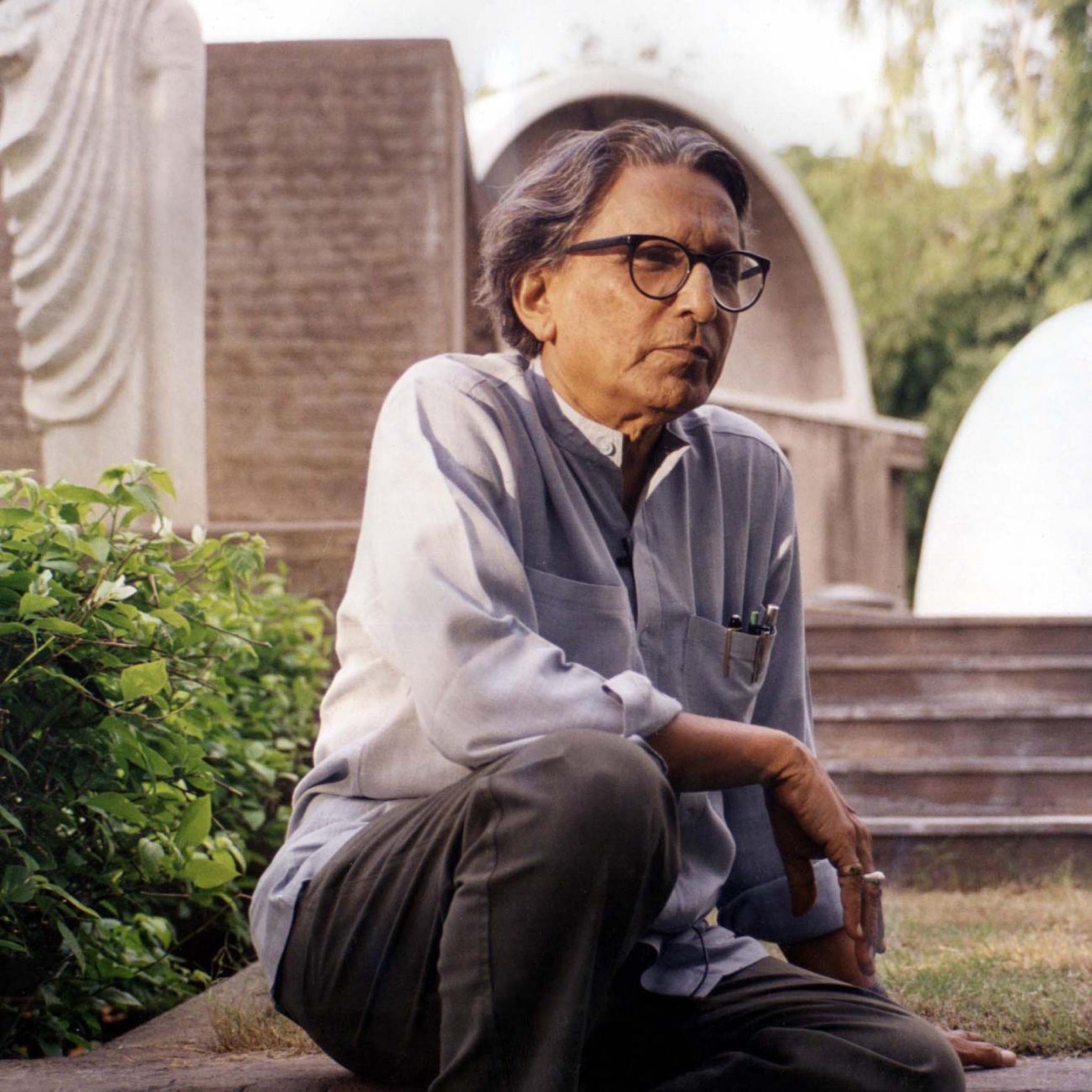

Rest In Paradise: BALKRISHNA DOSHI (1927-2023)

