Sculpting in Time: WILLEM DAFOE on Being “Inside”

|Victoria Camblin

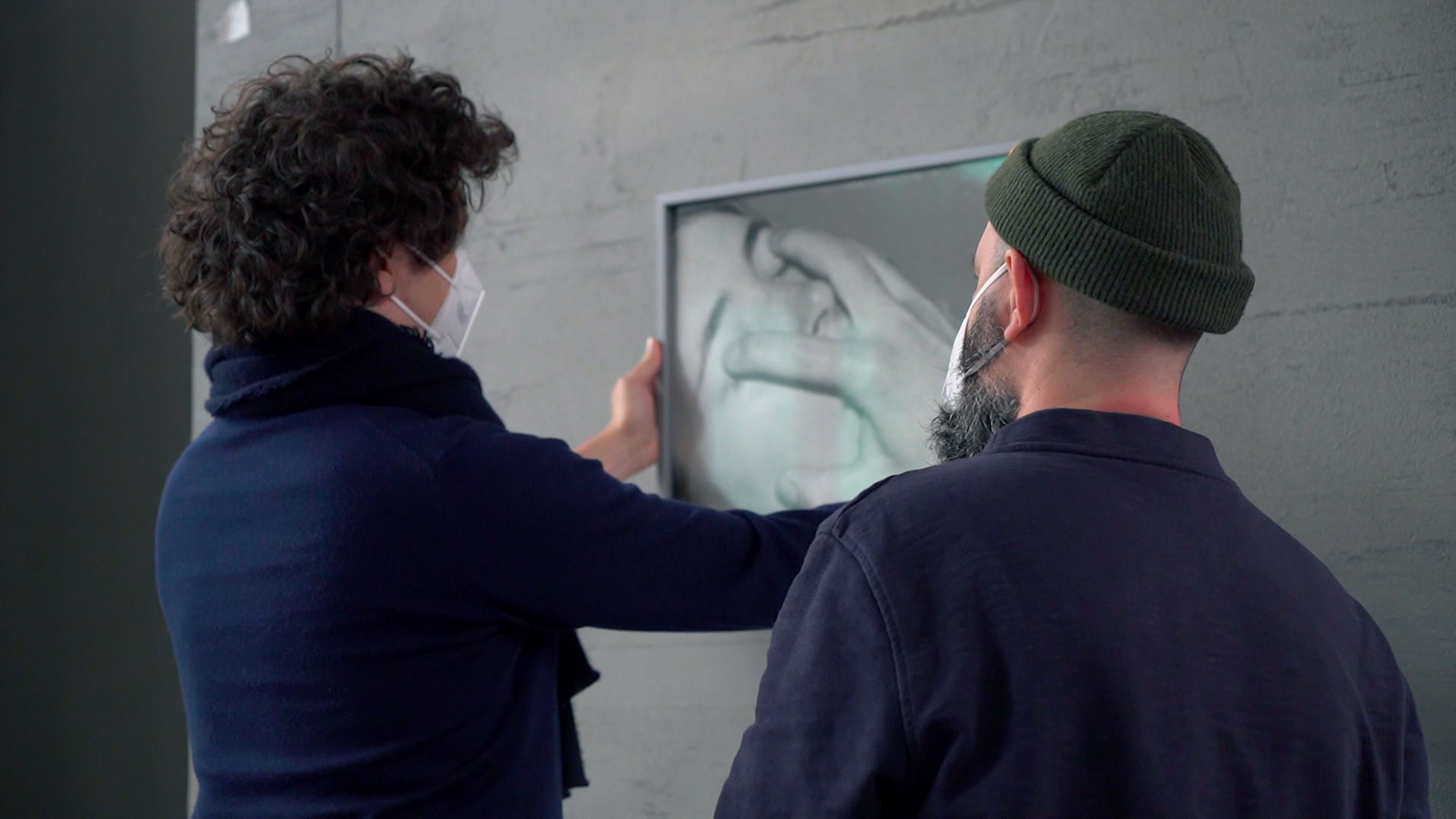

Vasilis Katsoupis’ debut feature, Inside, stars Willem Dafoe as Nemo, an art thief marooned in a Manhattan penthouse after a heist goes wrong.

