IC3PEAK: "Not yelling is the most radical thing you can do"

|Cassidy George

Image: IC3PEAK

On a cold winter evening in Riga, I followed the secretive Russian musicians Anastasia Kreslina and Nikolay Kostylev of IC3PEAK down a treacherous set of stairs. Cold water dripped onto my head from the ceiling of a narrow, winding passageway, as the duo in matching track suits led me into a dining room of a candlelit, Medieval-themed restaurant, where meat hooks were repurposed as coat hangers and weapons hung as wall decorations. Just before a server dressed in historical garb approached to take our orders and distribute bread rolls that were individually wrapped in cheesecloth, Kostylev shared the tragic story of his pet bunny, Milu.

Milu managed to get himself stuck in a precarious and ultimately lethal position underneath furniture in Kostylev's apartment. After Milu was found, the musician rushed his bunny to the vet, who was unable to save him. “It could have been suicide,” Kostylev said. “Although I can’t really comment on his existential state at the time.” After we all shared our condolences and a moment of silence, Kreslina looked down at the menu and then back at me with her heterochromic eyes. “I'm still getting the rabbit,” she said.

Image: Sasha Komarova

Born out of Moscow’s mythologized witch house scene in 2013, IC3PEAK has spent the last decade engineering a constantly evolving take on gothic electronic, which has flirted with everything from folk and gore to hyper-pop and Gregorian chanting. Kostylev’s production choices are accentuated by Kreslina’s ethereal and adaptive voice, which has a piercing quality that is reminiscent of Björk, Grimes, and Portishead. In addition to producing an expansive discography, Kostilev and Kreslina have self-directed music videos with hundreds of millions of views and managed to make enemies of the Russian government, who have stalked, censored, and harassed them in response to their artistic critiques of the system.

In the top floor of an apartment building in Old Town, Kreslina and Kostylev opened up about Coming Home, an intimate new record that swaps political slogans for personal secrets, and social critique for tales of inner turmoil. Calling their widespread reputation as an overtly political band in question, Coming Home unfolds as a singular narrative that explores the feelings of love, longing, and displacement that have been exacerbated by war. IC3PEAK are known for being sparing with words, but I have never encountered two musicians with more to say. The only lull in conversation happened by force, when the obnoxiously loud bells across the street at St. Nicholas church rang for what felt like an eternity.

In what might be their most extensive English language interview to date, the duo spoke about the mechanics of their creative partnership, the complexity of Russian identity, and why they think Coming Home is their most radical project to date.

Image: Sasha Komarova

CASSIDY GEORGE: So why are we in Riga?

ANASTASIA KRESLINA: I'm originally from Latvia. I was born here, but I left at the age of six and I grew up in Moscow. I was not very culturally connected here, but I visited a lot and I’m learning a lot about Latvia now When the full scale war with Ukraine started, I left Russia completely. Riga is my base now ––but I haven’t been anywhere for more than two months in a row since the war started. I’ve been traveling and we’ve been touring. It’s not because I can’t stay in one place, it’s because I don’t really feel at home anywhere. It’s been a very turbulent period.

CG: That’s the broader theme on this record, right? The feeling of missing home or not knowing where your home is anymore.

AK: Exactly. Back in Russia I also felt pretty odd and not safe. I have been trying to rebuild... not my identity, because I never lost my identity. I did lose some ground, though, in searching for a home––whether home is a place or a person. Maybe I can also be my own home. One of the main themes I touch on is this painful feeling, this…

NIKOLAY KOSTYLEV: Longing.

CG: I think the album really encapsulates this yearning to be somewhere or with somebody.

AK: That’s the backstory. I was thinking a lot about wars and people like myself, who been divided from their friends and families and the places they used to live. At the same time, it’s a love story. I don’t know if I should talk about my personal life, but I’ve been in a relationship that was very distanced and difficult. There was that longing, and this attempt to connect the dots, but it was impossible. That was heartbreaking. All of these [influences] together formed into something that is musically quite different [from our past work].

NK: The lyrics also relate to me, but in a different way. I never felt at home anywhere. I didn’t feel at home in Russia and when I moved to Berlin, it was the same. We cannot go back to Russia because of our political past. Even though I never really liked it there, I started to experience this sense of longing for a home that I never had. Maybe it’s just my contrarian nature. I always wanted to leave. Now that I’ve left and can’t get in, I kind of want to go back!

AK: You’ve become much more sentimental about it.

