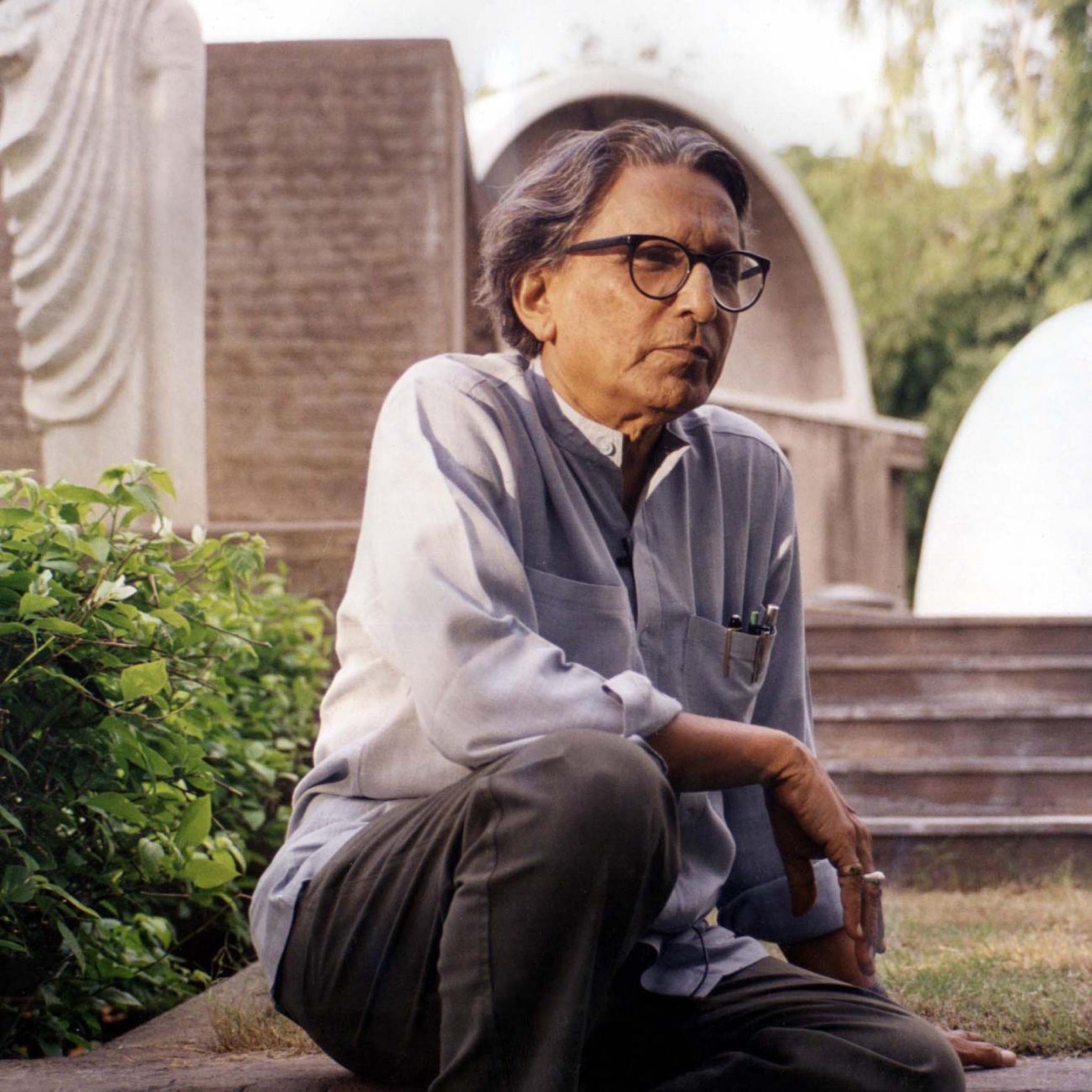

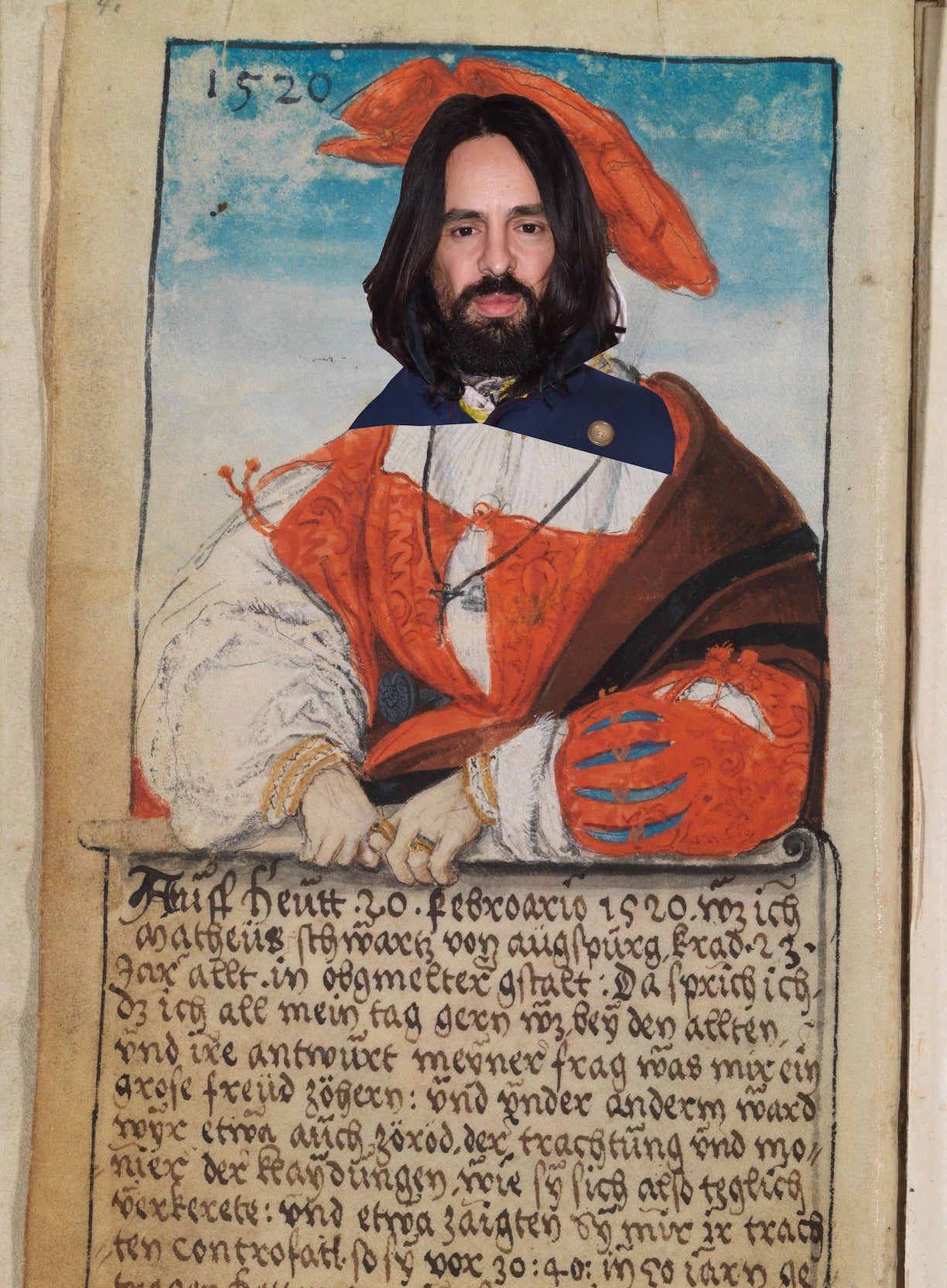

Collecting – and Celebrating – With Publisher BENEDIKT TASCHEN

|Sven Michaelsen

HAPPY BIRTHDAY BENE! In honor of publisher and collector BENEDIKT TASCHEN’s 60th Geburtstag, we’re celebrating with a look back to his interview with Sven Michaelsen in 032c Issue #35.