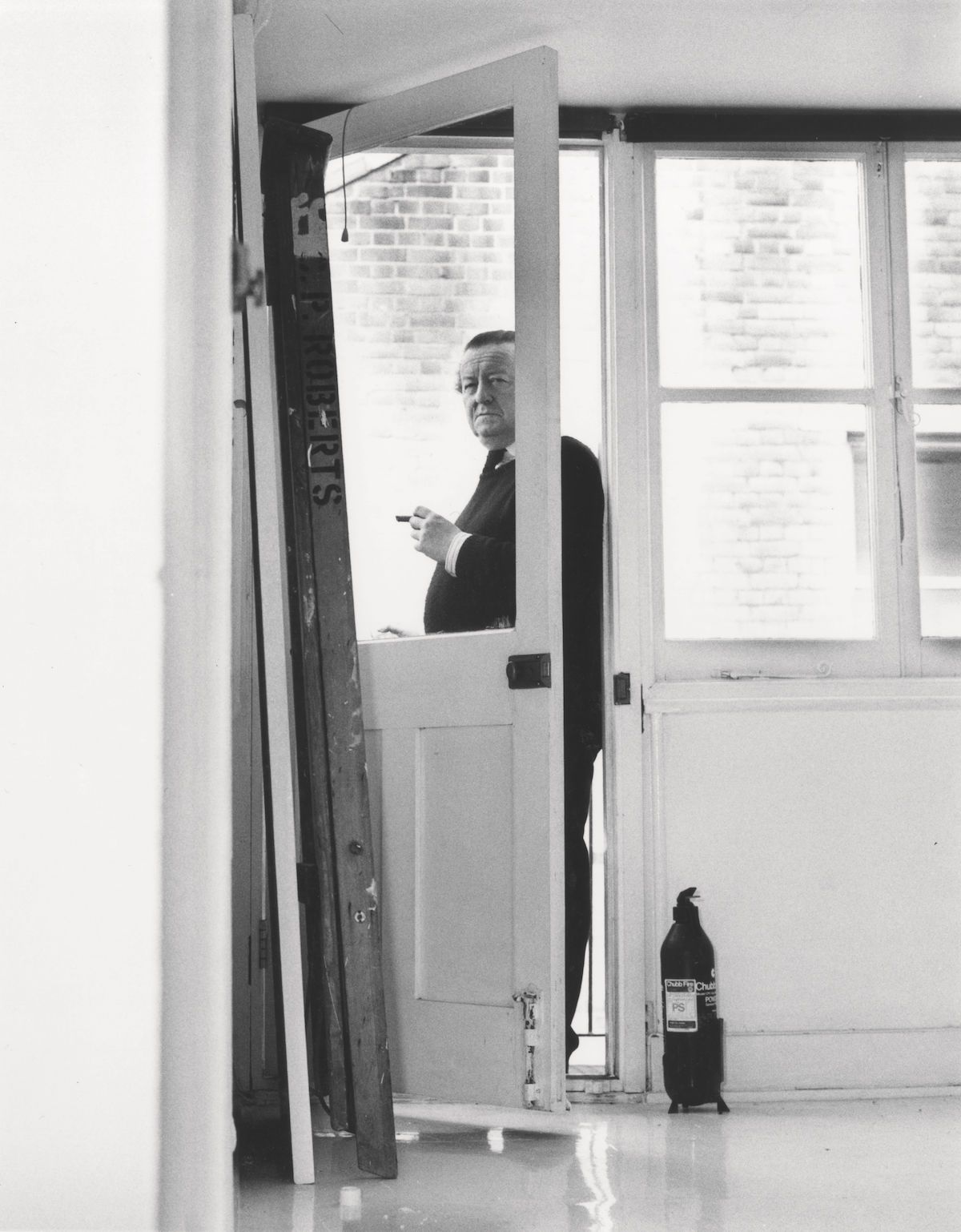

|Sven Michaelsen

Balkrishna Doshi (1927-2023) sits at the top of the Pantheon of Indian architects. A student of Le Corbusier, Doshi’s works straddle tradition and modernity, using classic Indian architectural motifs alongside those of modernist and brutalist traditions. The breadth of his projects is vast, from private homes and government buildings to entire cities — but he is especially noted for designing university buildings at campuses across the country. Interviewed by Sven Michaelsen in 2020, read our interview with the man who, quite literally, helped build modern India.

BALKRISHNA DOSHI DESIGNS BUILDINGS, BUT HE DOESN’T BELIEVE IN OWNING THEM. MEET THE 91-YEAR-OLD PRITZKER PRIZE-WINNING ARCHITECT WHO HELPED LE CORBUSIER BUILD CHANDIGARH AND BROUGHT BRUTALISM TO INDIA.

Last year, you were awarded the Pritzker Prize, the world’s most prestigious award for architects. You said in your acceptance speech that you followed your intuition when you stopped studying painting after two years and opted for architecture. Do you often have such intuitions?

