THE NEW ANGELES: GIORGIO MORODER on American Gigolo

This is the gayest non-gay movie ever made. This is a homo-hetero conspiracy. This is sex as aesthetics. This is color in place of emotion. This is surface and sound. We can still feel it today. We live in a world defined by it. American Gigolo. The year is 1980, and anything goes. Sex is free. Sex is without fear, though not for much longer: it is the year of Patient Number One, one year before the world learns of AIDS. Now is now. Who cares about tomorrow? The car, the body, Blondie — it all came together in a moment of magic.

Strange, then, that the men who made this movie didn’t match up at all: PAUL SCHRADER, the brooding, doubtful, megalomaniacal director; GIORGIO MORODER, the friendly, impulsively down-to-earth composer; and Ferdinando Scarfiotti, genius of color, of décor, of the sentiment in a building or a room. Scarfiotti was the aesthetic force behind American Gigolo; Moroder pushed it forward with his own, succinctly European beats, bringing a disco sensibility to an existential confusion. Schrader called these men his “axis-powers.”

Mr. Moroder, what car did you drive in 1980?

Giorgio Moroder: I drove a Mercedes SL.

Convertible?

Sure.

The one from American Gigolo?

A Mercedes SL 650, to be precise. I always drove Mercedes, it’s a good car. You can drive it with the top down, and I only needed two seats.

Air-conditioning?

I didn’t need it.

Which color?

Black, like in American Gigolo.

Do you remember what kind of suits you wore?

I know they were too gay, too European for the Americans. For them, it’s always a problem if somebody is dressed too elegantly, with too much color. That’s automatically gay.

Gay as in glamour?

No, no. My suits were blue – just a little more color here and there than you were used to seeing. I also wore a tie from time to time, and always a jacket. If you didn’t wear a T-shirt, you were automatically glamorous.

The clothes you wore on your album covers, did you also wear them on the street? These huge shirt collars? They were pretty racy.

That was all back in Europe. By the way, there is this commercial for Coca-Cola Zero and the movie Avatar, and in the very first scene, they show a poster with a picture on it of me from the 1970s.

All mustache and sunglasses. Did they contact you?

No. It looks as if they worked a bit on it. And the background is new.

Did you wear Armani like everybody did after American Gigolo?

The film made Armani in the U.S., that’s right. That was the moment it became a global brand – before that, he was just another Italian designer.

Thirty years later, Schrader is directing one dark movie after another, Moroder is making music for the Olympics – one after another – and Scarfiotti is long lost to AIDS, gone already in 1994. The Calvinist from Michigan, going through the eternal cycle of sin and redemption without any hope of Hollywood hailing the king; the workaholic from Südtirol, changing the way the world dances and listens and whatever else it does to music; the hedonist from Milan, who created a Los Angeles that never was.

What is the color of American Gigolo?

Paul Schrader: I can’t really say. I never think in these terms. I couldn’t say of any of my movies.

Is it true that Ferdinando Scarfiotti took a German Löwenbräu can as a pattern for the light-blue walls, the shirts, the objects? That’s why I remember the film as Löwenbräu bluish.

Yeah, that’s true – but there are other sets. Like the Polo lounge was all pink. Richard Gere walks into this big pink vagina. Well, he actually enters the Beverly Hills Hotel, but everybody knows what the Polo lounge looks like, and Nando [Scarfiotti] had to turn it into his own Polo lounge. [laughs] I will never forget Lauren Hutton’s yellow sweater in the record store. That was Nando. He had a lot of talent and power. I really deferred to him. They call a lot of people “production designers,” but he was it in the true sense of the term – which was originally used for Dick Sylbert on Chinatown, as a person who would oversee all elements of the visual.

Was Chinatown something you had to turn upside down, because it was this big, famous California-style, Los Angeles movie?

