ART AT WAR: BORIS MIKHAILOV and WOLFGANG TILLMANS in Ukraine

|Shane Anderson

Wolfgang Tillmans, curator Maria Isserlis, and Vita and Boris Mikhailov in Tillmans’ studio. Photo: Tim Davies.

There are many ways to write about an exhibition you haven’t seen. You can pretend that you attended the opening as you regurgitate the press release, or you can pilfer as much as you possibly can from those who fulfilled their journalistic duty, unlike you. Although such strategies may help to obfuscate your shame, it would be more enlightening to explain why you haven’t been.

In this case, the question isn’t one of effort. A journey was made to Berlin in late February to hear the artists and one of the curators speak during an event at the Hamburger Bahnhof. Countless hours have been dedicated to poring over their photographs and the stories that have been told about them. Nor is the question about the lack of attendance one of the exhibition’s not having opened yet – or not only. Even if its opening had occurred last week, I still wouldn’t have visited “Pairs Skating: Wolfgang Tillmans and Boris Mikhailov” in Kharkiv. That’s because, at the time of this writing, 1,111 days have passed since Russia invaded Ukraine, and traveling to a city that is only some 35 kilometers from the front line to attend an art show is not advisable for either the artists or anyone reporting on it.

Over the past three years, Kharkiv, in eastern Ukraine, has been struck by more than 20,000 Russian drones and has been shelled by numerous cluster bombings in discriminately targeted at densely populated areas, including supermarkets, apartment blocks, and a playground. Unlike such smaller cities as Popasna or Bakhmut, Kharkiv has not been completely wiped off the map, yet it has lost about 500,000 of its two million inhabitants since February 24, 2022, either through displacement or death.

Those who have stayed, however, have fought, continuously pushing the Russian invaders away from the city while withstanding many violations of international law, including some acts that the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine has deemed war crimes. The residents of the city have fought, too, to retain some semblance of life, which has been reduced to rubble and air raid sirens. Three and a half days a week, children attend school in a bunker ten meters underground, and concerts are given in a 400-seat hall in the basement of the National Opera’s Brutalist building. France 24 reports that, at a recent performance, the audience called local singer Yulia Antonova their oxygen.

Creativity is vital in a world under attack. Whether it’s French arias or contemporary photography or a puppet show makes no difference. Art, in the words of Gerhard Richter, “is the highest form of hope.”

The exhibition “Pairs Skating: Wolfgang Tillmans and Boris Mikhailov" is on view at the YermilovCentre in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Tatiana Kochubinska, co-curator of “Pairs Skating,” echoed Richter’s sentiment over a Zoom call. “Art is becoming more crucial. After three years, there’s now tension with the US, and international diplomacy is failing. We are facing this failure and are trying to overcome our isolation. Art remains a way for us to appreciate our human values. It’s important to bring art to the exact location where the fight for values is occurring.”

Kochubinska’s co-curator, Maria Isserlis, added: “There is very little opportunity for cultural events, because of the constant shelling. People are in danger if they leave the house. But you need culture in your daily life. If you take it all away, it’s hard to maintain some form of sanity.”

There’s a paradox here that verges on the absurd. Shipping exhibition-quality prints of work by two world-renowned photographers from Berlin to a city that was literally struck by a Shahed drone ten minutes before I wrote this sentence seems like an insane thing to do. The logistics alone must be bonkers. But that’s what is happening in preparation for the show that will open on April 25 and will run until September 28, 2025, in the YermilovCentre. The idea for this exhibition came, in part, from the Ribbon International initiative, which is working with institutions in Ukraine and others internationally to commission and support exhibitions and activations. It wasn’t Ribbon International’s initiative alone, though; the curators and artists eagerly wanted this exhibition, too.

