Be Careful What You Wish For: Gakuryū Ishii and Masatoshi Nagase

|Phillip Pyle

Those who obsess over the Box Man become the Box Man. Or in other words, be careful what you wish for since you just might get it.

In celebration of the Japanese writer Kōbō Abe (1924–1993), who would have turned 100 in 2024, we are publishing a feature on Gakuryū’s Ishii’s The Box Man, a film adaptation of Abe’s 1973 novel which premiered earlier this year at the 74th Berlinale.

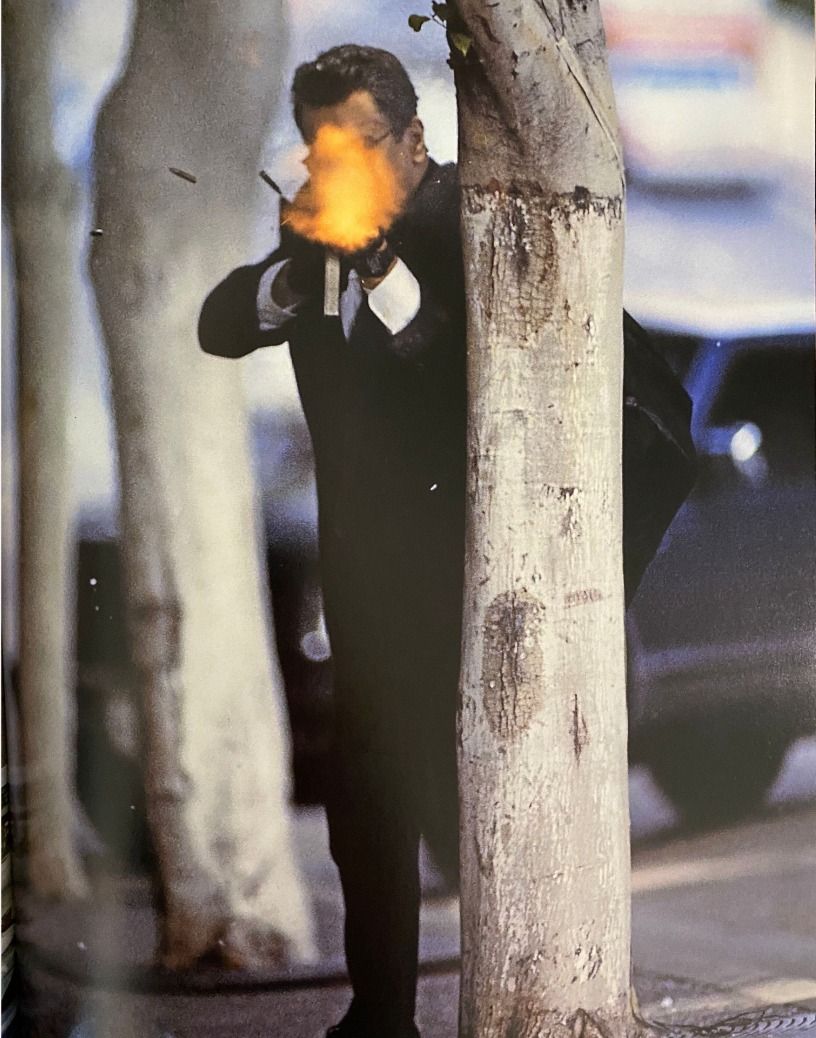

Still from The Box Man

For Jean-François Lyotard, the postmodern could be boiled down to a skepticism of grand narratives. He writes, “Lamenting the ‘loss of meaning’ in postmodernity boils down to mourning the fact that knowledge is no longer principally narrative.” In this computer age, where advances in technology, science, and communication systems normalize information as the default carrier of knowledge, the individual subject especially falters with the demise of narrative knowledge. After all, even personal biography suffers from this condition, for the postmodern displaces that which was previously most precious to identity formation: origins.

