ANSELM KIEFER’s Monuments

|SVEN MICHAELSEN

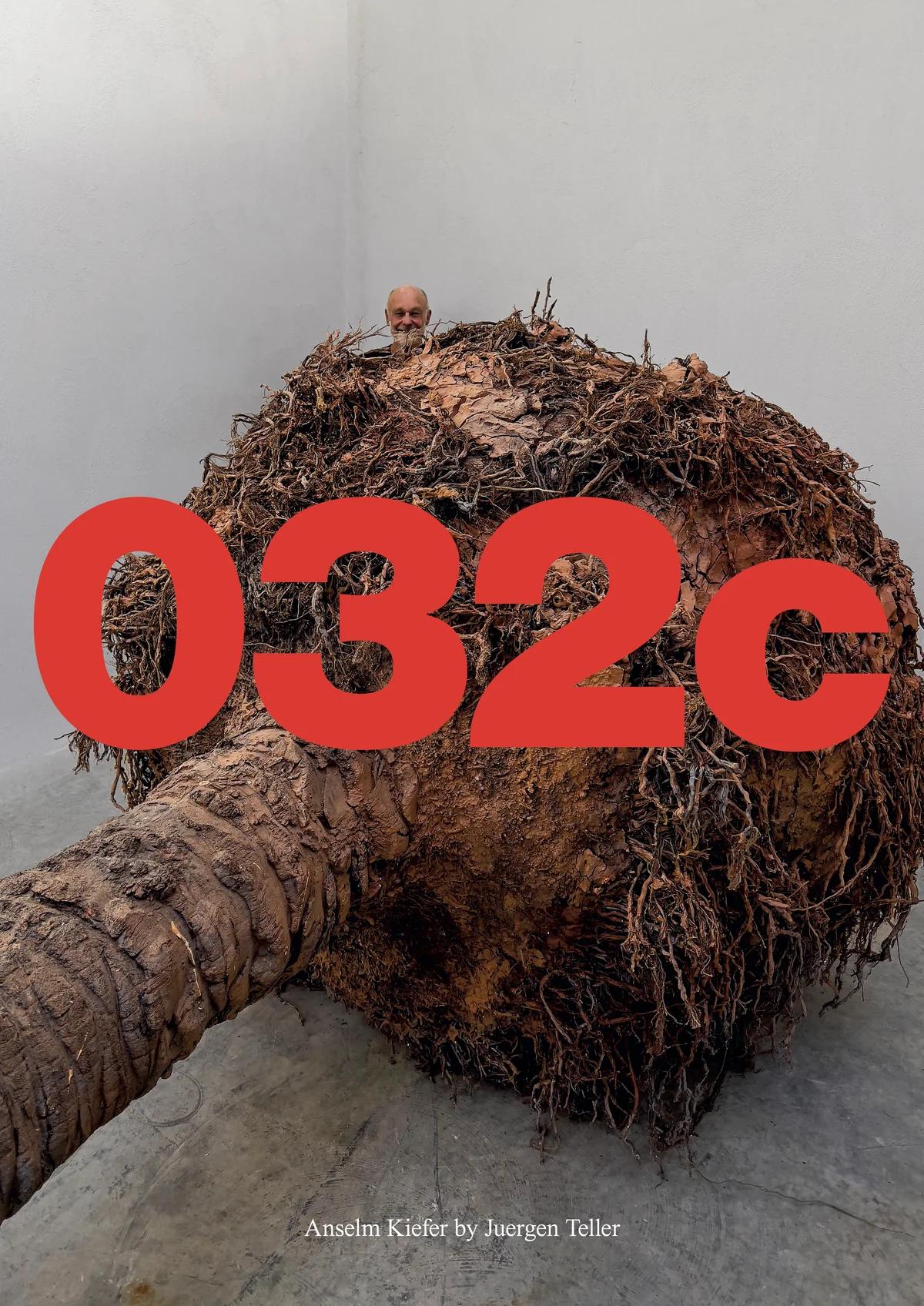

Anselm Kiefer is arguably one of the most important living artists to have left their mark on art history. To celebrate the artist who recently turned 80, the Van Gogh Museum and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam have joined forces for the first time ever to stage a major exhibition of his work.

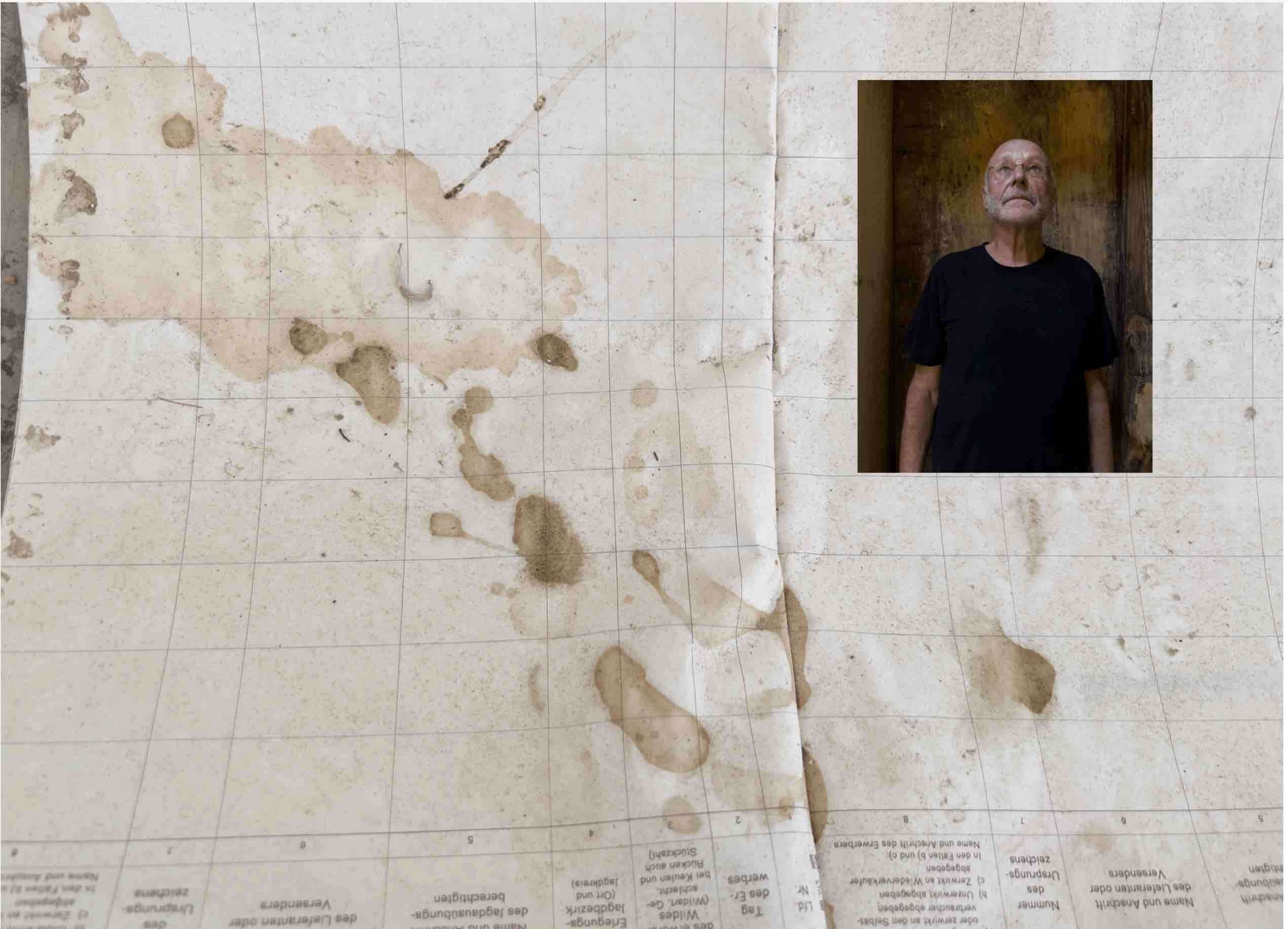

We're republishing our 48 pages print feature with the artist, shot by Juergen Teller and with an interview by Sven Michaelsen, from the sold-out Issue #42 (you can still buy posters HERE.)

