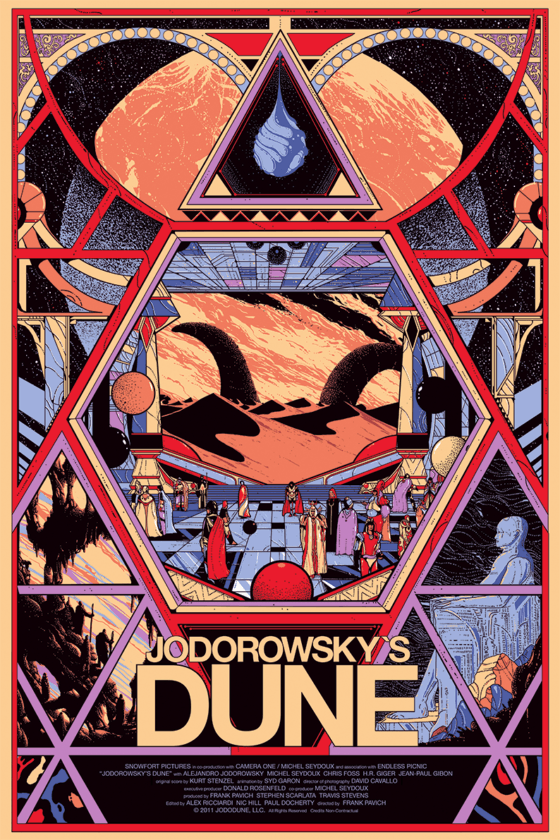

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY’s DUNE is the Most Influential Movie Never Made

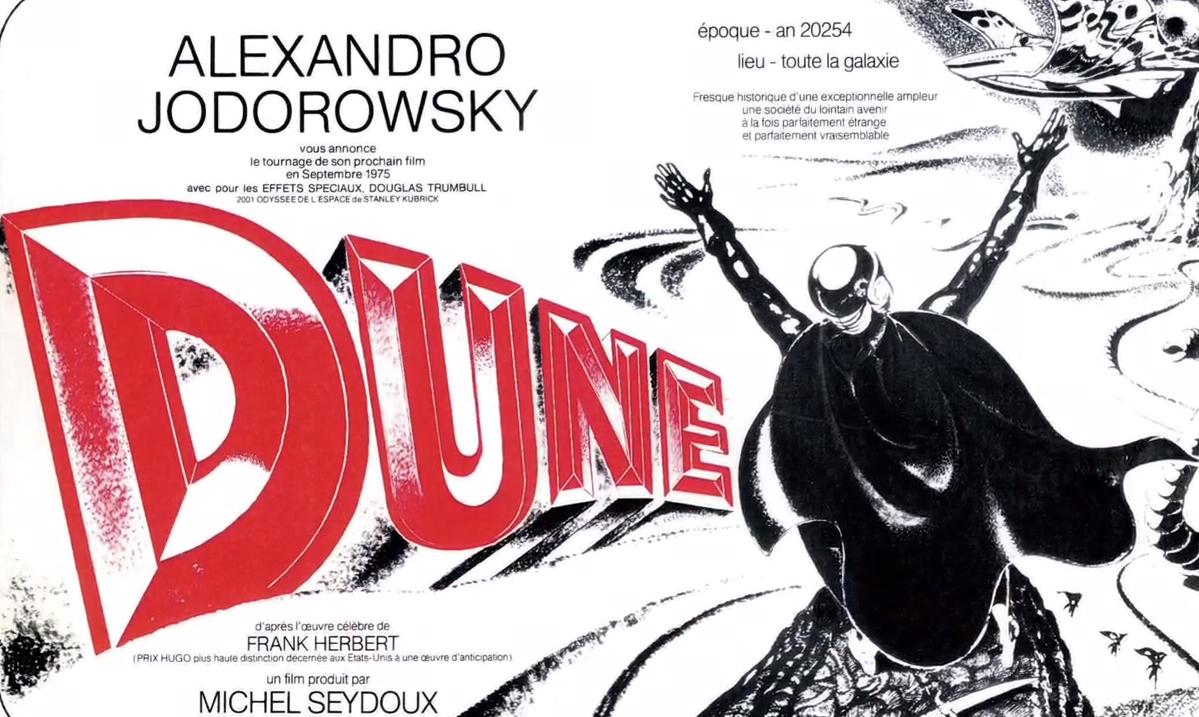

In 1974, Chilean-French director ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY set out to make what would have been one of the most ambitious movies ever realized: a 15 million dollar, 20+ hour-long adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune. Jodorowsky wanted to create “a film that gives LSD hallucinations without taking LSD,” and managed to assemble a team of spiritual warriors, including Orson Welles, Amanda Lear, Mick Jagger, and Salvador Dali, who demanded $100,000 per hour on set. The film was ultimately rejected by the studios, only to be made 10 years later by David Lynch, which resulted in one of cinema’s greatest flops. The newly-released documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune explores the ill-fated production. 032c spoke with the film’s director Frank Pavich about the project.

Hi Frank, tell us about how you got involved with Jodorowsky.

I’ve been a huge fan of Alejandro for years. When I first became aware of him, it was nearly impossible to see his films. They were completely unavailable in the U.S. for a good 30 years, owing to a big fight he had with his producer around 1973. All his films were pulled from the market, and I only saw them as third or fourth generation VHS bootlegs. You couldn’t really see what the hell was going on, but that made them all the more magical and amazing. What planet were these films from, who made them, who was this guy? We didn’t know anything.

What did he do to get all his films pulled from the market?