Each of us has an inner clock and an inner voice. I’ve been working to hone my sense for these signals for 60 years because they’re the most valuable thing we have as humans. My father owned a furniture shop, which he had taken over from his father, and everyone expected me to follow in his footsteps. That felt like the wrong thing to do, so I turned to painting. But that didn’t suit me either. When I moved away from my hometown, Pune, to study architecture in Mumbai, I knew next to nothing about architecture, but something told me I could find my destiny in it. I lived in a one-room boarding house with five beds in it. Someone different slept next to me every night. It was like a train with people constantly getting on and off. There was only one other permanent lodger. We became friends. When he received a job in London after three years, he asked if I wanted to come along – I could just as easily continue my studies in England.

Did you speak English?

Only very, very badly. But I still had the impulse to follow him, and so in 1950 I landed in London after a two-week sea voyage. A couple of weeks later, I heard about a congress with famous architects from all over the world. I went to the nearest payphone and called to ask if I could participate. They said it was impossible, I didn’t have a diploma. But I was allowed to be an audience member, after earnest pleading. When I entered the hall, a man approached me and introduced himself as Germán Samper. He wanted to know whether I was Indian. When I confirmed that I was, he told me that he was planning something with the architect Le Corbusier in India, in the new city Chandigarh, and he asked me whether I could tell him what the name means. After I explained to him that the name referred to the goddess Chandi, I asked for a job with Le Corbusier, saying it would be helpful to have an employee who knows the country and its people. Samper replied that I’d need to apply with a handwritten letter because Le Corbusier believed in the importance of graphological expertise. That evening, I wrote an application in English and had an acquaintance correct it. It was only after the sixth try that it was flawless.

Along with Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, born in Switzerland in 1887 with the name Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, was one of the most famous living architects at the time. What made you hope that the 64 year old could be interested in a 24-year-old nobody?

I knew who Oscar Niemeyer was at the time, but the name Le Corbusier meant nothing to me. That’s why I wasn’t awestruck. It was the connection to India that attracted me. I followed this impulse in my letter. The answer I received was unfortunately in French. I went to the Royal Institute of British Architects and had the letter translated by a librarian who was a Francophile. I was told that I could do an internship in Le Corbusier’s Parisian studio for eight months, but without pay. I had little money, so I asked my classmates what I should do. They couldn’t believe that the name Le Corbusier meant nothing to me. They considered the internship the opportunity of a lifetime.

A couple of days later you made your way to Paris.

On the Channel ferry, I was sitting next to a trustworthy-looking man with a tweed jacket and glasses. I showed him Le Corbusier’s letter and asked whether the given Parisian address meant anything to him. He replied that it did, because he was acquainted with the gentleman in question. Then he wanted to know why I looked so depressed. I told him that I had very little money and didn’t speak a word of French. He then offered to share his hotel room in Paris with me. And he paid the bill when we ate an omelet in the evening. He also brought me in a taxi to Rue de Sèvres. “Do you see number 35? That’s where Le Corbusier works.” I got out and wanted to pay the driver, but the taxi drove away. My benefactor probably wanted to spare me from thanking him. You don’t have to call this chain of circumstances magic, but I felt like I was being guided by a higher power and that I would be starting a new chapter in my life. And so, just like I did in India, I put my bag on my head, crossed the street, and rang the bell at number 35.

What kind of environment was awaiting you?

When I showed Le Corbusier’s letter to the secretary, she shook her head and came back with a man I recognized as Germán Samper. “Mr. Doshi,” he said, “you never wrote us to say whether you intended to do your internship with us.” He was right – the thought never occurred to me. Later he would tell me that he went into Le Corbusier’s office and said that a gentleman from India was standing at the front desk with his luggage and planned to stay for eight months. Le Corbusier is said to have growled out: “The man made the journey to Paris from India? By the name of God, he can stay.” That’s how my real life began.

How did you survive in Paris?

My savings were enough for a diet of baguette, olives, and cheese. Two months before the end of my internship, I was told that I could stay and would start receiving a salary.

Did you make friends?

Not at first. I felt like the loneliest person in the world after everyone left the office at 6pm. Since I’m a strict vegetarian and didn’t have any money, I never went to lunch with the others. And if I wanted to eat a cheese sandwich, I’d have to point with my finger because of the language barrier. I sat alone in my hotel room in the evening, drinking milk and crying. To overcome my anguish, I kept repeating a sentence from the coat of arms of my school in Pune: “Always finish every task you have begun.”