A sophisticated and seemingly well-funded plan gets him in front of the target: a vast collection of modern and contemporary art, blue chip and emerging. But the Egon Schiele self-portrait isn’t where it’s supposed to be. He can’t leave without it. Then he can’t leave at all. The “smart” home security system short-circuits, sealing the exits and cutting the phone lines and water supply. What ensues is in many ways an archetypical tale of survival. A man, alone, confronts his harsh environment—here, a desert island he shares with works by Francesco Clemente and Maurizio Cattelan—and in so doing comes to know himself.

The art, ostensibly, is what makes Katsoupis’ take on the Robinson Crusoe format distinctive. The name Nemo is Latin for “nobody,” and what Dafoe’s character goes through in Inside might be described as a process of annihilation, achieved by means of artistic creation. "All creation is a drawing-up (like drawing water from a well)," Martin Heidegger writes in The Origin of the Work of Art. Nemo certainly draws. He sketches in a small book—anonymous faces he gets to know through the luxury high-rise's video surveillance system—and summons drinkable water from unlikely springs, as though by dowsing. Sustained (while supplies last) on high-end canned goods and top-shelf liquor, our castaway endeavors to escape, perplexingly, via a massive concrete light fixture on a very high ceiling. He uses the wreckage of costly canvasses and designer furnishings reduced to debris to build a platform reminiscent of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919-1920). He also constructs an altar, which he adorns with trophies—hardware taken painstakingly from the architectural chandelier—and paints a vaguely Masonic mural to frame it. By design, the film makes it difficult to gauge how long all this goes on for, placing viewers in a lockdown-y position sympathetic to Dafoe’s: calendars, the everyday trappings of linear time, have nothing on the eternal potential of leaving one’s artwork behind.

Speaking of the passage of time, I used most of my ten-minute slot on Inside press day to ask its star about Andrei Tarkovsky. I later read that Lars von Trier explicitly had Dafoe watch Tarkovsky’s 1975 The Mirrorto get in the mood before filming Antichrist, which makes sense. Dafoe, very warmly—and far less obviously—used the first few seconds of our Zoom to compliment the wall behind me.

WILLEM DAFOE: You got a good background.

VICTORIA CAMBLIN: Wow, thanks. What a great start.

WD: You win the prize today.

VC: I’m thrilled. I hope to win more over the course of our conversation. Jumping right in: what is your personal philosophy of time?

WD: Oh god, time is everything.

VC: There is a neon artwork by David Horvitz that appears at a very climactic moment in the film. It reads, "All the time that will come after this moment." What is Inside trying to tell us about time?

WD: Listen, it's all about being present. Performing is about being present. We shot this movie in chronological order. We were dealing with what was in the space. We weren't pointing to things outside. We weren’t anticipating scenes that were to be done. We weren’t [thinking about] scenes that had already happened. We’d go there every day, we'd enter this space, and we wouldn’t leave, basically, for 12 hours. I mean, we’d take a little lunch break. But time became bent. There was no light—there were [video] projections, but no natural light. Your sense of time, of where you are in the day, is totally scrambled. So being present and having a certain concentration on tasks was very important. So, if the phrase is—give it to me again?

VC: “All the time that will come after this moment.”

WD: Well, that’s the experience of the movie for me. When we were first approaching work on the script and finding out what things might be challenging or what might need to be changed, we had lots of discussions about how long Nemo was in that place. We couldn’t decide. We didn’t want to deal with wigs and beards and all that theatrical stuff. So we decided, “you know what? We don't know. We don’t need to know. All we know is the day that we start filming, I don’t cut my hair, I don’t shave.” I let myself go. And that was a very concrete measure of time because everything could be seen in the length of my hair, in the fatigue I was feeling, in the length of my beard.

VC: There’s a moment in the film when Nemo is pretty far gone already and enters this sort of dream state, where the woman he’s been watching through the video surveillance system comes into the room. It’s very Solaris. I assume you’re into Tarkovsky.

WD: Yes, of course. I adore Tarkovsky. In fact, I could play him with this mustache now.

VC: Absolutely. That’s perfect for this next question. Tarkovsky wrote a book called Sculpting in Time.

WD: I know it well.

VC: He writes that art must carry man’s craving for the ideal, must be an expression of his reaching out for it. And then later he says, “Art symbolizes the meaning of our existence.” Do you relate to any of this?

