MANN’s World

To commemorate the 28th anniversary of the acclaimed film Heat (1995), a feature on the director, Michael Mann. As seen in 032c Issue #40.

The films of Michael Mann are relatable even at their most improbable, human at their most wild – perhaps because Mann is a filmmaker who makes himself. His influential Heat, (1995) was a reprisal of his own L. A. Takedown (1989), itself an unsuccessful pilot salvaged as TV movie.

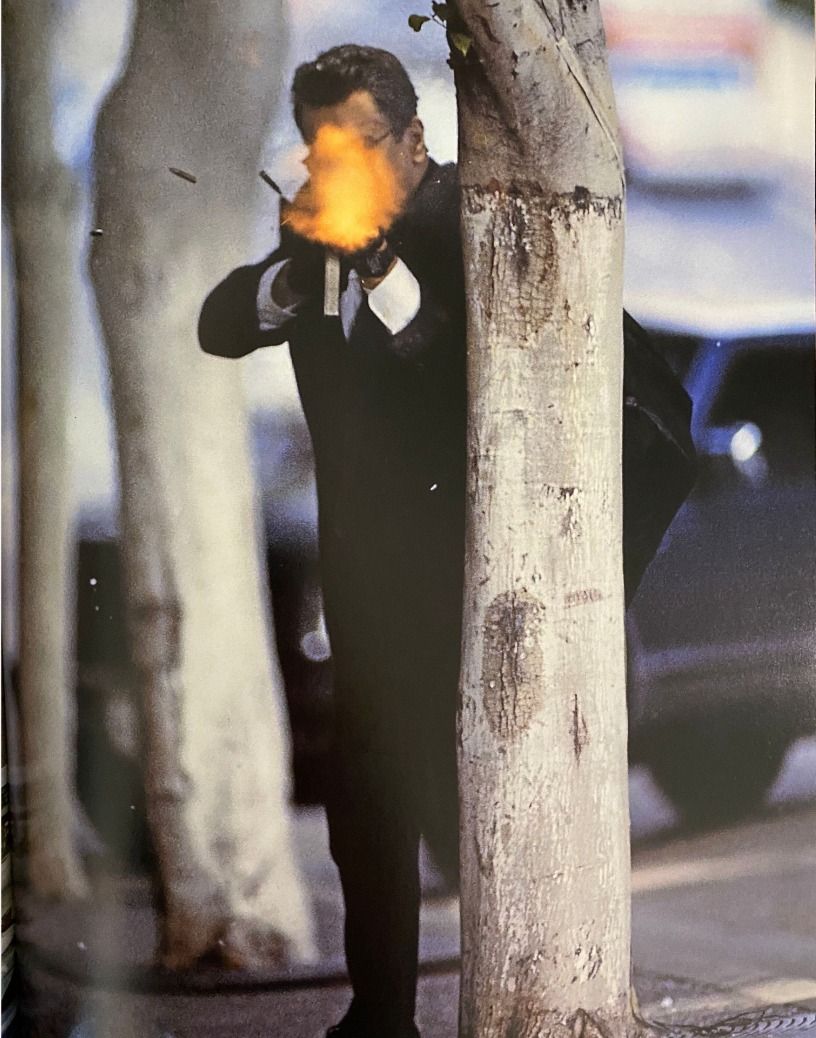

Heat’s reception among critics was explosive, as it was among criminals, inspiring actual bank robbers to plan heists in its image. Mann’s work has a way of bleeding into our reality, despite the scope of his sagas, the mythic quality of his trademarks – the immersive soundtracks, the agony of hard decisions made overlooking the sea. The cobalt lens through which he filters the emotional experience of his characters is the blue light of the smartphone and tablet screens through which we see and feel the world.