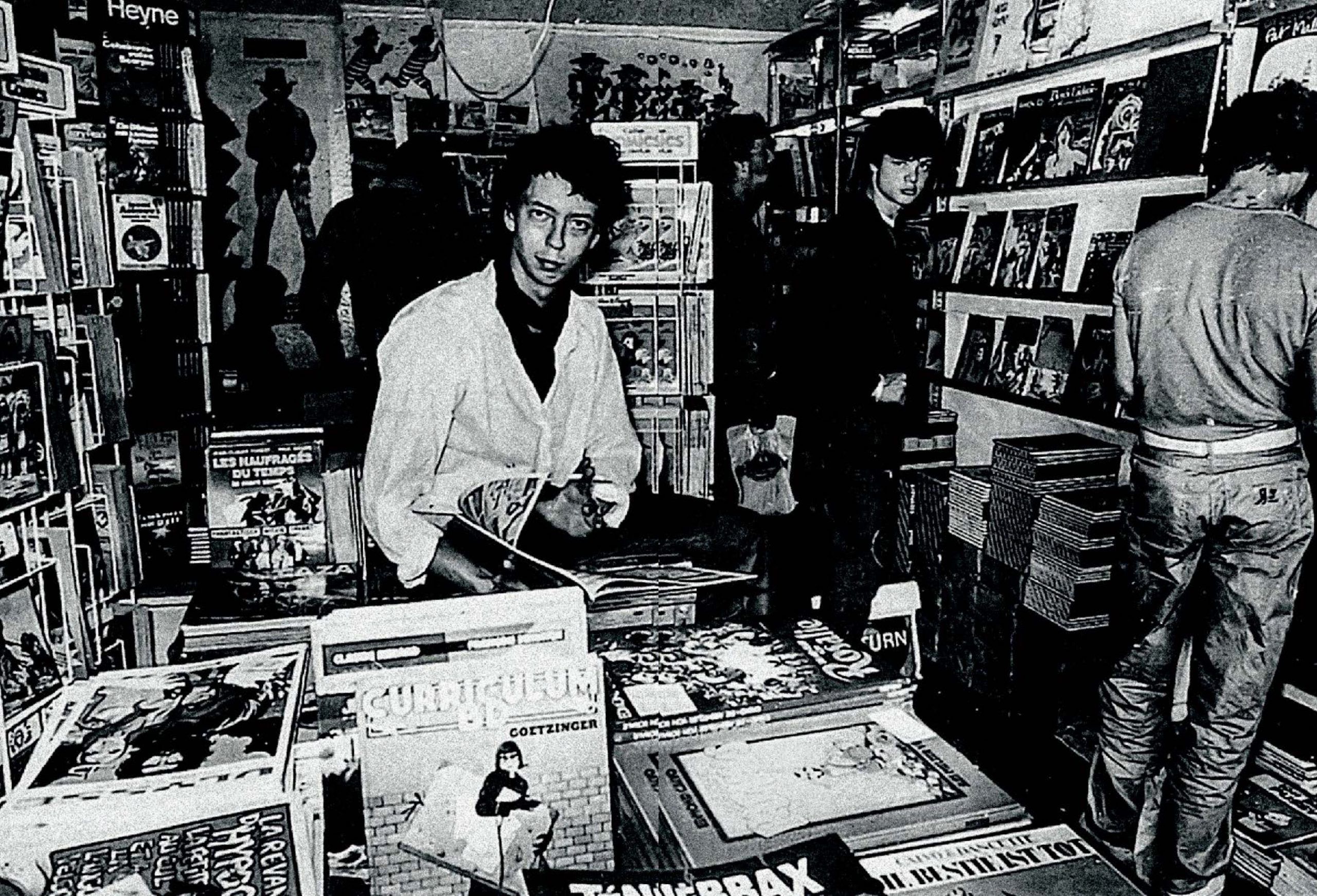

Benedikt Taschen has told his magical success story – one of a boy from Cologne who started out dealing in used comic books and ended up with the world’s biggest art publishing house – countless times. “The meaning of art in our lives is more stated than explained,” Taschen told me during a recent conversation at his Los Angeles home. “I can define exactly what art gives me: infinite enjoyment of life and a distinct sense of happiness for knowing that, in our disillusioned world, at least artists are able to communicate new ideas.”

Sven Michaelsen: Herr Taschen, is it true that your scholastic performance suggested you would lead a less than glamorous life?

Benedikt Taschen: I had a high school average of 3.4 [a poor mark in the German Abitur system]. I was often bored in class, and I thought it was completely excessive how much time school was costing me. I would calculate how much I had to do to just get by. It was a complex and calculated endeavor.

You also had disciplinary issues.

I had trouble waking up in the morning. My parents accepted that I would go to school at 11am, sometimes not even at all. I would type the note that would excuse me from class on my mother’s typewriter and forge her signature.

Sleep is underestimated, especially by successful people. When they say they’ve only slept for three hours last night, they feel like King Louis. I think it’s daft to view getting too little sleep as a macho attribute. For me, sleep is the foundation for everything. I sleep at least eight hours a night and rarely get up before ten. I can easily sleep for 12 hours.

It is said that you had a scary sixth sense for making money by the time you were 12 years old.

My parents were doctors. I told them they should fire their cleaning lady and that I would clean their practice going forward. I divided the rooms into specific squares and was done cleaning in an hour. The housekeeper had needed three hours. We spent our summer holidays in the Netherlands on the beach. There was a café there that stood on a wooden platform. I noticed that people often dropped coins down there when they were paying for their ice cream at the counter. Every day, I would lie down underneath the planks for two to three hours and wait for money to drop to the ground. I made up to three guilders in a day like this.

