Black is a Hard Drug: ODILE DECQ

|ANDREW AYERS

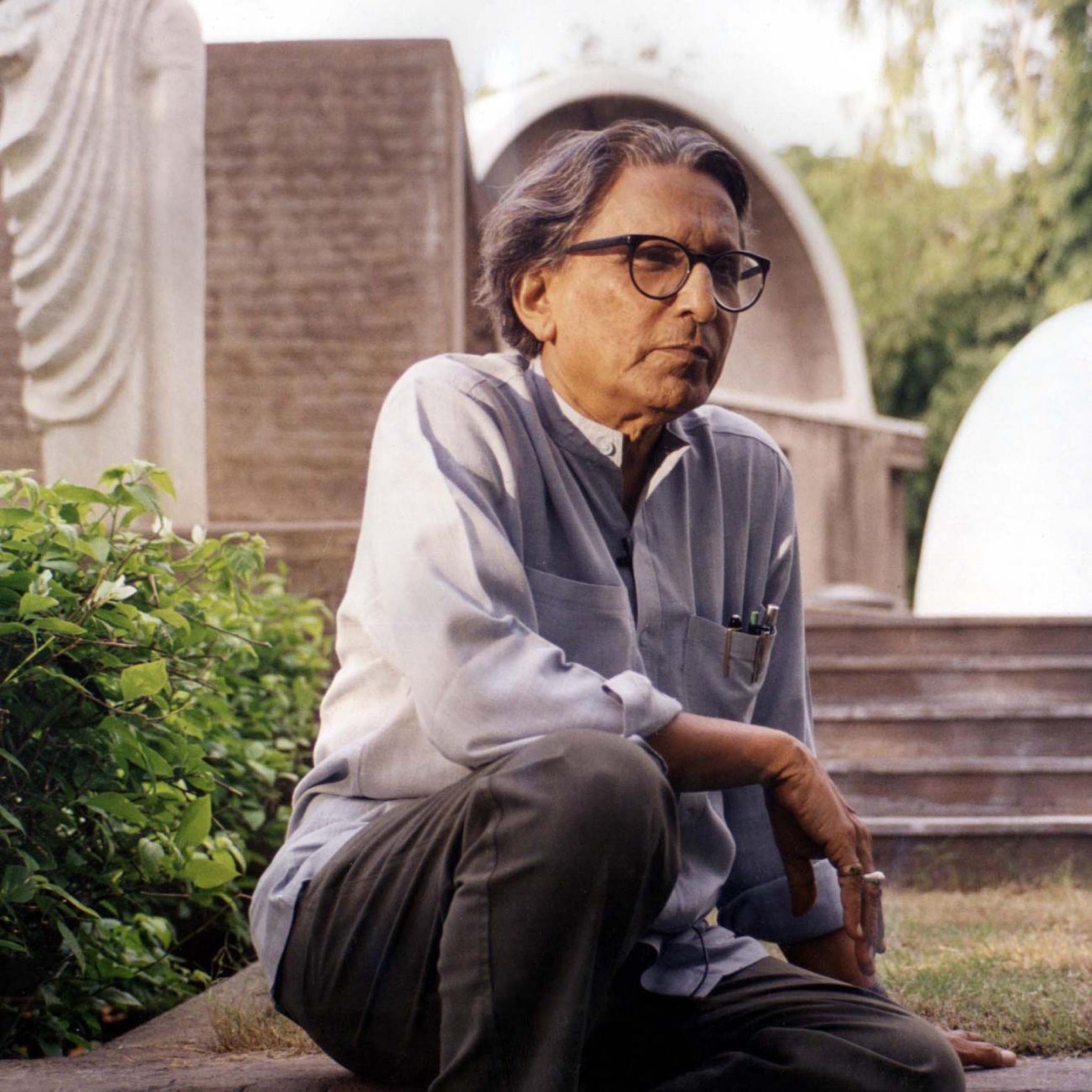

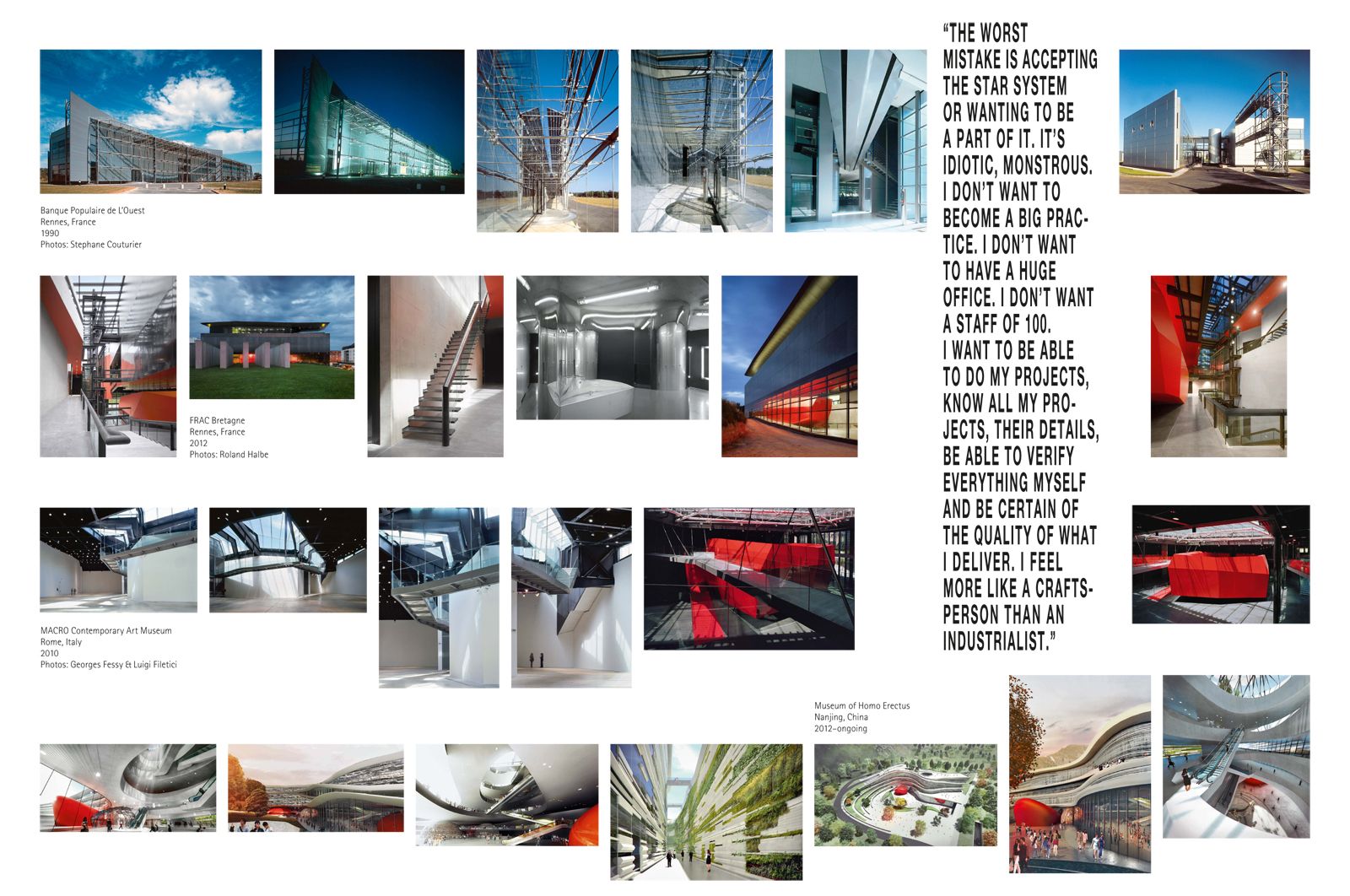

According to I.M. Pei, architects don’t really know what they’re doing until they reach 60. Which means that 58-year-old ODILE DECQ is rather precocious, since she has already entered a mature phase of her career with large, complex projects such as the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma (MACRO, 2001–10), the FRAC Bretagne in Rennes (2004–12), the just-completed Pavillon 8 in Lyon (2005–14), and the forthcoming Museum of Homo Erectus in Tangshan, China. Diverse and multifaceted, Decq’s practice includes everything from small household objects (for companies like Laguiole and Alessi) to interiors, furniture, and lighting (including pieces for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris) to full-scale urban design. Neither “iconic” nor showy photogenic, her architecture is based on the experience of the body moving through space as well as in attention to detail, both visual and behavioral. There is no obsessive signature “style” – her buildings are not riffs on one theme, and they move from the Cartesian to the fluid to the geometric as the briefs and her instincts demand. Her enemies are symmetry (“Human beings aren’t symmetrical. It’s an abstraction that doesn’t interest me!”), inauthentic use of materials, conventional thinking, and boredom. She believes in the promenade architecturale, in telling a story, in architecture as discovery, both for those who enter her buildings and for herself as a practitioner investigating her craft. Architect and avant-gardist Peter Cook, who knows Decq well, has said of her:

“In all my travels, and at all the points in a constantly unraveling web of architectural vitality, I can rarely match the Decq phenomenon … a mean composer of plans and even meaner delineator of the built carcass and very clear about it … a true pedagogue, with both an overview of what architectural education is really about plus the added advantage of being able to inspire those around her … To a former spotty English youth such as myself who had gazed wistfully at pictures of Juliette Greco, [my] first sighting [of Decq] sustained [her] myth. If anything, I was reminded of another first sighting – that of the Smithsons, more than 20 years before: visions in silver plastic, but sustained by a string of provocative ideas.”

Born and raised in the small town of Laval, Brittany, Decq studied architecture first in Rennes and then in Paris, adding urbanism to her repertoire at Sciences Po. She opened her office after graduating, and her early years in practice, in partnership with her husband, Benoît Cornette (who was tragically killed in a car accident in 1998), were a time of experimentation, little money, and finding her way both professionally and artistically. Success came suddenly, at the beginning of the 1990s, with the headquarters of the Banque Populaire de l’Ouest in Rennes followed by a Golden Lion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 1996. Since then, despite the pain of Cornette’s absence, she has gone from strength to strength, her projects constantly growing in size, scope, complexity, and daring. For Claude Parent, doyen of the French architectural scene, Decq’s design for the MACRO was a “petit chef d’oeuvre,” a “bijou of insertion” that, “without ever falling into mannerism” or sacrificing its own constructive logic, integrated itself perfectly into its environment.

As well as admiring the force of her architecture, Parent was seduced by Decq’s strength of personality, her refusal to recognize limits, her unshakeable will. Had she not become an architect, he concluded, she would have been a sailor, “striking across the waves, tearing her sails, subjugating the sea.” Seattlebased architect Peter Pran describes her work as “always a surprise. You do not know what she will create next; she does not repeat herself … What sets her work and work method apart is how she asks questions and analyzes all issues pertaining to architecture and our architectural culture: she undermines the conventional and subverts it.” It’s a sentiment with which French critic and historian Michel Vernes entirely concurs: “The work of this exceptional architect has a constant tendency to make us forget the customary canons of beauty: with her head on her shoulders and a sturdy heart, she defies the present in the name of the future.”

Strength and tenacity are qualities required in any architect, but for a woman in the male-dominated profession, they are even more necessary. At the end of 2013, after practicing for 35 years, Decq was named French Female Architect of the Year – a rather delicious irony given that the profession’s legendary machisme very nearly stopped her taking up the Tsquare at all. “To begin with,” she says, “I didn’t consider architecture because I thought it wasn’t possible for a girl.”