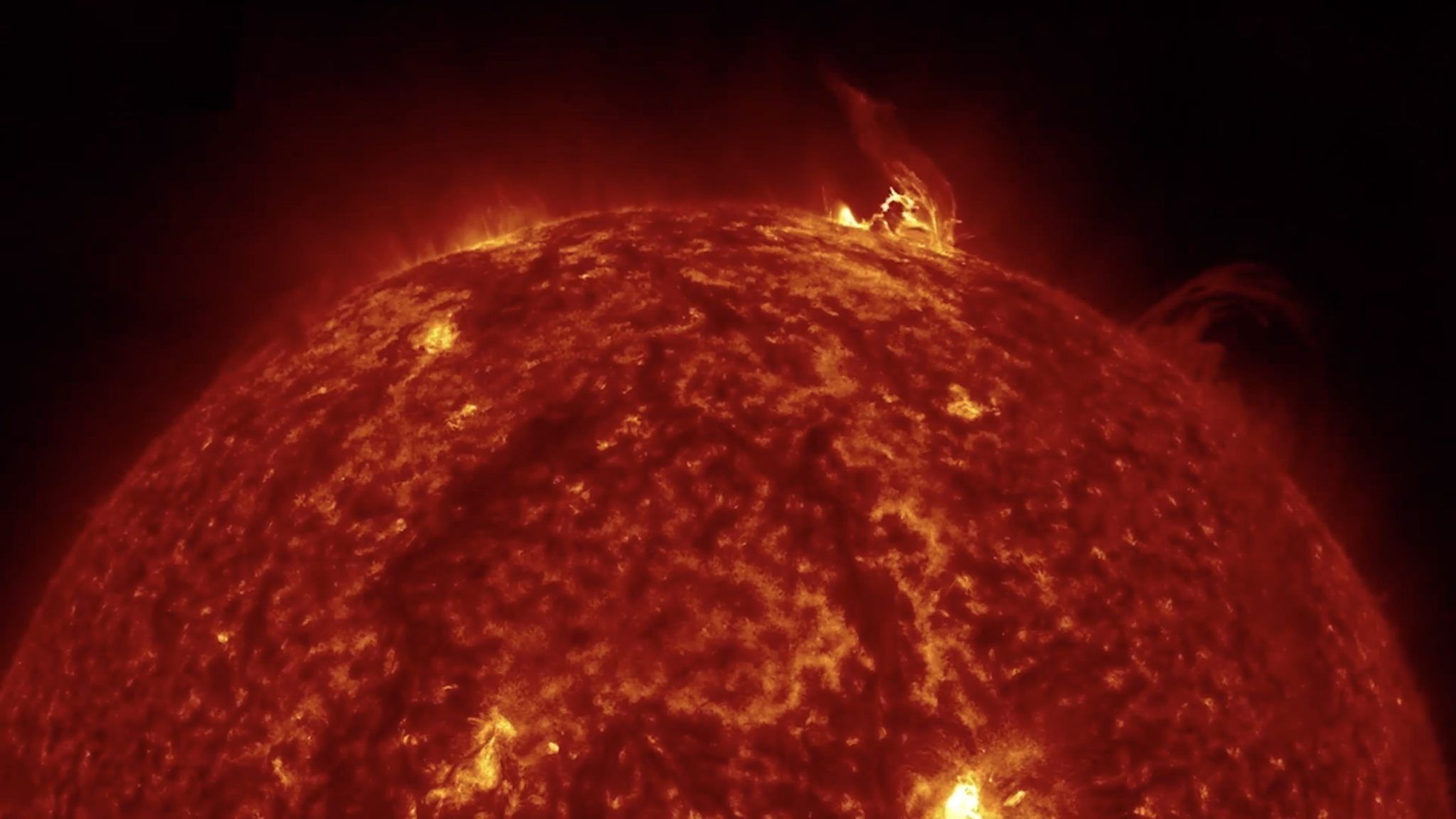

1. In the world of Michael Mann, the blue hour lives in an unfurnished glass box on the beach. It wears a gray suit. It paces back and forth as if patrolling the deck of a ship. It is a twilight blue, an indigo – the blue of melancholia and aporia, of unexpressed longing and failure. “The heaven tree hung with humid night blue fruit,” a sleepless poet said nearly a century ago, and this blue emerged fully formed, modern alienation incarnate.