What did Le Corbusier’s executive office look like?

Tiny. It was only 226 by 226 centimeters. Everything was black. I don’t think his best ideas occurred to him there. Once I watched him on the street while he waited at a traffic light in his car during Parisian rush hour. He remained there when the light turned green. People were screaming and wanted to call the police, but Le Corbusier sat calmly and wrote something in his notebook. When he was finished, he screamed something back. When I later asked him about the incident, he said that there are moments when a blessing descends on you and these moments have to be taken.

You began as Le Corbusier’s exemplary student and then became one of his most important collaborators for projects in India for four years. What did your mentor see in you?

He never told me. He would come to my desk every day in the first few weeks and say, “Bonjour, bonjour.” Then we would swap seats and he would give extensive comments on my designs or would take a piece of paper and a colored pencil, and draw what he thought could be done better. Since he didn’t like speaking English, and I couldn’t speak a word of French, we communicated with hands and feet. I learned the ABCs of his architectural philosophy nonverbally.

One of your first tasks was a detailed design for buildings in Chandigarh, a planned city of 500,000 inhabitants in the northern Indian state of Punjab. Why did Le Corbusier receive this prestigious project and not an Indian?

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Indian prime minister after the end of British colonial rule, wanted to use Western modern state architecture to smack the country on the side of the head so that it would wake up to its future. Chandigarh was supposed to become a symbol of departure and of technical progress.

“Sustainability is an Indian invention. Poverty never wastes anything.”

Le Corbusier was considered withdrawn and unapproachable. But he often tenderly called you “mon petit Doshi.” What was he like as a person?

There was something of a hermit and mystic about him. He never wanted to see anyone until noon. The mornings were reserved for art and contemplation. He once spent four days in isolation without enough food – he wanted to see whether his fame tempted him to be self-righteous and to simply repeat himself. By the end, he was more convinced than ever to do the right things with his buildings, down to the smallest details. A client once complained that the 70-centimeter toilet doors were too narrow. Le Corbusier replied that a pregnant woman with two suitcases could easily walk down a train aisle and that the gentleman wasn’t much wider than that.

Le Corbusier biographies claim that India radically changed his aesthetics. Is that true?

The first time we had a meeting in Chandigarh, he said that we needed to think about making a pact with nature. It would be an ethical mistake if he had buildings fabricated in India according to the maxims of European modernism. He had always understood architecture to be the antithesis to nature, but then he became concerned with the connection between the two. The world in North India was unfamiliar and overwhelming: merciless sun, temperatures between 9 and 49 degrees Celsius, weeklong monsoons, temples, cows and elephants on the streets instead of cars, the silhouette of the Himalayas. He wanted to react to this kaleidoscope of impressions with a local architecture.

Normally architects are given strict guidelines as to what they should build and at what price. Why was Le Corbusier given free rein in India?

The briefing delivered to Le Corbusier was that he was a world-famous architect and that he should design something revolutionary, a vision for the 21st century. It wasn’t any more precise than that, because trust is an inherent principle in Indian culture. If I buy jewelry from a street vendor, I can be sure that his prices are fair.

Le Corbusier wanted to level half of Paris’ historic center in 1925 to build sixty-story skyscrapers. Should we learn to fear architects with a revolutionary impetus?

No matter how beautiful it may be, if you want to build a utopia, you make yourself an enemy of everything already in existence. Le Corbusier was in his late 30s when he developed the plan for Paris. I suspect he saw things differently later in life.

If you could sum up your experience with Le Corbusier in a single sentence, what would it be?

During an exchange of ideas he once said, “Every morning, I’m born in the body of a donkey.” What he meant by this is that you can never simply believe that you’re somebody – you need to work every day to become someone. Whoever wakes up as a fool in the morning has the freedom to go his own way with the spontaneity and curiosity of a child. Nevertheless, our profession entails a particular responsibility – of all the arts, architecture has the greatest impact on the life of a society. If a painter’s picture turns out badly, it doesn’t matter. But what if an architect designs houses that bring out the worst in people?

In 1962, after six years of working with Le Corbusier, you started a 14-year working relationship with the American Louis Kahn, another pillar of modernist architecture. Who did you learn from more?

Le Corbusier was my guru, Kahn my yogi. Both helped me to discover the true teacher: nature.

Were there similarities between Kahn and Le Corbusier?