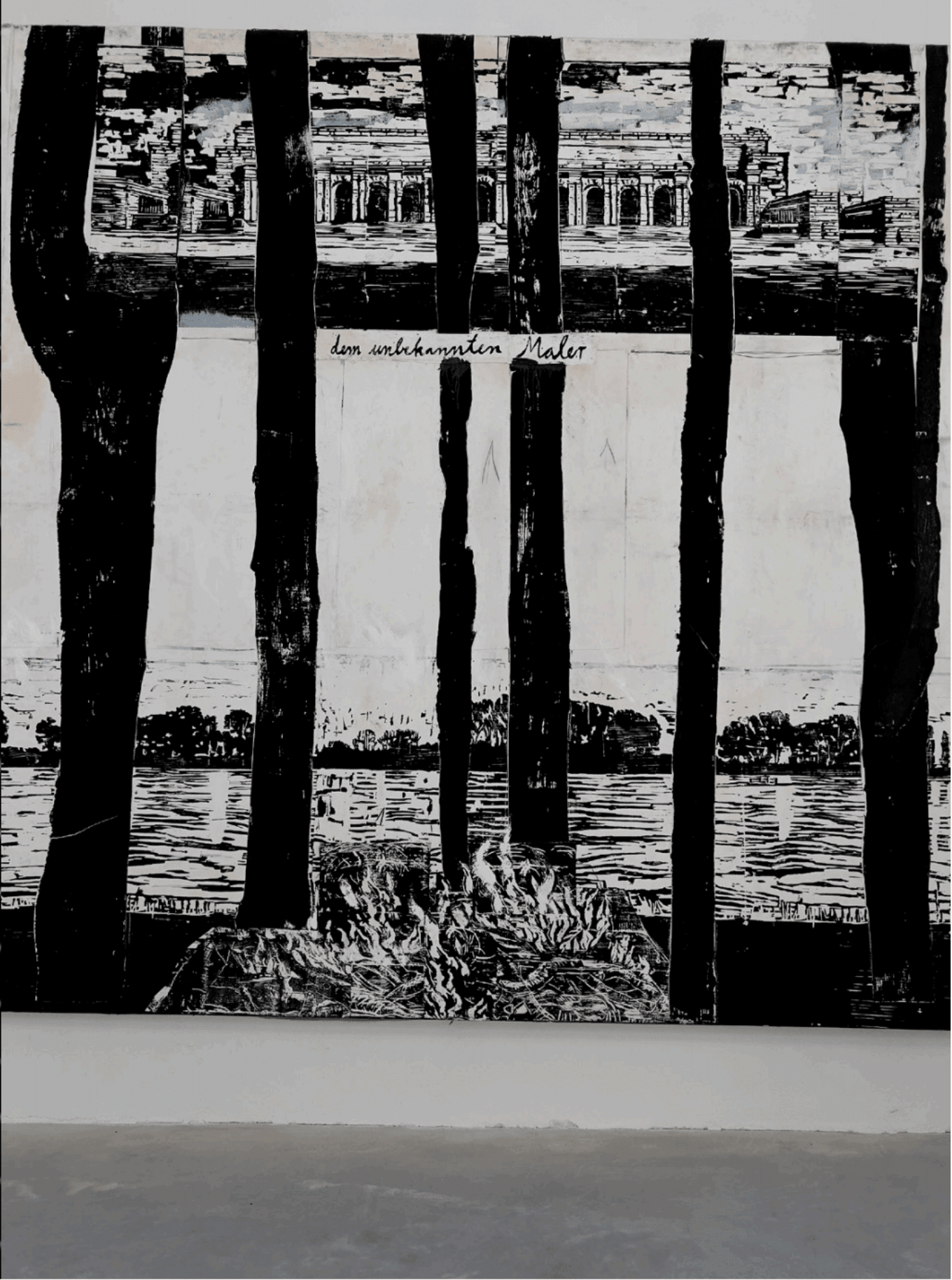

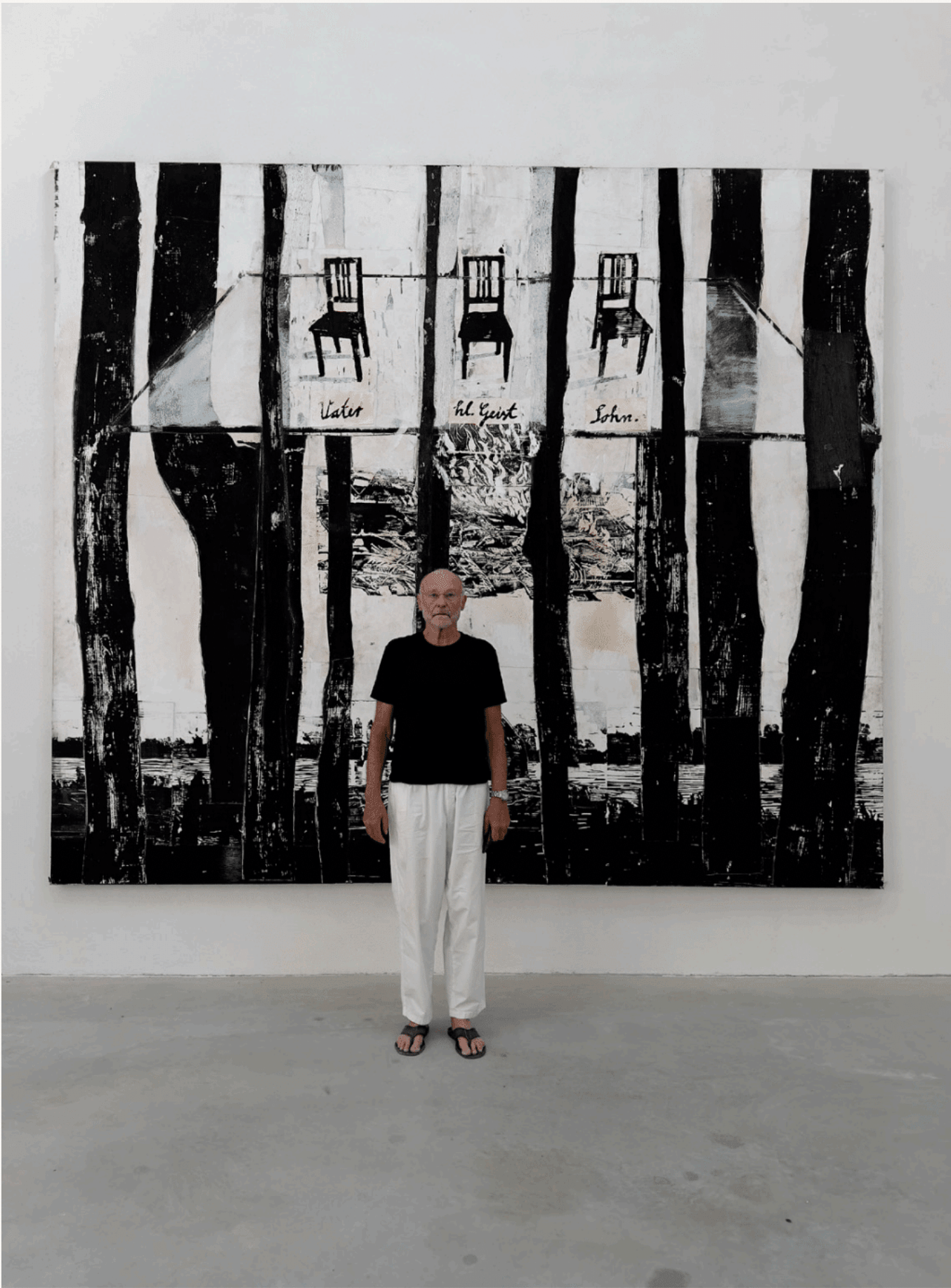

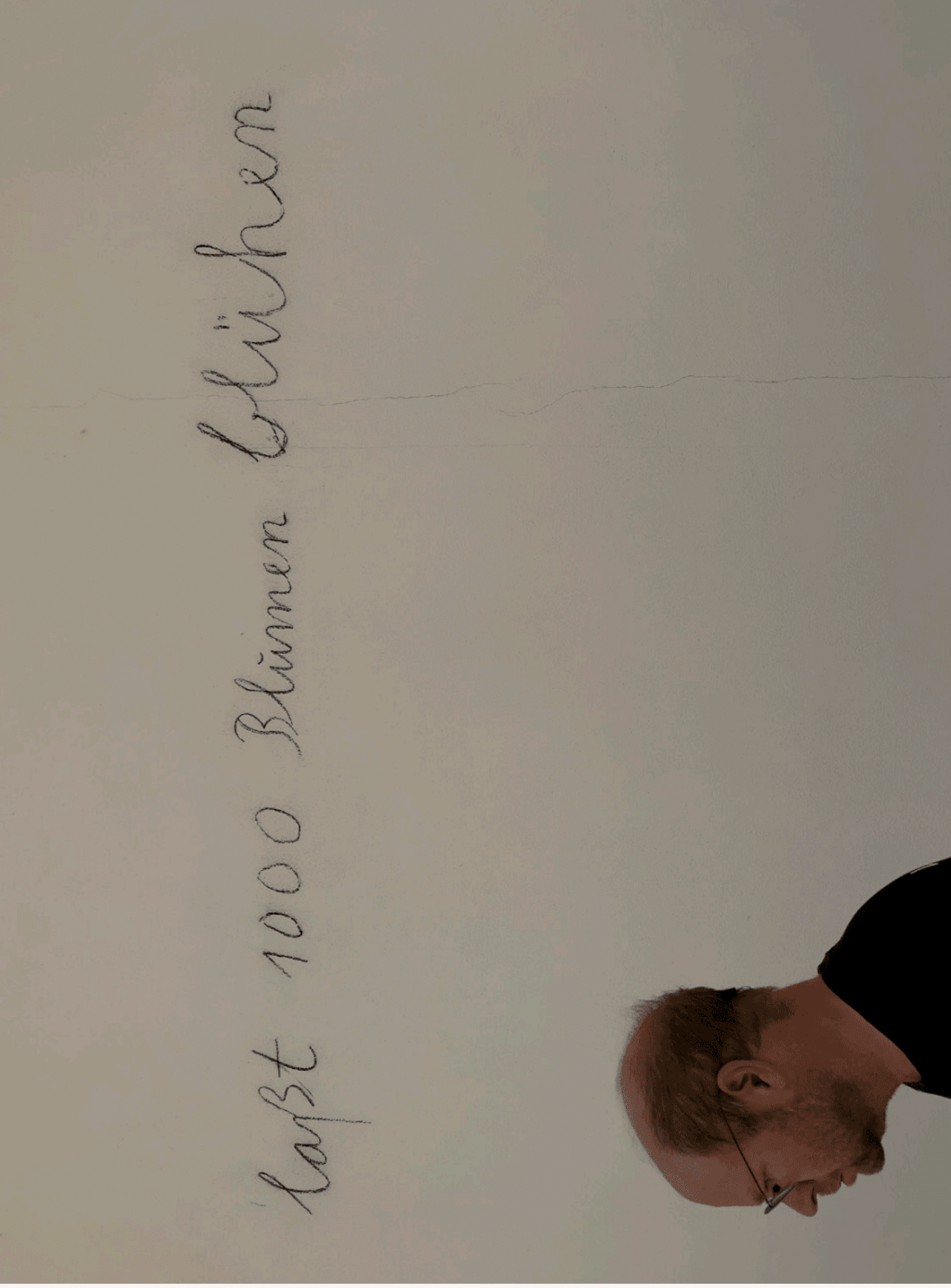

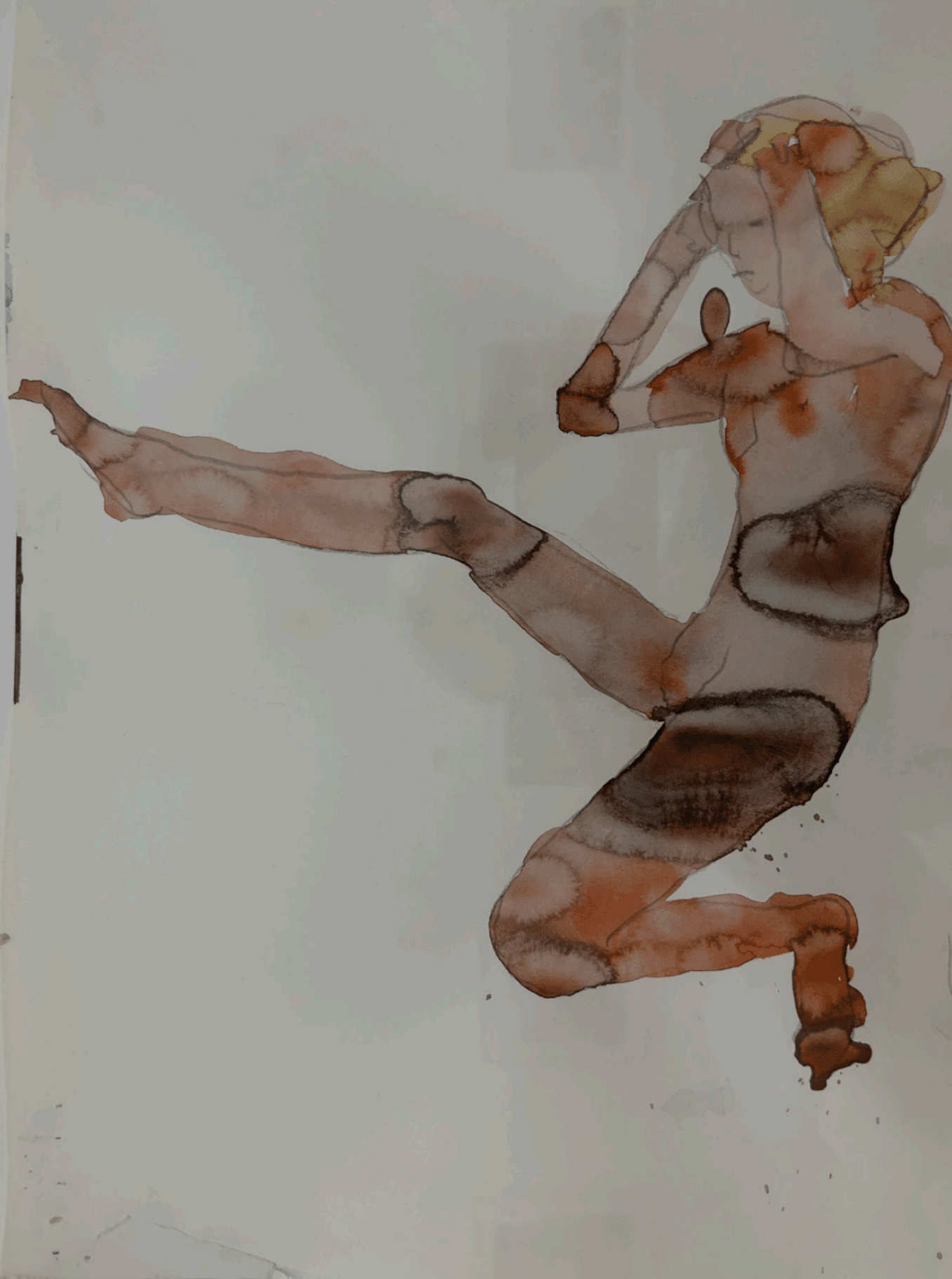

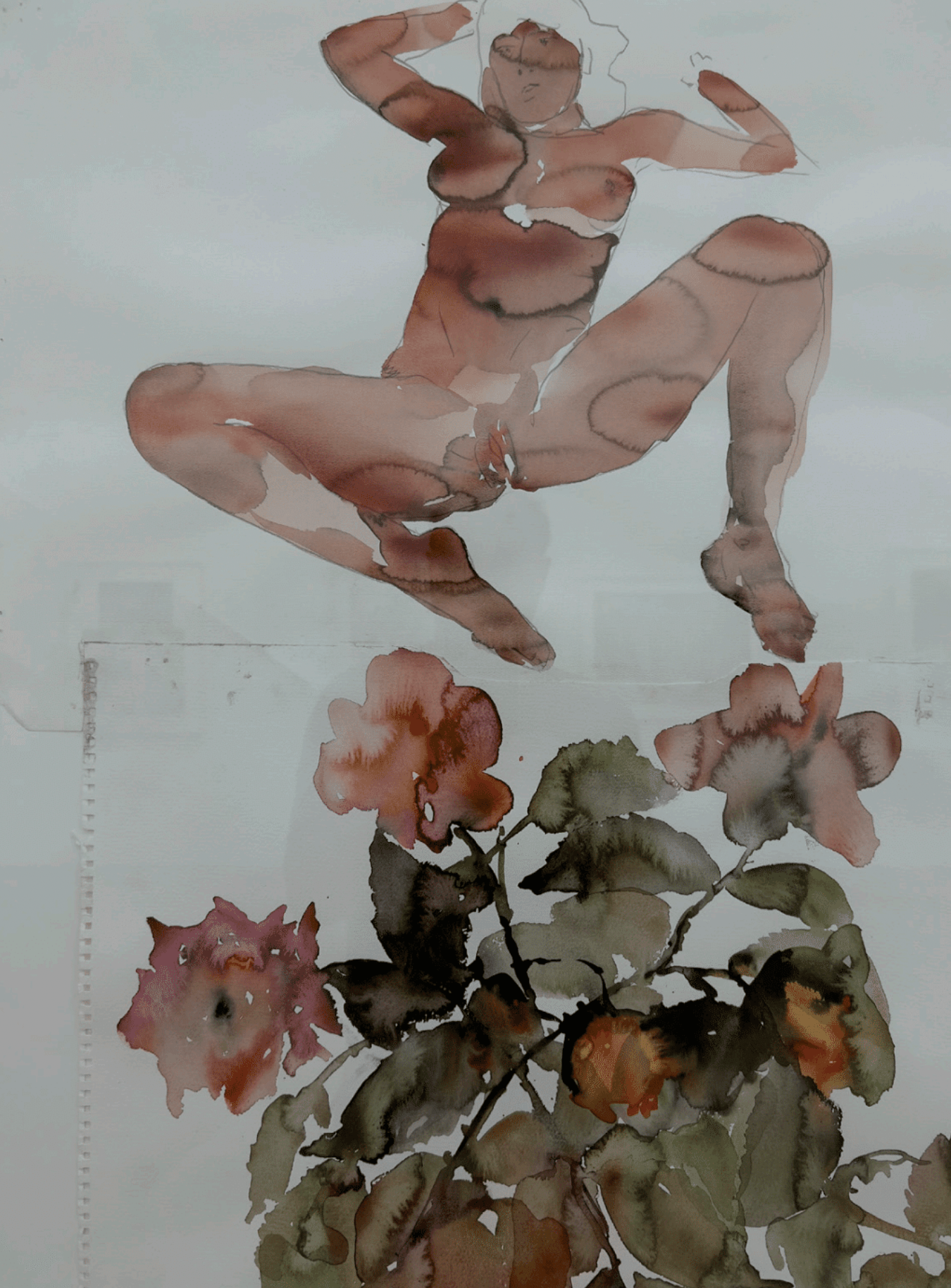

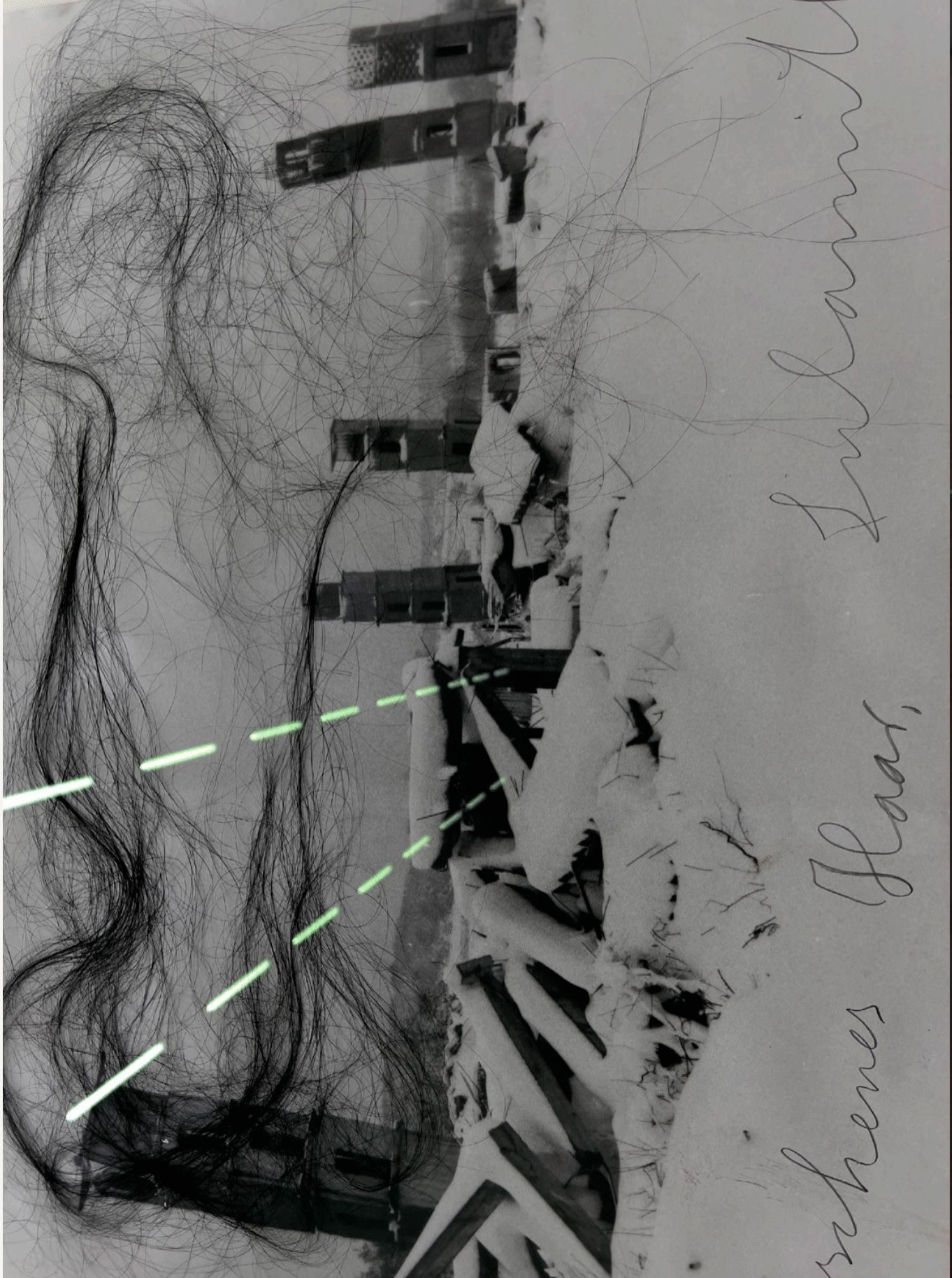

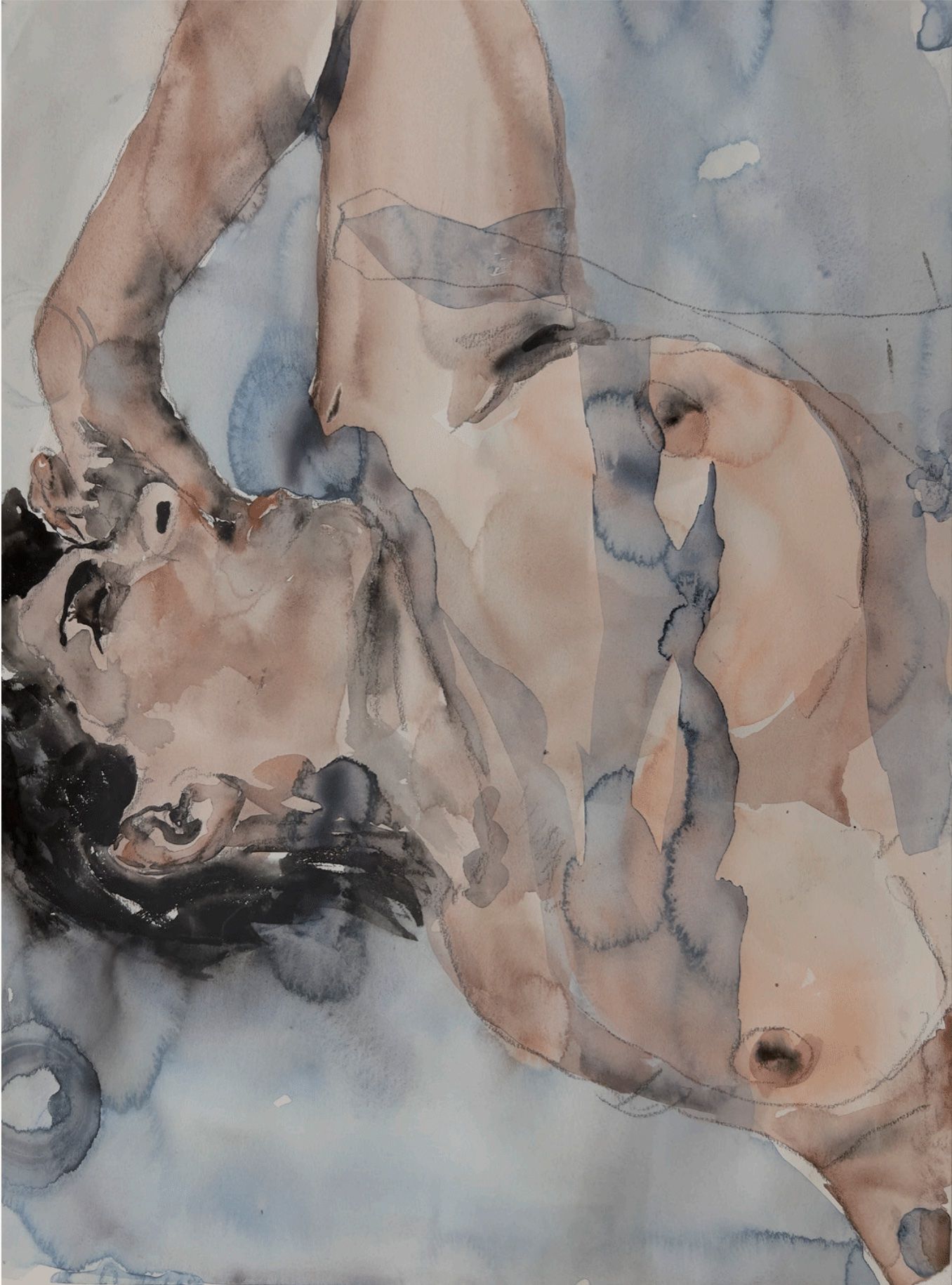

Monuments are materializations of immaterial moments that have become physical, ascribed with the destiny to persist. Commemorating historic moments forces people to never forget. The moment in question becomes static. It inflexibly exists somewhere in the world as a fleshly allusion, enacting our duty to remember. Yet the material, which corporeally shapes the moment, often seems disconnected from what it is incarnating. Anselm Kiefer’s body of work is itself a monument — composed of innumerous paintings, sculptures, installations, and works on paper, formed over a period exceeding 50 years. Every drop of paint, strand of hair, and particle of ash Kiefer uses for his multi-material works are tied to explicit moments. Taken from their former habitual places, Kiefer gives them a new, more permanent home: the canvas.

