The Book of Gucci According to Alessandro Michele

|Michael Ebert and Sven Michaelsen

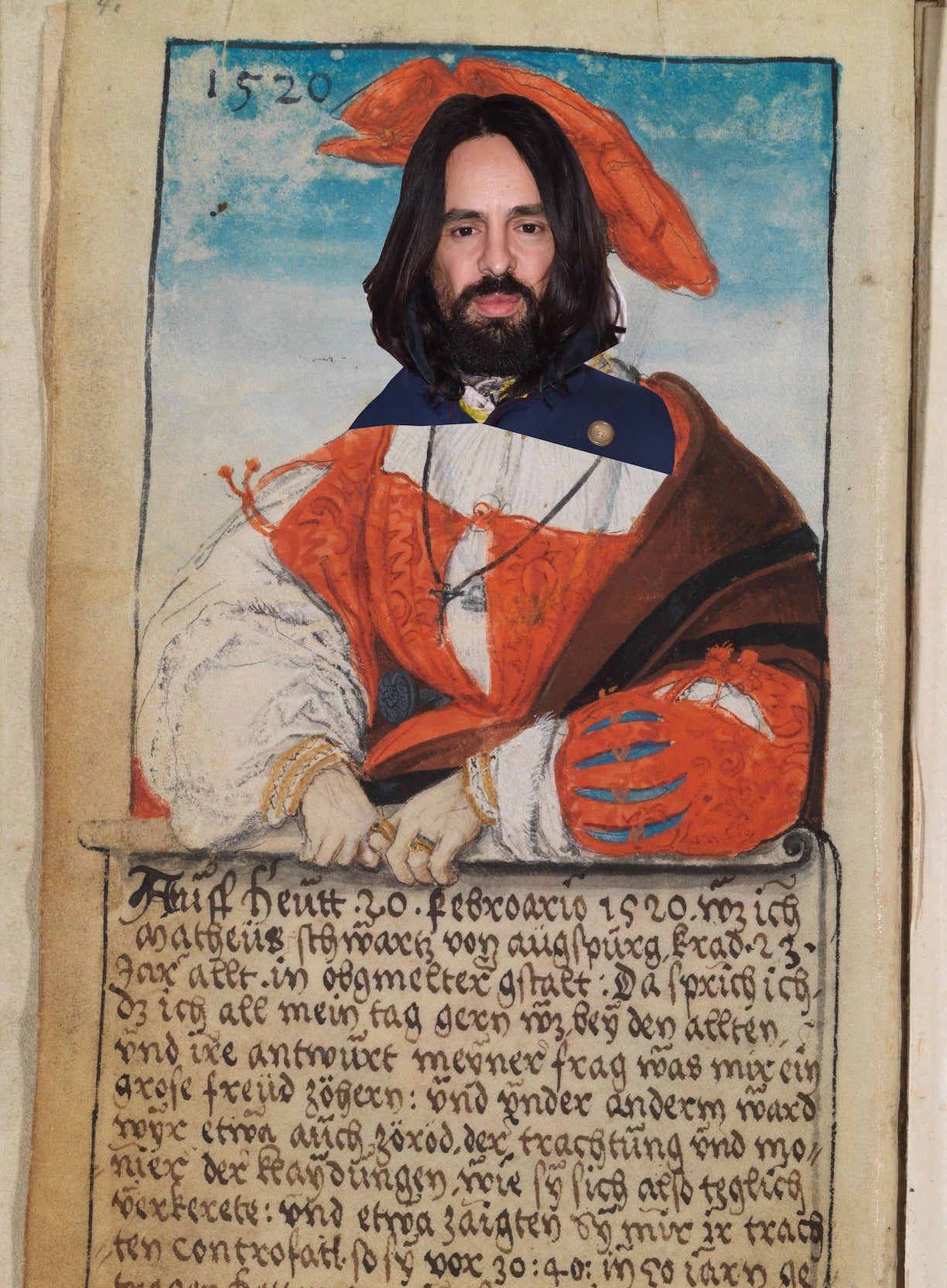

After twenty years with Gucci, and seven years as their creative director, Alessandro Michele will be leaving his post at the iconic Italian luxury brand. Michele, whose pool of reference ranges from medieval manuscript drawings to long-forgotten Hollywood B-movies, undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the brand. This week, Gucci bid Michelle arrivederci in the wake of lukewarm growth under his tenure, ending an era for the longhaired Roman, who Sven Michaelsen interviewed for 032c in 2018.