What might be even more insane is that the exhibition “Pairs Skating” was in no way designed for a larger audience, even though it could conceivably tour Ukrainian railways and beyond. Tillmans currently has a massive retrospective of his work at the Albertinum in Dresden, and Mikhailov is showing at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York; it would be of great interest for many to be invited into the conversation between them. Instead, the show has one iteration, and Isserlis suggested that “Pairs Skating” was conceived for the people of Kharkiv as a way of paying respect to them: “We wanted to create something unique for Kharkiv.” Kochubinska added that Kharkiv has a rich avantgarde tradition and, for her, “it’s a political statement [to say] that this tradition is not broken, despite the war.”

But could the war stop the exhibition? Maybe. And yet, when the artists were asked what they would do if the show became impossible in Kharkiv, they both agreed that there is no plan B. It’s Kharkiv or bust.

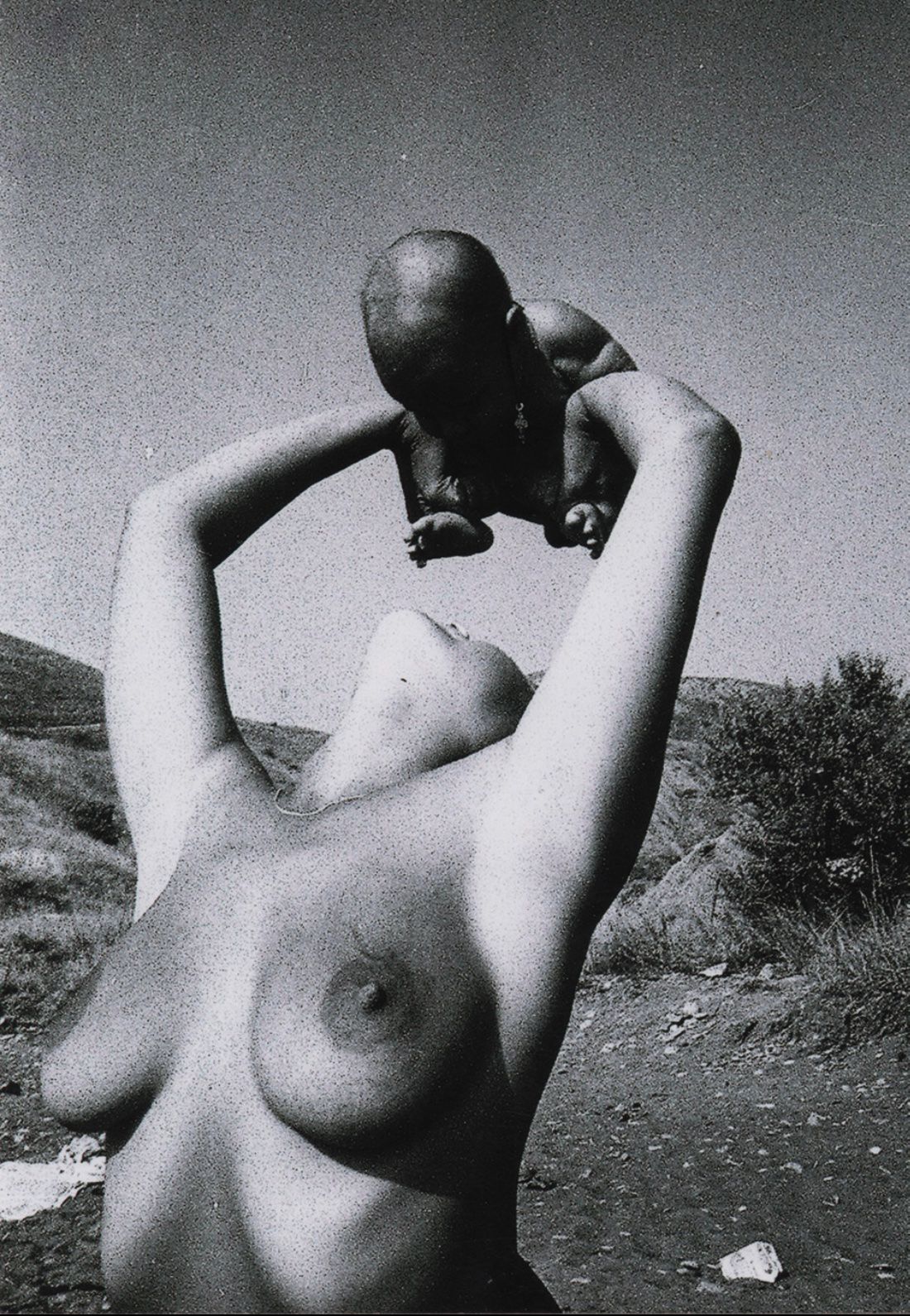

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled from “Crimea, Fox Bay” series, 1995. © Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov and Galerie Barbara Weiss

Another way to write about an exhibition you haven’t seen is to imagine what it could be – to dream about the pictures that might be selected. With these two photographers, doing so entails navigating thick groves of books, mountains of material. Boris Mikhailov, winner of the 2000 Hasselblad Award in Photography, has published more than 20 books of his photographs and has been active as an artist for six decades, with many exhibitions in illustrious museums. Similarly, Wolfgang Tillmans, winner of the 2000 Turner Prize and 2015 Hasselblad Award, has published more than 30 books of his photographs and has been active as an artist for four decades, with many exhibitions in illustrious museums. Faced with all these years, all this material, you could select favorites and set them aside like a child with baseball cards, constructing your own perfect exhibition. But this exercise inevitably leads to the question: why these two photographers? And why the two of them together, in Kharkiv?

Although he has lived on and off in Berlin since 2007, Boris Mikhailov is deeply tied to Kharkiv. Born there in 1938, in what once was the capital of Soviet Ukraine, Mikhailov even stated in Aperture that “Kharkiv and I are one and the same.” A member of the first generation of the Kharkiv School of Photography – which challenged the rigid constraints of state-sanctioned Soviet Socialist Realism with subversive photos of everyday life, full of dark humor and experimental techniques – Mikhailov is a self-taught photographer.

