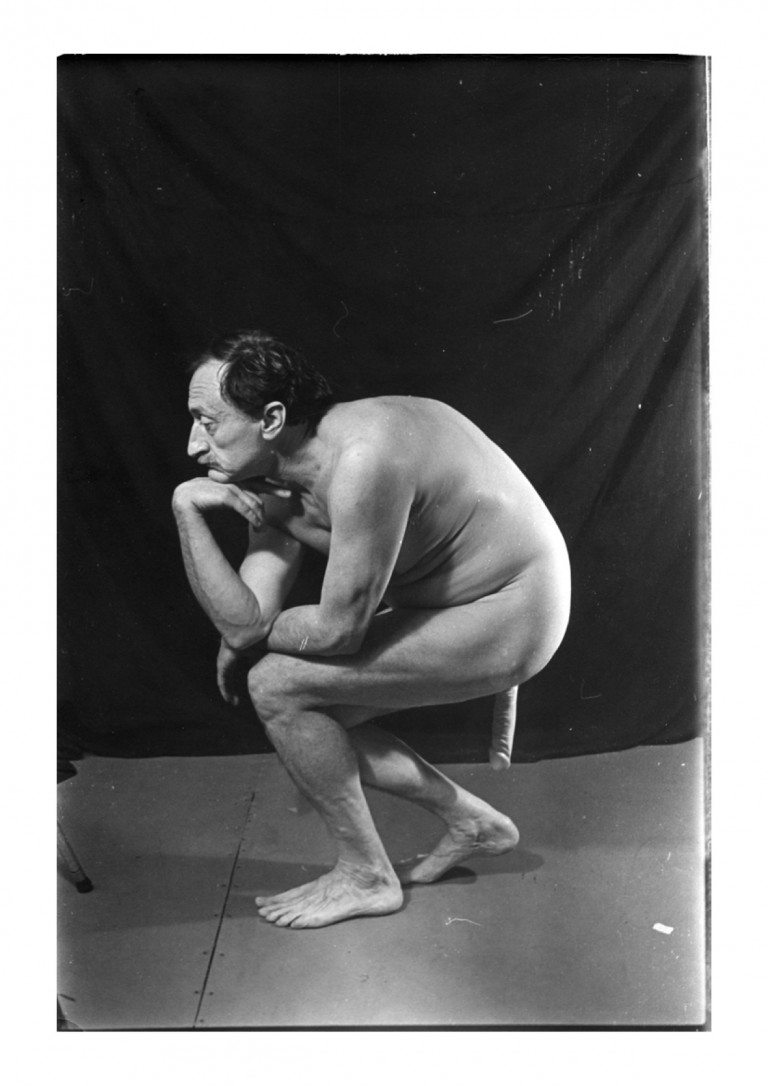

Hero, with Dildo: BORIS MIKHAILOV’s Nude Self-Portraits

|EMILY FRIEDMAN

One of the former USSR’s greatest art photographers, Boris Mikhailov took to the his studio in 1992 to shoot a gloriously grotesque send-up of the artist-genius, and the empty icons of the newly ex-Soviet Union – presented here in a new book.

“What is truth or not truth?”

In conversation, Boris Mikhailov is prone to rhetorical existentialisms, a fact made clear with the title of his 1992 series of photographs, “I Am Not I.” Born in the Soviet Union, Mikhailov is a largely self-taught photographer. In an ironic foreshadowing of subject matter, he did not officially pursue his hobby until the KGB found nude photographs of his wife and fired him from his official post. This series, published by Mörel Books with an essay by Simon Baker, displays the artist’s intrigue with the naked body’s ability to evoke enigmatic sympathy.