NK: Even though I tried to push it away, I always had this Russianness in me, on a very deep level. The realization of who I am and where I come from has come to me slowly. Recently, I had a secular religious experience at an Orthodox church in Greece. I went in and saw such a beautiful ceremony. I felt that I was not really wanted there, but at the same time, I felt that I really belonged there. I was always an atheist and still am, that’s why it was a secular experience. But for years, these kinds of ceremonies were indoctrinated into me through things like funerals and weddings. In this church, I felt a real cultural belonging to my Russianness. This is translated into music in a far more abstract way than it is in the lyrics, because it's much harder to speak about these things in pure sonics.

AK: For someone who doesn’t believe in God, I go to church surprisingly often. It’s part of my culture and my early childhood, which I spent listening to my mom singing in an Orthodox choir. I feel a sense of familiarity and home within the church walls. It’s deeply coded within me.

Image: Valerie Dziatko

CG: The production has evolved a lot since Kiss of Death (2022). For a long time, you two represented a kind of generational dissatisfaction––but it seems like the ashes from the fire have settled, and your frustration has grown into something softer and more poetic.

AK: It's no longer time for slogans and statements. I used to be much more politically charged, more vocal, fierce, aggressive, and radical. I don’t think you can speak to people’s souls that way anymore because everyone is screaming from every corner. Everyone and everything is trying to make you pick a side. The world is very extreme. If you scream alongside it, you just dissolve into it. You lose yourself—you lose your voice.

NK: You become part of a choir.

AK: I think the quieter you are––the lower the volume that you speak––the more intimately and personally you can reach someone. It’s a very different tone of voice that allows you to talk about important things, like feelings and human life, your losses and your hurt.

CG: Nowadays, the more extreme you are, the more rewarded you get. I think this move towards delicacy is an incredibly apt way to continue your legacy of subversion into the 2020s.

AK: I think not yelling or picking a side is the most radical thing you can do right now. I’m not talking about extreme sides though, because of course there are things you cannot support.

NK: I think this also comes with age. When you read biographies, you can really see this progression. People generally become less extreme over the years. It’s not because they become softer, it’s because they no longer see the world as a single thing. You start to see more complexity and understand that there are many sides to issues. You begin to understand how much you don’t know. I think this is the main reason that we don’t speak in slogans anymore.

AK: Even the war is much harder for us to talk about now

NK: We were very deliberate with our message and it still stands, in terms of what we did, who we helped, and where we sent money. But we had to think it through really carefully and not to say too much.

CG: People take your messaging very seriously––does that kind of pressure and visibility also come with fear and hesitation?

NK: We are artists first. Anytime we want to do something that we think is cool, we want to do it immediately. We have this fire in our eyes and don't care at all until it's done. We unfortunately only start to think about the consequences later.

AK: We have always been bold. We realize now that many people in our position would be more careful, but we are very reactive. If we want to do something, we do it, and we are like that in our everyday lives as well. We immediately say what we think and it’s the same in our art. It would probably be smarter to be more strategic, but we are not designed that way.

NK: We are okay with dealing with the consequences.

AK: We’re also not running away from responsibility.

NK: It's worth the price of being chased out of the country! [Laughs]