We were trying to figure out how to make Los Angeles look new. Chinatown came out of a noir tradition – you know, rainy streets at night – and we were looking for a more Roman or Tuscan feeling. The idea was to import people who saw it differently. Most important was Nando Scarfiotti. He had done some films with Bertolucci – The Conformist and Last Tango. He and Bernardo had just had a falling-out over Novecento. It was perfect timing. I went to Rome and convinced him to come. I had done two films before that, Blue Collar and Hardcore, neither one of which was really directed. I was simply illustrating those movies. But under Nando’s influence, I actually directed a film. I learned to think through a film visually. There’s a European sensibility in American Gigolo. We tried to see Los Angeles through their eyes, through Italian eyes. Of course, between the wars there were a number of films that saw Los Angeles through German eyes, but there weren’t any Italian style-driven films. For example, the opening scene was in a house in Malibu, and we were planning to shoot there on the first day. I kept saying, “Nando, where is that Malibu house?” There were like 30 houses stacked up on the beach, but he went, “No, no, no.” One day he came into my office and said, “I found the house, let’s go.” So we went to Malibu and he said it had just been constructed: “Ignore the inside, I will build a flat with all kinds of bricks and stained glass, but the scene where the two are talking, that should be on the porch, out on the beach.” They had just sunk these huge concrete pylons, where the cardboard moldings had just been taken off. Nando said, “If you shoot this scene in the afternoon, the sun will be right between the two pylons and if you do it all in one shot – or steady cam quite quickly – you won’t have continuity problems because of the descending sun.” And I was looking at the location and realized it was an arcade in Milan. Nando found an arcade on the beach. He was home.

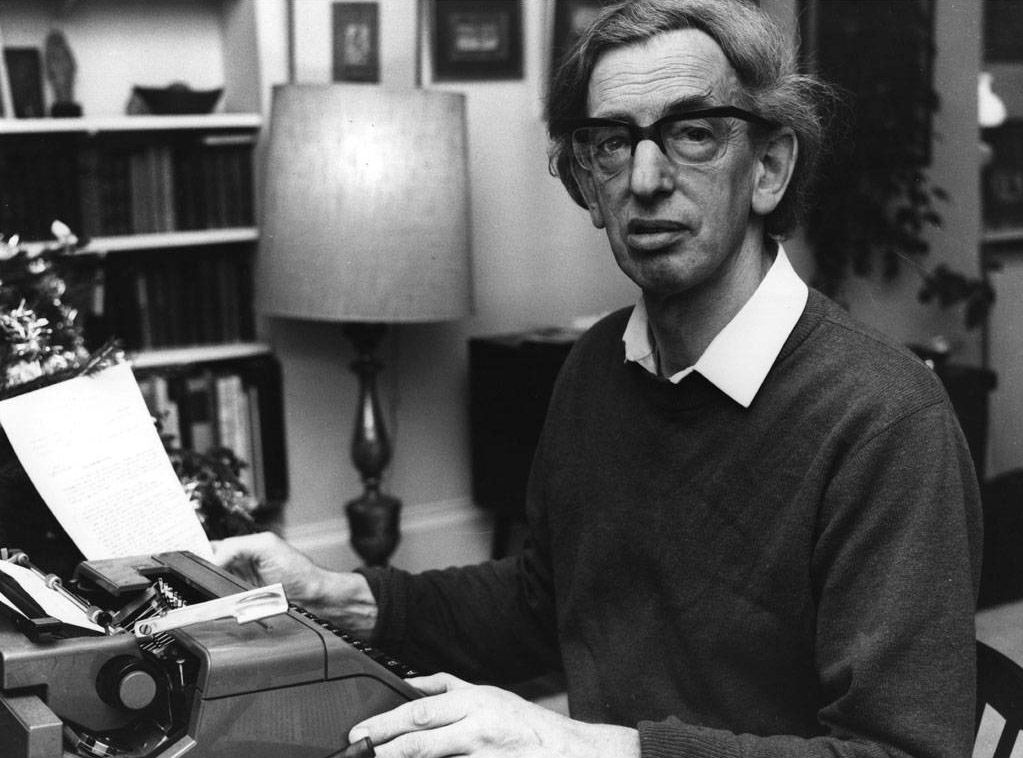

Schrader is perched on a chair in a room of the Chelsea Hotel in New York. Is he ever at ease? In 1970, he had to decide between continuing to be a film critic and becoming a scriptwriter. his writing on film had already included some serious work on Budd Boetticher, on film noir, and in praise of Charles and Ray Eames’s films. And Schrader was the only one who would slam Easy Rider. The Transcendental Style in Film, his book on Yasujiro Ozu, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and Robert Bresson, was published in 1972, and his mentor at the time was the grande dame of film criticism, Pauline Kael, who never really forgave him for having finally chosen a Hollywood career. That same year, Schrader wrote Taxi Driver in just ten days. All chronicles of that time, like Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, describe him as the nerdiest of nerds: “short, with greasy black hair, a broad, fleshy nose, and geeky, Groucho Marx glasses, he carried all his childhood frailties with him into young adulthood. he suffered from nervous tics, ulcers, and asthma. A speech impediment made him mumble self-consciously, eyes cast down, staring at his feet. He was even claustrophobic.” But he was also the most brazen of hustlers.Does it have to do with your religious background that Gigolo develops from a car commercial into something more of a “transcendental style”?