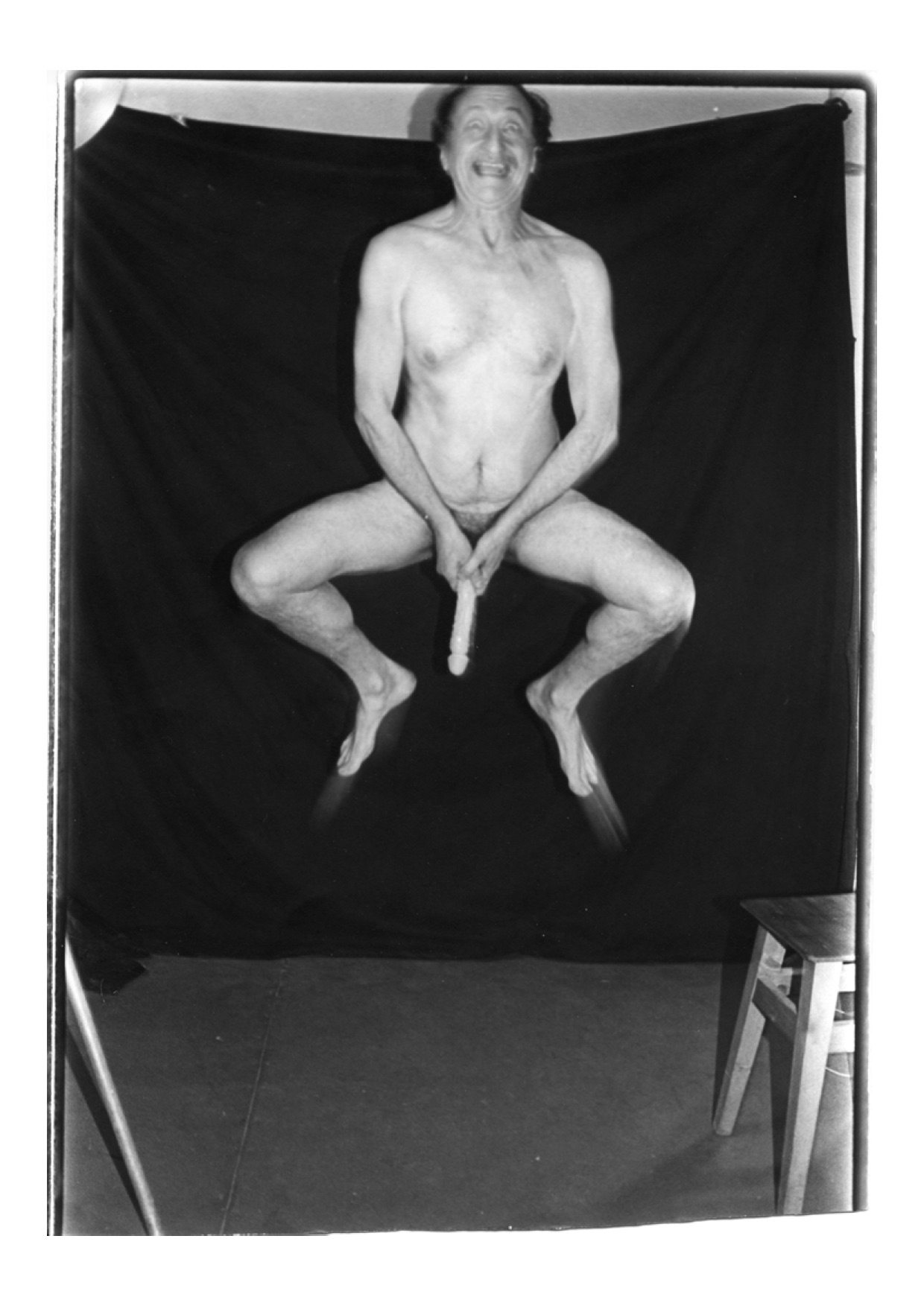

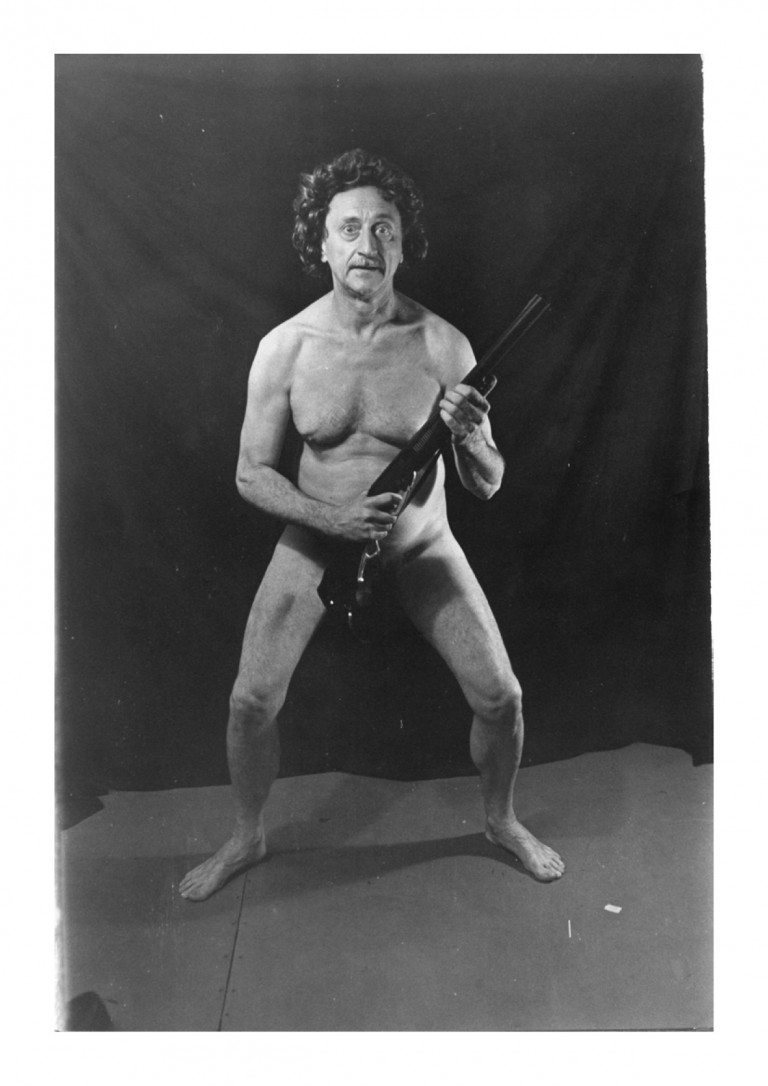

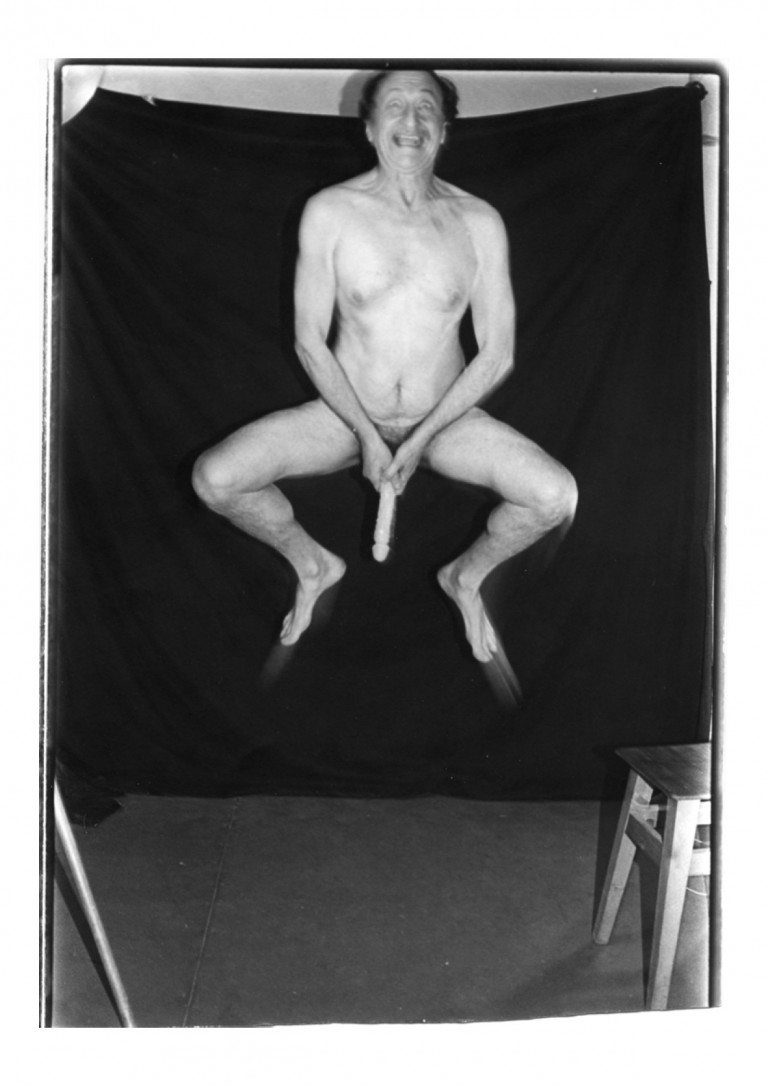

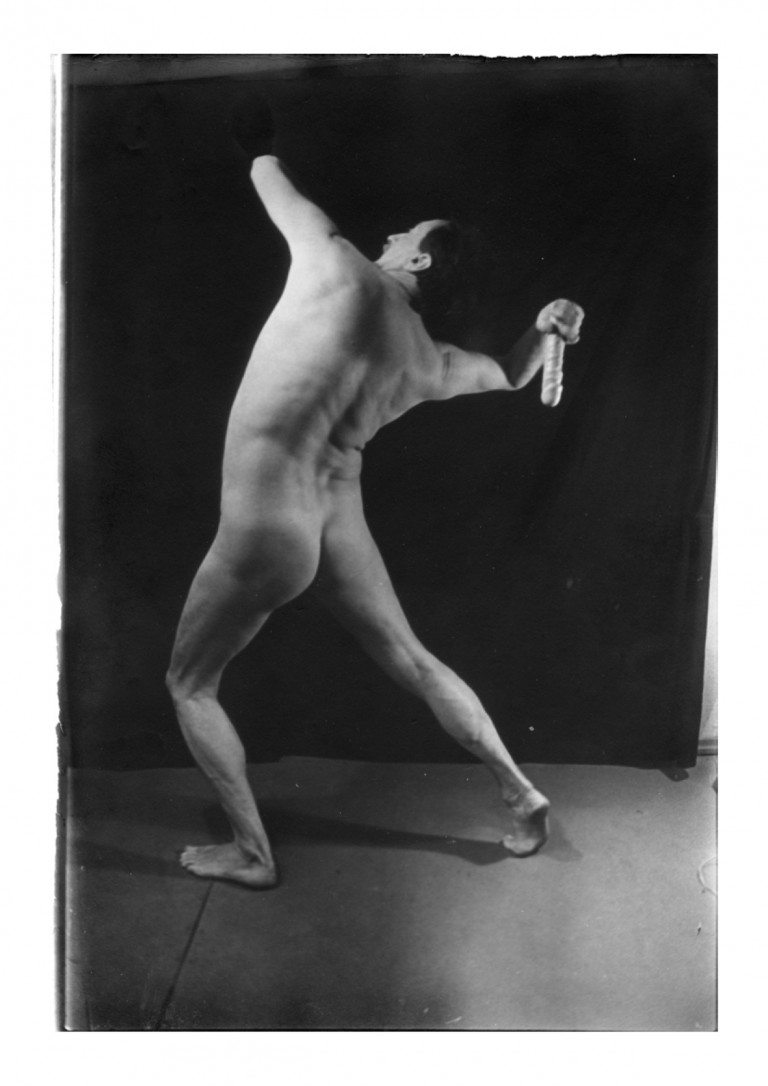

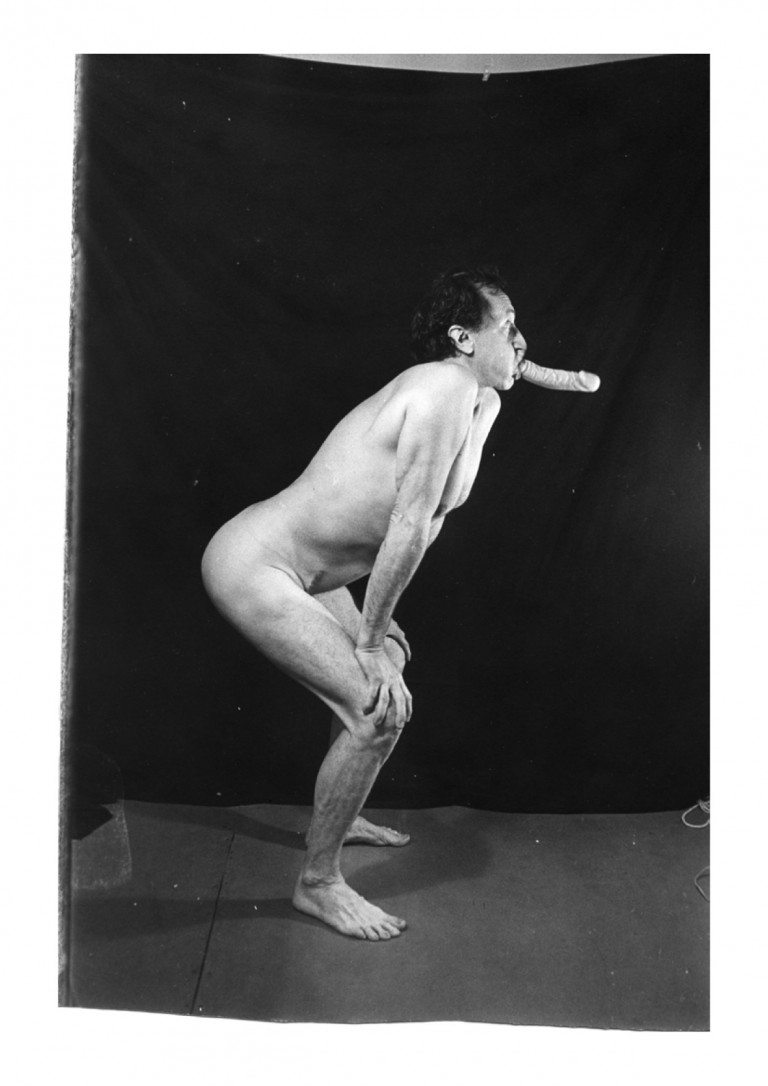

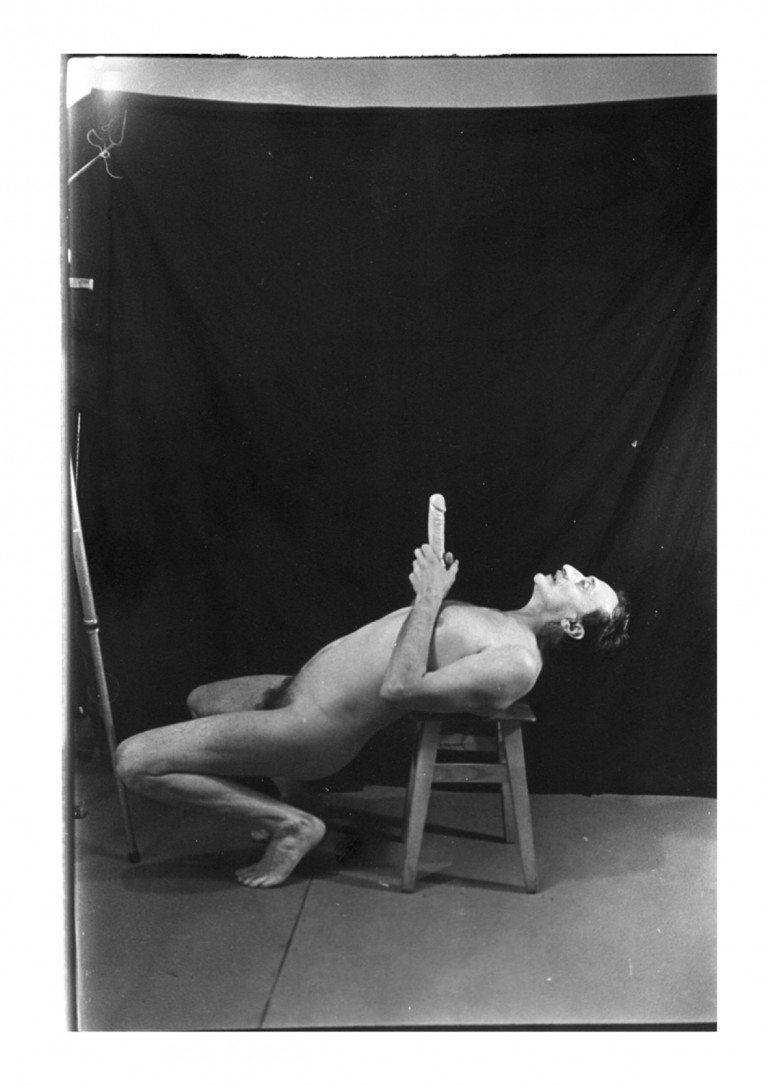

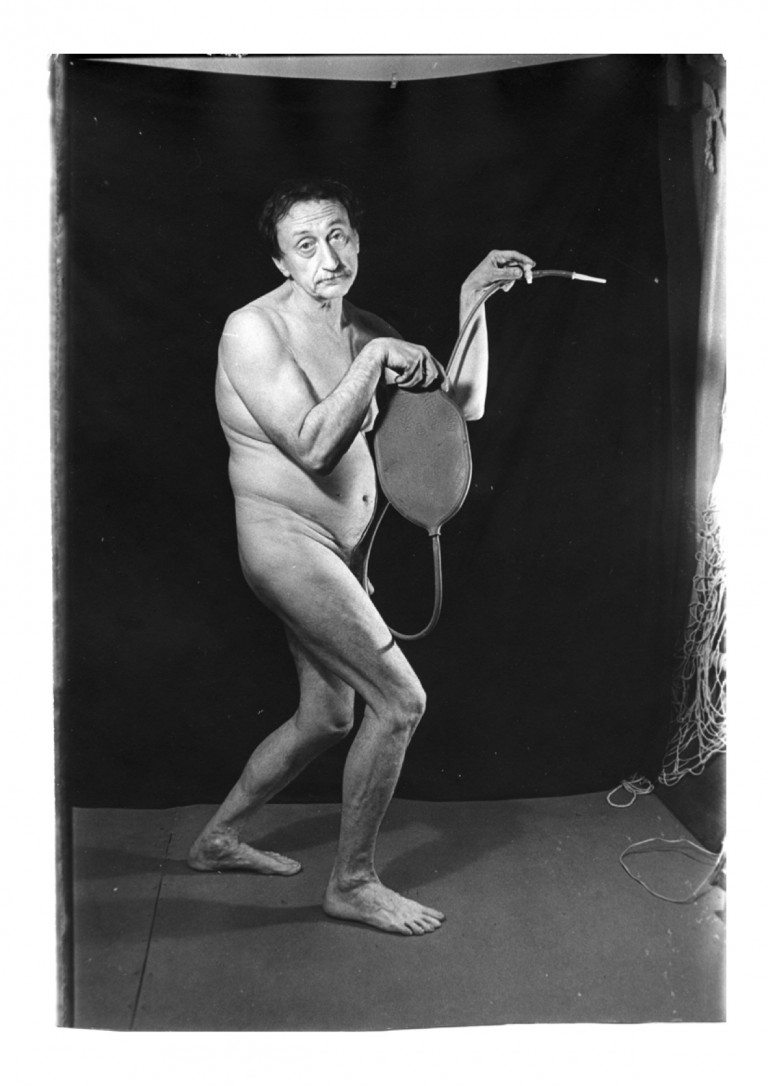

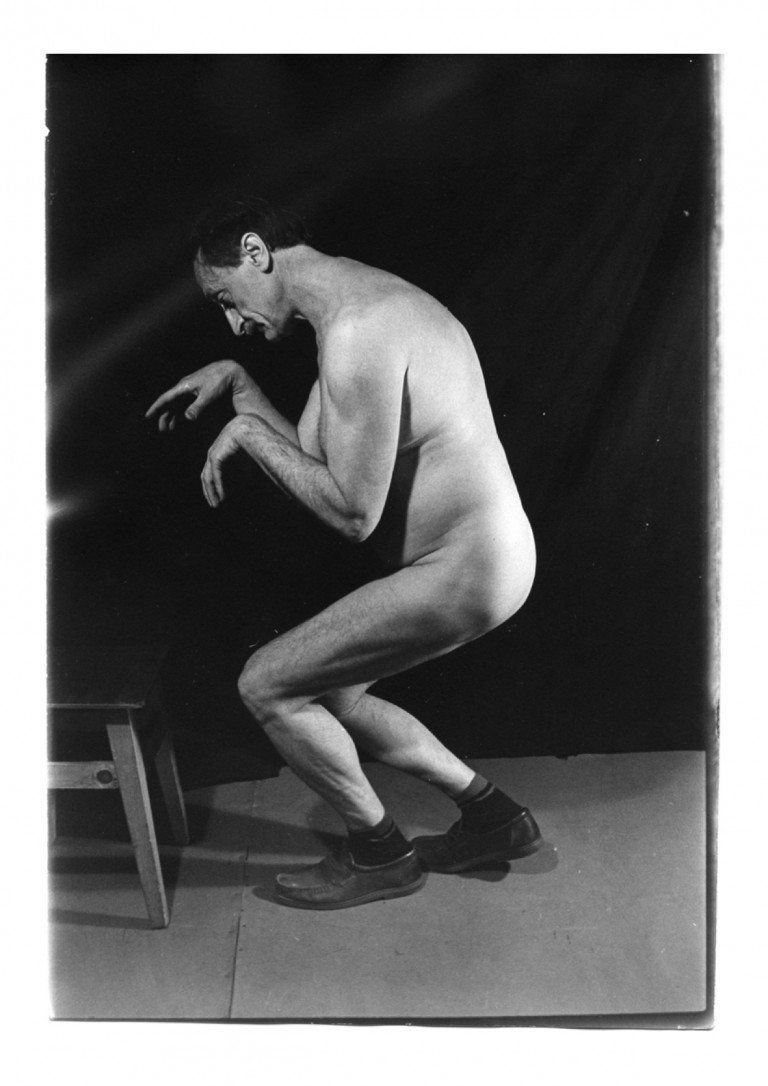

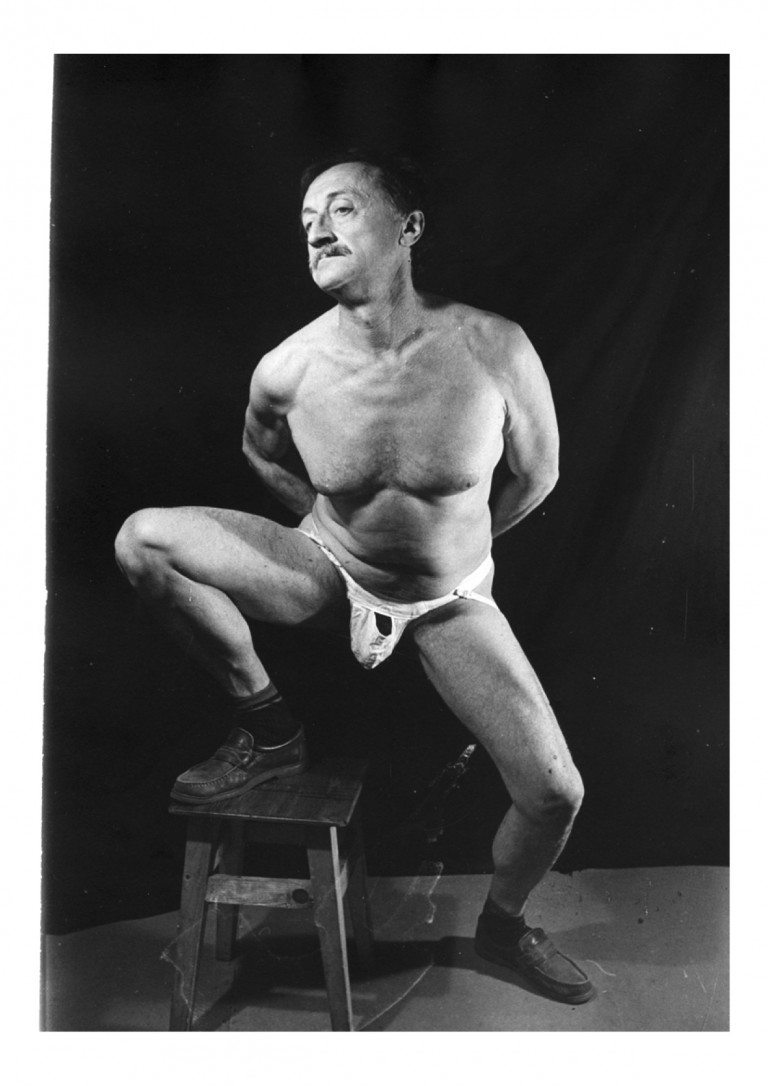

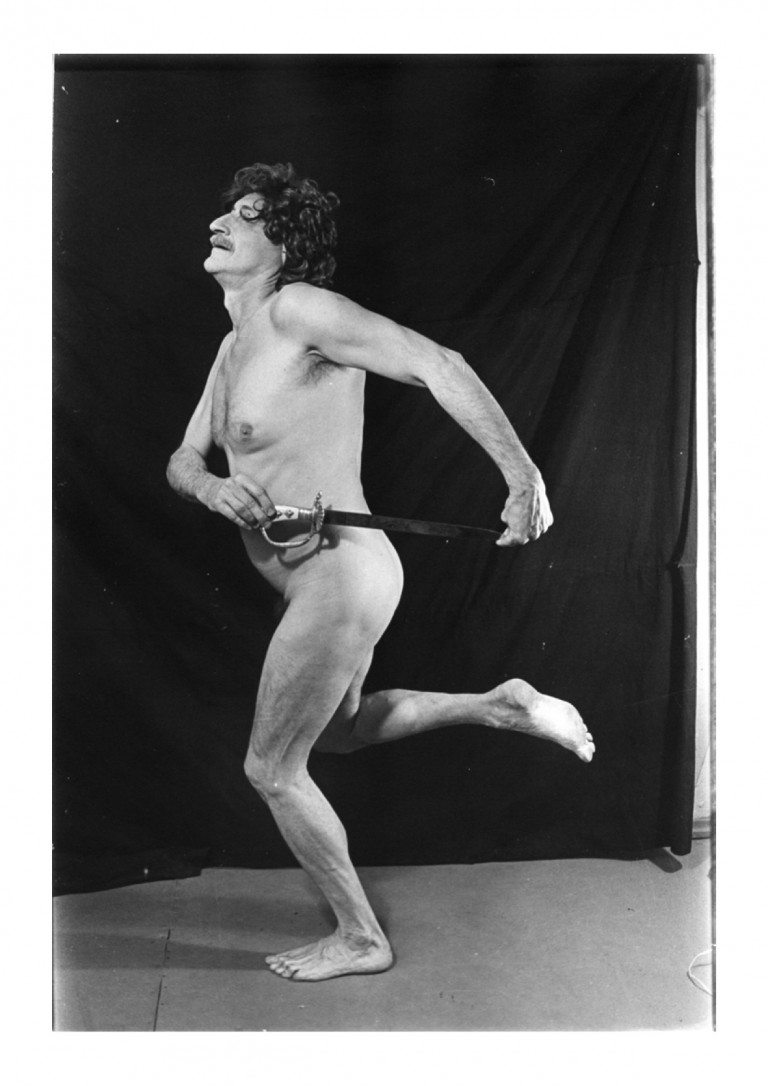

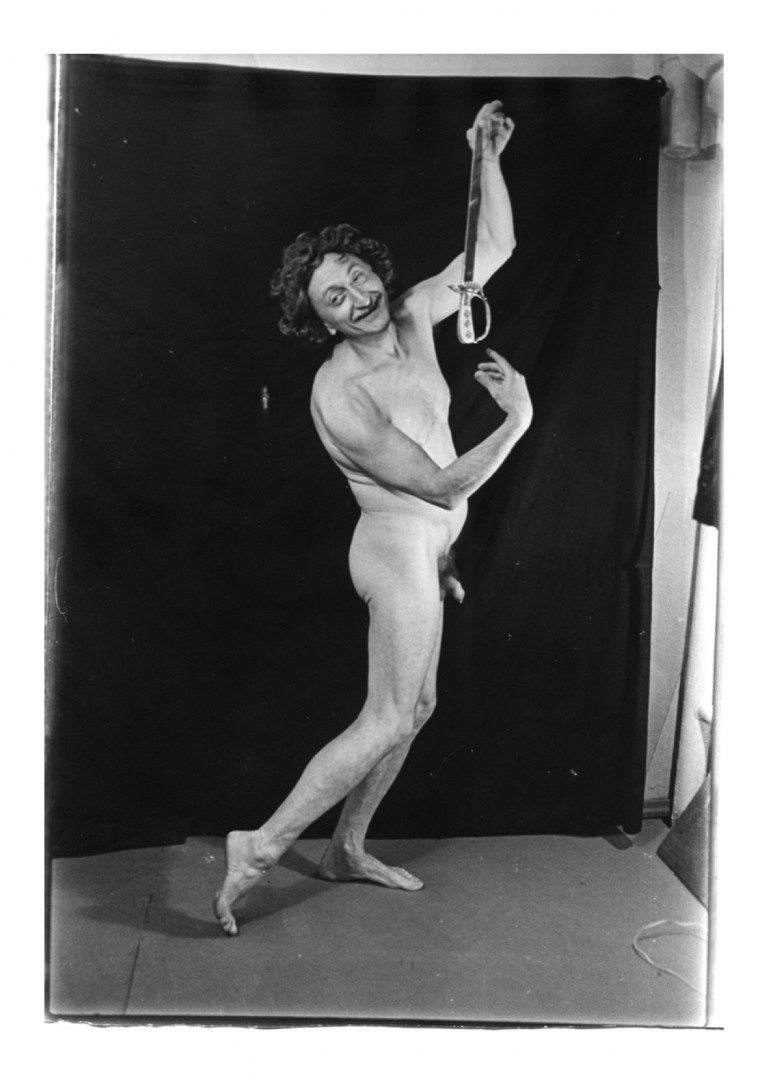