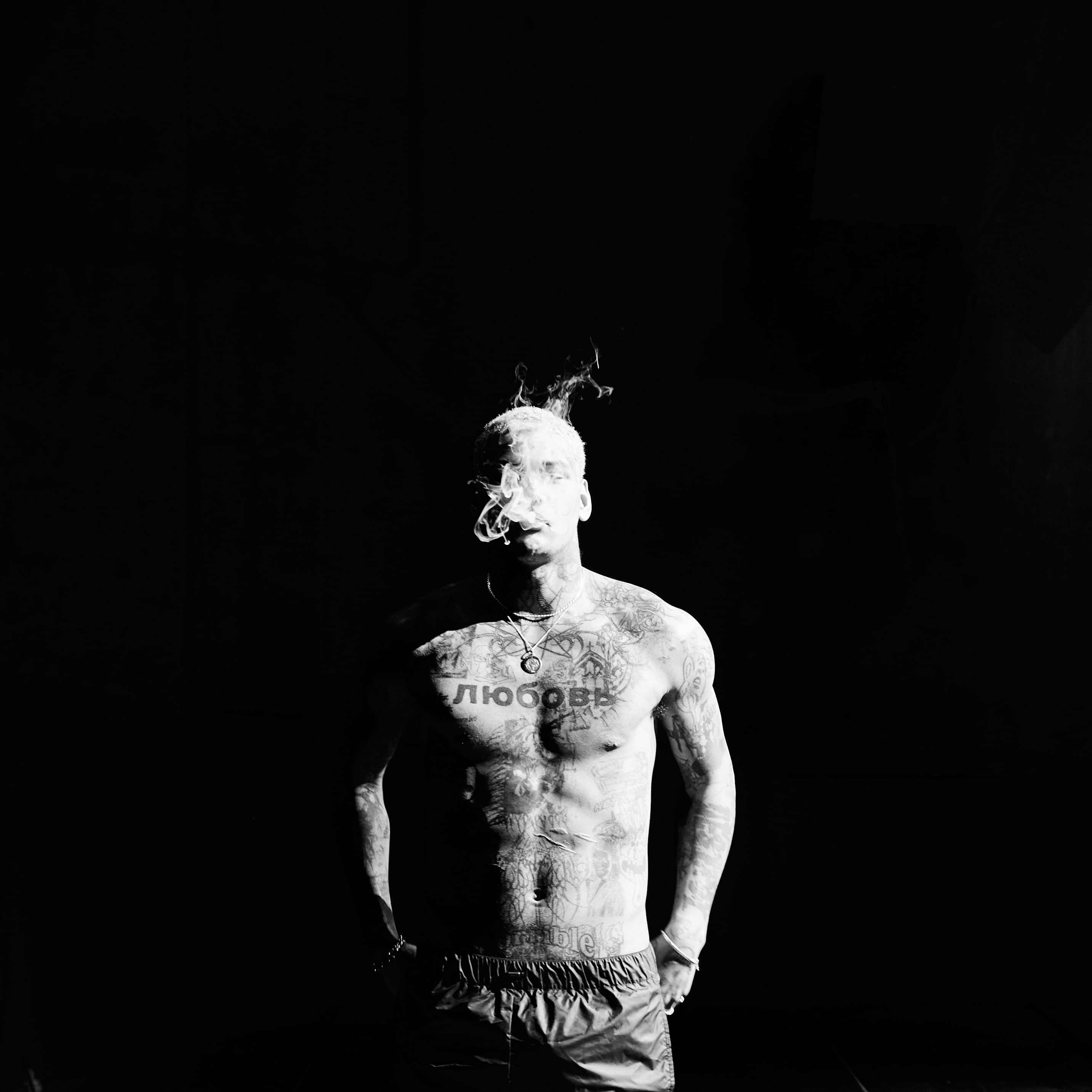

Image: IC3PEAK

CG: Your discography is not as overtly political as your artistic reputation. Do you feel like the role of politics in IC3PEAK has been exaggerated?

AK: We were never a super political band. It’s more like social commentary. The Russian government literally politicized us.

NK: The videos are one thing, but the songs are completely different and cover separate topics, often very personal things like relationships.

AK: For example, a lot of our songs are about abuse. It’s easy to draw parallels between a family system and country, both of which can be abusive. These themes are connected, but we never said: “The government is bad. Fuck you, Putin.” We said normal things about abnormal things that were happening around us. We spoke about what concerned us, but always in poetic form. This is very much in line with Russian tradition. In Soviet times, it was normal to discuss or criticize things in poetics. Many people who were in power at that time perceived poetic critique as a major treat. They censored it then and continue to censor it now because they believe that it is the starting point for everything else. And they are probably right.

NK: It’s interesting that poetry is more dangerous than direct messaging. It's more powerful because it penetrates deeper. We also make a lot of jokes in our videos. A joke can be more subversive than a statement because it passes through your defense mechanisms.

AK: Even if you don’t realize it, it gets stuck. It lives and grows with you, and you continue to think about it and open new meanings. Entertainment is very different. It has this fast and shocking effect, and then you forget about it.

NK: The more that we were pushed politically, the more people learned about us both in and outside of Russia. It was the best promo campaign.

AK: We always used to joke, “Thank you FSB for making us famous!” The FSB [Federal Security Service] is the extremist department that deals with things like us.

NK: We were a part of mainstream Russian culture for a couple of years. Although it might be more fitting to say that we were at the center of Russian counterculture for many years.

AK: So many things have happened since that chapter, though. Now we are in a kind of gray area because people don’t perceive us as Russian musicians anymore.

CG: Why is that?

NK: The last album was almost exclusively in English and didn’t really address a Russian audience. We also didn’t do any interviews or appear anywhere in the Russian media to promote it.

AK: We became so tired of it. From the moment that we started to be perceived as a political band, the only thing anyone wanted to talk to us about was politics, politics, politics. It was the same story every time––there were nothing innovative about the questions we were asked. We believe we are so much more than just politics.