Do you have an erotic relationship to money?

No. Conventional luxury has never interested me either. For me, money is a means to an end. It’s helpful when you want to live an independent, autonomous life like I do.

When did you become an art collector?

When I was 24. A friend of mine who was a gallerist sold me a dozen artworks in 1985, among them a Hoover vacuum by Jeff Koons. I was lucky that in the 1980s, Cologne was the most important art metropolis in the world, next to New York. Crucial exhibitions took place right on my doorstep. If you wanted to, you could visit the studios of Sigmar Polke, Albert Oehlen, Günther Förg, Gerhard Richter, and Martin Kippenberger.

You own the world’s largest Kippenberger collection.

Martin Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen were my first focal points as a collector. Later, Günther Förg, Mike Kelley, Christopher Wool, and Jeff Koons also came in.

“Unfortunately, I’m not an artist – at most, I’m a master at the art of living.”

Kippenberger was known to many as half insane and totally egocentric. When he was at a table with important museum people, he liked to fart or serve After Eight after-dinner mints as appetizers. He gave his works nonsense titles like Aschenbecher für Alleinstehende [“Ashtray for Single People”], Sand in der Vaseline [“Sand in the Vaseline”], Arafat hat das Rasieren satt [“Arafat is Sick of Shaving”], or In Ibiza kann man Essen, aber in Essen nicht ibizen [“In Ibiza One Can Eat (‘Essen’), but in Essen One Can’t Ibiza”].

On one hand, he was exceptionally charming, warm, and generous; on the other hand, he looked for weaknesses in every person and made jokes at their expense. He did not care at all for the boundaries of civil decency. He was driven by the idea of turning his own life into art. Not everyone is able to bear that.

