BRANDING BHUTAN

|Victoria Camblin

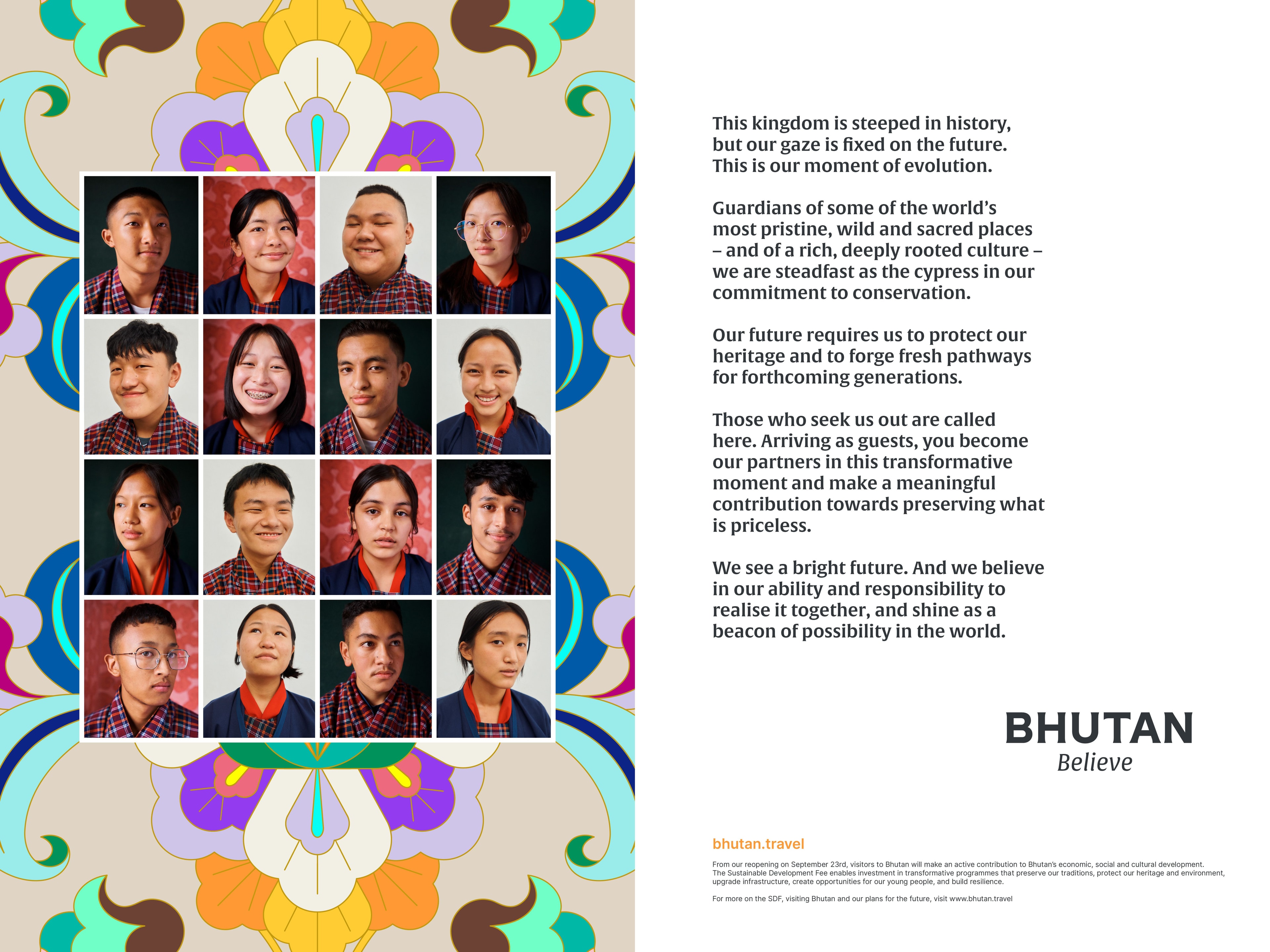

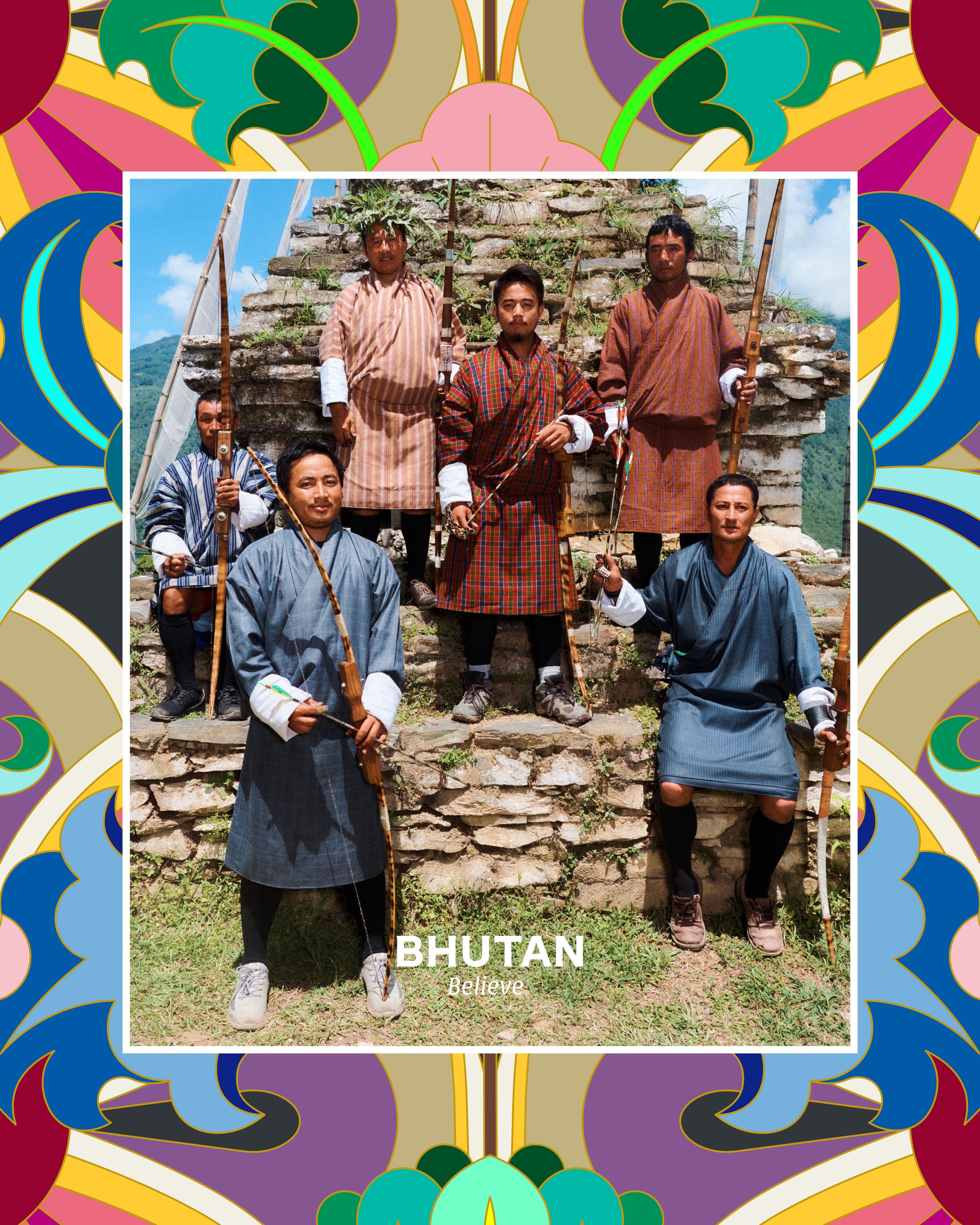

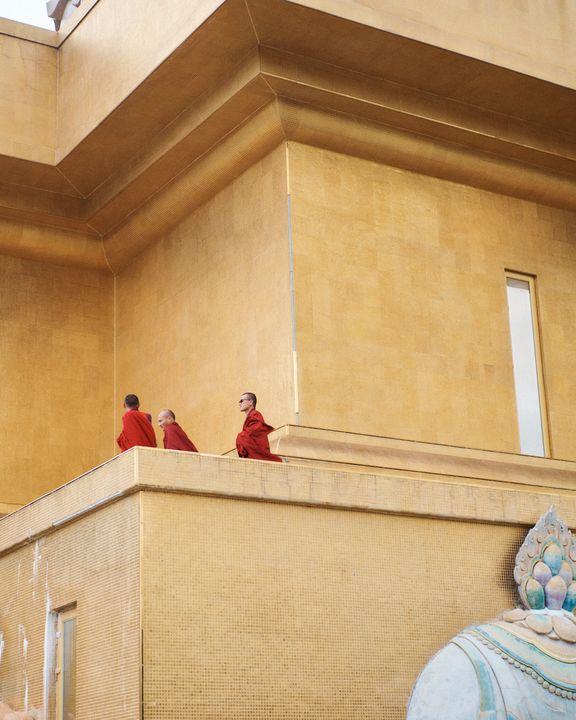

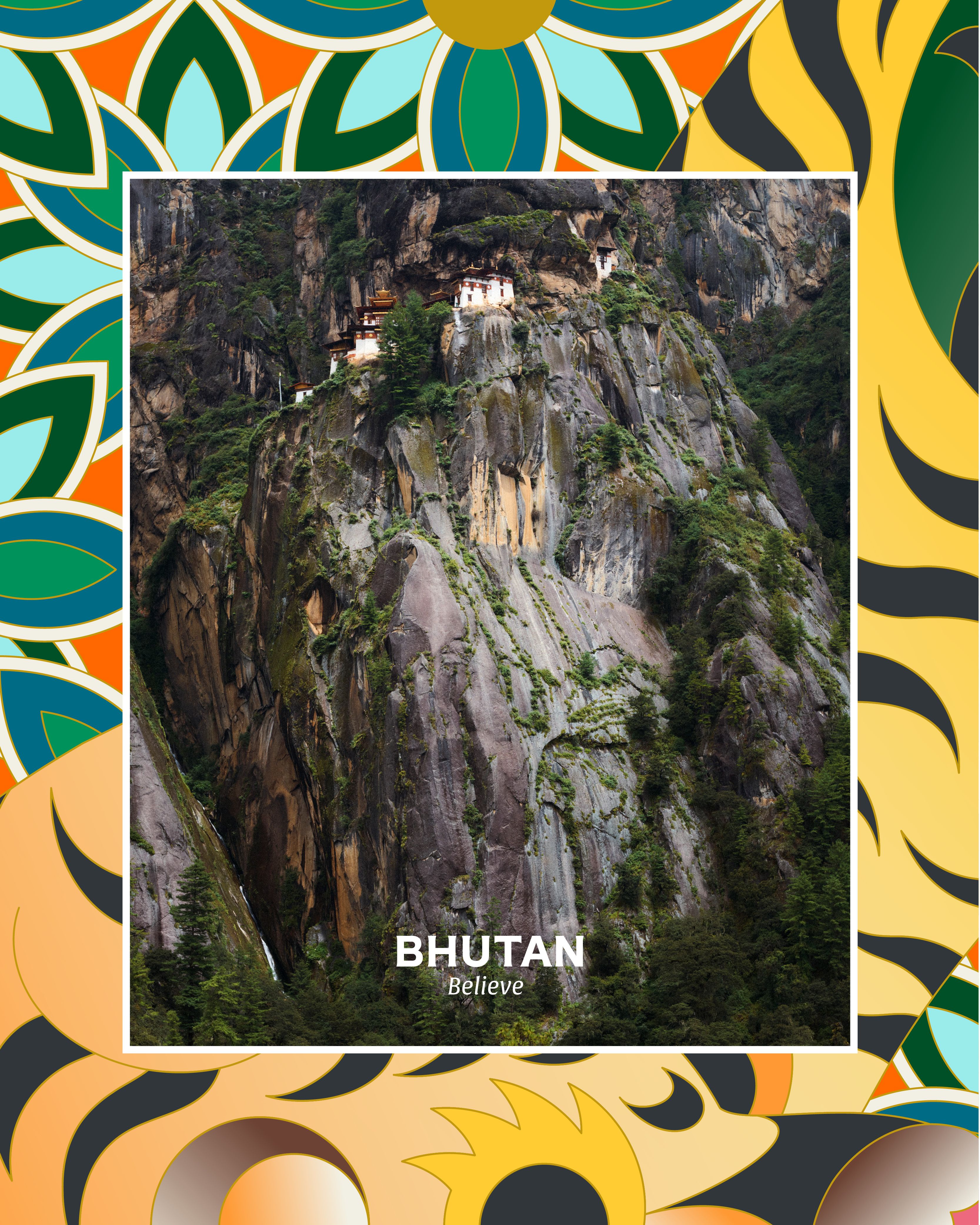

Bhutan reopened its borders in September after being closed to visitors for two years. Located in the Himalayas between India and China, the mountain kingdom seized the opportunity to launch a country-wide rebrand. Officials working on Bhutan’s expansive transformation tapped London’s MMBP & Associates to create the new identity, which pairs a simple slogan, “Believe,” with an ambitious, multi-platform campaign. This is not the typical national branding exercise of generic ads on airport billboards targeting tourists-in-transit, or jingle-led commercials broadcast on international news stations to weary guests at corporate hotels. Bhutan’s new narrative is conceived to speak to its own citizens, not just “global” ones. The rebrand was a dream project for MMBP, whose founders, Julien Beaupré Ste Marie and Hank Park, tapped their experience in luxury fashion and culture media to give Bhutan its new edge. The result is a story of cultural preservation meets technological innovation, sustainability meets transformation, and mindfulness meets adventure – and a compelling case study in the expanded field of 21st century luxury marketing.