WD: That all sounds good. I mean, when I read Sculpting in Time, there are many things that turn me on, and some things are a little restrictive, because he’s this—he’s Russian. The movie raises a lot of questions about our relationship to art, and I think it’s fair to say that it expresses art’s power. In fact, I’d say [the power of] art and making art. Expressing himself is what helps Nemo survive. It’s maybe not clear exactly how things are resolved, but art is the thing that gives him a way of seeing hope, a thing to continue. He’s not burdened by all these obstacles he has. Some people watch the movie and say, “Wow, he melts down. He really goes crazy.” I prefer to think that he really just goes inside. He becomes more internal and reaches some sort of understanding that he didn’t have before. This is a perfect case of an obstacle being a gift. Even though he’s beaten up and he’s got lots of problems, in the end, he reaches a clarity that he never would’ve achieved if this didn’t happen to him.

VC: The cliché is often that art is what distinguishes humans from our otherwise animal nature, right? Painting the walls of the cave is how we are able to emerge from it, erect and knowledgeable, and aware. Your character goes a bit feral in the process of making all this art. Sometimes it’s hard to say if the creative impulse is part of his salvation or his undoing. Where are you at with that?

WD: When he starts to make art, that’s the thing that elevates him. Literally. When he starts drawing on the wall, when he makes that little altar, he’s making something that he leaves behind. It’s an expression of his time in that house. It’s an expression of who he is. That speaks to the function and the eternal nature of art. How long have we been drawing figures on cave walls? I mean, this is an impulse. This is a human impulse. Nemo’s hair may get long, he may get funky, but he becomes more human over the course of the movie, I think.

VC: You mentioned the altar, and I did want to ask about the theme of sacrifice. Are you thinking about sacrifice at all? It is a topic in a lot of your films.

WD: Exactly. But I don’t think of that altar in terms of sacrifice.

VC: Sacrifice is sort of in the air. Nemo is abandoned by his team when he gets trapped in the house, he kills a pet fish and the house plants for his own survival, but I think the real sacrificial stuff is happening with the art. The ritualistic destruction of the collections goes beyond survival. One talks about “sacrificing oneself for one’s art,” even, and one read of the film is that that’s what Nemo ultimately does.

WD: I'll jump a lot of Inside stuff and just say, you have to dedicate yourself to something. You’ve got to give yourself to something. That’s the only thing that gives life meaning. I’m interested in sacrifice. I don’t know whether I do it, but I know the times I’ve felt free, I’m not doing things for myself, I’m doing them for something else. I really believe that people who are truly egotistical and truly selfish—no matter who they are or what they have—are never happy people. They always have lots of problems, and they’re stressed. People who give what they have a greater chance of finding some kind of serenity and some kind of clarity in life.

VC: That would be a nice conclusion, but I’m going to try to squeeze one more thing in.

WD: Do it.

VC: And it’s going to be William Blake. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, which appears a lot in the film, Blake writes, “The road to excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” Do you agree? I was thinking of the idea of “excess” or “waste”—the excess of the decadent surroundings, and then of valuable possessions being somehow wasted—and what the film is saying about material value.

WD: I don’t know if it’s about waste so much as destruction. Nemo just becomes very in tune to the idea that you’ve got to destroy something to have something be born again. And that’s just a law of nature. We see it all around us. We try to forget about it because we like to think things only go up, up, up, up, up, up—I say this as I'm looking out at these huge skyscrapers. But it ain’t like that. It’s got to come down to go up. You’ve got to go down to come up.

VC: Did you personally destroy anything in the making of this film? Other than the set, of course.

WD: I banged myself up pretty good here and there.