“My father was absolutely certain that architecture wasn’t for girls, and at the time there were very few woman architects, so the question never even came up. I wanted to do something in the arts – a drawing teacher had introduced me to architecture, the decorative arts, urbanism,andsoon–andIalsohada girlfriend who’d gone to study art history in Rennes, so I decided to follow her. In Rennes I got to know some of the architecture students and went to visit the architecture school to see what they were doing. One day I asked, ‘But are there girls who are doing architecture too? Is it possible?’ ‘Yes, yes,’ they replied, ‘you can sit the entrance exam if you like.’ So I sat the exam and passed it. Afterwards I went home to tell my parents. My father’s reaction was: ‘But it’s not possible for girls, there aren’t any girls in architecture!’ And to make me understand he invited an architect home for lunch, a Parisian who came to Laval from time to time. So this gentleman came, because of course it was a man, and at the end of the meal he turned to me and said, ‘So my petite demoiselle’ – that was really how he spoke – ‘I hear you want to be an architect. What do you want to build?’ And I replied, without really thinking, ‘A theater!’ He looked rather surprised and then turned to my parents and said, ‘Listen, I’ll tell you one thing. We don’t know if she’ll do a theater or not, but it’s great that young girls today are interested in architecture, because with their common sense they’ll be very good at designing kitchen cupboards and work surfaces.’ Back in Rennes I said to myself that since I was so endowed with common sense, I would use it for everything but kitchens and cupboards!”

Indeed, in Decq’s apartment, which she has entirely remodeled, the kitchen still isn’t finished and probably never will be. (To get water for cooking she has to use the bathroom faucet; she tells guests she’s “going to the well.”) She also hasn’t yet had the opportunity to build a theater, but “it doesn’t really matter. I don’t have any goals as to what I absolutely want to build. Each time an opportunity arises for something I’ve never done before, I’m interested in it on principle. What excites me is discovery, setting out on an adventure and seeing where it will take me.” This explains the great diversity of her oeuvre: housing (both apartment buildings and individual residences), museums and galleries, restaurants, transportation facilities, university buildings, offices, temporary pavilions, and even a yacht. Contrary to standard practice in France, where concrete has reigned supreme for the last century, Decq is far more interested in glass and steel, something she discovered in London, though it was initially more the music scene that attracted her.

“Today’s students are very different… They want it to be more like high school. They want to be taken care of. Whereas that was absolutely the opposite of what I wanted – I wanted my independence!”

““In the 1980s we [Decq and Cornette] spent every weekend in London, because we were passionate about the music scene. We knew loads of groups and had tons of friends there. So we spent our weekends at concerts and on the Kings Road, like everyone else, but on Sundays we went to the Isle of Dogs, which was being redeveloped at the time – Canary Wharf and all that. That’s how we discovered metal construction. And that’s why, for our first big project in 1988, the Banque Populaire de l’Ouest in Rennes, we proposed a metal-framed building, something that had never been done in France for an office building. Never! It was only afterwards that we found this out. For us, having seen tons of metal-framed buildings, it seemed totally normal. We knew every little detail of metal construction and knew how to design them.”

Although later Decq admitted that this wasn’t quite the case.

“Once we’d won the competition for the Banque Populaire, we said to ourselves, ‘How are we going to build it?’ We didn’t know an engineer capable of doing it with us. Peter Terrell, an Englishman who’d just opened his engineering firm in Paris, suggested we talk to Peter Rice.’”

That’s the legendary Peter Rice of RFR (Rice Francis Ritchie), who invented the suspended, cable-tensed glazing that has become so ubiquitous today. Despite her reservations that Rice wouldn’t be interested in working with such a young, small firm, Decq, never lacking in mettle, went to see him.

“I showed him my project and he said, ‘What interests me is the façade. How are you going to get light through it?’ And we talked about light, and about space, and not at all about structure, which was interesting. And he agreed to work with us.”

Inaugurated in 1990, the Banque Populaire brought Decq instant recognition and effectively launched the firm’s career. If it now seems very much of its era – or something of an œuvre de jeunesse – it demonstrates all its architect’s pluck

with a dramatic plan that allows for a fetishistic orgy of cable-tensed steel and glass running along 120 meters of main façade. Since then, Decq’s preference for metallic construction has never waned.