NK: There’s a lot of Russian in the lyrics of this new album, so we are coming back to it, in a way.

AK: Although it isn't necessarily a social commentary, I think the core of this album is much more radical than anything we have done previously––due to this intimacy and closeness.

CG: I think a lot of people might be surprised to learn that you don’t have a label. It must be so nice to have the freedom to reinvent yourselves however and whenever you see fit.

NK: There were many moments in which we could have gone to a label, but we always decided to do it our own way––and we're so happy we did. When the war started, we had just dropped an album called Kiss of Death. Prior to that, we almost signed to a major label. If we had, the record would have been shelved for years. No one would have released that shit, 100 percent!

AK: We are proud of our independence. I think the only way we would get on a label is if we make our own.

NK: Labels are just banks, and we don’t need so much money for what we do.

AK: We put everything we earn back into what we do. We aren’t rappers, we don’t need golden chains. Neither of us come from wealthy families.

NK: We are really balling by our own standards, compared with 10 years ago!

AK: For us “balling” just means not struggling.

Image: Valerie Dziatko

CG: You have a huge catalogue of music but have only made a few music videos. How do you choose which song to make a video for?

NK: For me, it’s always a little bit of a schizophrenic process. On the hand, I have to believe I am doing it solely for myself. On the other, I have to believe I am doing it for everyone else. When those two things align––when I like it and think other people will too––that’s when it works.

AK: I feel it almost physically. Even when you write something yourself, you can always look at a story from a distance and see if it’s something that will translate well into a cinematic format. If a story is more abstract than it is concrete, then it will be more difficult to make the world of that story bigger with visuals. I love creating these worlds, even though it’s so exhausting and almost kills us every time.

NK: We are the actors but we also self-direct, so we’re playing all the major roles ourselves.

AK: This is extremely time consuming and very nerve wracking. You have to think about everything: your performance and how the shot looks. We're lucky that there are two of us because we can help each other. When we are both in the frame, it's difficult.

NK: I cannot say that I really like directing but I think we got quite good at it. I really do like editing though.

CG: My next question was going to be if you also handle post-production.

AK: We do the entire process ourselves. We just really love what we do, and we are control freaks. There's no other way to do it, especially if you want to get the exact result that you imagined. Of course some people do get involved. God bless them for surviving. [Laughs]

NK: Our shoots are intense. We change a lot of stuff in the process. It’s quite fluid.

AK: We also don’t have any education, so we are very intuitive. We freestyle.

NK: This has always been an audio-visual project. We wanted to create our own world, and we felt that the music video was the best medium for this. So in the beginning, we were hyper focused on making music videos. Now, when I listen to a lot of the music we made from the past, it sounds like music video music to me. You can hear how I would edit the video in post-production. I wanted this album to speak for itself. I also wanted it to be quite fractal. The deeper you look, the more you see, both sonically and lyrically. We didn’t think about music videos or how we wanted to present the songs until long after they were finished.

AK: Almost every song on this album is a story that could be visually supported. This is an extremely important aspect of the process for me because I started as a visual artist. Photography was my main field, and I always used to think of myself as an artist first. Even though I write, sing, and create vocal melodies, I didn’t think of myself as a musician for a long time. I had imposter syndrome because I don’t have any musical education. Neither does Nick, but we both come from musical families. My mom is an opera singer and Nick’s father is a conductor.

NK: And my mom is a piano professor at a conservatory.

CG: But you're a completely self-taught producer?

NK: My mom tried to make me learn piano, but I was really bad at math, and it is kind of like math. I would say that I really sucked at everything I did until I was like 14. I saw a photo of my dad playing the bass guitar and thought “I’m a musician now.” That’s how the child brain works, I guess. As soon as I became genuinely interested, it became a slow obsession. I got myself a dictaphone and started making musical instruments. But I’m a bad learner in the sense that I can never learn from someone else’s mistakes. I have to make them myself, which is why everything takes so long for me. But I think I can do unique stuff because my process involves a lot of trial and error.

CG: So you’re the baby that learns how to swim by being thrown into the pool?

NK: It’s so funny you say that because I recently started to surf. I know it’s not characteristic of our project, but I'm going to tell you about it anyway because I like it so much. I’ve been doing it off and on for about four years now, and I have been bad at it for four years. I cannot force myself to take lessons because I have to make every possible mistake on my own. I've gotten myself into so many dangerous and stupid situations because I believe I will always be okay. I still have lots of fun. I know I will never be a great surfer but that’s why it’s a hobby!