Blue appeared on the peripheries of the early modern novel, in the nocturnes that played from the small windows of attics. It was the light in a literature of insignificant, private journeys: a 200-page search around a city to find a cigarette; a wealthy, indolent man who locks himself in a room and falls into a state of aristocratic desuetude for the rest of his life; and a family trampled by the interwar period in the shadow of a lighthouse, each of its members left to themselves, trapped in themselves, and far from one another. Blue was a state of self-imposed exile, a struggle to write untranslatable feelings in a second or third language, at a time when the city was a monastery for atheists and the home, a cell.

Shortly thereafter, and without warning, blue silvered into the chiaroscuro of film noir. It went incognito. It became a colorless light in Howard Hawks and Nicholas Ray, Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock. Blue was a tone, a radiation that certain male characters emitted as they navigated the labyrinths of the city, an animal glow set against the golden nimbus of Marlene Dietrich and Lauren Bacall. It was there in the slow blue nights of port cities and small border towns, the tropical noir of way stations in Key West and Casablanca; in the crossroads, hallways, prison cells, and nightclubs; in the lamplight of a desolate lot under an overpass; in the spotlight on a pay phone on the roof of a parking garage (and the hotel room visible from it); in the good sex, forgotten and remembered as bad sex; and in the lovers in a small kitchen lit by the neon sign across the street, sharing cigarettes in familiar silence, unable to say what they mean.

Blue appeared in the Swedish chamber dramas of Ingmar Bergman, where the blue hour feels infinite and a blue sun sets listlessly in a blue sea. Blue is the sad undertow in Jean Renoir and Max Ophüls, a longing for a world before film; it is the fête galante and the music hall, the weekends in the country, the servants, the brothel, the pomp and formality of the world before the wars. Blue was in Japan too – in Mizoguchi and Ozu – in those slow, ambling shots of figures navigating a penumbral world, the camera lingering long after a scene ends on a passing ship seen through an open window or the shadow of a rustling tree cast across the floor.

At some point, after the war perhaps, blue started feeling itself. What began as an indeterminate urge, an erotic charge, ossified into the high orthodoxy of midcentury existentialism, the dinner party assholery of the Boulevard St. Germain set. It transformed into ecclesiastical doubt disguised as fashionable pessimism, bad coffee shop poetry, and the self-flagellating pieties of Graham Greene – the ersatz philosophical crises of the career spy. Blue sobered up; it stopped sad fucking and slept eight hours a night. It earned a degree, changed colors, won awards, and got the girl. After all, this was too specific a shade to render in the saturated world of Technicolor.

Then, three decades later, just as the 20th century began sleepwalking to its end, blue burst into full fluorescence in the neonoirs of Michael Mann, settled like a miasma over the lonelier stretches of Los Angeles –the 24-hour diners, the rooftops, the color of the sky at twilight reflected in the glass facades downtown, the flash of headlights along Mulholland Drive, and the blue steel of a handgun left on a coffee table.

Blue stood its full height in the home of Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro), a career thief in a gray suit, lost in thought, pacing back and forth along twilight’s edge. It enveloped detective Will Graham (William Petersen) in a similar house on the Florida coast flooded in electric blue light – making love to his wife, disengaged and dreaming of his double in some other city, some other night. And altogether elsewhere, in yet another modernist beach house somewhere in Miami, Sonny Crockett stared into rolling tides, consumed by something inchoate and half-formed, old, inherited, blue.

In truth, there were other blues, older ones: the blue of the Aegean, the monastery, the mystics; gnostic blue, Scheherazade’s interminable midnight blue, the penitent blue of El Greco, of everything Watteau painted – and did not paint, but witnessed – and the Southern blues: the bluest of all blues, but that is another story.

2. And still, no one knows the beginning of anything.

3. Michael Mann once remarked that Dr. Strange love was, in its entirety, a third act: a climax without recourse to flashbacks or expository dialogue. All of Mann’s films refuse clear and unequivocal beginnings. His figures awaken to themselves already there (as we all do), already in the struggle to live, to reconcile their personal ethics with the cruel exigencies of the group.