Their characters were completely different. Kahn was more of a prudent person, focused on analysis and perfection. He only ate boiled fish and boiled potatoes when he was in India. Le Corbusier was reckless and searched for the unknown. He loved crises because they required unpredictable solutions. For him, architecture was an artistic game of discovery. He once said, in allusion to his paintings: “My picture is blue in the beginning. When I finish, it’s green. I’m not sure how it happened.” Kahn’s buildings were an invitation to meditate, Le Corbusier’s an invitation to sing.

In 1956, you founded your architecture studio, Vastu Shilpa, in Ahmedabad. To date you’ve designed around 100 buildings, from private homes and government buildings to universities and entire cities. Is there a guiding principle?

I am concerned, even to this day, with the synthesis of modernism and the local traditions of India. How can the ideas of the European and American avant-garde merge with the things that make up my home: sun and rain, the drama of light and shadow, the ubiquity of religion and mythology, harmony with nature, sustainability? Sustainability is an Indian invention. Poverty never wastes anything.

You designed the satellite city of Vidhyadhar Nagar, outside Jaipur, in the mid-1980s: social housing for 400,000 people that was energy efficient. Then, in the late 80s, you were responsible for planning 6,500 social housing apartments for 80,000 people at the Aranya Housing Project in Indore. Famous architects like talking about designing apartments for the underprivileged, but rarely do it. What drives you?

My life would feel incomplete if I didn’t also care about housing and urban planning for the poor. Good architecture may not solve social problems, but it can prevent them from getting worse. A housing estate can demonstrate the desire to create boundaries, or it can be a catalyst for harmony, togetherness, cooperation, tolerance, modesty, and forgiveness. Aranya Housing Project was meant to be a place for people who belong to different castes and religions, and who have different incomes. In order to create a sense of neighborhood and togetherness, we paid attention to the public spaces, markets, arcades, green spaces, and verandas. It is more important to create communities than to build edifices.

But aren’t planned communities that are plucked straight off the drawing board horrible for their inhabitants?

People feel like animals in a zoo at first. But architecture isn’t static; it’s a living organism. Time has to pass before a manmade city is worth living in. We designed the houses such that they could be changed by the residents according to their needs. When the children are born, you can build another floor. When the parents get old, you can add a veranda for them. With this modular system, the residents create their own cityscape, and people become their own architects over the years. I spent my childhood in my grandfather’s house, an amorphous structure that was adapted every couple of months to changing needs. I’ve rarely experienced as much happiness as I did in this work in progress, where at least 15 people sat around the dining table. The first thing you learn in a big family is to share, to be patiently tolerant. You understand that everyone ticks differently but that no one has more worth than anyone else. Maybe it is the desire to make a big family happy in a building that has shaped my work more than anything.

Would you like to live in a planned city?

Old people like planned cities because they can easily find their way around in their logical structure. Young people tend to like cities with tradition because life pulsates in them. But to experience that, they have to put up with complexity, dense traffic, and high rents.

You’ve never accepted contracts outside of India. Were you ever tempted to build glamorous skyscrapers or concert halls in London or New York that would give you the aura of a celebrity architect?

No. The pyramids in Egypt were built by potentates who were concerned with their fame. Buildings served as a vehicle for immortality. It seems to me that many buildings from our time are supposed to serve the same purpose. To call myself an architect of the poor does not do justice to my buildings, but I would never think of using expensive materials like marble. Status is very important in Indian society and that’s why it’s so intent on making differences. An architect has the choice to support this partition, or to break down hierarchies.

“Le Corbusier was my guru, [Louis] Kahn my yogi. Both helped me to discover the true teacher: nature.”

When you were born in 1927, India’s population was 270 million, today it’s 1.3 billion. Every year 15 million more people are born. Do these numbers elicit apocalyptic feelings for you?

No, the future of my country lies in the mentality of ordinary people. They’re not fatalists who sit on their hands; they believe in compassion, sharing, and togetherness. India is not overpopulated. My country has enough resources to feed its inhabitants – they just finally need to be distributed more equally!

If you could only save one of your buildings from being demolished, which one would it be?

The Indian Institute for Management in Bangalore, completed in 1992, unites almost everything I’ve learned about the symbiosis of modernism and Hindu traditions. But I couldn’t live in it – there are no beds in universities. That’s why my choice would be the building we’re having this conversation in.

Sangath. It’s in Ahmedabad and combines your architectural office, an idea lab, and an event space.

