Screentime Overload with Eugene Kotlyarenko

|ARIANNA CASERTA

In his book The Crisis of Narration (2024), South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes that “reality itself takes on the form of information and data” in today’s digitally mediated world. The paranoid visual overload of messages, push notifications, and social media prompts that crowd our daily lives have been director Eugene Kotlyarenko’s signature style for a decade.

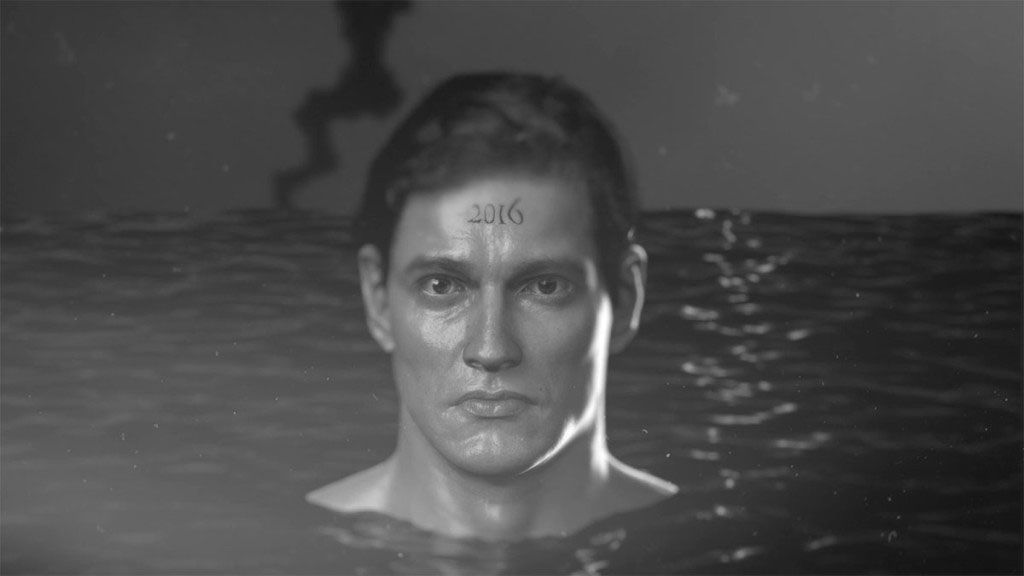

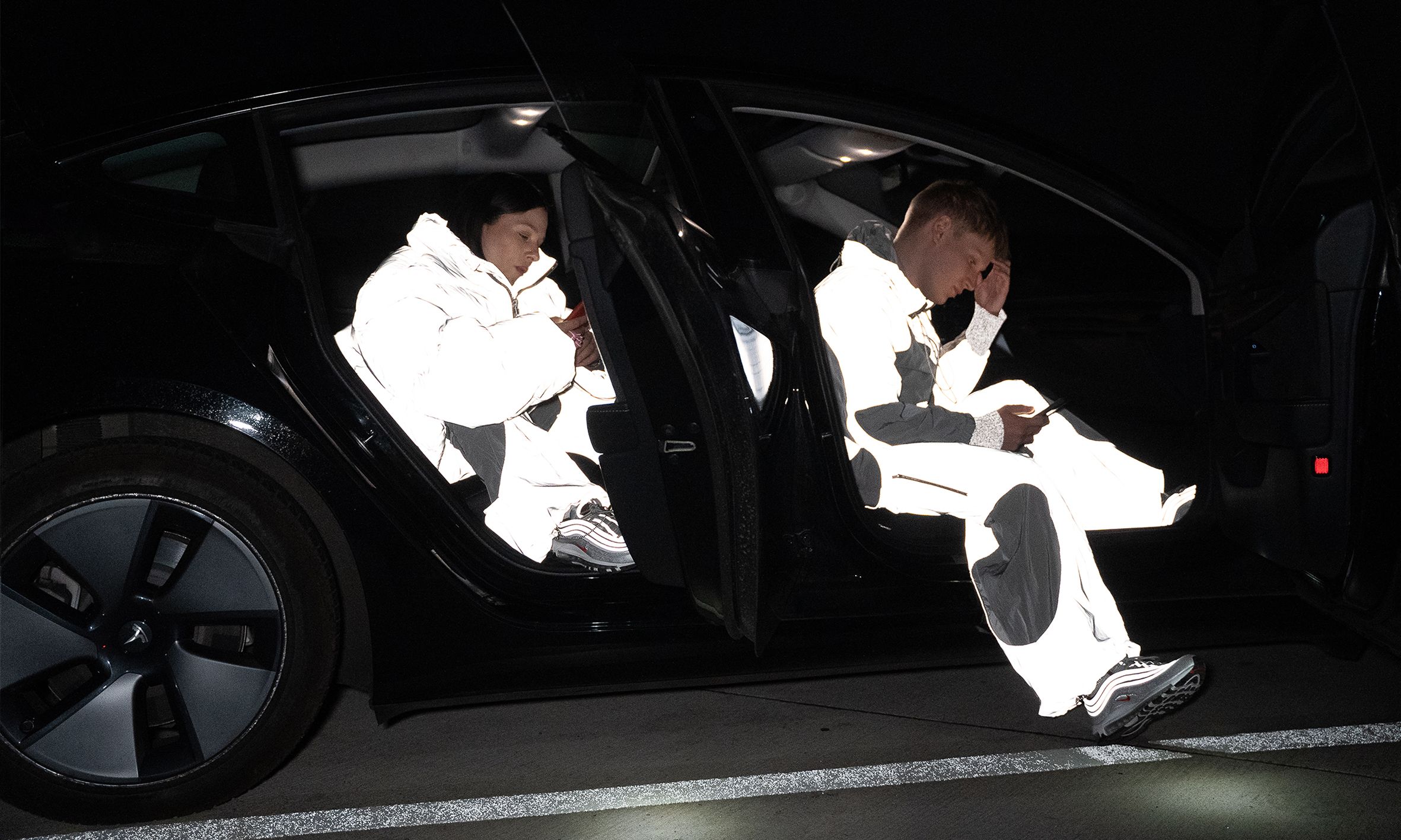

Still from The Code, 2024, featuring actors Dasha Nekrasova and Peter Vack.

With films such as 0s and 1s (2011) and Skydiver (2010), he has helped the film genre “Desktop Cinema” become what it is today: a true depiction of how our everyday life has been mutated by interfaces, giving birth to a new sensitivity.

This year, the director’s new film The Code premiered at Fantasia Film Festival in Montreal. Investigating social media, surveillance, and our ways of identity building through cameras, the film stars a chronically online power couple—the Red Scare podcaster, actress, and director Dasha Nekrasova and director, actor, and meme-account admin Peter Vack—who are obsessed with the idea of being cancelled on the internet. Filmed through a welter of different devices such as spy glasses, camcorders, and CCTVs, The Code is a visual essay about how the internet re-shaped our intimacy. Through each frame, The Code makes us feel like we're watching the characters' stories through a crowded desktop, continuously disturbed by spam and multi-tabs accumulating.

ARIANNA CASERTA: Can you tell us about the writing process and the first images that popped into your mind for The Code?

EUGENE KOTLYARENKO: 19 years ago, before I ever made a feature, I read a book called The Key, about a married couple who keeps diaries. It’s by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, one of the great Japanese authors of the 20th century, very inventive and naughty. The structure of the book alternates between the diary entries of the husband and those of the wife, portraying different versions of the same events. Then, halfway through the book, they suspect the other person is reading their private thoughts and so they begin writing performatively. At that point, you as a reader cannot understand if what you’re reading is an honest picture of reality or a falsified account for the other person’s gaze. Ever since then, I’ve wondered: how could I make a movie that captures this spirit? That is, a story about a couple battling for narrative control? For decades I’ve considered whether the movie could revolve around hidden blog posts, secret YouTube accounts, finstas, and other dead-end ideas. I kept kicking this project down the road as other movies materialized, but during the lockdown I saw how couples were stuck together in a forced psychosis, and I knew I had to finally make this film.