Kippenberger drank Cuba Libre, vodka apple juice, or Bloody Marys for breakfast. When he died of liver cirrhosis in 1997, at only 44 years old, it was like with James Dean: adulation and fame only set in after his death.

James Dean became a myth right after his death. With Kippenberger, it took almost a decade. I was still able to buy major paintings of his years after he died. You could have bought the same self-portrait that was auctioned off at Christie’s New York in 2014 for 19 million dollars for 100,000 dollars in 1997.

When Jörg Immendorff was caught by police in a luxury Düsseldorf hotel with nine prostitutes and 21 grams of cocaine, he said that painters needed “a certain measure of orientalism.” Is the excessive artist type, à la Immendorff and Kippenberger, becoming an obsolete model?

No. Artists who work as though their survival depends on it will always exist. A part of being an artist is feeling lonely, experiencing self-doubt, and having the urge to constantly reinvent oneself. Such a life isn’t easy, which is why so many have an urge to pursue intoxication and excess. The difference is that nowadays a lot of artists place value on being seen with the right people in the right place. I often ask myself when they find the time to work during all this networking.

One of your lucky moves as a collector was that you bought works from Jeff Koons’ 1989 series Made in Heaven. Among them was Ilona with Ass Up – a monumental sex scene that hung in your office for many years. How much did you pay for it?

Two hundred thousand dollars. That was an exorbitant amount back then. A decent Warhol cost about 100,000 dollars at the time, a Kippenberger between 20,000 and 30,000 deutsche mark. Many dealers and collectors said: “This Taschen guy must have a screw loose, because neither Kippenberger nor Koons are good for anything. Nobody wants to have anything to do with this stuff!”

In 1992, Koons had some money troubles following his divorce from Italian porn actress Ilona Staller, and he sold some of his pieces. You did not hesitate to buy.

I went into a lot of debt to purchase these masterpieces, but in the end, I got the money back. I dropped 1.2 million dollars so I could acquire key pieces by Koons, including Michael Jackson and Bubbles [1988] and the “rabbit” sculptures. Then the American billionaire Eli Broad bought them. Today, they are crowd magnets in his museum – The Broad – in Los Angeles.

What are those pieces worth today?

Maybe one or two hundred times as much. But one could also have bought Amazon shares when the company was founded in 1994. These types of calculation games don’t do any good.

One of Kippenberger’s pieces has the beautiful title Selbstjustiz durch Fehleinkäufe [“Vigilante Justice by Failed Purchases,” 1984]. How important is it to you that an acquired work eventually proves itself to have been a smart investment?

Collectors who announce with utter conviction that the increased value of their paintings doesn’t interest them either bought the wrong paintings, or they’re lying. But this doesn’t mean that they approach buying art like investment bankers who are thinking about profit margins. I’ve been living with my artworks for more than 30 years, and I am very lucky that the market is interested in them as well.

Was there a purchase where the artist kept you in suspense?

David Hockney is my friend and neighbor. I visit him twice a week in his studio. A few years ago, he started painting a piece that I very quickly knew I absolutely had to have. When he was finished, 12 months later, I asked him to sell it to me. He shook his head and said, “I love my paintings, and thank god I’m wealthy enough now that I don’t have to sell them.” A game started between us, half fun, half serious. Two years later, he finally sold it to me after all.

Do you have a golden rule for newcomers who, without being able to afford an art advisor, want to build a collection?

Unfortunately, no. But maybe the advice of my friend Simon de Pury, who was the longtime chief auctioneer worldwide at Sotheby’s and now works as an art advisor, will help. He says that one should look at what the artists themselves are collecting. They have the most schooled eyes of all, and their eyes can see the future.

The author Martin Walser sneered: “When art stopped having to be mastered, it started suggesting. The invention of the 20th century: the artist is the art.” Does an artist have to appear with a story nowadays in order for their art to be marketable?