VICTORIA CAMBLIN: So, just jumping straight into it – it's your first country as a client, is this correct?

JULIEN BEAUPRÉ STE-MARIE: We've worked in previous settings where we've worked on countries as clients, but as MMBP, yes, it is the first one.

VC: What we do as creative producers is often more political than it looks on the brief. A museum or a trade fair, for example, are means of branding a place, and cultural output is often leveraged by governments to influence how we talk about a certain locality. But rarely do we do this so directly on a national scale. Did the explicit nature of the project impact your approach?

JBSM: I think most country brands are created not directly by the country, but by what you've just mentioned: art fairs and other brands play such a big role in defining a country and in placemaking at large. What was really interesting with this project was that it was by design, deliberate. Most countries don’t necessarily work in such a deliberate manner in creating a nation brand. Bhutan was ready to do so and was in a place to do so because they are at the start of an important period of transformation in their history. They’re looking at everything from digital banking to education. They’re developing the Bhutan Baccalaureate, for example, rather than using an imported curriculum as they have done in the past. They are looking at every aspect of society and at how they can leapfrog over a whole period of development that other countries have been through – skipping that middle part, so to speak. The initiative is so thorough that the country had to look within and figure out how to communicate all that transformation inside, to its citizens, and outside its borders. That was the mandate: to create a brand fit for that era of transformation.

VC: Your portfolio is fairly “niche.” You've done major luxury labels; you’ve worked with TOILETPAPER, which is avant-garde; you’re working within the web3 space, where there are not many precedents. What made MMBP the right fit, in Bhutan’s view?

JBSM: We've worked in entertainment and with tourism boards in the past, in addition to working with luxury and retail, but our background in tech and NFTs is where the connection was, I think. There's a whole team in government working on the transformation of the country, which is very much focused on the future and innovation. I think historically, a lot of people have understood Bhutan as being about “simplicity.” That has been the whole narrative used to attract international visitors, too: “Your life is so complex and so hard. Come here to be grounded.” One of the first things we realized when we got there – we kind of had a feeling, of course – is that life is complex everywhere, so the narrative doesn’t work. Maybe it did well in selling the country, but it doesn’t reflect its reality or complexity. Bhutan is one of the first countries in the world to work on a self-sovereign, national identity on the blockchain, for example. To achieve these goals, you need people that know tech. Bhutan is working with MIT and have just opened up a Super Fab Lab, which provides free access to the latest 3D printing and other technologies. They are beginning one of the first blockchain engineering university programs in the Asia-Pacific region. The postal service there is beloved around the world for the amazing stamps they have created, and now they're selling NFTs of their stamps online. There is truth to the narrative about Bhutan a place people go to “unplug” and reconnect with themselves, but the nation really has its eyes on the future. They’re engaging with innovation and technology at the highest level.

VC: Can you give me a little bit of background about the history of the agency?

JBSM: My background is in photography and magazine publishing, and Hank and I met after I started working at an agency called Winkreative, which is the sister company of Monocle magazine.