Paul Schrader: I’ve always felt a little uneasy about the transcendental style. I think it is more a car commercial. It’s a film about surfaces, about a man who lives on the surface, who can’t look into himself, who takes cocaine in order to get dressed. It’s the kind of film where a wrinkle in a shirt requires you to do another take. That wrinkle in the shirt is the same thing as a fluff in the dialogue. That’s how surface-driven it was. Then I had this perverse idea of just taking the ending of Pickpocket and slapping it on this very superficial film.

I like the spiritual essence coming from nowhere.

In retrospect, I think it is more perverse than our authentic interests, than anything integral.

It’s grace. Something from nothing transcends.

I don’t know, it’s just the ending it shouldn’t have.

You regret it?

I probably would do it differently now.

How?

It wouldn’t be as commercial.

In the beginning?

At the end. It would be much darker.

The script for The Yakuza has some of the best lines ever written in Hollywood, and among them is one that could stand for Schrader’s entire œuvre: “When an American cracks up, he opens up the window and shoots up a bunch of strangers. When a Japanese cracks up, he closes the window and kills himself.” All of Schrader’s films seem to be about this ying and yang, about homicide and suicide. When talking about Mishima, in which the window is closed, Schrader says that suicide has “a lot to do with the artistic impulse to transform the world” – BAM! His brother Leonard, with whom he wrote The Yakuza, adds, “This is what we grew up with. We had Dutch Calvinism, which an expert told me is a permanent form of mild depression, just nudging us toward suicide, and then we had to keep this secret from everybody, that my dad’s only relatives were blowing their brains out all the time.”

What happened to you between Taxi Driver, which you wrote in 1972, and Gigolo?

Paul Schrader: I wrote Taxi Driver as personal therapy. Still today, I see screenwriting as a way to address any number of personal problems that are running through your life. At the time I wrote Gigolo, I was in psychotherapy, and I was also teaching a course at UCLA. One of my issues in psychotherapy was the inability to express my feelings. When you have a problem – like loneliness in Taxi Driver – you are looking for a metaphor. The metaphor for loneliness is the taxicab. Beautiful! And in my class at UCLA, we talked about somebody’s script. And I said, “what does this guy do? Is he a businessman? A salesman? Is he a teacher? Or is he a gigolo? Boom! Gigolo – I said the word. That’s it! A metaphor for a man who cannot express his feelings. Perfect metaphor! The wires touched. So it wasn’t meant as a commentary of the times. I would just work through something that was bothering me.

Would you say the taxi driver and the gigolo come from the same point?

Well –

Same problem?

No. The taxi driver’s problem was loneliness. The gigolo’s is the inability to express his feelings, to express love. It’s a character I returned to again and again. Travis Bickle, Julian Kay, John latour in Light Sleeper, and Carter Page III in The Walker.7 At 20, 30, 40, and at the age of 50. It’s a very similar character. These characters are not so much people as souls. They drift around and things happen to them. They watch and are acted upon. As I get older, my views about this character change.

Is Taxi Driver the image of America that people didn’t want to see anymore, and American Gigolo the image that supersedes it?

You can say that in retrospect. I think authors who try to speak to their time usually fail. The author who most effectively speaks to his time is actually speaking to himself. He just happens to live in that exact moment. Tennessee Williams wasn’t trying to say something about the 1950s. He was in it. He defined it. Then the time went away and his talent went away. But I don’t think for a second to define my times. I don’t think this is how it works.

Moroder was always Mr. Disco, never Mr. Zeitgeist. He’s won three Oscars: Best Original score for Midnight Express in 1978 and Best song for both “Flashdance … what a Feeling” in 1983, and “Take My Breath Away” for Top Gun in 1986. He has three Grammys. He made Donna Summer with “I Feel love” in 1977; He made Munich with the Musicland studios and Munich Machine. He became an icon of his time with his mighty mustache and ferocious sunglasses, a face that became a logo. When we meet, he wears an eggplant-colored down jacket, as if we were après-ski in Gstaad. But this is the coldest day in Los Angeles in years, and it’s raining as we sit down at the Palihouse Holloway in West Hollywood, one of those new boutique hotels made for people who need to be a part of the Zeitgeist. Moroder looks out of place among the skinny boys and girls. He may be at once the most underrated and overrated music producer of his time. But he’s back: Quentin Tarantino just used “Putting out the Fire” – Moroder’s 1982 collaboration with David Bowie on Cat People – for Inglourious Basterds, and Sofia Coppola wants to work with him for her new movie.Did you have a certain sound in mind?

Giorgio Moroder: No. I think Schrader wanted something like Midnight Express.