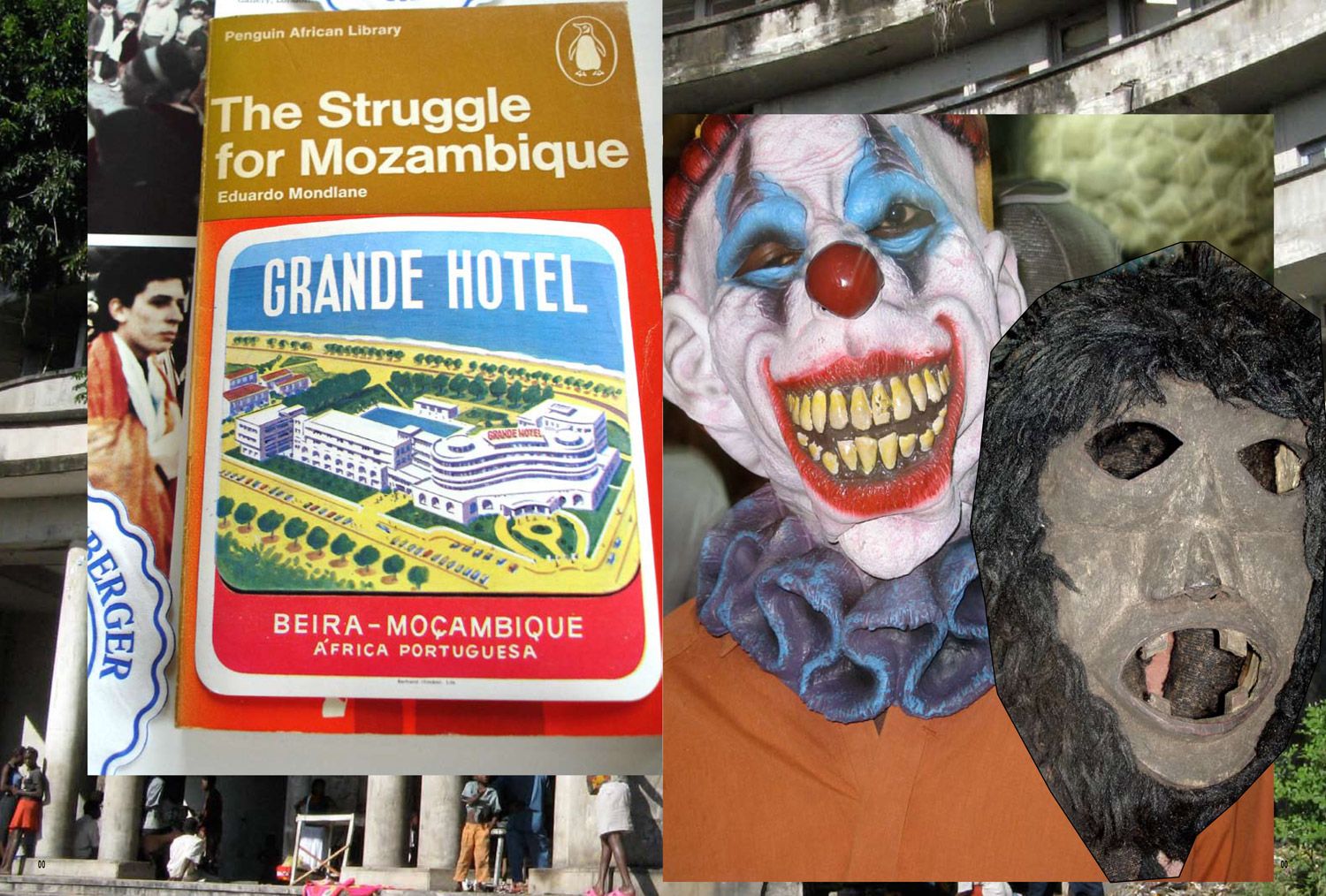

Alessandro Michele’s arrival as Gucci’s creative director was more like an alien invasion than a typical fashion coronation. It was fast. Overwhelming. Utterly strange and world-dominating. The strangest part was that it all came from Planet Earth. Michele’s kaleidoscopic menagerie of references – from antique artwork to funerary artifacts to B-movies – are all probed from the found objects he collects on a near-compulsive level.

It was at Michele’s apartment in 2014, while sitting among the objects in the designer’s private Wunderkammer, that Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri decided that the company’s long-time handbag designer should become its creative leader. The choice came as a surprise to all involved, including Michele. In retrospect, however, it feels inevitable that a man so wrapped up in the lives of things would be placed in charge of the world’s new ones. Michael Ebert and Sven Michaelsen visited Michele in Rome to discuss the burden of vanity, the terror of symmetry, and the faith of being devoted to objects.

You once said: “Fashion is like an old lady lying on her deathbed. I think we should let her die.” Why would a fashion designer welcome the death of fashion?

So that she can be resurrected. Fashion has become a prison with thick walls, and I’m restoring its creative freedom. Great fashion was done in the 1990s. Even the ad campaigns were masterpieces. The only fashion produced after 2000 was whatever promised the highest profit. The marketing director would march over to the designer and say, “This spring, we’re going for pink, because pink is selling well in Asia right now. Our second focus is blue because blue is selling well in the United States.” The system is sick when marketing dictates to a designer about what his or her fashion should look like. Fashion comes first, then the strategy for how to sell it. Fashion dies when it’s the other way around. I design the craziest things at Gucci without anybody butting in—and sales go up.

What sets you apart from your colleagues?