I don’t need a story, but the art market does. It can be helpful for an artist to attract attention with an adventurous sounding resume. But it doesn’t make the work better. The more time passes, the clearer it becomes as to whether an artist has created something meaningful or something that will remain a footnote. It doesn’t matter if someone’s private life is boring or sensational if the work is assessed in this way.

When Koons married Ilona Staller in 1991, he married a woman who had acted in porn films for years. Do you think this was a marriage of love or a staged performance piece?

Jeff introduced me to Ilona in the late 1980s, when they were both living together in a rented Biedermeier apartment on Munich’s Knöbelstraße. This encounter led us to make a book with her, and she later sang at our party at the Frankfurt Book Fair. I am certain that Jeff was in love with her. The fact that she was also his muse was just an extra addition.

Art star marries porn star: was this the moment of ignition in Koons’ media strategy for becoming the most popular artist of his time?

No. Jeff’s self-staging had begun long before his marriage to Ilona.

Hypothetically, had Koons presented his work under a pseudonym and never revealed his persona, would he have become as famous and expensive as he is today?

No. But Jeff is an exception because he is able to speak about his work eloquently and with complete conviction – a talent that very few people possess. He knows what he is doing and how it is received, without being calculated or opportunist about it.

Do you buy works by artists who you privately think are assholes?

This happened to me once. Every time I walked past this artist’s piece in my home, I was in a bad mood. I separated myself from all of the works I had of his.

How often do you buy art?

Every month, sometimes more often than that.

Collectors are usually driven by a desire to show off. Why have you only exhibited your collection once?

I was offered to show my collection in Madrid in 2004. I knew the curator, and she was representing the Museum Reina Sofia, a first-class institution – that’s why I accepted. There have been other requests since then, but exhibiting a collection is an enormous production.

Every collection presents a psychoanalysis of the collector. What do your art pieces say about you?

I have to like a work of art. I have to find it important and feel a connection to the artist. Take the works by Kippenberger, Oehlen, and Koons – they communicate with each other about the fundamental questions that concern my generation. I feel like I’m in good hands in this group analysis.

Sigmund Freud said that collectors are compensating for an emotional deprivation experienced as a child – those who missed the love of a mother search for warmth and security in objects later in life. Does this apply to you?

No, I did not miss out on anything on an emotional level as a child. But while we are on the subject of Sigmund Freud, it is difficult for me to comprehend how one would be able to separate a gut decision from a logical decision when buying art. For me, this is decided in unison, by the mind and the gut – and sometimes other regions of the body are involved in the decision making as well.

Shortly before his death, Picasso collector Heinz Berggruen confessed that his obsession for collecting made him a deeply unhappy human being. He compared himself to a heroin addict who spent his life restlessly looking for dope. Are you familiar with this feeling of ravenousness?

I would call it desire, or passion. Then again, if you look at the regularity with which I buy art, then I guess I am also a junkie – a happy junkie.

For many collectors, the question of “being” is also a question of “being there.” How important are the high society parties in Basel or Miami to you?

Everyone is different. I don’t care much about this fancy party circus. It’s enriching for me to talk to artists in their studios, and to be able to watch exceptional people like David Hockney, Albert Oehlen, and Jeff Koons in their daily process of creation. A lot of books we publish at Taschen originate in this way.

Is it true that you gifted your children art for their birthdays when they were little?

Yes. They got what was around our household: a Kippenberger, a Koons, or works by young artists who were at the start of their careers. Sometimes there would be a fit because one kid would have preferred a Barbie doll over a Kippenberger. But they had to go through this valley of tears. You don’t always get what you want in life.

You are currently in your third marriage, this time to an American woman who built Art Basel Miami alongside Sam Keller. Three of your five children are adults –

And are involved in art! I passed the management of the publishing house to Marlene in early 2017. Charlotte is an actor and takes care of Taschen in Los Angeles. My son Bene oversees a gallery in Cologne that represents photographers and painters.

Insider trading, price manipulation, cartels: things that get you into jail anywhere else are common practice in the art world. Is this a moral conflict for you?