But there is this American Gigolo sound.

The only thing I really like is the song.

“Call Me.”

Blondie. The score is very typical, synthesizer and all these things that you’re tired of hearing today.

No!

The problem was that, after the Oscar for Midnight Express, a lot of movies had this synth sound. Synthesizers were cheaper than a whole orchestra. Maybe it was my mistake to keep that sound for too long.

This cool, technical sound.

And very few different sounds. In the end, it was always a similar sound.

Did you use samples?

No, this was purely electronic music. The first samples were used in 1984 or 1985.

So the synth modulated the sounds that were already there?

Exactly.

You worked mainly with Rolands?

Mainly the Roland JP-8 series.

Was it difficult to work with only one sound?

There were thousands of sounds. But you love only one, and you work with that.

How did you come up with the Munich sound? Disco?

It all started with the big Moog. On Midnight Express, I had somebody who created this sound for me. It was rather exaggerated, with noises and effects. On American Gigolo, I already had the Roland with a lot more sounds. It was much more pleasant, with violins and piano.

But the main difference between you and other electronic musicians, like Kraftwerk, was that you used the disco beat.

The first song that used synth for a dance track was in 1977 – “I Feel love” by Donna Summer.

Did you know Kraftwerk?

Of course.

But there was no exchange, no contact?

No.

And other bands?

These three guys. What was their name again?

Can?

No. Tangerine Dream.

But they were hippies!

But they were also very modern. They had the hottest rhythm of all. Kraftwerk only had tschak boom tschak.

There is even a song called “Boing Boom Tschak.”

Jean-Michel Jarre also had a very nice rhythm. Not really pushing forward though. Tangerine Dream had a certain drive.

How did you find your sound?

I had come up with disco a lot earlier in Donna Summer’s “Love to Love You Baby.” There was the beat, but no synth. I had used synthesizers in 1972 for my hit “son of My Father.” But the people didn’t really seem to like it – too many people used it to create weird sounds. Spheric, hippie style. The “Moroder sound” was pushing forward, aggressive, driven. I wanted to use synth for songs that were set in the future. The cold, mechanical beat of the future. American Gigolo was not that cold. I used the synthesizer more like an instrument.

And how did you decide to work with Blondie?

Blondie was big. She was number one. You look for the best singer, and she had this great image, absolutely hip, absolutely cool.

You sat down with Schrader and Scarfiotti and talked about what is cool?

It was not very philosophical. I sent her a demo tape, she liked it and made the lyrics. We recorded the song. And we didn’t time the song to the movie, we had the tempo that we wanted.

The opening scene existed already?

Yes. Some directors use their own music when they cut the movie, on “tip tracks.” But Schrader didn’t. And he didn’t change anything either.

The black SL, the road, the light, Richard Gere with sunglasses. Like a car commercial. California, driving, the sun, rock music … and Debbie [harry] found some really good lyrics. But Blondie wasn’t disco. She was more New Wave. After Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” she had her first real disco hit, “Heart of Glass.” De de deee de de de deeeee. Not dudddelduddddelduddddel.

Which is what?

The first one is Donna Summer: de de deee de de de deeeee. The second is New wave Blondie: dudddelduddddelduddddel. “Heart of Glass” was her second biggest hit, absolutely disco.

So, yes, those were strange years. Scarfiotti had just made the only Communist Hollywood production ever with Bernardo Bertolucci: 1900. Those were pre-AIDS years, pre-Reagan, pre-Yoga. And there we have Julian Kay, the esoteric prostitute caught up in a complot of politicians and pimps, saved in the end by an almost religious kind of grace. The message was clear: something was about to change; something was about to happen.

Did you feel the change that was about to happen? You even partially caused it.

Paul Schrader: To an extent. I remember running into Richard Gere a while later, and he said that I had told him back then that we were in for kind of a Neo-Edwardianism in men’s fashion. After the 1960s and 70s, cool classicism was in for a comeback – and this is how I wanted to dress this character. Richard said he hadn’t believed me, but that I had been absolutely right. I know the kind of lineage of Gigolo. It was very Warholian – ironically, we are in the Chelsea Hotel. Interview Magazine championed it. Andy loved it, and once Andy started talking about it, it became kind of a Studio 54 film, that whole crowd. It was the magazine that set the trend in motion.

Gigolo was a very gay film.