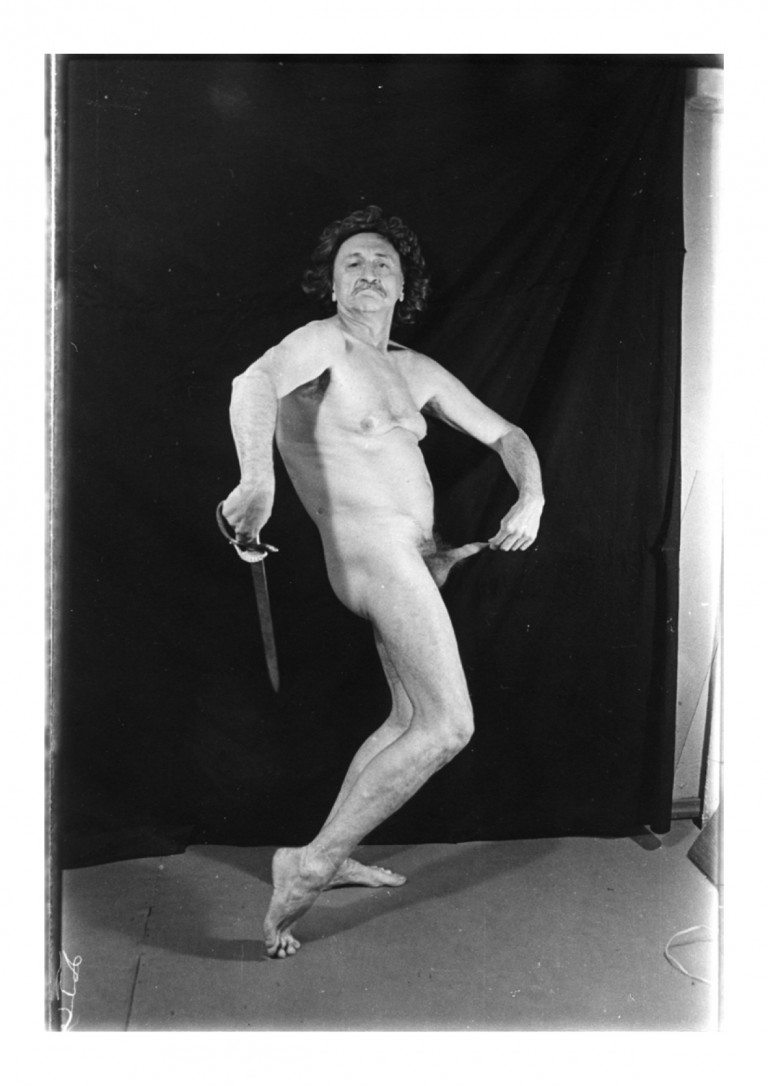

In “I Am Not I,” Mikhailov’s body is alone in front of the camera, where he performs a perverse adagio with props ranging from sword to dildo to enema. The setting is bleak and provisional: flooring nailed together before a black velvet backcloth that cannot cover the entire frame. The sad-clown character of Mikhailov contorts himself into positions of resplendent nudity.