HANK PARK: I started my career in Milan, working with fashion brands, but I joined Monocle because I was tired of only working with these cool, beautiful things. Monocle had a lot of nation brands. They redesigned Air Canada. I did not want to do some art fair’s rebrand. It's too obvious. Frieze Art Fair isn’t interesting at all. I have always wanted something totally different and bigger. I have been reading 032c since the first issue – that is the high taste level. But what if we input this level of visuals and aesthetic onto something like a government, where people don't expect it? That's what me and Julien agree on. We had a really good connection with Bhutan, so we said, “that's what we're gonna do. That’s what we have to do.” With our clients and our business, we will not be looking to create another Balenciaga campaign. We want something totally out of the box.

VC: Isn’t more of a fusional thing? As in, the luxury brand is the country, is the art fair, is the NFT platform. Like, an NFT is a luxury product. In fact, you don’t get a more luxury product than that. The way that certain countries narrate themselves as escapes is also luxury marketing – it is the language of exclusivity and rarity. The art world is the biggest culprit, really, in terms of not accepting itself as part of a luxury market and acting as though it is above the pure commerce of that. Artists will tell me they are “sick of the art world” and want to start a fashion label. People with fashion labels want to be artists. But it’s really all the same practice – it’s just the story we tell that’s off. What we’ve been calling “luxury” needs revision.

HP: That’s actually the reason we're very interested in NFTs: because normally people around us hate them! “That's not real; that’s rubbish.” We are like, “okay, let’s jump into that.” We are meeting these programming nerds, and it is really fascinating to work with them, rather than working with someone like a Juergen Teller. You see a totally different view and aesthetic, rather than having the attitude of “I am an artist, I do not believe in NFTs or in these computer technologies or whatever bullshit. I don't do that.” We can create something new and still do it with a strong aesthetic and a high-end vibe. That’s the cool challenge.

JBSM: You are right in talking about luxury earlier that in terms of the international outlook, the Bhutan project is a brand launch. They started this 200 dollar a day tourism levy. On a visit, you have to pay 200 US dollars per day, per person, as a levy to enter the country. So, the brand also serves as a tool to show why this levy is in place. If you go to Bhutan, you go there to trek, to experience the nature, the biomes. You don't go there to have a Michelin star meal and champagne. There are a few luxury resorts of course, but beyond those, luxury in its traditional sense is very limited. This tourism levy is a sustainable development fee, and the brand serves to really drive that point across. The country is becoming more developed, but they don't want to compromise on their very long held values. They could sell 30% of their forest for timber and make money, sure. But they are steadfast in protecting the culture, the land. So how do you create revenue? The tourism industry is a driver, but if you open up to mass tourism, you destroy the ecosystem that brought visitors in the first place. Instead, you could have a fee that is reinvested in the Sustainable Development Fund and goes toward health, education, and preservation. Part of our job was to explain to people that it's not expensive because it's “luxury,” but because it's a meaningful contribution to the country’s specific vision for development.

VC: Or maybe, cynically, it’s the inverse: “luxury” isn’t limited to a champagne and Michelin star experience, but one of, say, biodiversity – of ecological “wellness.” To use traditional luxury terms, it seems that part of the exercise here is marketing a kind of “exclusivity,” and that your approach was in turn very “bespoke.” We are used to the jingles on CNN world news that say “Malaysia, truly Asia,” or “India, incredible India,” – these slogans are designed to have such broad appeal that they become totally content-free. That isn’t a luxury approach. Making something incredibly thoroughly tailored as you have done for Bhutan feels like a luxury strategy – just one executed, as you say, on a far greater scale.

JBSM: It’s an interesting question. Because the levy is so new, we have no data on the people who are going to come. We were there when the country reopened, and the variety of people who came first was huge. On the tarmac, I didn't find a lot of traditional luxury travelers coming to do Forest Bathing for a few days. We met people who went because they travelled to every single country on the day of its post-Covid reopening – like, that was their only reason. We also met people planning stay for a long time, because they want to live the experience of going through a certain transformative process. On the first day of the opening Karen Darke, a British Paralympian cyclist who uses a wheelchair, flew in with a big group of people. They cycled together all the way to Bumthang, in central Bhutan. The idea of just driving there makes me tired, so I can't even imagine doing that. Some of them wrote to me after about how they really did feel transformed. And I think this is what a lot of people want to find in Bhutan at the moment: they want to leave in another state from the one they came in. But the profile is changing, for sure.