For the ancients, a story began the moment a poet stepped onto a rock and drew breath to sing. Narratives pace opened like a mouth, like a wave. The poet was a face frozen in relief on a stone fountain. Beowulf begins with the Old English word “hwæt,” an exhortation to listen, a signal that someone is going to sing; the Homeric epics begin with an invocation of the Muses: “Sing, O muse...,” an invitation to the gods of music to fill the poet’s lungs with air, to help her re-member her song. The ancients began in medias res because all stories were always cut from a single endless one. Singing is a form of remembering, and the beginning of a poem is a threshold into mythic time. One hundred years reduce to mere hours, several life-times telescope into a single stanza – and is this not already cinema?

Mann’s first feature, The Jericho Mile (1979), starts in a yard at Folsom Prison as Larry Murphy (the protagonist) and a group of inmates run around a track. The yard, uniforms, doors, shutters, even the background in soft focus are saturated in blue. The film ends around the exact same track, with Murphy running alone. It is a closed loop – classical, elegant even. Murphy’s circular run is the center of a series of concentric circles. It is a theater in which Mann enacts an ethnography of gang culture at Folsom, with its hermetic codes, its petty rivalries and cruelties. The film is literally a circumambulation, a grand tour. The track mirrors the circularity of time in prison, the eternal return of identical days and routines. There are no flashbacks or reconstructions. Murphy is serving a life sentence. The entire plot is locked in a loop between those two runs; it begins at the end and ends at the beginning, like a myth, like the serpent devouring its tail. The beginning and end are two halves of a single sentence, as in Finnegans Wake. Mann will never again employ a classical structure like this, where the loop forecloses the possibility of reading the beginning as beginning or the end as end.

In Manhunter (1986), he throws it all away. Perhaps inspired by Dr. Strangelove, the entire film is a coda added to something that has already ended – a film we have not seen. This postlude begins after the most important event of Will Graham’s life: his physical and psychological battle with Hannibal Lecter, undoubtedly the film’s most compelling character. Graham is recovering at his family idyll on the beach in Florida when his former boss, Jack Crawford, visits to implore him to come back to work. Manhunter literally commences with an interrupted ending to the preceding movie, its hero staring out to sea, his fight with Lecter at an end, idling in the sand with his wife and child as the waves roll in.Graham has only a brief tête-a-tête with Lecter in Manhunter, which bears witness to the detective’s battle with the Tooth Fairy: a narcissistic William Blake (and apparent Domus magazine) fanatic who enjoys trite aphorisms about immanence and violently projecting himself into the home movies of his victims.Lecter’s pursuit and eventual capture involved a vicious attack that left Graham hospitalized and close to death, but the psychological impact on his wife and their son are mentioned only in passing, if at all. Manhunter is a sequel without a first film – a powerful succession of moods rather than a linear narrative. Mann begins The Last of the Mohicans (1992) not with a coda but with a short film, in which three men hunt deer through a wood. Observing their movement and silent communication, we intuit everything we will need to know about their relationship for the story that follows; that two of them are father and son, and one of them is both a part of and apart from the family, a white man who nonetheless moves and behaves as the others do. We see their skill and speed, their elemental relationship to the land and knowledge of the forest. After the kill, we see their prayer and respect for their prey; we witness a display of their shared faith, and then the screen fades to black and the film begins. The sequence is among the most beautiful works of Mann’s career, set like a jewel within the longer film. Like Manhunter, The Last of the Mohicans starts after the most compelling story – the family drama of how this group of three found one another – has already unfolded.

The poets of the Judeo-Christian tradition, Mann included, often betray certain anxieties about beginnings. The Old Testament begins before all stories – in the cosmic egg, the primordial soup – when the great artificer shaped undifferentiated nothingness into the material world. An entire chapter is dedicated to the start of everything, following lines of filiation and chains of cause and effect from the first man and woman to the very era of its inception. In this cosmology, the history of humanity is a history of families. This filial narrative structure appears again and again in European storytelling – in the novels of the 18th and19th centuries, in the Bildungsromane that are so often textured retellings of Genesis, set under the same skies. To know someone or something is to know its beginning; this is something fundamental to most Western ontologies. The study of being always revolves around the question of beginning, a fixation with finding those first principles from which every-thing else follows.