Trained as an engineer, he began making work in 1962 to document the state-owned factory where he was employed. He was fired from his engineering job after a KGB agent discovered that he was using the factory’s darkroom to develop nude photos of his wife. Although this incident proved to be the end of his employable career, it was the start of his artistic life, and he subsisted on selling his photos through the black market for some time. During that period, he made books of his photographs that were passed along samizdat-style. He also showed his work in “dissident kitchens,” clandestine exhibitions organized in the private flats of nonconformist friends, the core of whom later became the Kharkiv School of Photography.

Unrolling "The State We’re In, A" inside the YermilovCentre. Photo: Oleksandr Osipov.

Beginnings are never irrelevant. They are the seeds that sprout into crocuses that promise the fruits of late summer’s blackberry plants. The seeds here are the documentation of everyday life, which germinated in the factory, and nudity, which hasn’t been limited to his wife. In Mikhailov’s early work, such as “Yesterday’s Sandwich” (1960s–70s), where the artist superimposed two images to create bizarre and dreamlike compositions, you can find a naked woman overlaid with a line of people bundled up in winter jackets and hats; another woman – this one lying on the ground, her hands behind her head – with layers of foliage covering her legs and running up, along her breastbone, to cover her face; and yet another woman, standing, pensive, with a rug superimposed over her, from her breasts and to her knees, so that it seems to be a dress.

Although continually shooting the nudeness of others, Mikhailov has not ignored his own body. In the hilarious series “I Am Not I” (1992), the artist poses, in exaggerated gestures, with props ranging from a sword to a dildo to an enema bag, while he wears a curly David Hasselhoff-esque wig of curls.

Nudity and documentation at times converge, as in Mikhailov’s series “Case History” (1997–98), which looks at the harsh reality of those who have been left homeless in Kharkiv due to the collapse of the Soviet Union. “Case History” features many raw yet deeply empathetic portraits of toothless and dirty faces, of bare-chested displaced people, who, as Mikhailov told MoMA’s Inside/Out, “posed nude without shame.” The notion of posing is important here, as the photos are all staged, and he paid his subjects a month’s pension to take their photos.