The fashion world is a bubble where everyone resembles everyone else. Fashion designers read fashion magazines, eat fashion meals, talk about fashion in interviews, and when they need advertising images, they hire a fashion photographer. Every few years, someone appears who doesn’t abide by these conventions. When I experiment with a material, it’s like a psychotherapist’s session. If it’s the right material, it will pop a cork in me, and my inner eye sees how images and cultural symbols from different eras collide. My fashion stems from this jumble. You could call it eclecticism. I’d rather say I’m preparing a fruit salad of beauty.

The clothes you design for women are also worn by men and vice versa. If Martians landed on Earth and asked you to explain what masculinity means, what would you tell them?

I would say, “Sorry guys, you’re asking the wrong person.” At best, I could say that people used to be divided into two bipolar genders, but they aren’t anymore. The ambiguous has replaced the unambiguous. It’s like a color palette: anyone can choose the hue that suits their sense of self. My grandfather and father were dressed like little girls at their communion, with long dresses and roses in their hair. For years I walked past a statue at a museum in Rome that had a woman’s face and body. The disconcerting thing was that it also had a penis. I thought, okay, a hermaphrodite. But one day I stopped and read the sign next to the statue. It was Venus, the goddess of beauty. In classical Greek and Roman culture, beauty was created through the combination of feminine and masculine. The Catholic Church eradicated this heritage with fire and sword. My fashion aims to revive it.

Tom Ford—the Texan designer who turned Gucci from a sleepy, bankrupt legacy company to a money-making machine in the 1990s—considered sexiness the number one fashion priority for women. Would you agree with that?

Tom is still Olympus, but the word “sexiness” sounds old-fashioned in my world. Beam with joy, smile sensuously, move elegantly, tell an exciting story, express an interesting thought, resist the terror of symmetry—then you are desirable.

What do you mean by the “terror of symmetry”?