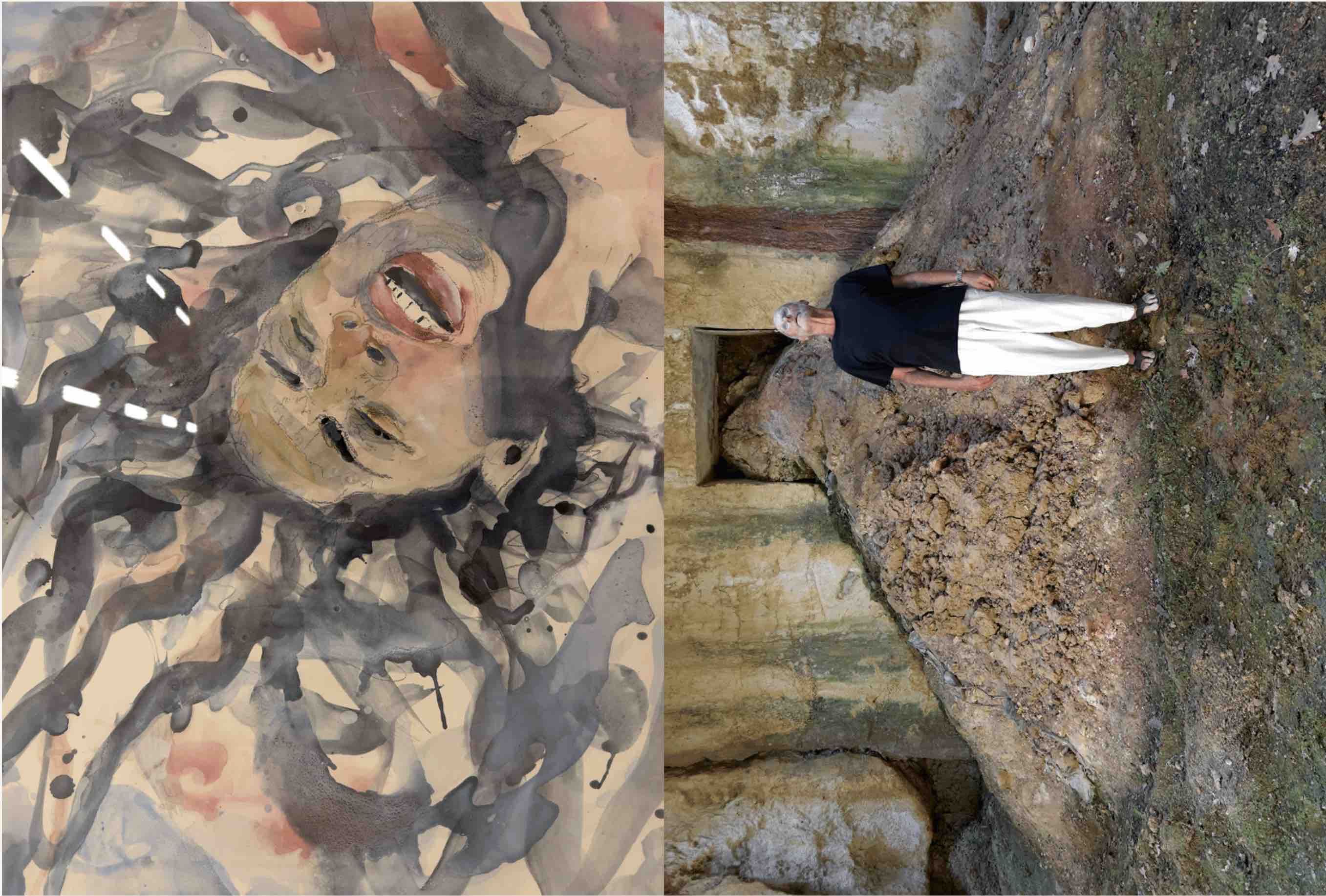

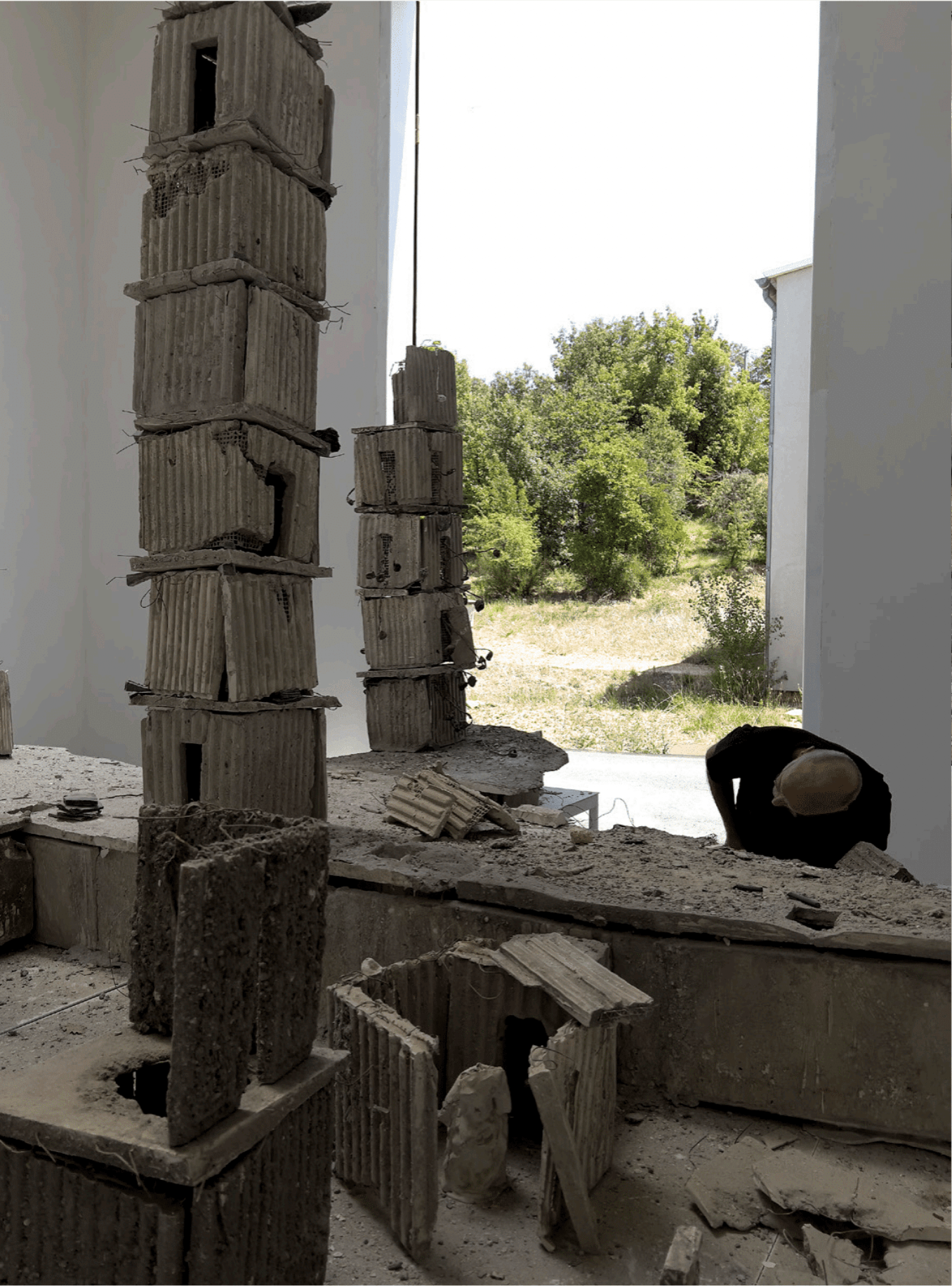

Kiefer’s works are monumental in both size and meaning — even the space where his manufacturing takes place is of tremendous proportions. In 1992, he moved to the small village of Barjac, deep in the heart of le Midi region of France. There, he built a colossal space on a 200-acre property that functions as an atelier, exhibition venue, foundation, and material base for his artworks. The artist’s monumental paintings – or painterly monuments – materialize his vast interest in all matters of life: the Bible, Egyptian mythology, Kabbalah mysticism, German Romanticism, the poems of Paul Celan, and Germany’s fraught history.

Aptly, Kiefer was born in 1945, the start of a new, uncertain era in German history following the devestation of the Second World War. His birth among the rubble of post-war Germany was the genesis for a lifelong fixation with post-war German identity and the national mythology of the Third Reich. His atelier is akin to a laboratory, where his multitude of philosophical, literary, and historical references are tinkered with, tested, and refined. Kiefer pieces together fragments and filaments that constitute a coherent whole. “When I begin a painting, I’m already aware of its destruction,” Kiefer notes. The artist’s works are in a constant state of metamorphosis — a circle of creation and destruction, where destructing is equal to creating. While the term Gesamtkunstwerk might be overused or overenthusiastically applied, this is by no mean the case for Kiefer’s artistic practice. Defined as a membrane of memories, his works are some of the few examples where the term is correctly employed.

SVEN MICHAELSEN: In a 2010 interview with the Süddeutsche Zeitung, the Hollywood star Sylvester Stallone complained that a Kiefer painting he had bought was falling apart: “I spent $1.7 million on it! There was straw on it. Kiefer had glued it on. At home, I startedthinking: shit, what’s under there? Straw. A new stalk every day. I call the guy from the gallery and tell him, ‘the Kiefer’s losing its hair.’ The dealer says, ‘Mr. Stallone, it’s supposed to, the picture’s going through a developmental process, the picture’s alive.’ I thought I was going crazy. 1.7 million dollars! I glued the stalks back on. Every day, I saw another straw lying on the ground and I’d walk over and glue it back on. I just didn’t get it.” What would you have told Stallone to do?

ANSELM KIEFER: That he should glue the straw back on. But to be honest, it’s not all that important. There’s surely enough straw. It’s fine if a little falls off. And I’d say, if he doesn’t want to glue the straw back on, he should send the picture to me. Then I’ll do it. I had an exhibition in the 1980s that passed through four museums in the USA. A conservator was always in tow. At the end, he gave me a big cigar box with all the pieces he had picked up from the [floors]. I thought that was really great.

SM: Stallone sold your picture — something he regrets today: “Oh, I loved that painting, a stunning picture. But, you know, it was really big. It took the whole wallover. And it was really dark. My wife thought the kids might get depressed. Later, Iwished I had kept it for a few more years. German painters have really increased in value since then!”