“I don’t like concrete. When you go on site, it’s dusty and dirty! [Laughs.] No, it’s not just that. Concrete is less precise – I prefer steel. I prefer the articulation, the construction, the structure. I prefer to imagine the construction and the manner of construction at the same time as I imagine the space, which is something you don’t do with concrete. With metal-framed buildings you have to think about the construction itself, and not just draw plans that you give to the engineer who makes sure the concrete comes down in the right place. When you’re working with a metal frame, the advantage is that you design it yourself, and you think in terms of both structure and space simultaneously – the two are indivisible.”

Ever since the first flowering of iron and steel structures in the 19th century, glass has been their handmaiden, from early railway stations with their glazed roofs to the thousands of panes that twinkled on London’s Crystal Palace (1851). And for Decq, it’s the stuff of the future.

“Glass is by far the most high-performance material today, the one that’s being constantly reinvented with new technology, the one you can work with the most. I like the materiality of glass. I like the freedom you have with it and the freedom of space you can give with glass.”

Having commissioned all-glass houses from her, many of Decq’s clients agree.

“Right now I’m doing three houses in Brittany for three Englishmen who’ve asked me to do them entirely in glass – there isn’t a single partition that isn’t in glass! And for the first of the houses, the client is saying that perhaps the intermediary floor and also the staircase should be in glass.

The gentleman in question has a disease that is causing his eyesight to diminish progressively, so he needs light to flood into his home. He’s an industrialist who works with glass and metal in London, and he’s building the house himself. It comprises pivoted cuboid volumes entirely clad in glass – black translucent glass so that it diffuses the light but also protects you from it.”

Other projects in which glass has a prominent role are the Brittany Region’s contemporary art gallery (FRAC Bretagne) and Pavillon 8, a mixed-use complex housing an art foundation as well as the headquarters of an events company. Both buildings feature monumental glass-clad boxes, and in both, as in the houses in Brittany, the glass is tinted black.

Black, it turns out, is fundamental to who Decq is. The cliché of the architect clad from head to toe in the color arose in the late 80s, but Decq’s penchant for somber attire predates all that: it originated in her love affair with London and the English music scene. Decq has no qualms about doing the time warp again, for she is never not decked out in full goth garb: backcombed, anthracite tresses; Siouxsie eye shadow; black nails; black lipstick. She even drives a black Mini from the 1980s.

“Black is London. It’s rock, it’s music – everything that happened just after I graduated. I was platinum blonde when I was a student in the 1970s – blonde, blonde, blonde! Then I went over to all black when I started to understand that in England things were blacker.”

The color of mourning?

“That’s what my father used to say! And I would reply, ‘But no, it isn’t about mourning. Priests aren’t in mourning!’ [Laughs.] I tried to find references he could understand. And once I’d gone over to black, I could never change, because once you’ve fallen into it, you’re done for. You can’t get out. Black is a hard drug. If I go into a clothes store and there isn’t any black, I don’t even look. I just walk out! Black is a fantastic color: it absorbs. It’s a color that’s neutral but strong, that stands out while still being extremely elegant. All the rebels were dressed in black, all those who resisted, the anarchists, the rockers.”

Slowly but surely, black has crept into Decq’s buildings as well.

“It’s only recently that I’ve used black in my buildings. Even back at the time of the Banque Populaire, clients would say – because I was always dressed in black – ‘You’re going to put black in the building!’ But I never did because I didn’t want to impose black on people. It started with the MAC RO, where it was complicated to build in metal because of the stringent fire regulations in Italy – while I managed to get steel accepted for the roof, I was forced to use concrete for some of the rest. In the renderings, I’d made the concrete the color of concrete, but then I started trying out samples: white, light gray, concrete gray, then a little darker, and in the end I said, ‘Right, let’s try black.’ When I saw it, I asked for a bigger sample, and then a journalist who was there to interview me said, ‘Go on, go for it! Do it in black!’ And so I said, ‘Okay, let’s do all the walls in black.’ And once all the walls were black, I said, ‘Let’s do everything in black!’ And I had everything painted black, even the smoke detectors. And it looked fantastic.”