Although this approach might transgress certain traditional ethics that concern authenticity, control, and documentary integrity in photography, those things never seemed to be the point of “Case History.” Instead, the series involved showing something that was never meant to be shown – namely, the subjects’ desperation and dependence, which existed long before Mikhailov gave them some hryvnia and helped them more than the government did. Despite his imagery being staged, no sentimentalization or beautification of poverty occurs here. In their place is human dignity beaming amid defiant gazes, shy smiles, eyes full of love, in a world that is nakedly absurd.

Take, for instance, a young man who seems to have fallen down but is being held up by two others. He looks pissed, in many senses of the word, and resembles Christ being taken down from the cross at Golgotha. Calling to mind Caravaggio’s Deposition (c.1600–04), Mikhailov’s subject seems to be asking, “Why hast Thou forsaken me?” The young man is shirtless in the snow, like so many others in “Case History,” and you could say that Mikhailov is showing the bare truth of their bare survival.

Hanging "The State We’re In, A" inside the YermilovCentre. Photo: Oleksandr Osipov.

All of this nakedness is just one strategy among many that Mikhailov has employed. His interests are, at times, experimental, as in the book Structures of Madness, or Why Shepherds Living in the Mountains Often Go Crazy (2013), which contrasts images of rock formations with drawings of deformed faces, genitalia, and bodies that Mikhailov makes us see in the stone. At other times, his interests are staged, as in the series “Men’s Talk” (2011), where the photographer took pictures of a sometimes tender, sometimes enraged gay couple within the set of a prison cell in Ukraine.

Always, though, he maintains interest in “what’s ‘average,’ ‘everyday,’” as he writes in Viscidity (1982). It could take the form – in Look at Me, I Look at Water, or Per version of Repose (1999), for example – of photographing a man caught eating cherries by a bus stop and throwing the pits into a trash bin “with bloody hands and the gestures of a prophet,” as the text underneath the image explains. Or it might be biographical, as in Viscidity, which features a picture of a field and an accompanying text: “Here, a plane cast its shadow on me.”

Often, Mikhailov’s photos seem to capture what can never be captured. In the words of Bernd Stiegler, “Mikhailov photographs the passing, the fleeting and momentary things that are still alive in frozen history, pulsing underneath the crumbling plaster, the rust of the pipes, and the peeling facades.”

Wolfgang Tillmans, "The State We’re In, A," 2015.

The truth is rarely pretty – which is why Mikhailov’s photographs can sometimes be ugly. He tends to let go of traditional aesthetics and out- ward beauty, and his resulting images, as he told the Louisiana Channel, are “not good, they’re mediocre or bad … reality must not be artistic.” What’s important to him, as he told Aperture, is “the innermost depths of life and humanity.” And yet, in this aim, he unearths great beauty – often, with a wicked sense of humor.

A similar tension between poeticization and documentation can be found in the work of Wolfgang Tillmans, which also flirts with human vulnerability and its strength.

As a child Tillmans wanted to be a gardener or an astronomer. Born in Remscheid, West Germany, in 1968, he took his first photos at age ten – mostly of astronomical phenomena and plane-kissed skies, early fascinations that would occupy him later in the photography books Concorde (1997) and Truth Study Center (2005). Despite this early fascination, he bought his first camera at age 20, in Hamburg, while fulfilling his obligatory civil service duty as a conscientious objector to compulsory military enlistment.

By day, Tillmans cared for the elderly and answered phones, and by night, he would go clubbing and take pictures, some of which were published in the magazine i-D in 1989. Although he became a staple in the burgeoning techno scene of that German port city, where he also exhibited abstract Xerox art in a gallery, Tillmans’ restlessness took him to Bournemouth, England, to study photography in 1990. After settling in London in 1992, he would call the UK capital his home until 2011, apart from a hiatus in New York. Today, he splits his time between London and Berlin but has a house on Fire Island and frequently travels the world as an artist, DJ, singer, record producer, and architect – and, of course, as a photographer.