Inside is directed by Vasilis Katsoupis, produced by Giorgos Karnavas, and written by Ben Hopkins. The film premiered in Berlin in February 2023 and hit theatres internationally this week. Its art collection, curated by Leonardo Bigazzi with production design by Thorsten Sabel, contains works by Egon Schiele, Maurizio Cattelan, John Armleder, Francesco Clemente, Adrian Paci, Masbedo, Petrit Halilaj, Álvaro Urbano, Maxwell Alexandre, David Horvitz, and Joanna Piotrowska.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

Related Content

DEAR JEAN-LUC GODARD

RICH THINGS: How Tourism, Sneakers, and Museums Make the Economy of Enrichment

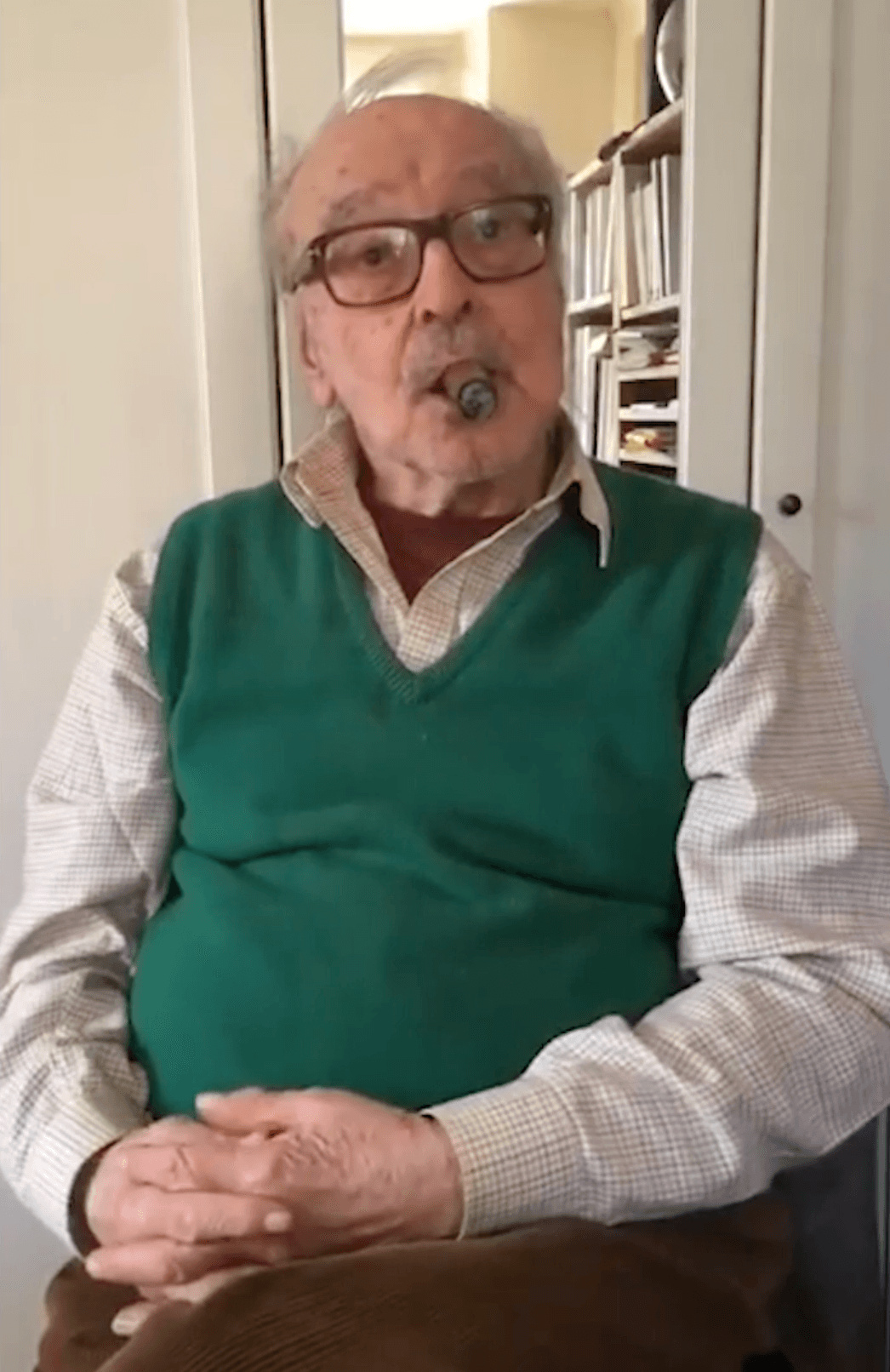

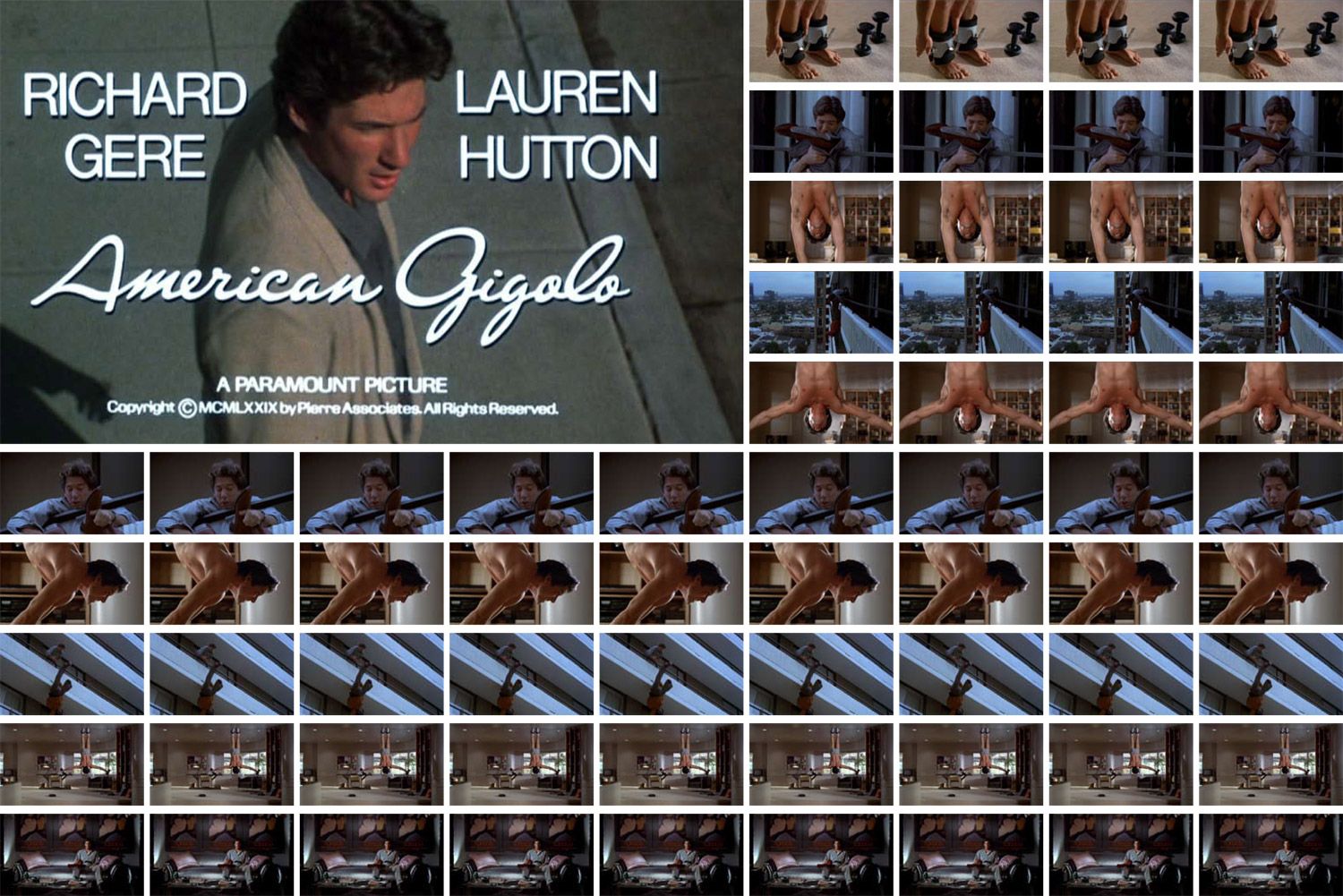

THE NEW ANGELES: GIORGIO MORODER on American Gigolo

On Power, Picasso, and American People: An Interview with FAITH RINGGOLD

“NEST.” Or, How PROZAC Spawned the Greatest Interiors Magazine, Ever.

LOVE! INSTAGRAM! COMPASSION! Between an Ipanema bikini and an over-decorated cake, FRANCESCO VEZZOLI's Love Stories

DAKIS JOANNOU: A Story of a Collector Told Through Four Works in His Collection