Real beauty is based on asymmetry. But we are about to obliterate any asymmetry, because people want us to believe that symmetry is more beautiful. But regularity is synonymous with boredom. I have been accused of using unattractive models. Anyone who thinks like that is still living in the 90s. My casting criteria are the stories a model tells with her face and body. These stories make a person unique, and that’s what it’s about today. Everyone wants to be unique. Tom’s models were blonde beauties, but we live in the age of Instagram. Nowadays, almost anyone can look like a Hollywood star with an image editing app. Instead of an agent, all you need is an Instagram account. The stupid thing is that the Olympus of beauty is no longer an elitist, lonely place. You’ve got the masses frolicking around there.

You are 45 years old. Are you a fan of media like Instagram?

I’m rather skeptical, but that’s a generational thing. At my age, a person is manipulated by social networks rather than manipulating others with them. Being on Instagram at 45 feels like being 80.

When Tom Ford became the creative director of Gucci, he ordered all employees to use black pens. When someone expressed a desire to keep his yellow pen, the pen was photographed and the image faxed to Ford for a decision. Are you like that?

No, I find breaches more inspiring than flawless aesthetics. Look at what I’ve got on. I’m wearing knee socks made of thick wool with sandals. I like clothes that look like they’ve been worn for years, so I have them wash new things until they have a vintage look. Whenever I give something to someone to iron, I say the things should look like they’ve been lying in a suitcase for a few days.

Explaining your collections, you often cite little-read intellectual giants like Gilles Deleuze, William Blake, Novalis, Roland Barthes, Giorgio Agamben, Martin Heidegger or Roger Caillois. Are you really that highbrow or is this the influence of your life partner Giovanni Attilli, an urban planning professor whose nickname “Vanni” is tattooed on the inside of your upper arm?

Vanni is a great teacher who opened my eyes to the fact that a dress can just as easily convey a thought as a poem, a philosophical essay, or a Peanuts comic by Charles Schulz. “Fashion is digested sociology,” Vanni says. You can use clothing to demonstrate approval or protest, just like you would use a political banner. That’s also part of fashion’s power.

Is your boyfriend interested in fashion?

When we met in 2007, he had the smallest wardrobe and the largest bookcase I had ever seen at a man’s home. His circle of friends consisted of poets and intellectuals who often used the word “authentic.” It was part of their noblesse oblige to reject fashion and buy only cheap goods off the rack. When I told them that anti-fashion was also fashion, there was a dispute. I think it’s vanity turned inside-out whenever someone tries very hard to look as though they have made very little effort. I think only a farmer who gets up to milk his cows early in the morning doesn’t think about his appearance in these moments.

Vanity is a burden. Do you envy people who don’t care about their appearance?

Yes and no. It’s humiliating to stand in front of a mirror wracked with self-doubt. On the other hand, vanity is the strongest productive power I know. It keeps the world buzzing because it incites people to want to be beautiful and to impress others. Without vanity, there would be neither seduction nor rockets flying into space. I saw the exhibition marking the 300th birthday of Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The beauty of the antiquity collections was overwhelming. I would have gotten a bed in there and camped in the halls for three days if I could. The things Winckelmann wrote about perceiving beauty in art struck a chord with me. Looking at beauty is like a healing medicine, but it also has a painful sting because it shows us how imperfect we are in comparison.

Being a creative director in the fashion industry is a hot seat. Are you good at withstanding pressure?

Yes, because I don’t worry about what other people expect me to do. And I wouldn’t be surprised if Gucci fires me in 2019. I don’t believe the future exists anyway. It’s a vintage idea, almost medieval.

Doesn’t a fashion designer have to know now what people will want to wear in half a year?

Your colleagues will kill me at some point, because I don’t know. I’m not a magician who can look into the future with a crystal ball. I only know what I want in this second. I’m too old to put on a mask and make it my face. Young people invent versions of themselves that they consider attractive and promising. After 40, you want to live in sync with your soul.

You grew up in Monte Sacro, on the outskirts of Rome. You’ve said of your youth that you felt “like a child of Lana Turner and Francis of Assisi.”