Exhibition installation of "Pairs Skating: Boris Mikhailov and Wolfgang Tillmans"

As cursory as this biographical sketch of Tillmans’ beginnings may be, it nevertheless has many elements that can be found in his work throughout the decades. (Beginnings are never arbitrary.) His early work was often reduced to being but a chronicle of the dilated pupils of Gen X ravers and their drug-fueled search for utopia, but his world was already vast, full of still lifes of tomatoes and eggplant at the edge of a pool, plus images of synthesizers and chairs and Pride parades and demonstrations and operation theaters and blueberries. Staged images show up: the famous one of his childhood friends Lutz Huelle and Alexandra Bircken sitting semi-naked in a tree; and others, wherein Lutz mimics doggy style on Alex (both are dressed) atop a laundry detergent display, while three friends react variously to the make-believe scandal in Supermarket (1990).

In Tillmans’ early works, his many friends and compatriots are everywhere, cuddling in camouflage on a beach, at home after parties, and naked in a park. His aim, in the beginning, was “to somehow represent what was not being represented,” as he told The Guardian, and the resulting images depict “a kind of freedom that was not being expressed honestly elsewhere.”

What’s remarkable is that the intimacy, immediacy, and seeming casualness that his known and unknown friends exude can also be felt when he turns his lens to the world-famous – Aphex Twin and Isa Genzken and Wu-Tang Clan and Nan Goldin and Richie Hawtin all feel just as relatable in his pictures. This is because Tillmans is nonhierarchical while he nimbly moves between worlds. No one is better and no one is worse. He has photographed himself, Damon Albarn, and Frank Ocean in the shower, and had Michael Stipe and Kate McQueen sit in the same green chair that a mohawked young man pisses on in another photograph. (Whereas McQueen almost assuredly didn’t sit in the young man’s urine, as her photo was dated 1996, the same cannot be said of Stipe, because his and the young punk’s photos are both dated 1997.)

A choreography of works by Tillmans and Mikhailov. Photo: Oleksandr Osipov

In 1998, Tillmans felt like the world was already “over-photographed,” though that attitude didn’t lead to him quitting the medium before the dawn of selfies. Instead, he started to explore abstraction as a way to slow down and counteract the cultural inundation of images. One old idea he picked up was his “Faltenwurf ” series, begun in 1989, in which he shot the compositions of unused, discarded, or drying clothing on radiators, chairs, or stairs, for instance, calling attention to the ways the garments drape or fold.

This sculptural aspect of his practice also found expression in his “paper drop” series (begun in 2000), in which a sheet of paper bends and casts shadows after being dropped – a meditation on materiality that was not representational in intent, though these works sometimes resemble drops of water if you rotate your head 90 degrees. This practice was not a turning away from representation, necessarily. As Tillmans told Hans Ulrich Obrist, “I’m interested in what the representational and the abstract have in common, not what separates them.”

Later, landscapes take greater precedence. Tillmans might simply present the weirdness of the world we live in, as with red lake (2002), which raises many questions about the depicted rust-colored water, which looks toxic; or he might make an ice storm so dreamy that you wonder whether he isn’t partaking of Mikhailov’s sandwiching technique. Tillmans’ unpeopled landscapes also say much about the human world. Some images of the sea, for instance, are rife with politics – such as Italian Coastal Guard Flying Rescue Mission off Lampedusa (2008), which has often been misinterpreted as relating to the refugee crisis (an interpretation Tillmans suggested, at the Hamburger Bahnhof, that he didn’t have a problem with), or the famous The State We’re In, A (2015), which has been widely interpreted as a commentary on its political times – before the Brexit referendum or Trump’s first presidency. These interpretations might stem from the fact that Tillmans has incessantly lent his lens and voice to many of the day’s burning issues, ranging from the AIDS epidemic and Black Lives Matters to LGBTQ+ rights, environmental causes, and refugee crises, even as he also campaigned widely against the Brexit referendum and the AfD in Germany.