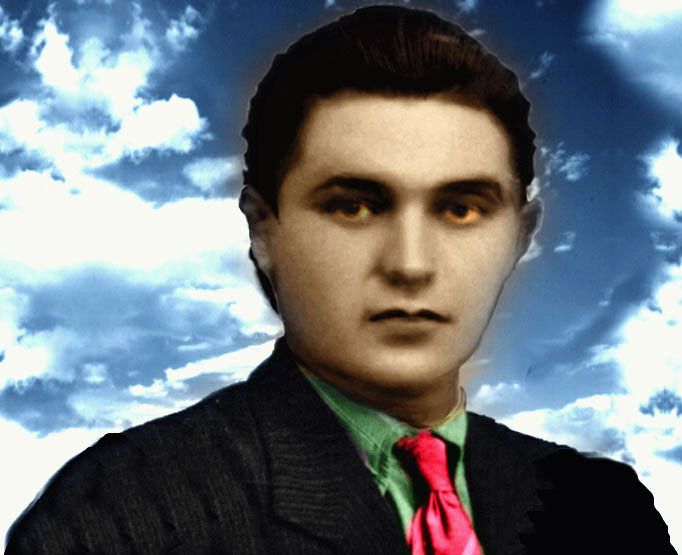

Eugene Kotlyarenko in A Wonderful Cloud, (2015).

AC: You published the sheets that helped you keep track of the many cameras you used to shoot the film, and they looked absolutely crazy.

EK: I was going through promo images and something as mundane as that spreadsheet suddenly looked beautiful to me, so I posted it to my story. We used 75 cameras, because the grammar of the movie expands during its runtime: it starts off with a handheld camera, and then it grows into this maximalist thing with surveillance cameras, spy glasses, and more. That document was useful to keep track of the cameras on a logistical level, but also to think about the intentionality of the use of so many cameras and its aesthetic purpose.

AC: Unlike the book, the characters in your film are also aware of us, the spectators, and they’re scared of what we might think about them. They know there’s a Big Other who’s going to judge them.

EK: Yeah, the whole film is about performativity as control. There’s no real privacy anymore. Even a private feed lives on a server somewhere and could become public at some point. Even if a message is meant for a single person, you know that it can be decontextualized and then incorporated into something very public. Before, people were much more comfortable trusting someone to utilize their image or persona in film. Now that we’re all brand managers, there’s a lot of anxiety about letting someone else manipulate your persona in their work.

AC: It’s very fun how, in the movie, we get to know the truth about your characters through the use of their phones. It subverts the idea that social media is a filter that disguises “reality.”

EK: Well, that was a big part of the film from the very beginning. The big question was: what happens when you look through your partner’s phone? If you suddenly had the code to their phone, would you take a peek inside? Is that a good idea? It’s like Pandora’s Box. Once you open it, you’re inevitably unleashing knowledge you’ll never be able to unsee. Even in the most transparent relationships, there’s a certain interiority and privacy that we need within ourselves.

