke with an older couple who showed us the damage done to their home. The entire second story had been destroyed and the house was riddled with bullet holes. They showed us pieces of a bomb that landed in the back garden. Even though their home was almost totally destroyed, they had the most beautiful vegetable garden I had ever seen. When we left, I turned around to see the husband weed whacking in front of his and his neighbor’s homes. Their street that was full of bombed out cars and the shells of homes. I will never forget the sheer amount of pride I saw in that moment.

HL: The media has been awash with images of burned-out buildings, and leveled cities in Ukraine. While your work does include images of the destruction wrought by the conflict, there is a particularly warm focus on the people of the country. How do you balance this in your work?

JO: I witnessed the total desolation of a country at war in stark contrast to the unapologetic individuality of ordinary people. In this series I wanted to highlight this contrast. War can quickly become a blurry mass of images where clichés thrive, and individuality is lost. It was important for me to highlight the idiosyncrasies of the people I met. The simplicity I chose in the composition of the portraits is a purposeful choice, as I believe this is the best way to emphasize these traits and make them the focal point of the series.

Credits

- Photographer: Joshua Olley

- Interview: Henry Levinson

Related Content

032c Donations to Ukraine

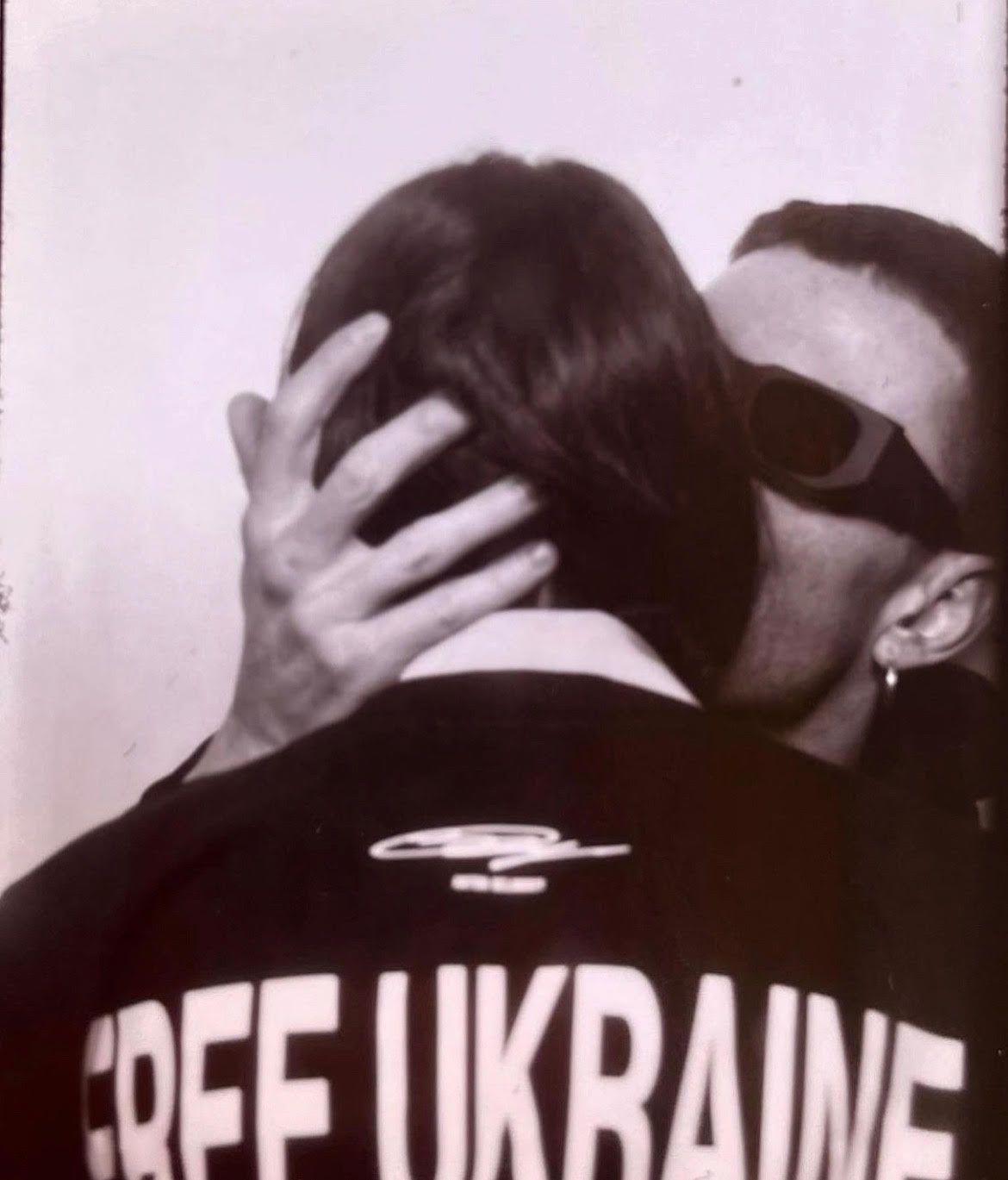

Wear Your Support: ANTON BELINSKIY and 032c's FREE UKRAINE T-Shirt Design is Now OPEN SOURCE