Pairs Skating: Wolfgang Tillmans and Boris Mikhailov exhibition view

Even when the subject matter isn’t overtly political, Tillmans’ photos are infused with the politics of the everyday through a highly personal, observational, and democratic approach to image-making that elevates what is typically left unseen. Friends lounging in messy kitchens, people playing cards on the streets in Hong Kong, and women at marketplaces in Ethiopia all exude the inherent worth of human life, no matter how marginalized or vulnerable. As Minoru Shimizu writes in an essay accompanying Truth Study Center, “Tillmans’ political principle is not the principle of difference or identity but the principle of ‘sameness.’ He does not see every person as different but views (not identifies) each arbitrary entity as being equivalent to and the same as every other arbitrary entity.”

By now, the reader will have probably formed some notion of why Mikhailov and Tillmans could be exhibited together. Some keywords might be nakedness and intimacy, social and political commentary, and experimentation. They come from vastly different ages and societies, and we could apply many binaries that have shaped their outlooks and their lives, including East versus West, socialist and post-socialist versus liberal and consumerist, straight versus gay, economic hardship and class issues versus identity politics and environmentalism, and so on. They also have different aims.

During the February conversation at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Mikhailov suggested that he tries to create paintings, yet he admires Tillmans’ resistance to this approach. Tillmans replied that he is grateful to have grown up much later, having never felt the need to paint his photographs, unlike, say, Gerhard Richter. A related difference here has to do with narration, with the accumulation of images in exhibitions or books. Whereas Mikhailov works on a single theme that becomes more nuanced with each image, Tillmans creates poetic networks of meaning with his books and composition-like installations, which blend the abstract with the representational on postcards, A4 sheets, and large-scale prints. All that said, the two artists are being shown together for one glaring reason: both Mikhailov and Tillmans use photography to show the lives of common people, capturing the complexity and fragility of the human experience, its simple magnificence. Such a project, I imagine, has the potential to be a breath of fresh air in war-torn Kharkiv.

Early works by Wolfgang Tillmans. Photo: Oleksandr Osipov.

Another way to write about an exhibition you haven’t seen is to think yourself into the space. From April 25 to September 28, 2025, the exhibition “Pairs Skating: Wolfgang Tillmans and Boris Mikhailov” is to be presented at the YermilovCentre, which is named after Vasyl Yermilov, a famous avant-garde artist, pioneer of design, and Kharkiv native. The center was established in 2012 and is located in the basement of Karazin University, making it “one of the safest places in the city,” according to co-curator Kochubinska. Upon arriving at the YermilovCentre, you stand on a balcony that overlooks the subterranean exhibition space. To the left will be some of Tillmans’ works, to the right will be Mikhailov’s, and in the center their bodies of work will be in dialogue with each other, speaking through formal, gestural, and color relations.

Mikhailov and Tillmans have worked together intimately in making their final selections, and an emphasis was placed on the male body, which is “a highly contested topic in Ukraine,” co-curator Isserlis suggests, because “the male body doesn’t belong to men anymore.” Men of serviceable age can be drafted at any moment, so their bodies always potentially belong to the state. For Isserlis, “It is very important that the body is seen as a subject and not an object.”

On the floor below, Tillmans shows The State We’re In, A, which depicts the surface of the Atlantic on a gray day. The ocean seems close to “erupting” and has “all these different subwaves dancing and fighting against one another,” as Tillmans mentioned at the Hamburger Bahnhof, hinting at the political interpretation suggested earlier. But for Tillmans, the photograph is also about the “illusion of strict borders.” At the most distant point in the image, you cannot divide the sea from the sky; you never arrive at the horizon. Borders also get addressed in Mikhailov’s work on this floor, where he shows images from various series that were shot in Crimea, the region that Russia annexed in 2014.