Image: Sasha Komarova

AK: I think this is also a very Russian way of doing things. No one really mentors you there. No one helps you or explains things to you. As a child, I used to call myself a “little grown up” because I did everything myself. If you learn this way, it sticks with you, and you grow to become very confident in what you do. The downside is that it's very difficult to teach others.

CG: How did you discover and hone your voice, then?

AK: Just through practice. I love to experiment. On every record I am wondering how I should entertain myself, so that the process doesn't become boring for me. On Kiss of Death, I started screaming and death growling. Even though I’m not super professional, it took me like a month to learn. It was so exciting and fun for me. In the future, I would love to reach more into the opera style. I’ve always dreamed of playing a role in an opera.

CG: Well, it’s in your blood.

AK: Probably, but it’s a huge challenge for me because I always compare myself with my mother, who is extremely skilled and talented.

CG: How well known is she? Have fans already made the connection between you two?

AK: She is not a mega superstar, but she has had a very big career. People have come to the theater that she works in and waited for her after shows to give her flowers and say that they’re fans of mine.

NK: [Laughs]

CG: I don’t know what kind of relationships you two have––

AK: She really likes what we do. All of it is funny to her, even though people showing up at her theater is kind of like stalking.

CG: Are you frequently stalked?

NK: We've had some weird interactions but overall our fans are much nicer than the Russian government! And there is only occasional weirdness because fans build unrealistic images of us in their heads.

AK: They literally write stories about us.

Nick: There’s fan fiction.

AK: Don’t read it.

CG: Well I can't, if it's in Russian.

NK: It’s in English.

CG: Great, then I'm definitely reading it.

AK: They’re mostly stories about how Nick and I would navigate an issue if we were in a romantic relationship. So, for us, it's impossible to read. Our core fan base is very supportive, though. They are one of the main reasons we succeeded in our story with the cops. They were messaging each other and came to the places we were playing in certain cities to support us.

NK: I remember they almost broke into a police station that we were detained in. This entire crowd started beating on the doors!

AK: It's no longer safe to do things like that in Russia, because everything is censored.

NK: It was a different time, a different place, a different country. Now, they would all be in jail.

CG: It’s mind blowing to think about how much transformation one place can undergo in the span of a century. You, your parents, and your grandparents all have known such different nations, despite being from the same place.

NK: As far back as you look, almost every generation in Russia has gone through an extremely traumatic experience. My mother was a professor at a university when the Soviet Union collapsed. The next thing she knew, she was selling things on the street in Moscow while raising two kids. My grandmother lived through an extremely impoverished, post-war Russia, which had been ransacked by Nazis––as well as the Soviets. This was the time when many people were taken to Stalin's camps. It’s a historically tragic place.

AK: Some Russians say that we have trauma in our DNA. I don’t believe that, but I can relate to the image metaphorically. My mom is rebuilding her family tree. It's amazing how many of my family members managed to survive and be happy, despite how difficult life was. This is what gives you the hope to go on. For the first few years that we were in Moscow in the late 90s - 2000s, seven of us lived together in one not very big flat––but we felt so lucky to even have a place to live. I think we are a good example that you can make something from nothing if you really want to.

NK: We emerged in a period where things were getting better and better—until they got worse. It was a unique historical period of economic growth.

AK: It was a window of freedom, I would say.

NK: The last time that happened was the beginning of the 20th century. We were extremely lucky to have experienced freedom. That’s why there was also this genuine rebellion in us when we noticed things starting to change.

AK: We thought we could do whatever we wanted because we hadn’t seen real oppression yet. Our parents, on the other hand, are much more careful because they saw how terrible it could be. Now, we have a better understanding.

NK: Now the oppression is getting back to pre-Khrushchev levels, politically.

CG: When compared with other nations and societies that we associate with complex historical trauma, my feeling is that Russians rarely speak about their suffering. They are quiet about it.

AK: It’s not in our nature to complain. In the Orthodox religion, you have to suffer in order to gain a better afterlife. Through suffering, you learn and gain permission to be yourself. Only then will God give you everything. The idea is that because God himself suffered, you must too. This is completely normal in our culture.

NK: After the war started, I started reading Russian history. I learned a ton about Stalin, Lenin, and the revolution, and it’s very reminiscent to me of what’s going on now––Stalinism, in particular. It's this emergent phenomenon that is self-organizing. It almost feels determined to happen again and again, because of geography, because of history, and because of the way the system is shaped. It’s all one big circle.

Credits

- Text: Cassidy George