AK: Jesus, Mary, and Joseph!

SM: Do you know which picture Stallone purchased?

AK: No. But I can ask Waltraud. I’m sure she knows.

SM: Waltraud Forelli, [an Austrian], has been running your studio for 17 years. What sorts of surprises would be disclosed if she wrote a book about you?

AK: I would hope that her book would only be published after my death. I don’t worry about what others think about me or how they view me. But I am always interested in what people see in my paintings. I’m happy when someone discovers something I hadn’t seen. Everyviewer repaints my image in their head.

SM: In Casette d’Ete, Italy, visitors to the production building of Tod’s — the luxury brand run by Diego Della Valle — can see a Formula One Ferrari that had been drivenby Michael Schumacher, as well as one of your large-format paintings. Do you care who buys your work?

AK: I’m not familiar with the man or his company. The only instruction I give to my gallerists is to sell the paintings to people who don’t look at art as investments that can be sold at a higher price later. I don’t want anyone gambling with my paintings. My gallerists aren’t allowed to show my work at art fairs [such as] Art Basel, either. Those halls are lined with paintings for sale that have nothing to do with one another.

SM: Did you know that Stallone bought a Kiefer?

AK: No, important publications about me are sent, but I never learn of such details.

SM: Your compulsion to collect things borders on hoarding. If you eat an artichoke, you dry the leaves and store them away.

AK: I save pretty much everything so I can use them tomorrow or in 10 years in my paintings. I call my storage space an arsenal. When I walk through the arsenal late at night and I’m not totally with it, connections between individual objects are formed. It’s like a synapse transmitting stimuli between nerve and sensory cells.

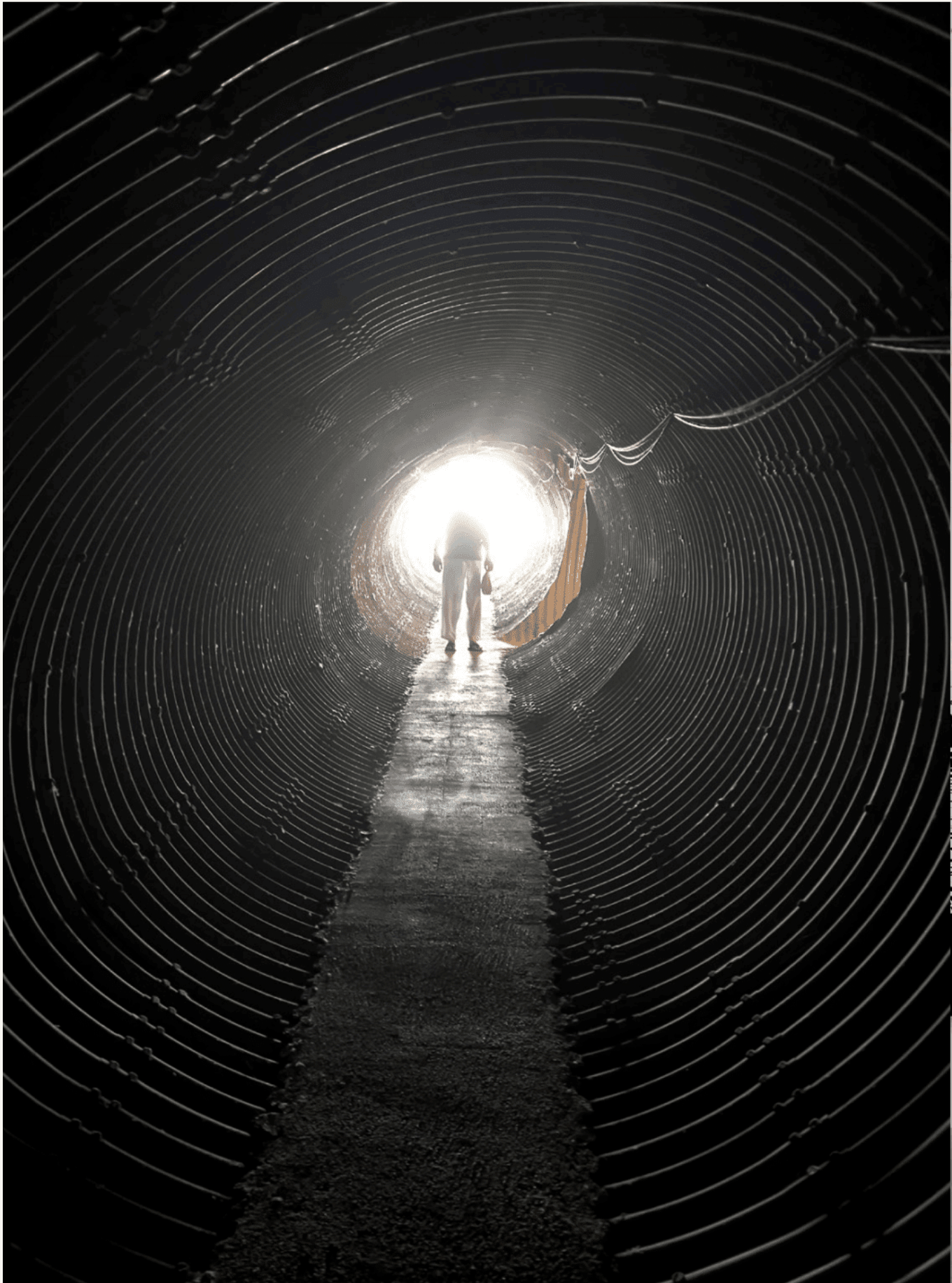

SM: In 1993 you bought a site, the size of 35 soccer fields, in Barjac. Over 14 years, you transformed this site in [southern] France into an artificial landscape with houses, streets, amphitheaters, underground passages, and caverns — one of which was lined with lead and flooded. You’ve only rarely visited the place in recent years. What’s going to become of Barjac?

AK: I turned Barjac into a foundation. Otherwise, the place might be sold after I die. But I want it to be preserved. There are now 50 of my houses with pictures and installations.

SM: You’ve been living and working on a 36,000-square-meter site in Croissy-Beaubourg for some years now. It’s a town, 25 kilometers southeast of Paris, that’s surrounded by highways, and [by] an airfield, where planes take off and land every couple of minutes, making all conversation [at the site] impossible. What drew you tothis inhospitable place?

AK: Nothing suggests mobility like living next to highways and an airport. For the welfare of my soul, I need feel like I can set off at a moment’s notice in any direction. But I still go to Barjac every now and then. When I think that a painting in my Croissy studio might be finished, I have it sent to Barjac.

SM: There have been several robberies in Barjac.

AK: Works of art have been destroyed on three occasions because people were trying to acquire raw materials. The thieves tore my lead books apart and sold the lead. When a work of art is damaged in France, there’s a special police brigade that springs into action. Thatspeaks to the elegance of the French. The special force camped out at the site and ambushed the thieves. After the perpetrators were taken into custody, I was supposed to be a joint plaintiff, but I declined.

SM: Is it true that someone shot at you in Barjac?

AK: Someone shot at the greenhouses. They didn’t aim at me, but they didn’t want me to keep spreading out on the grounds. The message was: “Enough’s enough! Stay where you are!”

SM: You own a house with a studio in the [Marais district of] Paris. Why did you leave it?

AK: It was getting too cramped. Since I rarely finish paintings, they started piling up. I’ve basically always lived in my studios and spend a lot of time alone.

SM: You’re a voracious reader. There are tens of thousands of books in your library,which measures around 60 meters of shelves. The labels on them range from “mysticism” to “astrophysics.”

AK: The first thing I do when I wake up is reach for a book. Right now, I’m reading Pierre Bourdieu’s lectures about Édouard Manet at the Collège de France.

SM: When do you get up?

AK: Sometimes at five, sometimes at eleven. It depends on how long I worked the night before. You could say I’m always working if I’m not sleeping.

SM: You once traveled around the world for three years with your second wife, Renate Graf [an Austrian] — without painting.

AK: I took photos the entire time. It was like painting for me. While taking pictures, I already had the images in my head that I wanted to paint later. So, even taking pictures of the Himalayas or the South Seas was work.

SM: How many hours a day are you busy with managing your world fame?

AK: None at all, actually. I have an office in Paris with several ladies there. They take care of that.

SM: You don’t want to be involved?

AK: I do from time to time. I make sure that catalogues look respectable, for instance. But I don’t work in a network [as] many other artists do. You have to stay away from the business side of things if you don’t want to be distracted from your work — otherwise, you run the risk of taking the market into consideration and conforming to its demands. Such conformism would result in endless repetitions. As I started getting a name in the 80s, I didn’t want my personality to be present at all. When I learned that Newsweek wanted to run a cover story about me, I told the editor, “No, absolutely not!” He couldn’t believe it. I didn’t want my identity to get in the way of my paintings.

SM: You employ nearly 20 people and have thousands of items archived in your arsenal, some of which weigh several tons. Are you ever tempted to throw out your cell phone and run away when it all gets to be too much?

AK: No, because I’m protected from the machinery. Nobody comes into my studio. I’m all on my own there. If someone wants something, they have to call my cell phone. But practicallyno one has the number.