The poses are a grotesque ode to the anti-hero, a theme that recalls his documentary-style work such as the series “Case History” (1997–98), which offered a stage to the homeless of post-Soviet Ukraine. The series pictured groups of disenfranchised figures smiling at the camera, or cowering in the greying snow, often missing limbs and most of their teeth. However, unlike the communal and horrifying realism of those pictured in Kharkov, “I Am Not I” uses comic melodrama to illustrate a solitary form of self-dissolution. In contrast to abject social dereliction, this elegy is a spoof of the artist-genius, wasting away in his studio, playing dress-up with sex toys.

The first six photographs show Mikhailov adorned in a sizable curly wig as he rotates through theatrical postures, wielding his sword as a bizarre phallic surrogate. Yet despite this performance of virility, the self-effacing quality of the work is undeniable. The images embody a dissolution of the ego – the cliché hallmark of an artist’s “late style” – that absolves these images of crude humor by acknowledging the underlying narcissism of the work. In one image, wigless, Mikhailov confronts the viewer directly. Pathetic and morose, he poses with a slumped posture, delicately displaying an enema. The shot reveals a certain motivation behind the preceding images. For it is a crisis of the ego that births the machismo that Mikhailov has chosen to present.

“In the Soviet Union, heroism wasn’t possible. It had already been trashed by ideology.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Spanish poet Juan Ramón Jiménez – a self-proclaimed “martyr of beauty” – dedicated himself to an egotistic search for a Romantic hero, as well as an understanding of the multiplicity of the “I.” His poem, “I Am Not I” was the embodiment of these philosophies, and its reappearance as the title of this series highlights Mikhailov’s artistic principles through inverse, wonderfully crisp dissimilarity. While Jiménez idealized the “misunderstood hero,” Mikhailov has been consistently disparaging of this concept for, as he said: “ In the Soviet Union, heroism wasn’t possible. It had already been trashed by ideology.” In this series, the hero is the punch line. It is a performance, just as Jiménez’s martyrdom appears theatrical and tacky. Heroism is symbolically vulgar, like the physical vulgarity of the naked body before us.

Credits

- Text: EMILY FRIEDMAN