According to Isserlis, this is a political statement: “We still consider Crimea to be a part of Ukraine; we’re not letting it go.” Kochubinska added that Crimea was always important to the residents of Kharkiv, as “it’s a gray city with no big source of water.” The people of Kharkiv vacationed in Crimea until they could do so no longer: “It was a place of freedom that permitted you to be yourself with all your weaknesses.” This floor also includes a space showing videos by the two artists, meaning that they are both together and alone on each floor. Taking everything together, the exhibition embodies the title “Pairs Skating” as much as it doesn’t. Derived from the discipline of figure skating, where two people “perform their movements in such harmony with each other as to give the impression of genuine” unity, the title suggests that Mikhailov and Tillmans glide together, which I imagine they will, over the thin ice of contested subtexts. But, given the space granted to each, I imagine they will demonstrate their own grace and beauty as well.

Exhibition installation of "Pairs Skating: Boris Mikhailov and Wolfgang Tillmans"

Another way to write about an exhibition you haven’t seen is to speak to the artists to uncover their motivations and desires and feelings about an exhibition that they themselves might never see.

SHANE ANDERSON: What’s it like doing a show you will not attend?

WOLFGANG TILLMANS: I actually did a show in Tokyo, during Covid, where I installed remotely with a model. I’m quite used to working with a model, and I feel confident that I can achieve what I want to achieve in Kharkiv. I don’t feel like this is a compromise. I put myself into the space at the YermilovCentre, and I feel like I can adapt to whatever situation we’re going to meet. It’s a huge privilege to be able to do this after three years of vocally advocating for, and extensively donating to, the Ukrainian cause. Three years, where I’ve also been hosting Ukrainian art events at Between Bridges [Tillmans’ foundation, established in 2017, which supports the arts, LGBT+ rights, and anti-racist work]. We did a Ukrainian community center in … winter … [20]22–23, and then we hosted the Ukrainian Biennale in 2024, for instance.

I always stayed shy of going [to Ukraine], though. I didn’t want to stand in anybody’s way. I want to be useful, but there’s no need for me. I’m not a war photographer. There are people who are much more competent at that. As for art exhibitions, there had been invitations to Lviv, but that city’s the farthest away from the arena of war, and so it didn’t feel as urgent. I’m really happy that there’s now a way where I can [be useful], and where it’s clearly wanted and needed. Even if it’s with my work and not my actual person.

SA: What does this exhibition mean to you personally and/or politically?

WT: In a world of multiple conflicts and wars … we all have limited capacity to equally and even-handedly spread solidarity to all those affected by war and violence. But since February 2014, and even more acutely since February 2022, I have felt very strongly that it must feel very unjust to be invaded by your neighbor – and in what I believe is an entirely unprovoked way. Ukraine didn’t have an agenda of aggression. Nobody has or had any intention of attacking Russia. All this talk of Russia being existentially threatened is ridiculous. It is one hundred percent clear that this is a neo-imperialist war.

Three years ago, my eyes were completely opened to something that we were fairly blind to in West Germany when I was growing up in the 1980s – namely, that Eastern Europe was under an imperialist Russian occupation, the Soviet Union. When we were growing up, we only heard about American imperialism. I feel incredibly grateful to the Ukrainian people who are reluctantly fighting in this war – again, they didn’t want it – because they are literally fighting it for the rest of Europe. They’re showing that just because you live in a so-called sphere of influence of a larger country, it doesn’t mean you should shut up and subjugate yourself.

So, for me, exhibiting there meant thinking about what is maybe missing. The question I always ask myself when exhibiting in a city is: what would be interesting there? What am I interested in showing right now?

Boris Mikhailov, Berdyansk, Beach, 1981 © Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov and Barbara Weiss Galerie; courtesy of the YermilovCentre and RIBBON International.

SA: What will you be showing?