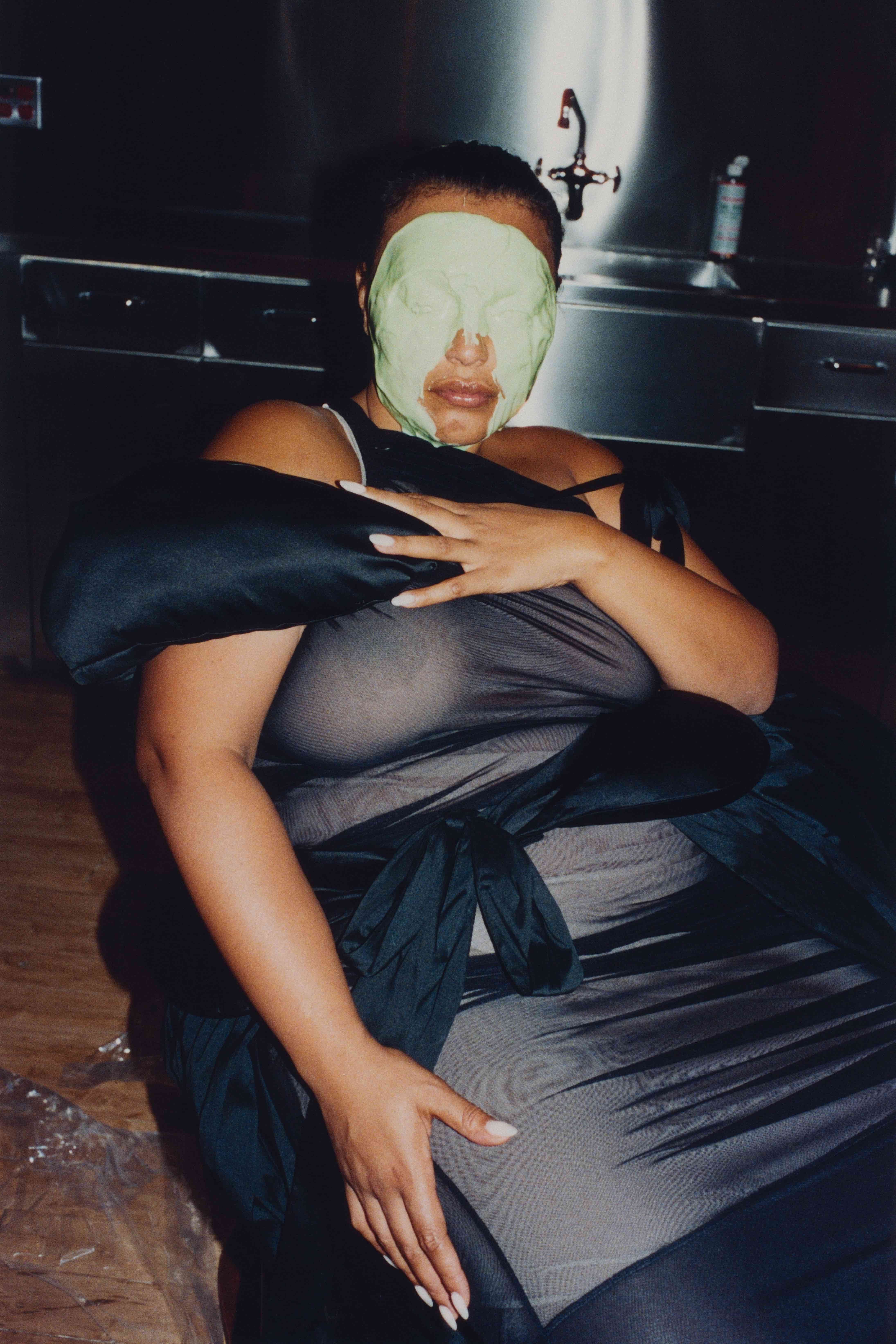

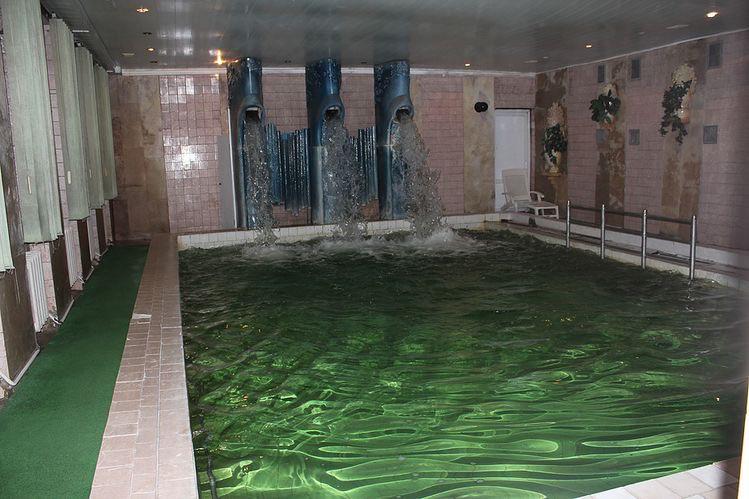

Still from The Code, 2024, featuring leading actress Dasha Nekrasova.

AC: In The Code, you also decided to pay homage to Ryan Trecartin’s films, with a character producing a video that looks exactly like I-Be-Area (2007) or Center Jenny (2013).

EK: I actually called Ryan and asked him if he wanted to help me make this homage to him with a bunch of college students, but he said that he was really busy and couldn’t. But I was happy I got his blessing.