Now, red sets off the black in Decq’s buildings: a beating heart of an auditorium in both the FRAC Centre and the MACRO, vermilion underbelly and furnishings in the offices of Pavillon 8. Is there something of Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir in all of this? Not at all, Decq replies. It had never even occurred to her; the combination was simply instinctive. And were she to analyze that instinct? “It’s an instinct, not a problem. Why do you want me to analyze it?” she laughs. But now, she says, her instinct is guiding her towards something chromatically more radical:

“For a little while I’ve been asking myself if I shouldn’t only do black buildings from now on. It’s started, but it could be even more radical. At the same time I can sense that I’m going to imprison myself in something that bores me, and I don’t like it when things become obligatory.”

I’m still at war. Against received ideas. Against the principle of precaution. Against today’s general timidity.

Surely she makes the rules so she can break them?

“Yes, but as I said earlier, once you’re bitten by black you can’t go back. It’s a hard drug. I’m trying to resist, but …”

Resistance, rebellion, revolt: these are also fundamental traits of Decq’s character. As a teenager, she admits, she became “extremely difficult” and was thrown out of every school in Laval. When the events of May 1968 rocked France, Decq’s parents had to literally lock up their 12-year-old daughter in her room to stop her from joining the protests. But this was when anarchy and rebellion were in fashion, as became clear when Decq arrived in Paris to study at UP6 (now the École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Paris La Villette), one of the architecture schools founded in France after the break-up of the beauxarts system in the wake of 1968.

“It was the school that had the most students, and it was total chaos. Indeed our studies were practically zero because we were permanently on strike – on the teaching staff were [Roland] Castro [a former Maoist revolutionary], [Jean-Pierre] Le Dantec [another Maoist revolutionary], and all those people who’d been in involved in May 68. It really was a total mess. We barely went to class. In my fourth or fifth year I hardly knew how to do anything – I was asked to do an axonometric, but I’d never learned how! I had to earn my living at the time, and because we were almost never in school I was able to work [for the architectural theorist Philippe Boudon]. In the building where Boudon had his offices there was also [Alain] Sarfati’s architecture firm, and I went to see a girlfriend who worked for Sarfati and got her to teach me how to do axonometrics. You had to have a lot of character to get through UP6 and make an education for yourself. But when in Paris, in 1991 or 1992, there was the exhibition of 40 architects under 40, 60 percent of them came from UP6, including Dominique Perrault and me. Because it was the most messed-up school, you could really learn things for yourself.”

Teaching has formed an integral part of Decq’s practice for the past 25 years, and she served five years as head of Paris’s École Spéciale d’Architecture until 2012. Still, reconciling her own educational experience with today’s climate has sometimes proven problematic.

“In France architectural education today has become much more like high school. As director I felt very embarrassed sometimes when we had to make students redo a whole year – I found it absurd not to be able to let them find their own ways and create their own path as I had done. But I couldn’t because we were operating under a very strict pedagogical code, the Bologna rules, and the education ministry’s stipulations. But today’s students are very different, too. They want it to be more like high school. They want to be taken care of. Whereas that was absolutely the opposite of what I wanted – I wanted my independence!”

Perhaps she will be able to find the middle ground with her latest project, a new architecture school in Lyon opening this September with a name that says it all: “Confluence: Institute for Innovation and Creative Strategies in Architecture.” Rather than offering a traditional architectural cursus, the school aims to find novel ways of approaching the discipline through partnerships with artists, scientists, neurologists, and industry.

The perception, manipulation, and understanding of space are particular areas of interest for Decq. Reaction in France has been mixed, with many in the profession carping at what they see as an upstart institution that, as a privately funded initiative, escapes the usual French state control and is therefore instantly suspect to eyes adjusted to bureaucracy. But for Decq, escaping control and bureaucracy to reach new horizons – recapturing the “anything’s possible” optimism of her youth – is precisely the point … and a daily combat.

“I’m still at war. Against received ideas. Against the principle of precaution. Against today’s general timidity. Against the fact that no one is prepared to take risks anymore, or, consequently, responsibility. Against the fact that people think the world is getting worse while I think it can always get better. There are so many things to fight against. Every morning I set out for the battlefield.”

Credits

- Text: ANDREW AYERS

- Photography: JUERGEN TELLER