VC: High quality, low volume – that was also the essence of all the big fashion house press releases, I would say peaking just before Covid. They were talking about, say, a 7,000 dollar winter coat that you buy once and keep forever, because it is so well made and in such small quantities, so you are not creating waste. Of course, we don’t have data on whether people who buy those coats really do keep them but do know that luxury brands have an enormous carbon footprint, even if they would like us to believe that it is a “fast fashion” problem. If you didn’t have any data, what was the research process like?

JBSM: We have a very journalistic approach, actually. We started by commissioning long form articles in various subjects related to brand Bhutan – the consumer, the industry, travel reforms, the existing perception of brand Bhutan. Usually, there are two main categories: the nation brand, and the destination brand. These are different things, but they come as one in Bhutan. The destination brand is the nation brand. “Incredible India” – that is a destination brand. What's interesting about Bhutan is that the main stakeholders are internal, and they are asking for external people to buy into that same brand. So, we started with this editorial research, which gave us a lot of insight. Then we did an immersion trip, spending a lot of time on the ground, conducting interviews with people all around the country, from the private sector, from government. We met people from all different backgrounds speaking in different languages and dialects. It was a long process – a mix of workshops, meetings, immersion, formal interviews, analysis of existing data. The rest is unfolding as we speak.

VC: Did the “Believe” slogan come from you guys?

JBSM: Yes, it did. We came up with different options of course, and this is the one that resonated the most. Bhutan’s previous slogan was launched in 2008 with “Happiness is a Place” – a destination brand. They didn't really have a nation brand, so people took it on board, in the way brands just tend to creep up on you. But they didn't really like “Happiness is a Place.”

VC: You just commit to it, and eventually it sticks.

JBSM: Exactly. So, “Happiness is a Place” was the brand for a while. In our conversations, we found people were sometimes uncomfortable with it. They were like, “I actually have a lot of challenges in my life.” It’s a big thing to live up to for people visiting the country, as well. It’s very definitive, as a statement – very closed.

VC: It’s like that cliché, “you can't buy happiness.” But if you use “happiness” in a destination slogan, you are suggesting that you can buy it. It just might involve a bit of travel.

JBSM: The “Believe” tagline is also meant to inspire Bhutanese people to rally behind this period of transformation, which a challenging process for a lot of people. Things are changing at a very rapid pace. We have different pillars of messaging under “Believe” – believe in our worth, believe in ourselves, believe in nature, believe in the future, believe in elevated values – and so far, we have found that it's quite inspirational for people in Bhutan. Whereas for international travelers coming to the country, it's aspirational. It's saying, “believe that there's another path, another way of being in the world – and you are invited come and experience it.” I spoke to some people in Bhutan who said, “I love how open ended it is, because I can now project myself into the brand.” One young guy said that whenever someone asked what the slogan means he would begin his answer by saying, “well for me, it means this, and for the country, it means that.” There is an ability to take ownership of the tagline, and very quickly people started doing so.

There are other layers, of course. Bhutan is a land of beliefs, there's a mystique there, and “Believe” echoes that as well. So there a duality of inspiration and aspiration, and also an openness that people can take use in different ways, which is quite important when you're thinking about a nation brand.

VC: This reminds me of conversations I’ve had with product or and fashion designers. If you're making expensive lamps, you need to speak to the individual consumer as though you're designing something for them personally, but you are also producing on a very large scale. You need to create points of access to make it both bespoke and somehow universal. I moderated a panel discussion recently about design and sustainability, and one of the speakers suggested we consider “the planet as client,” which takes that to an even larger scale.

JBSM: That’s a great way to put it. Sustainability in Bhutan is deeply rooted, in cultural practices that are long held. In Bhutanese culture, and honestly in general, the planet, the ecosystem – these are sacred. They don't let people hike above 6000 meters. They don't want to turn themselves into a Mount Everest, even though they have very high mountains and could capitalize on it. They're not selling the forests, and you can't just go in the glacial lakes and swim. So, we didn’t just consider the environment because we had to for marketing. We considered it environment because it is so important to the culture and to the policymaking. It's an important point for people who want to travel there, of course. People want to rally behind a sustainable brand, and, as far as country brands go, Bhutan has some of the strongest credentials in the world.