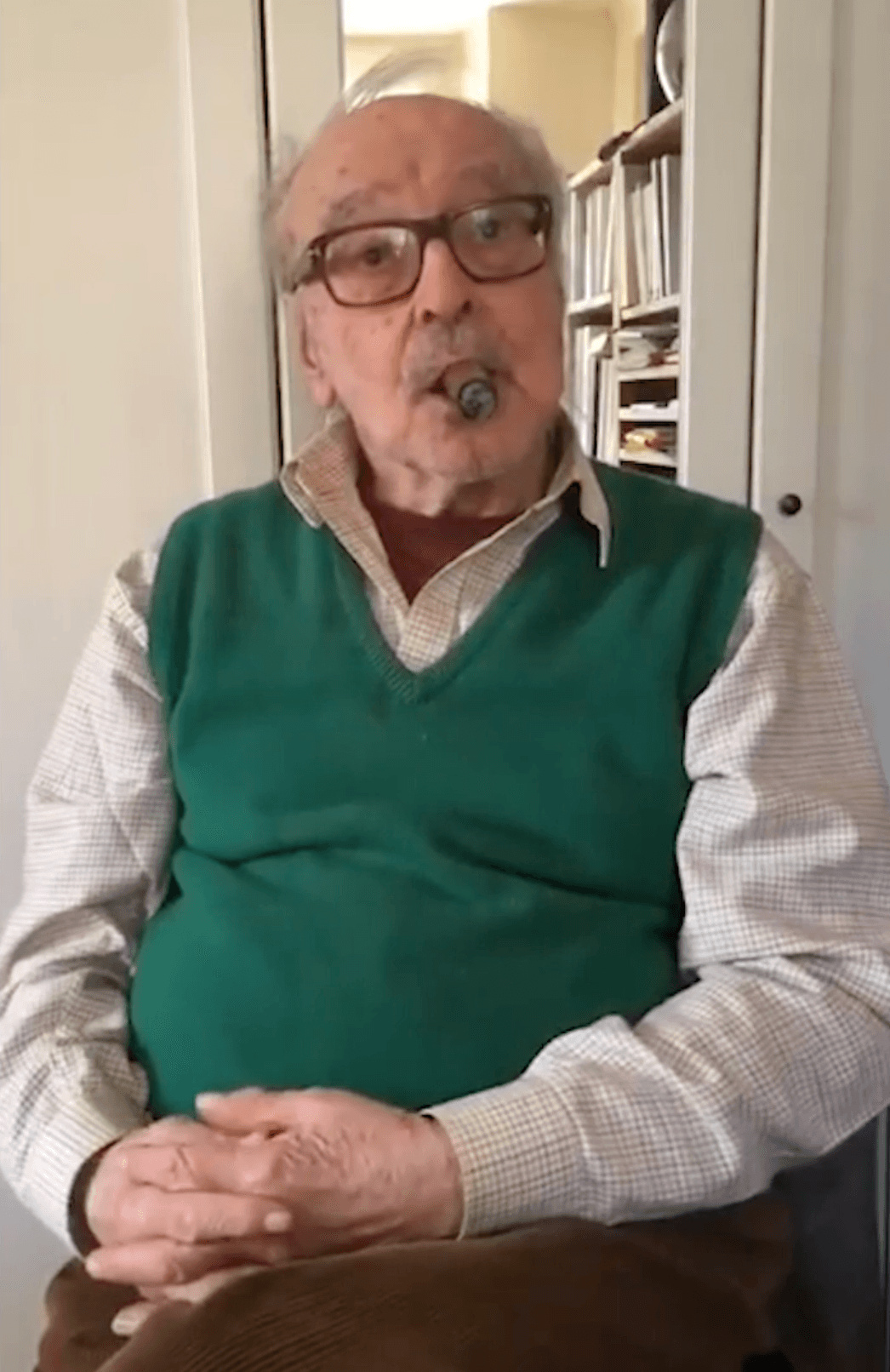

Gakuryū Ishii and Masatoshi Nagase

The Japanese writer, playwright, and theater director Kōbō Abe often dealt with these concerns years prior to the publishing of Lyotard’s 1979 classic The Postmodern Condition. From early on, Abe was intimately familiar with displaced origins. Born in Tokyo in 1924, Abe came of age in Manchuria when it was under Japanese colonial control. Later moving to the island of Hokkaido, where his mother grew up, before returning to Tokyo for high school, Abe’s early life was defined by a series of incoherent origin stories—the sum of which would lead him to later describe himself as both a “man with no hometown” and one who does “not identify with any fixed placed.” Abe’s lack of interest in providing readers or audiences with single origins is especially evident in his 1973 novel, The Box Man.

The book centers around the narration of a nameless man who introduces himself as the box man. However, the box man whom he discusses throughout is not himself or a single, other box man but instead a synthesis of a series of different men or “cases,” as he describes them, whose encounters with other box men occasioned their own transformations. In “The Case of A,” for instance, the narrator describes a man who became so obsessed with another man who wears a cardboard box and resides beneath his window that he, too, began wearing a cardboard box. The result is a frenetic and urgent reflection on identity, perception, and disaffection amidst the burgeoning information age. Abe’s novel, which celebrated the 50th anniversary of its translation into English this year, is already tinged with the familiar fractured narratives, shifting prose, and inconsistent points of view of postmodern writing. But it is the chameleon-like filmmaker Gakuryū Ishii’s film adaptation of The Box Man, which premiered earlier this year in the Special section of the 74th Berlinale, which realizes the story’s spectacular potential.

The origins of Ishii’s adaptation are somewhat murky. Ishii first gained approval to adapt the film over three decades ago from Abe himself, just before the writer died in 1993. Coming on the tail end of cyberpunk’s explosion in the 1980s—a genre which Ishii has often been credited with engendering through his bridging of punk subcultures and cinema with his first feature films including Panic High School (1978), Crazy Thunder Road (1980), and Burst City (1982)—the filmmaker’s embrace of Abe seemed fitting at a time when his style was gravitating toward more poetic and opaque narrative. In 1997, just one day before the production was set to commence shooting in Hamburg, an issue with financing arose.