I don’t see it that dramatically. There is a law in the art world that exists in all other markets too: when there’s a lot of money involved, people driven by greed show up and don’t abide by the rules. Anyone with a functioning radar and a little knowledge of human nature recognizes these vultures from a mile away. What I’ve liked about the art world since day one is that you can close a deal with just a word. That is a beautiful anachronism. Anywhere else, you have to sign a 50-centimeter-deep stack of documents in the presence of a notary.

What are the reasons behind these anachronisms?

The art market consists of a small circle of people. I’ve known the essential dealers and collectors for years. It’s about one’s own reputation. If your reputation is doubtful, that information will spread like wildfire.

Are you repulsed by, for example, an oligarch’s wife who will quickly grab a Basquiat or a Bacon on a power-shopping spree?

No. I don’t sneer at hedge fund managers who buy art either. The art world wouldn’t work without young collectors with new money. The new billionaires from Eastern Europe or Asia may not be as experienced as someone who has been in the game for 30 years, but many of these people are incredibly smart, thoroughly informed, and extremely quick to learn. It is astounding in what short time they are able to build respectable collections. One also shouldn’t forget that it was the nouveau riche who acquired the big art collections of the early 20th century – from impressionism to the classic modernism of Picasso and Matisse. Or take the Frick Collection in New York: it was payed for with the coal and steel millions amassed by Henry Clay Frick at the end of the 19th century – he was young money as well. He started out as an apprentice in a grocery import store.

“I don’t need a story, but the art market does.”

There are three artists on Manager Magazin’s list of the 1,001 richest Germans. Gerhard Richter is ranked number 220, with a fortune of 700 million euros. Neo Rauch and Anselm Kiefer share spot 935, with assets worth 100 million euros each. Are you astonished that you can get this far with a brush?

If it were up to me, there would be a hundred artists on that list. The fact that there are only three is a pathetic display, considering the inspiration and vision they give us.

Axel Springer CEO Mathias Döpfner established a museum in Potsdam to house his collection of erotic art. Would something like this ever appeal to you?

Maybe. My collection is scattered across half the globe. To have it all in one place would be like a reunion of old friends who you haven’t seen in many years.