Islam offers an altogether more elegant solution, one in line with much of Mann’s work. Allah said “Be,” and everything became at once: man, the world, joy, sorrow, and of course, death. In the beginning was the literal word, an utterance, the copula, the connective tissue of language, thought, action – of existence itself. In this cosmology, as in ancient myths and epic poetry, everything began in medias res; we awakened to our-selves in the world, and the history of the human race is, in its entirety and like Dr. Strangelove, a third act.

4. In the third act, the question is not who a character is, but what a character does. A thief is a thief is a thief isa thief – that old Falstaffian dictum, that great thief:“’Tis my vocation, Hal; ’tis no sin for a man to labour in his vocation.” Jean Genet said that the neck was divinely shaped to be squeezed, and our hands to do the squeezing. We are what we were made to do.

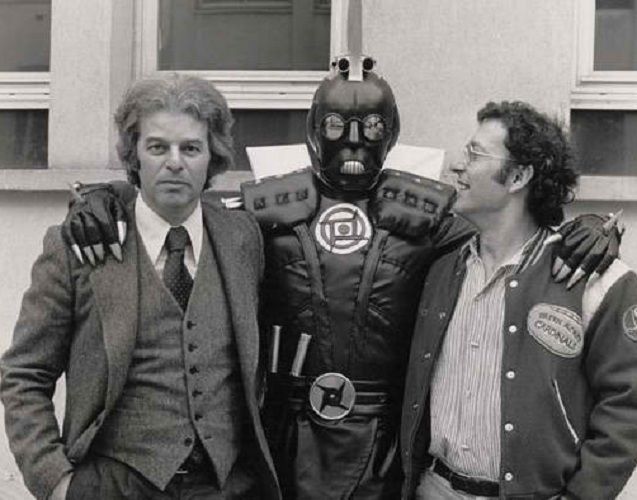

5. And Mann’s heroes do things. To interpret Frank in Thief (1981), James Caan shadowed a professional jewel thief and safecracker for nearly a year to get into character. The scenes of him breaking into safes are real; Caan is really doing it. In Manhunter, Mann employs long takes of forensic pathologists using their investigative equipment. At times, the plot almost seems like a device to showcase them. We read years of professional training in the way his bank robbers hold their guns; we see their alienation and anguish in the slope of their shoulders. Every character is an apotheosis of a very specific set of acquired professional traits. They are literally what they do and that, in many ways, is their curse.

In Ali (2001), Will Smith (in the titular role) is always moving, always shadowboxing. Slips and feints flash like pulses across his entire body, even when he is standing still. To become Muhammad Ali, one must exhibit an almost congenital fear of stillness. This activated state gives Will Smith access to Ali’s character and world; an entire cosmos is contained in how the boxer moves. The rhythms of the body hold memories the way music does In one scene, Ali trains on a rooftop as a riot rages in the streets below, and we see the city the way that he does, as a vast honeycomb pattern of inter locking rings, each one a different theater of smoke and flame and combat.

For him, everything is a boxing ring – the press conference, the courtroom, his marriage, even his own name. “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” said our sleepless poet as he surveyed colonial Dublin from a tower above it. This is a recurring shot in Mann, in which a protagonist surveys his skyline or loses himself in an infinitely receding landscape, wondering if he ever left prison at all. For Blackhat (2015), Mann controversially cast the chiseled Chris Hemsworth as a hacker and former MIT prodigy released from federal custody to help a US–Chinese government coalition avert a cyber holocaust. Mysteriously, the casting decision worked. In an re-performance of Caan’s famed diner scene from Thief, Hemsworth tells his collaborator and soon-to-be love interest Chen Lien (Tang Wei) how he survived in prison. He describes what the mystics called kenosis, an emptying of the soul so that God can fill it. The idea is very close to how the ancient poets conceived of recitation, implicit in the invocations at the beginning of their poems. To stay alive, Hemsworth had to forget who he was and submit himself to a new code of ethics. This openness to the rules of an alien world is eerily reminiscent of how actors describe accessing Mann’s world. The rules there are neither moral nor psychological, they are methodological. The only way to learn what it means to be a jewel thief is to become one.