Eventually, the thread was picked back up. However, some changes were needed. Ishii and co-writer Kiyotaka Inagaki rewrote the screenplay, setting the film in the present. The adaptation retained the novel’s core, centering on the intimate yet emotionally distant set of relations surrounding a titular box man. During our conversation at Silent Green in Wedding prior to the premiere, Ishii assured me that even this choice was in dialogue with the past. “This film is starting from that time and continuing until this time,” he said. “So, there’s a continuation from that time until now.”

In the film, though, the paranoia, repression, isolation, and perversity first explored by Abe as emergent feelings in the mid- to late-20th century are colored by the omnipresent, normative status of those very same feelings today. The titular box man, played by actor Masatoshi Nagase—My Sons (1991), Mystery Train (1989), Patterson (2016)—is no longer a far-fetched character. Instead, the photographer-turned-box man, who spends his days scrawling notes, drawing impressions, and photographing that which comes through his limited window slit, is not a far cry from what we consider to be incels today. The fact that he actively attempts to avoid romance and sex only makes the comparison more fitting. However, insofar as Ishii (taking a cue from Abe) equally presents the undue violence, unrelenting objectification, and overwhelming stimuli that the box man faces, the film also uncovers the vicious cycle of self-protection and projecting insecurity that produces such subjects.

Interestingly, those who attempt to coax the box man out of his self-willed isolation are portrayed as being the most violent. The box man is shot, physically assaulted, and met with constant judgment merely because of his imperceptible, and thus incomprehensible, form in the eyes of onlookers. And in a projective turn, it is such violent men who most want to become him—in much the same way that Nagase’s character, who is not the “real” or original box man, was voyeuristically preoccupied with another box man before becoming one himself. He later becomes an object of study for a small medical practice operating out of a rundown Tokyo hospital. The general doctor, played by Kōichi Satō, and his unqualified assistant, played by Tadanobu Asano, become preoccupied with the box man in a typically repressed, hypermasculine way; that is, to the point where voyeurism morphs into outright violence, insanity, and eventually mimicry. The practice’s nurse Yoko, played by Ayana Shiramoto, occupies a more ambiguous relation to the box man. At once the object of his latent desires, the threat to his celibate facade, and the only character seemingly uninterested in living her own life under a cardboard box, Yoko is the film’s closest approximation to what it means to be a discerning subject today.

Unlike the film’s male characters, whose solipsistic ramblings and megalomaniacal obsessions with box men ignore a key facet of their identity solution, which is that they are no longer masters of an already-splintered postmodern language, Yoko’s more sparse dialogue and pensive disposition make her character’s mode of judgment distinctly aesthetic. Lyotard calls for this aesthetic turn in The Postmodern Condition, advocating for a more “reflective” judgment that does not seek to denotate and unify knowledge, as language necessarily does, but instead moves deftly amongst the various irrational conditions that one is faced with. Yoko achieves this by remaining open yet reticent, a figure at once affected by and somewhat visibly apathetic toward the box man’s plight.

In our conversation, Ishii linked the identity dissolution at the heart of The Box Man to his own relationship with photography. His experience making the film underscored the widely felt disintegration of subject and object categories that the role of the photographer had previously masked. “27 years ago, I just started taking photos because of the film,” he says. “At that time, I felt there was no difference between the subject and object, in terms of authority.” While he sees this as sometimes being a positive thing, The Box Man explores the opposite direction. “We describe the negative side of the craftsman as being frantic and aggressive.” Nagase’s method performance as both an anxious watched figure and an objectifying voyeur makes this excruciatingly clear. “I obviously first did this 27 years ago,” Nagase says. “But I was actively inside the box for a month before shooting this time as well.”

The Box Man ends by revealing a cinema audience as the ultimate box man, instantly decimating the typical audience-film separation and thus extending the implications of its diagnosis. The conflation is urgent, in that it suggests that no one is exempt from the conditions which catalyze our becoming pariahs, yet still highly relative. “It’s a meditation for people who are seeing or making films,” Ishii says. Gakuryū Ishii’s adaptation is auto-fictional in this way, but in a quintessentially postmodern mode, containing the mark of his own life’s practice and that of Abe’s.

Credits

- Text: Phillip Pyle

- Photography: Alma Leandra

Related Content

MANN’s World

DEAR JEAN-LUC GODARD

I STILL LIKE TO MOW IT ALL DOWN: Harmony Korine

An Innocent Mind Has No Fear: the Movie

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY’s DUNE is the Most Influential Movie Never Made

More Politicians Should Be Artists / More Artists Should Be Political: Take Note from Albanian Prime Minister EDI RAMA

BEDA ACHERMANN: Portrait of a Swiss Art Director

Black is a Hard Drug: ODILE DECQ

BRANDING BHUTAN