His producer at the time, Allen Klein, had distributed El Topo, and then went on to produce and finance The Holy Mountain. After The Holy Mountain, Klein wanted Alejandro to direct the film version of The Story of O, which is essentially the 1970s version of 50 Shades of Grey. Alejandro wanted nothing to do with that, so he called up Michel Seydoux in Paris, who had had success distributing Alejandro’s films, looking to get out of New York. Michel said “Well, what do you want to do?” And Alejandro said “Dune!” So he picked up his family and got on a plane to Paris to go make Dune, which pissed off Allen Klein, who then pulled everything. About a decade ago they finally repaired their relationship, which is why we’re able to see these films today.

In the film he said that he hadn’t even read the book.

Exactly, and I found it fascinating when I heard that he was the person who was originally going to direct the film before David Lynch’s version. As more information came together of all the characters who were to be involved, it was too interesting of a story to not pursue.

Can you give us a bit of a background on the pre-production of the film?

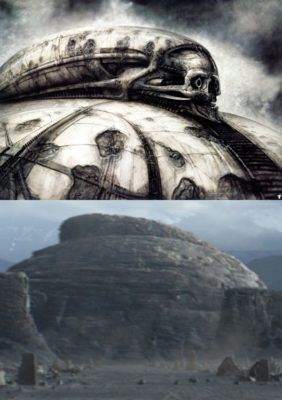

It was a two-year process. Jodorowsky demanded that the team he assembled be his “spiritual warriors.” They were mostly artists who had never worked in film before. There was Moebius, France’s most famous comic book artist, Chris Foss, a British illustrator for sci-fi paperbacks, and H.R. Giger, who now we all know of course as the designer of everything in Alien, but back then he was just this very weird, dark Swiss surrealist artist. Dan O’Bannon was the only person who had worked on a film before, but his experience was limited to Dark Star, which was essentially just John Carpenter’s thesis project at USC. Alejandro saw something special in these people.

They all worked with Alejandro, creating drawings, 3000 storyboards, all the ship designs, costumes. By the end of it all they had produced this book, as thick as a phone book, covering everything from the first scene to the last: every camera movement, every piece of dialogue, it’s all there. When they finally went to Hollywood to get the final financing, the studios didn’t believe in his vision, and the project fell apart. But all those artists involved continued that vision. Dan O’Bannon wrote Alien, and brought in H.R. Giger, Foss, and Moebius. And as we all know, Alien was such an incredibly influential film, not only visually, but thematically. Without Alien there’s no Blade Runner. These films all changed the course of film history. And these roads all lead back to Jodorowsky’s Dune. Even to this day, you can watch movies and see ideas that were first created for Dune when they were all together. I can imagine those books got passed around the studios. So even through Dune didn’t really happen as they thought it would, it’s probably the most influential movie never made.

Do you think the reason that Jodorowsky’s Dune was rejected was because he was so far removed from the Hollywood system?

It could be. He was working with a lot of untested people. But Jodorowsky wanted what he wanted, and he was quite stubborn about it. He even turned down Douglas Trumbull, who did the effects for Kubrick’s 2001 and was the most sought-after visual effects artist in the industry. Jodorowsky didn’t see him as one of the spiritual warriors.

But I think the main reason Dune didn’t happen was because Alejandro was too ahead of the time. This was pre-Star Wars. Up to this point, science fiction was 2001 and then some really shitty B movies that never really had any impact or importance. And along comes Alejandro, who wants to make this big budget space opera before such a thing even existed. The studios were unconvinced. When George Lucas was making Star Wars at Fox, they were not behind the project. They were looking for any excuse to dump it. Then of course, Star Wars proved everybody wrong and suddenly everybody wanted to make science fiction. Now all the big summer blockbusters are science fiction. Alejandro was before all of this. The studios wanted a 90 minute film and he told them “Don’t tell me what to do, if I want to make it 20 hours, it’ll be 20 hours!” On the surface, that’s crazy. But now, people sit at home and binge watch 20 hour-long episodes of television shows. They love it. People are looking for longer stories, not shorter. So the desire was there, after all.

Serials were very popular in the 1910s as well, people just forgot about them.

Exactly. And Stars Wars is kind of a serial in the end. We’re approaching numbers 7-9 in the next couple of years. People have a desire to see these characters and really be involved with them.

Do you think there was a time when the system was more adventurous?

The history books will say that in the 70s the studios were run by madmen and the director was the auteur, but there were limits to that. The director was an auteur, but only up to a certain point. Maybe for a million dollars, but not for 15. Jodo needed an extra five million dollars, which seems like nothing now, but at the time it was a huge amount. You can’t tell the Dune story for a small amount of money. Lynch’s version ended up being one of the most expensive movies of its time. Sandworms aren’t cheap.

Lynch’s Dune was also a huge failure. Why do you think they chose him over Jodorowsky?

That’s what I find so interesting. Lynch had a very similar filmography as Jodorowsky at the time. I think they were just blinded by the money. The studios started making action figures, coloring books, and even bedsheets for kids. And this movie is not a children’s movie. My mother read the review and forbid me to see it. She thought it was disgusting! But once sci-fi became a “proven” genre, they thought that anything would make money, and boy were they proven wrong.

Jodorowsky only made three more films in the following 30 years, two of which he later disowned.

It’s not that he doesn’t have the stories, but it’s still hard for him to get funding. He has a few movies that never got off the ground. He still has a grudge about The Rainbow Thief with Peter O’Toole. During a talk he gave at MoMA last week, someone asked him if there was anyone he hated and he said “I only hate my sister. I always hated her and I can’t stand her. Oh, and I also hate Peter O’Toole.” He still hates him, even if he’s dead. But maybe now it’ll be different, with his new film coming out. I’m hoping there’s a new generation of people that will discover him, because no one has a voice quite like his. He’s the most fully-formed artist I’ve ever seen.