6. Mann persistently returns to the idea of prison as a finishing school, a place in which characters acquire avocation. There is a poetic relationship between the monastery and the prison. Both operate as sites of submission; both demand a commitment to self-abnegation in the interest of survival. Many of Mann’s characters struggle to reconcile these hermetic codes with the complex and layered ethical realities of the outside world. The same tenets that define their success in criminal enterprise prevent them from forming meaningful human relationships, and the women and children in their lives bear the brunt of that failure.

Dr. Jeffrey Wig and (Russell Crowe) implodes his family life when he testifies against big tobacco. By the end of The Insider (1999), he is alone, with neither wife nor child, struggling to make sense of what he ultimately gained in the process. In Thief, as soon as Frank feels threatened he dismisses his wife and child, destroys his home and business, then declares war on the mob. InManhunter, Graham routinely puts his own wife and child in danger in his effort to protect the families of others from the Tooth Fairy. The Last of the Mohicans’ Hawkeye and Uncas are forced by circumstances to leave their respective love interests, Cora and Alice, in the hands of their nemesis Magua and his war party. Later Cora leaps to her death after witnessing the murder of Uncas, jumping off the same ledge from which he was thrown – a wife throwing herself on her husband’s funeral pyre in a form of ritual suicide.

In Heat (1995), Vincent Hanna sacrifices wife and stepdaughter in his pursuit of Neil McCauley. McCauley in turn gives up the possibility of certain escape with his lover to go back to fulfill a vendetta almost guaranteed to end in his death. Hanna and McCauley are so fixated upon each other, so locked in the endless struggle between doubles – between hunter and hunted, throat and gripping hand – that McCauley has togo back and fight Hanna to the death in the blue haze of the tarmac at LAX. When they hold hands as McCauley dies, we realize that it was their love story all along. And when Hanna stands at the window, in that white house on the beach, he is dreaming of meeting his double, who is sleepless too, in some other part of the city, and Heat is their romance.

7. A long time ago, in the dead of winter, Jorge Luis Borges also dreamt that he met his double – a much younger Borges. They sat together on the banks of the Charles River, watching fragments of ice float past. Of course, the double insisted that it was in fact his dream – not Borges’ – that they were actually in Geneva, sitting on the banks of the Rhône, and that it was several decades earlier. On a bench, unmoored from both space and time, Borges the elder spoke of what his younger counterpart would witness during the nearly 50 years between them – of love and death, of many failures and brief glimpses of happiness. They argued over the writers one despises at the beginning of one’s life and loves at the end; the various sundries that in sum make a Borges, that float by like those fragments of ice in front of them, “of one flesh, but separated like stars....”

Borges once said that he wrote short stories rather than novels because the form was capable of saying everything that one could in a story. He could always see the beginning, the end, and the thread that ran between them. The rest of it was mere detail, as old and interchangeable as ancient myths. This dream of Borges encountering Borges by a river of time says that beginning and end are both the same, that they are two halves of a single sentence. For the two always inevitably meet in a dream, neither one certain of whose dream it really is, save the dreamer who wakes to write it, and begin the story wherever it begins, and I suppose Michael Mann – among many others – is one such dreamer, as am I.

Credits

- Text: Mahfuz Sultan

Related Content

SURREALISM’S NOT DEAD: Master Filmmaker JAN ŠVANKMAJER

ROTHSTAUFFENBERG: Give him a mask and he’ll tell you the truth

“An Innocent Mind Has No Fear” by Ralf Schmerberg

DEAR JEAN-LUC GODARD

ON MESSAGE: MATT LAMBERT and ERIKA LUST

I WAS THAT ALIEN: Filmmaker ARTHUR JAFA in Conversation with HANS ULRICH OBRIST

VIRGINIE DESPENTES: Hates People, Loves Dogs.

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY’s DUNE is the Most Influential Movie Never Made