SM: You’ve been asked to say what comes to mind when you hear the word happiness. Your answer was: “I’ve never thought about happiness because it was never important to me. I know many people who ask themselves: Am I happy? Am I leading a happy marriage? Those aren’t real questions.”

AK: I think it’s strange when people ask me if I’m happy. I wouldn’t even know whatsomeone means when they say they’re happy. The word happiness doesn’t exist for me —I’ve got things that need to be done. I’ve got a job, I want to make something, accomplish something. The question of whether I’m happy isn’t something that occurs to me. If it did, then I would already know that something was wrong with my pictures.

SM: In portraits about you, it’s been said that you have ecstatic feelings of redemptionwhile painting.

AK: Sometimes, but very rarely, there’s an illusory state that might be what redemption feels like. It’s like having a visitation that overwhelms you. But these are occurrences and not states.

SM: Your first experience of art is said to have been a Wagner opera on your mother’s cheap radio.

AK: I wasn’t even 10. It was a broadcast of Lohengrin from the Bayreuther Festspiele. I grew up on that opera. Around that time, I read Tolstoy’s War and Peace in bed at night. Rilke and Stefan George entered my life at the age of 15. Then, at 17, I followed in the footsteps of van Gogh through Holland, Belgium, and France.

SM: You considered becoming a writer for a long time.

AK: That was a struggle. When I turned 17, excerpts from my diary were published and highly praised by an influential critic. But you can’t do both writing and painting.

SM: You’ve kept a diary to this day. Do you grumble about the crises in your life, your two divorces, and five children in there?

AK: No, I think about my pictures and talk to them in my diaries. Or I have discussions with myself about what my next exhibition should look like.

SM: How many volumes are in your diary?

AK: Sixty-eight. I’m of a certain age, after all.

SM: You’re 77. Will you publish a best-of from your diaries during your lifetime?

AK: I don’t think so. It’d be too much work to look through 68 volumes. It might be possible if I find a good editor someday. But I’m still young. I still have some time left.

SM: Your father died four weeks before his 100th birthday. If you lived as long as him, you’d have until 2045.

AK: Yes, I hope to make it to 100 years, too.

SM: You recently published an excerpt from your diaries. There, you describe Croissy as your “exile” and admit that you never felt “at home” in Barjac, and that it felt like you were always “passing through.”

AK: I left Germany in 1991. Sometimes I think it was a mistake, but a mistake is never negative for me. Something always comes out of it. Something good can come, even in the wrong place.

SM: You were born in a hospital’s air-raid shelter in Donaueschingen two months before the Wehrmacht capitulated. The ruins and rubble from the war later became asignature of your paintings.

AK: Donaueschingen used to be a railroad hub and was bombed. My parents say they put wax in my ears so I wouldn’t hear the alarm sirens and bombs exploding. The only thing I played with as a child was rubble and debris. I built houses and dams out of charred beams and splintered bricks. I’m still doing something similar today. An artist always only ever works with what he experienced during his childhood and youth while he was still unable to process everything and make judgments. The same goes for writers: The only [materials] they have are the secrets from their childhood. I would find parallels to my childhood in a lost world,even if I were on Mars.

SM: Why are ruins “the most beautiful thing in the world” for you?

AK: Ruins are ideas and building materials from which something new can emerge. Life is concealed in them, since we aren’t able to know what will result.

SM: The two world wars of the previous century are present in many of your paintings. Did the Russian invasion of Ukraine surprise you?

AK: The wars of the world will never stop. War is a historical constant because a flaw crept into the construction of humans that seemingly cannot be corrected. Nevertheless, demandinga world without war isn’t meaningless. Each of us has to desire the impossible, even if it doesn’t seem attainable. But we need to think further: if part of the world will be under water because of the climate crisis, then one of the main conflicts is going to be migration. The unfortunate debate about identity pales in comparison to such problems for humanity.

SM: Suppose a video camera were installed in your studio. What would viewers learn about your way of working?

AK: When I begin a painting, I’m already aware of its destruction. It has to be destroyed by me again and again and remain provisional. It’s an arduous battle, an internal struggle, since every discarded possibility is a loss. For me, true artists are iconoclasts. A painting attacks itself like a body suffering from an autoimmune disease. That’s why I don’t believe in magnus opuses or masterpieces — they don’t exist, for me at least. The completed masterpiece is unattainable since, for me, a painting is never finished.

SM: With age, have your self-doubts decreased or increased while [you work]?

AK: The basic problem remains the same: it’s painful to never achieve what you aim for. The difference between the 70s and now is that I no longer suffer from total despair. I know that constant doubt is part of it, and I know that I will keep going.

SM: Are you ever plagued by blocks, [as are] writers who suddenly don’t know where to go from one sentence to the next?

AK: I’ve known the Nobel Prize for Literature Laureate Peter Handke for many years. I always tell him that he has the advantage of being able to work from wherever he wants. All he needs is a pencil and paper. But I can’t do that. The advantage I have, though, is that I don’t have any blocks, since I work with matter. There’s always something that can be done.

SM: You treat your pictures with a pickax, ax, flamethrowers, and [you] melt down tons of iron to make warships and airplanes that are several meters high.

AK: In the studio, I’m like a child happily absorbed in the game he’s playing. If you lose that playfulness, you might as well give up. Sometimes, there are works where you can’t see its ending. Then you have to be disciplined and just keep going. The moments when you despair because you can’t see the finished product but keep working regardless are often the most productive. For me, playing and discipline and intention always go together.

SM: Are there moments of inspiration for your pictures?

AK: I only paint when I experience a shock that I feel like I need to address.

SM: What triggers such a shock?

AK: A poem, a piece of music, a landscape, a flash of light, a passage from the Bible, an artwork, a historical event that I’ve read about and find some parallels with today. That’s when it gets going. I make something because I’m overwhelmed. The interesting thing is that shocks are memories not only in the head but also deep in the cells.

SM: When your colleague Jörg Immendorf was found by the police with nine prostitutes and about 20 grams of cocaine in a hotel in Dusseldorf, he said painters need a degree of orientalism as a stimulant.

AK: A nice phrase that I would never say. I don’t get high from cocaine or orientalism, even when I don’t have anything against them necessarily. I become intoxicated when I experience the shocks I was just talking about. There’s a throbbing that drives me to action.

SM: Your paintings must number in the thousands. Do you ever come across one that you painted 40 or 50 years ago that you forgot about?

AK: No, I can immediately tell whether it’s a painting from me or not. I can also immediately tell when it’s a fake. All I need is a photo.

SM: Gerhard Richter turned 90 in February. Is it true that the two most famous German painters have never met?

AK: No, no, I’ve met him.

SM: When?

AK: It was in 1971, I think. I was almost finished with my studies, and I visited him. Then we met by coincidence at the Venice Biennale in 1997. No conversation resulted from [the two]meetings. Richter is very busy with his own world and works in total seclusion. I also want to be left alone.

SM: A journalist once asked you why Richter’s paintings are more expensive than yours. Your reply was that your works don’t fit in a safe because of their size, which lowers their price.

AK: Well, that was just a humorous answer, but it’s true that my pictures don’t serve as decoration and don’t fit in a safe. They also can’t be shown in a salon or on a yacht. Maybe that’s why they’re so big.

SM: The wealthy like to say that wealth isn’t interesting to them. You go one step further and claim to be interested in the destruction of capital.

AK: Any money that comes in is put straight back into the work. That’s why I don’t have any wealth in the classical sense. My houses in France and Austria are places of work, they’re tools. The train de vie of rich people was never anything for me.

SM: You charter helicopters for larger distances.

AK: There’s a reason for that. When I need to go to Barjac from Croissy, I can’t sit in the car for six or seven hours until I finally arrive.

SM: Do you sell everything you paint?

AK: No, most of it ends up in the foundation. I [sell only] as much as I need to keep working.

SM: Visitors to the Panthéon, the French national hall of fame where greats [including]Rousseau and Voltaire are buried, walk by six of your works that are permanently installed on stone plinths in the chancel and naves. Has your ego ever blown a fuse?

AK: There’s also a large painting of mine in the Louvre. But it has nothing to do with megalomania. I’m possessed by less and less of that. I didn’t aspire to hang a work in the Louvre. I was asked. The same is true of the Panthéon. I never saw it as a simple goal that I needed to find a solution to.

SM: The commission for the Panthéon came from France’s head of state Emmanuel Macron. You are the first artist to have created works for the hall of fame since 1924. In such moments, do you ever think: now I could die?

AK: On the contrary. Instead, I realize that I’m far from where I want to go. Psychologically speaking, so-called achievements are the surest way to stagnation and routine. Whenever I read a poem by Celan, I feel very small and humble and want to hide because I think that I’ll never achieve something like that. I have the same sense of reverence when I devote myself to Goethe’s Faust II.

SM: You’ve repeatedly engaged with the life and work of Celan in your paintings. Whendid you first come across him?

AK: Celan’s Todesfuge [Death Fugue] was examined in the higher school grades. This poem fascinated me immensely. It was a hammer blow whose reverberations became louder and louder. In the 80s, I painted Dein blondes Haar, Margarete, an entire series that was inspired by the Todesfuge. Celan’s language had nothing in common with ordinary language. It’s like that of an alien who comes from a world none of us has ever visited. You understand a fragment here and there, but nothing more. I think he’s the most notable figure of the 20thcentury. He was born in what is now the Ukraine. He spoke seven languages but only wrote poems in German. And it was the Germans who killed his parents and locked him up in a labor camp.