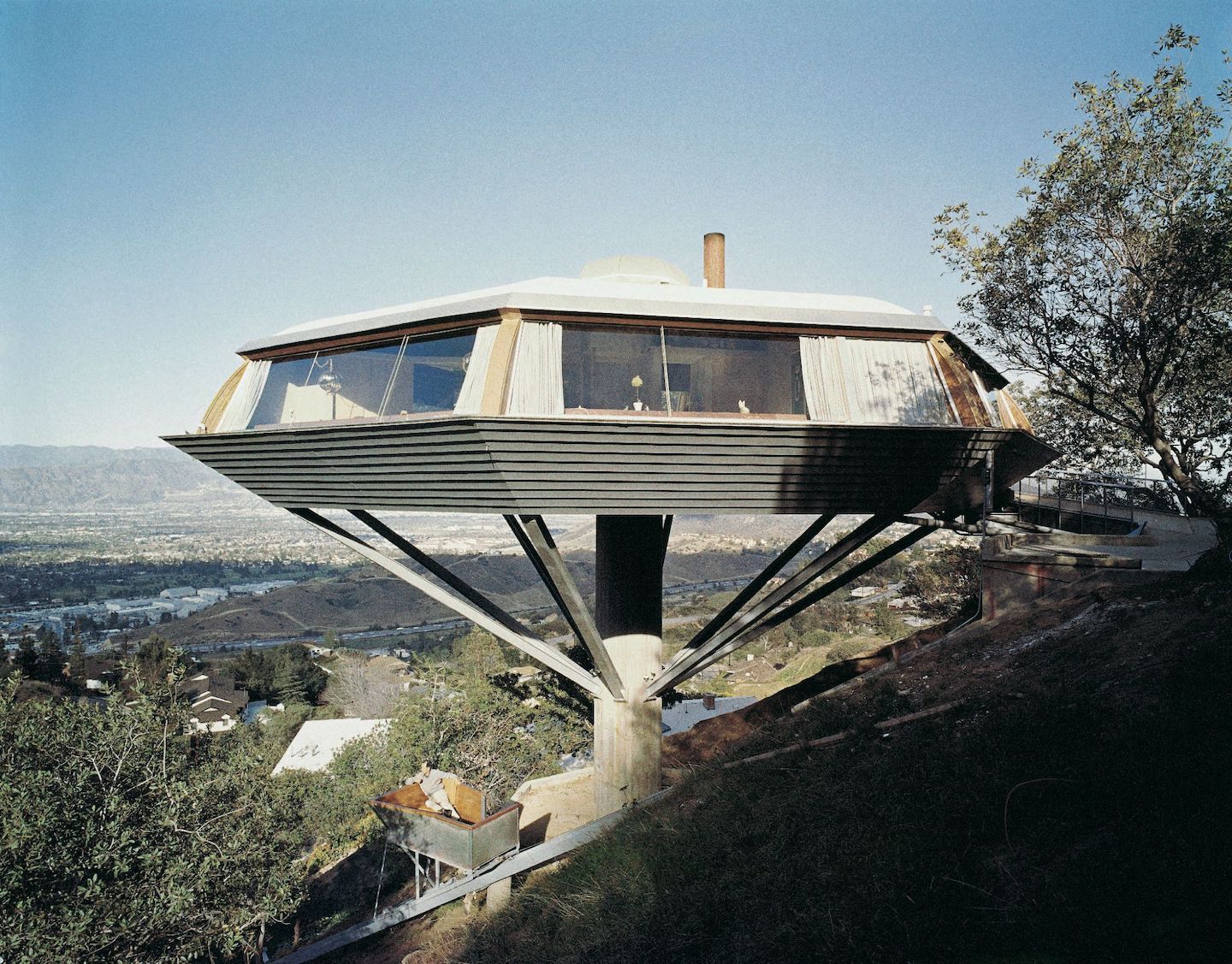

At 57 years old, you’re at an age at which many successful people start working on their positioning in the afterlife. Will you build your own museum to immortalize your name?

I have no idea.

Which city would you prefer for your potential museum?

Los Angeles. I live here.

Your hometown, Cologne, goes without?

I’m rarely there. The arrival of my paintings would take too long.

Your publishing house sells 20 million books a year. The turnover is estimated at 300 million euros. What would be worth more in a sale: your publishing house or your art collection?

I don’t know. Both are equally valuable and important to me, even if the publishing house takes more work than my art collection.

Have you tried to be an artist yourself?

I used to sketch and paint a lot – mostly vampires. One day, I positioned myself at the entrance of the Cologne art fair –

Today’s Art Cologne.

And I offered my paintings for sale on the sidewalk. Two days later, I had made more sales than some gallerists in the hall itself.

How old were you back then?

Nine. But, unfortunately, I’m not an artist – at most, I’m a master at the art of living.

Five children, a prosperous publishing house, a legendary art collection, and no less than three houses in the Hollywood Hills: your path of success has been on the up and up since your childhood. Do you have a theory about who or what is responsible for your good fortune?

I was born under a lucky star and have a positive-fatalistic attitude to life. You can’t force anything. The saying that man is the architect of his own fortune is sheer nonsense to me. Only one out of a thousand people will have a big career, and this is most certainly not because they’ve worked extremely hard. Successful people tend to dramatically overestimate their own stake in their success. That’s why there are so many posers and snobs among successful people. Those who have been very lucky in life shouldn’t constantly try to convince others of how great they are.

With which sentence would you end your autobiography?

“Fortune favors the brave.”

Credits

- Interview: Sven Michaelsen

- Images: Taschen