Ukrainian Designer YULIA YEFIMTCHUK’s Extremely Soviet Vision of Post-Soviet Youth

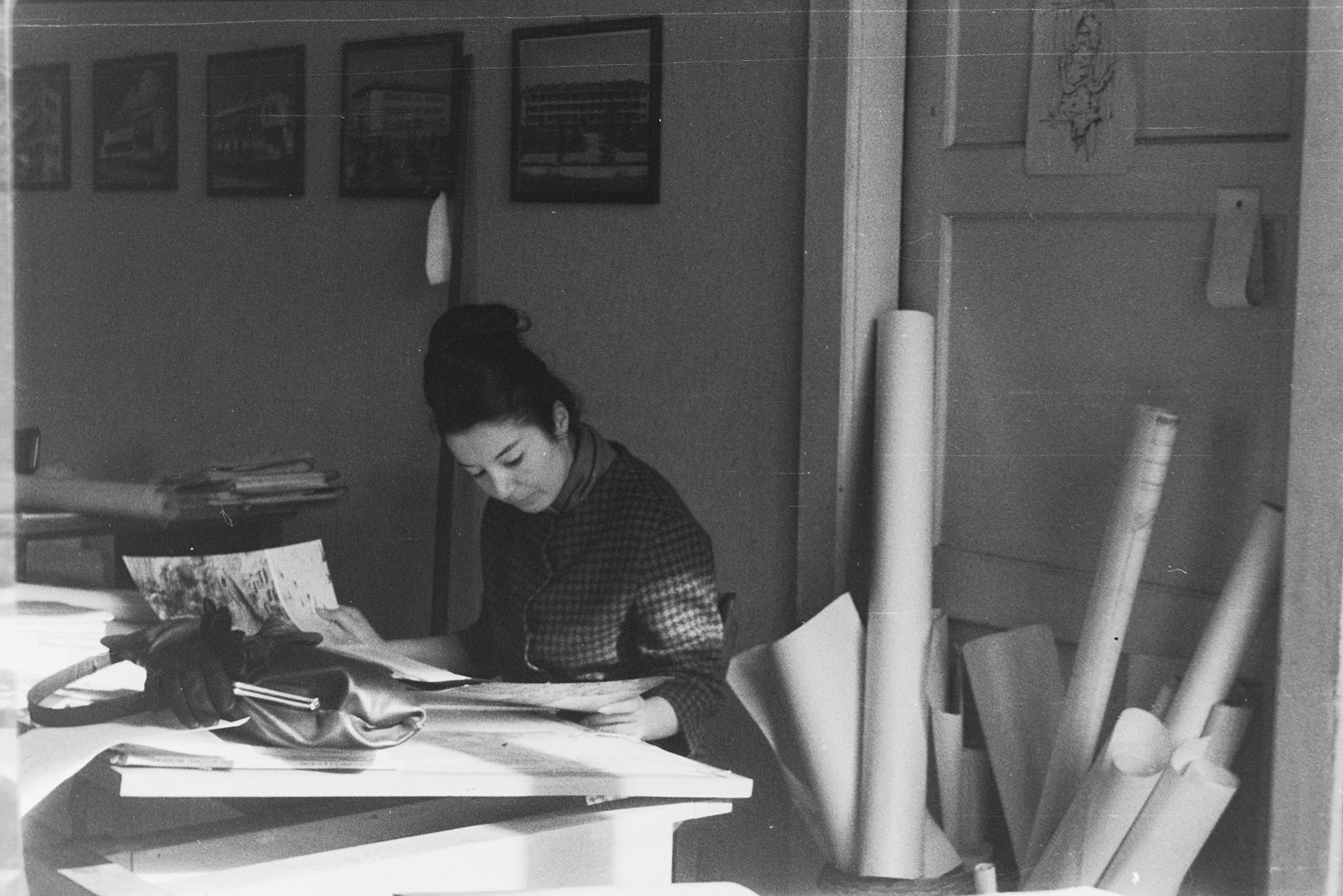

The Concrete Flowers of SVETLANA KANA RADEVIĆ

“LIKE A QUEER INSURGENT”: Slava Mogutin’s XXX Files

Architecture of Resistance: The Barricades of Kiev

THE AGE OF UNPEACE: MARK LEONARD Explains How Connectivity Causes Conflict – and How to Cope

FASHION DISSIDENCE: 16-Year-Old Ukrainian Photographer Shoots Protest Images in Kiev