AC: You have the Trecartin homage, and then the soundtrack was made by Dylan Brady. I see both of these artists as two icons of brain rot internet culture, whether it’s Ryan predicting TikTok’s maximalist visual style or hyperpop doing that in music. I don’t know if I can think about an equivalent in traditional cinema.

EK: You know, generally speaking, cinema can be the last in the culture to access things, especially popular cinema. On the other hand, there were maximalist experiments in cinema that spoke to me as a film lover. One of the first pieces of media that I was obsessed with was the trailer for A Clockwork Orange, which is one minute long with like 200 cuts in it. There were highly creative montages by Slavko Vorkapić in the 30s. Whole sequences and swaths of Soviet Cinema with a hyper-kinetic style. Recently, it was Tony Scott and some others. There’s a lot of artists I relate to who are speaking a language similar to mine: Ryan, Jon Rafman, or even someone like Sam Hyde.

Movie poster for The Code, 2024, directed by Eugene Kotlyarenko.

AC: For years now, directors have tried experimenting with different ways of implementing chat rooms and online conversations in movies. What I noticed is that sometimes it looks very off or doesn’t really match with the storytelling. But not in your movie.

EK: The most popular way nowadays is to put a text message over someone’s head or something like that. From my side, I do it often with the split screen. If we’re in a Zoom call like now, I can process both of our faces at the same time, just like you can process a notification banner while writing a message and listening to a song. Because we’ve been rewired to process so many things at once, it’s impossible to overwhelm people. I’ve always been interested in having those things up on the screen at the same time, so that a person can do the montage in their head.

AC: I guess that the split screen is the visual strategy that more resembles the actual way we receive these stimuli.

EK: Yes, and it also plays with the historical role of voyeurism in cinema. Maybe I’m a bad person, but when I’m on the train or waiting in line, my favorite thing in the world is to sneakily look at people’s phones while they’re messaging or playing games. It gives me great joy. And so, for this movie, I wanted to conjure the privilege of accessing someone’s secret life in a new way. Voyeurism is such an incredible and weird gift.

AC: Then, in the film credits, there’s this joke where Peter’s character, Jay, wants to hop on the credit list to say that he had a role in making the movie. It’s great because it matches the main theme, which is this fight for who’s going to be the real author of the story.

EK: I thought about the credits years before I shot. Initially, I thought they were going to be passwords and CAPTCHAs, all these kinds of secret codes that run through our lives. But when the edit was done, I changed it into something a bit more playful. They go back to the central question of who’s in control of the narrative, who is going to get the credits for the story. But it’s an important question for culture at large: who’s in control of the dominant narrative? Before, you had hegemonic media, and everybody pretty much agreed on what was happening in reality. When you decentralize the sources of information, you get all of these people accusing the others of publishing fake news. But there is no fake news. There is just no centralized narrative.

Still from The Code, 2024, featuring leading actress Dasha Nekrasova.

AC: I think that new generations won’t be interested in truth as much as older ones.

EK: It’s a very schizoid thing. In order for a society to coherently function, you need a central narrative, a type of mythology that everyone can subscribe to. When it fails, you get a nihilistic and confusing culture. But that’s also what was cool about early social media: it took away authority from traditional media and put it in the hands of normal people. Suddenly, marginalized groups and oppressed voices could finally speak out and center their experiences. At that point, it has become undeniable that “the truth” is much more subjective than we think.

Credits

- Text: ARIANNA CASERTA

Related Content

All Networks Lead Through Kansas: The Shadowy Well(ness) of Masculinity

Where Does The Puppet End And The Human Begin?

“We Cannot Assume False Neutrality”: Wu Ming—from the Luther Blissett community

Hajime Sorayama: What I Draw Are Human Beings

What Future Do We Crave?: KATHARINA KORBJUHN’s Paradigm Trilogy

KRISTINA NAGEL’s Landscapes of Depersonalizations

An Analysis of The Backrooms—Also Known as the Internet's Horror Rooms

Julian Charrière: Ancient Reefs and Active Volcanoes

Brutalismus 3000: “The Secret Ingredient is Controversy”

Who Wants to Be a Human Jukebox? Richie Hawtin

The New American Dream Is Sponsored by Meta: ANA VIKTORIA DZINIC

Weaponized Irony: A Roundtable on Trolling and Politics