WT: My choices were guided by picking work that doesn’t speak of war, as such, because my sources told me that they don’t need more work about war. In the dialogue with Boris and Vita [Mikhailov, Boris’ wife], they encouraged me to include four works of a more fragile sense of masculinity. The hardness and softness of some of the works from the early 90s stemmed from a time when I was still personally working through a late-80s feeling of the military presence and potential threat of war that I grew up with in my late teens. The masculine hardness and fragility found a new expression in the early 90s in the happy, loving, hippie attitude that co-existed with the hardness of techno and the martial, camouflage looks of the time. Boris responded to how I portrayed that. The sentiment in those photographs is something he acutely felt. Due to last year’s constant recruitment, every man of service age in Ukraine could be randomly taken off the street, which means that no man really owns [his own body].

Another work of mine that was high on the wish list of the curators was The State We’re In, B. It dates from 2015, and I gave it that title at the time with a certain sense of things to come. The unsettling, charged ocean surface is about to erupt, and most likely not in a pleasant or controllable way.

These works don’t really stem from a consideration of Kharkiv as a city but [instead] from the point of view that I never had an exhibition in Ukraine. So, this is also an introduction to the audience, showing some classic works and new works.

And, of course, this dialogue with Boris is fascinating, because we have never collaborated. We’ve never had a dialogue between the two of us directly. Even though we live in the same city since I moved to Berlin in 2011, we hardly ever see each other. And yet, we’ve appreciated each other’s work for a long time. There’s been a lot of mutual respect. It’s been a real pleasure to work together and speak together more.

SA: What do you see in Mikhailov’s work? What attracts you to it?

WT: There is a deep love for life, and there is a nonjudgmental gaze. Even though, of course, one could see his most famous works of homeless people as his most controversial photographs – many [subjects] appear to be too out of their mind to be consenting to be photographed – I still feel that there is a warmth there, there is respect coming from Boris’ willingness to engage and seek out the proximity of these people. He doesn’t keep a safe distance [from] his sitters. I think that’s because he loves life and people. In order to translate that closeness, you as an artist have to get close. Photography, of course, implies a physical distance between the camera and the subject, but I think you can speak about this proximity in more general terms in art. If you’re a writer or poet, you have to somehow get close to what you’re talking about. Sometimes, that is uncomfortable or messy or out of your control. And for Boris, it’s never a performative risk to himself. He hasn’t gratuitously exposed himself or others. I mean, these photographs of the summers in Crimea, of these spiritual communities on the Black Sea, are about moments of life and death and birth. He went there because he felt close to life and not because he wanted to perform.

The same set of questions was posed to Boris Mikhailov via email, as we do not share a common language well enough to speak freely, and I received the following response (lightly edited for clarity).

BORIS MIKHAILOV: In my long life, there have been many occasions when I could not attend my own exhibition. These were because of visa problems or illness or …. For me, the main thing is to prepare an exhibition – i.e., to decide what is important to show and how this decision can best be realized in the proposed space, which, in this case, I know well. At the same time, it is also important for the artist to see, feel, and make corrections during hanging; that way, the exhibition is filled with his living energy. I have not given up hope that I will go home; that I will be at the exhibition, which was conceived as the benevolent message from two artists to the citizens of my long-suffering city of Kharkiv, to which I owe a lot and am eternally grateful …. This exhibition has been made for the citizens of Kharkiv, for Ukraine, and for memory. Maybe it isn’t all that important if we are somehow unable to attend it. The main thing is that it exists!

The exhibition will feature some new and old works of mine, works I haven’t shown often, if at all, even though they are very symbolic for me and my work, even now. One part of my exhibition will be the works I shot during different times in Crimea, on the shore of the Black Sea. There’s a free-floating hang glider, a series with a child being born in the sea, and photographs of naked male and female bodies, connected by some sense of primitiveness and naturalness to the landscape and the mountains. It’s almost as if the nature makes this natural nudity permissible.

This exhibition is a very interesting coming together where you can see something that isn’t visible.

The exhibition “Pairs Skating: Wolfgang Tillmans and Boris Mikhailov” is on view at the YermilovCentre in Kharkiv, Ukraine, until September 28, 2025.

Credits

- Text: Shane Anderson