VC: Usually I am critical of the way we talk about “sustainability” when what we mean is making radical changes, not preserving an industry’s status quo. But it seems Bhutan is an exception to this: the practices, heritage, and biodiversity do need to be “sustained.”

JBSM: I also don't want to paint Bhutan as some Eldorado. The world is focused on carbon at the moment, and they are a carbon sink, so that gives them very strong credentials. But it is also a landlocked country in the Himalayas, and waste management and water filtration are real issues there. We want people to see Bhutan as a complex place with challenges that they are working on. When we work with any client, and in our own business, we aim for sustainable practices. I would say 90% of the NFT projects we've done were on Flow, which is one of the most carbon efficient blockchains out there. When we do print projects, we work with people who have UV printing and recycling schemes. When we started working on the blockchain, sustainability was one of the main things. We had to convince pretty big celebrities to come on board and do NFT projects, and in terms of reputation, it's important to know what it entails in terms of carbon footprint.

When we first saw NFTs, for example these collectible PFPs, we thought, “wow, this is a crazy amount of resources and creative power building these communities – but for what? What’s the end goal here, and for which community? The community of making a little bit more money?” I mean, what brings together a banker in Hong Kong and the truck driver in Austin around these things? Pure speculation. As Hank said at the beginning, we like the tension in bringing a luxury or editorial background into nation building or into the NFT space and thinking about how we can flip it. I'm going to be honest: it doesn't always work. But when it does, like in the case of Bhutan, it's great.

VC: That’s the flip meaning of “the whole planet’s a client,” right? It's not just the planet in the environmental sense, it's that you could be doing this for an NFT platform, or a country, or a tennis racket, and bringing in the same practices. I noticed in the Bhutan campaign, that was there as some very explicit like sort of fashion vocabulary, for instance seasonal references to the cultural fabric as “autumn 2022.”

JBSM: At the beginning, sometimes you try to find the road of less friction, right? Because you need to win business, you need to survive. But I think especially Hank, since the beginning, has been really good at stopping and thinking about where we come from, what we are good at, and what we can bring people. We know amazing journalists, and the way they work really fits our way of working and gathering insight. So why would we sell ourselves as a hard data driven company when that’s not who we are? We see the value in deep research and investigative journalism, so let’s commission 4000-word articles and have journalists work for six weeks on a story. It might not work for everyone, but you have to know what your strengths are.

VC: That’s a good response to what's happening in media now – journalists are sick of how their industry is evolving and how they have less and less time and resources to do deep work. So, media professionals are going onto Substack and in house at fashion labels and start-ups – but it doesn't mean that you can't bring journalistic rigor to these fields.

JBSM: The rigor is so important on these projects. I don't want to say it's not important in publishing, but I think a lot of people work in the creative industry with the destination in mind, with the goal to make something look or sound a certain way. We’re not sending journalists with a goal of finding something specific. We give them quite free range to be investigative, and they come back with things that might not fit what we had in mind. But that's the key, right? Maybe we find we were wrong, or our expectations will be shaken. These journalists are a way to make sure that we are not safe in our assumptions.

VC: What do you do with all of this phenomenal research, though, once you have infused the final product with it? It might be nice for the public to be able to read these findings.

JBSM: Of course, we have clients who want it to stay confidential. Those articles tend to answer questions, and when you know the questions in a competitive market, you already know too much. We prepare these beautifully done briefings that circulate internally and are quite thought-provoking for internal stakeholders. We have a Medium channel called “Courant,” but most articles there are self-published to maintain client confidentiality. It would be amazing to publish a quarterly research gazette – that would be so exciting to us. But then people are going to know what you’re thinking. So, we have to balance it.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

Related Content

From the Natural Wilderness to the Digital Wilds: JACK WOLFSKIN at 40

ADAM SELMAN: How Does the Search for Rubies, Sapphires, and Emeralds in the Alps Sound?

THE COMING WORLD: Ecology as the New Politics 2030 – 2100

A Guy From Chengdu Takes Pictures in Shanghai

Modernism is Still Here (it’s Just Vacationing in the Italian Alps)

Mutant Tomatoes From The Recent Future: PIERRE - LOUIS AUVRAY’s Console Couture

Land Rovers and Concealed Footprints: A Meditation on Desert Aesthetics

OLAFUR ELIASSON: Experiencing Space