I planned Sangath between 1979 and 1981 with very little money. There were no precedents for the design in India, Europe, or America. It’s my most autobiographical building – or, if you like, my manifesto. Sangath means “moving together” in my native language, Gujarati. I wanted to create a building that’s an invitation to community spirit and cooperation, and that also expresses harmony with nature. The building is sunken halfway in the ground, so air conditioning isn’t necessary.

Compared to the offices of famous architects in Europe or the US, Sangath makes a very modest impression.

The focus of architecture should be on life and not on itself. Where we put our focus shows whether we are open or self-centered, spiritual or materialistic, sensitive or brutal.

You are 91 years old. What does your day look like?

I get up at 5:30am, do my physical exercises, and go for half an hour to a small temple that’s part of the house. Afterward, I spend time with my family. I go to the office somewhere between 10 and 11. Awaiting me are to-do lists I’ve ignored for 30 years. More important are reading, reflecting, developing questions, and listening to music.

Anything in particular?

Ravi Shankar, Bhimsen Joshi, Kumar Gandharva, Kesarbai Kerkar, Sharafat Hussain, Igor Stravinsky, Bach, Vivaldi, Iannis Xenakis. One of my favorite albums is Keith Jarrett’s The Köln Concert.

Are you spiritual or religious?

I’m a Hindu who believes in the unknown. On one hand, our destiny is preordained. On the other, our actions are decisive for our karma, which is decisive for our reincarnation. Our relationships to other people don’t end with our death; they take on a new form. This leads to humility and to accepting the blows of fate. My wife belongs to Jainism. For them, every physical entity has a soul – not only people and animals, but also plants and water.

People who say they know you often claim that the most important figure in your life was your mother. Would you agree?

My mother died when I was ten months old. I only know her from photos. Nevertheless, I often think that she’s the strongest force in my life. I hear her voice whenever I feel lonely and desperate. When I was 11, I had to stay in bed for six months from severe burns and the doctors were ready to amputate my right leg. I never would have survived without the healing touch of my mother. She gave me courage and assured me that everything would be fine. She’s also present in this interview. She’s in my pocket, listening to us.

Have you had any other similar experiences?

Yes, when I was eight, one of my aunts often fell down and needed to be cared for. When I came home after school once, she was lying on the ground with her eyes closed. In a trance she said, “Come, sit with me.” Then she told me what I had experienced at school that day. It was a ghost speaking from her – and it was right about everything. Sometimes it also spoke with my mother’s voice.

You don’t own your private home or Sangath. Why?

I don’t want to own anything. It’s been like that for a while. My treasures are my dreams, my thoughts, my ideas. Possessions aren’t important, because we’re mortal. Don’t look at the things a person owns, but at the motives they were acquired with. When you do this, you stop being jealous of the possessions of others.

“The focus of architecture should be on life and not on itself.”

How long have you thought this way?

When I was 15, my father married a woman neither my brother nor I could stand. In protest to our stepmother, we moved into a room under the roof and looked after ourselves. We rented a place nearby a couple of months later. We were almost penniless. Our clothes were made from the sheets our aunts gave to us. I took the vow of not owning possessions at that time. It made me happy to want nothing of material value. Having minimal needs makes one courageous and free. I never had to accept money from people whose behavior ran counter to my ethics.

Is it true that you never accepted money for working as a lecturer and rector at the architectural college in Ahmedabad for more than 20 years?

I accepted it, but then funded scholarships for students. Teaching is a service to Saraswati, the goddess of education. It would be wrong to accept payment for it.

This year, the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein showed the first retrospective of your complete works outside of Asia. Do such honors only come when they’re no longer important?

No, I’m not old enough for such thoughts.

You’ve been married since 1955 and have three daughters. How does your wife see your life?

We’ve had our disagreements, but we still ask ourselves the same question every night: did we enjoy ourselves today? For 64 years, we’ve both answered “yes!”

Suppose one of your students asks you for life advice. What would be your answer?

I’d answer with a fable Le Corbusier told me. A starving dog asks a well-fed dog how he manages to get so much food. The fat dog answers, “Come back tomorrow, then I’ll tell you.” The next day the thin dog waits in vain. The day after that, he sees the fat dog and asks him why he didn’t come. “I wanted to come but my owner chained me.” “Does he do it every day?” “Yeah, why else would he feed me?” The thin dog told him to go away. It was better to starve, he thought, than for someone to put chains on him.

Credits

- Text: Sven Michaelsen

- Translation: Shane Anderson