My father was a technician for Alitalia, the airline, but his true vocation was sculpture, music, and poetry. He played more than ten instruments and wrote poems and stories. Officially he lived with my mother, but he spent most of his time in his studio like a hermit. He lived without watches, had a long beard and hair down to his belly button. He looked like a shaman and often talked to the birds. At some point, I gave him a mobile phone for his birthday, but he never used it. Once, when I was a little boy, I asked him when my birthday was. He didn’t remember the date or the year I came into the world, but he remembered exactly how the light in Rome looked on the day I was born. You couldn’t wish for a better father than him, because he was one of those people who make you feel that no matter how you turn out, or in what direction you develop, his love would follow you.

Why did your father live without watches?

He declined to divide the time into minutes and hours and to take orders from clocks. That’s why it was almost impossible to arrange to meet him. He seemed more and more like a saint to me in his last months. He didn’t mind dying at all. As we said goodbye, he said, “It makes me very happy that we shared so many seasons together. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case with my father and me.”

Is your mother still alive?

No. She worked for a film production company, as an assistant to the managing director. She loved big city life and adored old Hollywood movies with divas like Lauren Bacall or Bette Davis. Her eyes shone when she talked about the dolce vita in 1960s Rome. She was an early feminist who married at the age of 30. That was ancient for a bride in those days.

When did your parents die?

I don’t know that exactly, because I inherited my father’s relationship to the past. I guess they’ve been dead for a good ten years. But they’re still with me to this day because they embody my two halves. I inherited a deep connection to nature from my father, and the love of beautiful appearance from my mother.

What were you like as a teenager?

I had a big ego and wanted to seem as cool as possible. I took no for yes and rebelled without knowing what I was rebelling against. At 12, I dyed my hair blonde with bleach from the bathroom and surrounded myself with the worst guys in the neighborhood for six years. I was drawn to the hidden and the forbidden. Thankfully, drugs were so common back then that they didn’t interest me. Otherwise, I would have died long ago. My mother was always being called into school because the teachers wanted to know what was wrong with me. But I was just a confused teenager playing guitar with his buddies for hours on the Spanish Steps, not knowing if he wanted to become a world-famous painter or a world-famous rock star. My parents left me alone, thank God. You seem to have guessed what I mean. Some people think of me as a loopy bird of paradise, but I get my stuff in line. If I were incapable of concentration and control, then Gucci’s profit wouldn’t have gone up 40 percent last year.

When did you start to be interested in fashion?

My mother had a twin sister who was just as fashion-crazy as she was. As a young boy I would watch them get ready and gave my verdict. As with almost all gays, my feminine side is particularly pronounced. It made me proud when my mother left the apartment in the evening wearing a chic fur coat to attend a cinema premiere. I imagined she was on her way to a fancy-dress ball at a royal palace.

After you studied costume design, you mostly designed handbags at Gucci for 12 years. Did it ever get boring?

I felt the same about Gucci as my father did about Alitalia. I just worked instead of creating something that has a soul and speaks my language. When I wanted to quit at the end of 2014, my phone rang. Marco Bizzarri, the new CEO of Gucci, wanted to talk to me about optimizing workflows. It must have clicked with him during the four-hour meeting in my apartment, because although he had left with a non-binding “We’ll be in touch,” he asked 20 days later if I could pluck a collection out of thin air within a week. The offer was crazy, but on the other hand, passion is more important than time. I said yes because I thought, “What the hell, you want to work somewhere else anyway, so give yourself the freedom to make a mess of it.”

They say your apartment is filled with curiosities you purchased at auctions and at flea markets. Was it your decorating style that got you appointed Gucci’s creative director in early 2015?

Yes, I am convinced of that. When Marco came to me, he asked in amazement, “Do you live in these rooms, or is this some kind of museum?” I’m staging my life to make it a work of art, and that means down to my gorgeous house shoes.

We are having this conversation at your office in Rome, which is located in a stately 16th-century palazzo near Castel Sant’Angelo. From your desk you can see stuffed canaries and peacocks, preserved turtles, the severed heads of old porcelain dolls, Madonna with child figures, skulls, golden crowns, a tattered stuffed lion, and a toy train car sprayed with graffiti. Explain this arrangement to us.