SM: In your experience, does the name Paul Celan still mean anything to people today?

AK: The discrepancy between his importance and fame is immense. For me, his poems are the only thing that’s real. The rest is but an illusion. It’s obvious to me that the majority of people don’t see it [this way]. There are only a few who want [to], or are able to, project themselves into his works.

SM: In 1965, you started studying law and romance philology in Freiburg. It’s hard to put you and law together.

AK: I never thought of actually becoming a lawyer, but I was so impressed by the clear thinking of the jurisprudence that I thought: that’s what I want to study. I was actually a pretty good law student.

SM: Why didn’t you study art from the beginning?

AK: I didn’t want to go to an art academy because I was deeply convinced that I was the greatest living painter — without having any reason for it, of course. Back then, I was a megalomaniac. At the age of five, I wanted to be the Pope, but people told me that only Italians become popes.

SM: Do you have any notion of how this genius complex came to you?

AK: It never came to me. It was always there. There were no motives or reasons coming fromthe outside.

SM: Does greatness exist without delusions of grandeur?

AK: Yes, Anton Bruckner was always like a mouse confronted with a snake when he met his contemporary Johann Strauss, whom he considered to be greater. But he still composed wonderful music.

SM: You were raised in a strict Catholic family and were an altar boy. Your father became a Wehrmacht soldier at 18 and fought in France and Russia. After the war, he was an assistant teacher.

AK: He was a captain or major or something. He later told me that this was why he was never allowed to study. Whether that’s true, I don’t know. The Wehrmacht was something sacrosanct at home. War crimes were never discussed. Fascism was dealt with in 10 days at school. Alexander the Great was talked about for much, much longer.

SM: You told the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgård that “I wished my father would die.”

AK: He was authoritarian. There were threats and beatings. It was pretty bad at home, I’d say. My mother gave me to my grandmother for the first six years.

SM: Why?

AK: You can find reasons for it if you want to. There were multiple families quartered in the house that she lived in. She was happy to only have to deal with my sister.

SM: After prematurely stopping your studies of law and Romance philology, you studied fine art — with Joseph Beuys amongst others. In 1969 you submitted a series of photos [titled Besetzungen <Occupations>] as your exam thesis, a series which triggered one of the biggest art scandals of the time. The black-and-white photos depict you making a Hitler salute while wearing your father’s Wehrmacht uniform in Italy, France, and Holland. How close and how distant is this 24-year-old action artist to you today?

AK: Very close. I was never looking for political provocation but wanted to learn something about myself. None of us can say what we would have done during the Nazi era. But you can try to imagine what your stance would have been. At the time, National Socialism was a dark stain that no one wanted to talk about. I sensed that there was something unpleasant that was being whitewashed. I wanted to explore this repression.

SM: A second motive for your Besetzung series is said to have been something you experienced as a child.

AK: When I was six, I killed chickens with a spade. Although the killing was legitimate since they were eating the salad in our garden, I can still see the white chickens lying dead in their blood on the damp, dark earth. That was a shock. I was horrified and disgusted with myself. If you slay chickens at a young age, you wonder what sort of abysmal evil resides in human beings. Where is the flaw in the design?

SM: You were an ostracized figure among German art critics until the mid-80s. You were accused of being a mythomaniac obsessed with giant formats whose art exhibited an alarming “overdose of Germanism,” as one critic put it. This rejection [changed only]after you saw success in the USA and Israel.

AK: German art criticism is hair-raising anyway. Just two examples: in 1992, when I exhibited the paintings that made me a star in the USA [at] the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, there wasn’t a single good review, not one. That’s really remarkable. When I received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in 2008, someone wrote that it’s like awarding Uli Geller the Nobel Prize for physics. The Germans are really peculiar.

SM: Increasingly, critics are expecting artists to desire to change the world, which they either agree with or reject. What’s your assessment of this development?

AK: Artists aren’t activists or influencers, and art is not an elitist form of social engagement. This moral cudgel is idiotic. We’d have to do away with half of art history. I feel like I’m a political painter because I engage with European history in my work. But I’d be devastated to paint the political realities of the day. My art isn’t an Instagram post.

SM: Many no longer hold the opinion that an artist’s work and morals should be considered separately.

AK: That’s totally absurd, since art has nothing to do with morality or social commentary. Every form of morality is dependent on its age and the society it surfaces in. All of us look up to the Greeks because they established democracy. Yet, they thought it was totally normal to have slaves. Are we in favor of slavery? No. Were Socrates and Aristotle great thinkers? Yes. What’s called “cancel culture” today is really the resurgence of the witch burnings from the Middle Ages. If artists, poets, and writers were judged according to their moral standpoints, then we’d have to destroy the works of Céline, Jean Genet, Ezra Pound, and de Sade, for instance. We’d also have to ban Joseph Beuys. In 1972, he wanted to give a tour of documenta to the despised RAF terrorists Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof.

Credits

- Text: SVEN MICHAELSEN

Related Content

032c Issue #42 “DRAIN GANG” Winter 2022/2023

Artist YNGVE HOLEN Could Be Our Travel Agent

Collecting – and Celebrating – With Publisher BENEDIKT TASCHEN

The Book of Gucci According to Alessandro Michele

LIL UZI VERT Isn’t a Satanist

In a Perpetual Now: ROSA BARBA at the Neue Nationalgalerie

Disco Isn’t Dead. It Has Gone to War

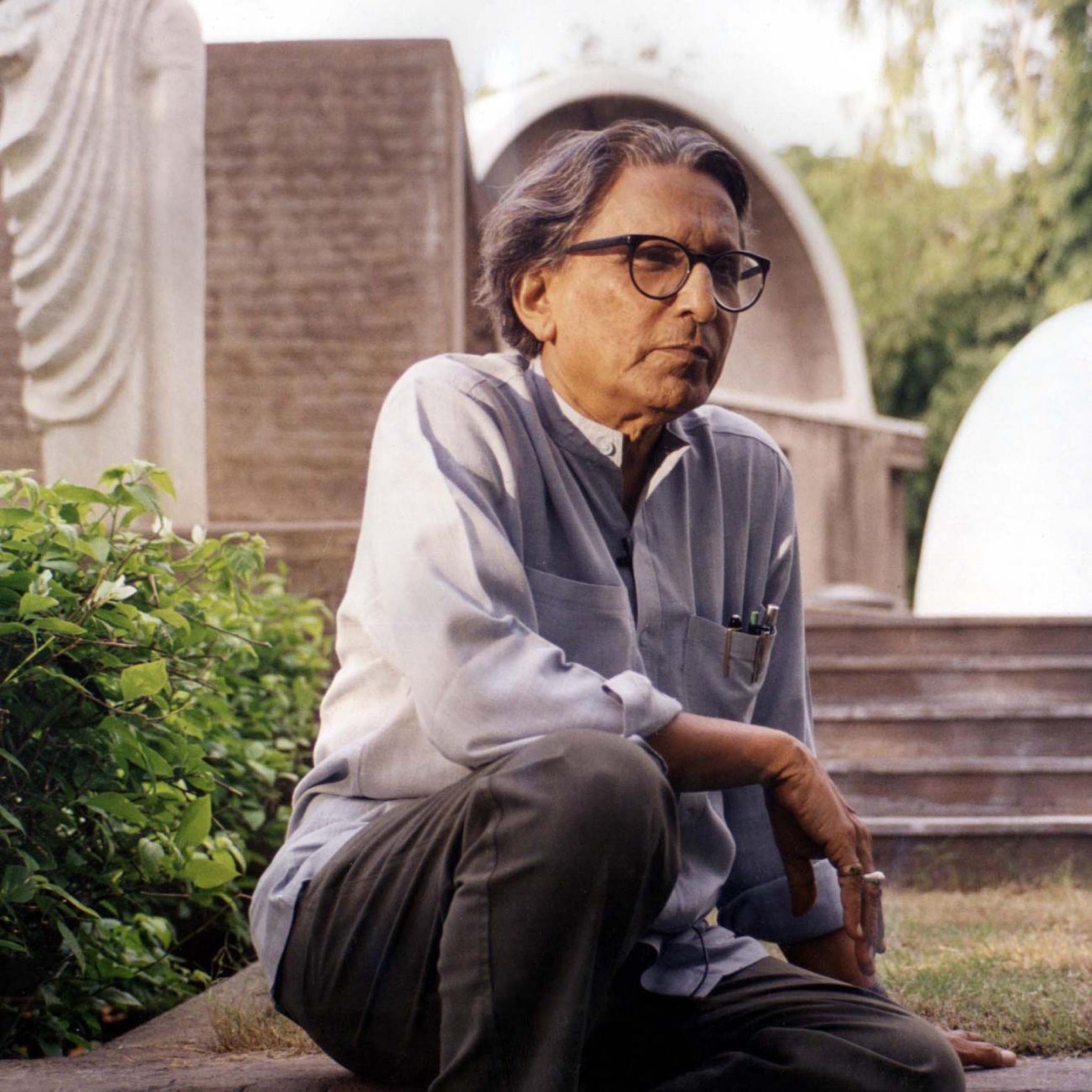

Rest In Paradise: BALKRISHNA DOSHI (1927-2023)