What you see here are objects that I recently purchased. I live with them for a few weeks, then have them restored and taken to a warehouse. I would like to surround myself with them at home, but people who live with another human like I do have to rein in their obsessions—or they’ll be single again very quickly. Not a day goes by that I don’t buy anything, and often the objects are very big. That’s why there is hardly any room left for Vanni and me in our home.

Your boyfriend once complained, “It smells very old in our apartment.”

That’s true, but Vanni knows I can’t change anymore. I collected shells, stones, and pressed flowers as a six-year-old and arranged them into little artworks. I became a serious collector by the age of 25. Collecting is like a disease that gets worse and worse every day, and there is no medicine that can help. Whenever I discover a damaged antique, I hear a voice from within telling me, “Take me home with you and nurse me back to health!” Every old object has a story to tell, and I seem to be the only one who wants to hear it. Sometimes I tear up when an object lands in the garbage before I could give it a place in my hospital.

Which object in this room speaks loudest to you?

The eight mourning rings I’m wearing on my fingers. Look, the rings have embedded likenesses showing the face of a child who died early. These miniatures are like magical Polaroids to me. I imagine the doting mother sitting at her child’s deathbed, letting out heart-rending sobs. In such moments, I believe those children’s souls live on in my rings.

If you could take one thing with you when you die, what would it be?

My magic mushroom. Whenever you have to cry with sadness, you burn it. Then it cries for you and you’ll be happy again. Vanni got this mushroom from a shaman and gave it to me as a present. That symbolic gesture is what made me fall in love with him. Back then I felt like crying every day, but with Vanni, Neptune came into my life, the god of flowing waters and leaping springs, and all was well. Sometimes I think he is the reincarnation of my father. My father didn’t give me any medicine when I was sick as a child, but treated me with mushrooms and herbs. That’s why Vanni felt right from the start.

On what occasion did you get the mushroom as a present?

It was my birthday, and I celebrated with a big party in a friend’s apartment. Vanni stood in the doorway with a fever and said he needed to take off soon, but first he wanted to give me something. He took out the mushroom, explained its powers, and said goodbye. I placed the mushroom on the windowsill in the kitchen, but half an hour later it was gone. Someone had thought it was garbage and had thrown it in the trash. When the party was over, I dumped all the garbage bags on the floor of the living room and started digging. Three hours later, I found it.

You’ve become known for your long hairstyle that resembles representations of Christ. How did you come up with that look?

I had long hair even as a toddler. My mother would just trim the tips of my bangs. After being a blonde from 12 to 27, I had a new hair color every three or four months, from green and eggplant to orange and ginger. I’ve had the dark hair I had as a child since my early 30s. When I became creative director of Gucci, I worked so much that I had no time to go to the salon. So the resulting Jesus hairstyle became my trademark. A year-and-a-half ago, I had my hair cut shorter so that I wouldn’t look like my image anymore. Who knows, maybe I’ll go back to blond again soon. I am fascinated by hair, because those familiar with the Mediterranean region’s classical history know that it stands for power, beauty, health, and physical strength.

How many sit-ups can you do?

Not even 20. My dad thought that a healthy soul required a healthy body and encouraged me to play basketball, but I never became an athlete, unfortunately. I have a personal trainer to compensate for all the sitting, but I see him far too rarely. Yoga and meditation aren’t my thing either. I talk too much to be able to focus on my breathing.

How would you dress if you had to go before God today?

I would wear something comfortable, because it would be uncomfortable to meet God. But that would be boring. I would wear something dazzling that glistens and sparkles like a starry night. God and glitter, that sounds promising. I would be barefoot, get a curly hairstyle, and wear my favorite suit from the 1970s. It has bell-bottoms that make you feel like a king. Since I am a Renaissance person, I would have the suit decorated with magnificent embroidery. The motto will be: Fashion god of the Seventies meets the greatest fashion designer of all time.

Credits

- Interview: Michael Ebert and Sven Michaelsen

- Paintings: Narziß Renner