Nando was gay, and the whole environment was. He was a count, a very charismatic man who tended to draw people to him. He had a house on Melrose Drive, and on weekends, people would go there. It was predominantly gay. It was my world at the time. This was just before AIDs. It was also at Nando’s house where he was trying to tell me about this thing they were calling “gay cancer.” I just said, “what are you, fuckin’ crazy? There is no such thing as gay cancer.” That was the first time I heard of it. It was a matter of two or three years that everybody knew, and I lost many friends – Nando Scarfiotti, among others. Half of the people I knew. It put an end to a kind of cultural moment.

What fascinated you about this moment?

Well, I come from a religious background. I was a very conservative kid who was liberated in the 1960s by coming out here and getting involved in radical politics. But I was still rather shy when it came to women. I wasn’t gay, but I was shy. It occurred to me that women kind of wanted the same thing that gay men wanted, which was just somebody to talk to, somebody to hold, somebody nice, somebody to be around. I learned the conflicts of dealing with women by dealing with gay men, because I knew in the end nothing would happen. I mean, you were dancing all night long, you stripped to the waist, you swayed, and in the bathroom, you did cocaine. But in the end, it was just a walk on the wild side. Nothing would happen. But I was driven into it because it drove away my inhibitions. I wanted to break into the world of human contact, with women. I was just too inhibited by my upbringing, and this was so outside that. I’d come in through the front door and somebody would say, “You know, there is a back door.” And I’d say, “Yeah, this is cool.”

Richard Gere has this special walk in American Gigolo.

That was the whole idea. I had a tough year before Gigolo. I was working for Warren Beatty, but that film never happened, like most projects with Warren. And then there was the Warren sensibility: “I just walked into this room. This room is now a better place than it was ten seconds ago because I entered it.” This kind of grandiose confidence.

You developed a this-room-is-now-a-better-place walk?

You have to walk on the balls of your feet, keeping the weight off your heels, that kind of John Wayne thing. It’s the Richard Gere walk. He still does it. Does he? [Schrader pretends to not have seen a Richard Gere movie since Gigolo.] I told Richard, “You know, all great stars have a pansexual appeal.” Parker Tyler had pointed that out. The women know how to play the women, the men know how to play the men. And I said to Richard, “look at the great stars. They’re not ignorant of their homosexual appeal. John wayne wasn’t ignorant of that kind of walk he is doing, that prancy-Nancy walk he does. Like he was holding something up his ass. He’s no fool. He knows what he’s doing. Look at Cary Grant, look at these guys. Even the straight ones.”

Things changed for Schrader in the 1980s. After three masterpieces – American Gigolo, Cat People, and Mishima – he was forced out of the studio system and became an “independent” against his will. To this day, he continues to make low-budget, dark, and often dangerous pictures, with one exception: In 2003, he found himself again on the set of the $40 million Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist, a subversive film emphasizing spiritual agony over horror/ecstasy. In the final shot of John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), a film that heavily influenced Schrader, John Wayne says with self-damning angst: “The price of vengeance is that you have no home.” All of Schrader’s films are infused with metaphor and doubt; each one conceals other films beneath its surface.

Where does Julian Kay’s name come from?

Paul Schrader: I think I should have gotten a better name. The Julian is from Stendhal’s The Red and the Black and [with a deep voice] Kay is from Kafka’s character from The Trial, Joseph K. [laughs]

He’s doing drugs.

Those were the harmless years. I didn’t know anybody in 1979 who had a drug problem. Scorsese was the first person, and that started on New York, New York. Two years later, almost everybody had problems.

In Gigolo, it’s still very casual.

I thought it was kind of cool to take a line to get dressed. [laughs]

It’s cool because it’s not commented.

That’s how it was at the time. It wouldn’t be commented. I don’t think anybody at the studio said anything. [laughs]

Is this what defined the time?

Sure. Cocaine was huge. It was a drug-built system. At the time, everybody had the illusion that it wasn’t like heroin addiction. But it was, psychologically – it wasn’t chemically addictive. You would go to major parties, Sue Mengers kind of parties – the most important agent at that time – and there would be cocaine on the table. So it wasn’t a stigmatized environment. There was a restaurant up on sunset strip. All of the tables had mirror tops and curtains you could close. It was the right time to do good cocaine.

And you left a line as a tip for the waitress?

No, I didn’t do that. I was never that generous. [laughs] I remember exactly the moment it all ended. In 1982, I was in a meeting at Universal about the ad campaign of Cat People, and somebody walked into the room and said, “Did you just hear?” “Hear what?” “John [Belushi] OD’ed. He died in the Chateau.” I immediately knew it was over. Anybody who tells you the first two years are bad is lying. The first two years are great, then maybe the next year or two. But by the fourth and fifth year, you start to have problems. I was starting to have problems, and then I heard that John died and I said, “Ja, it’s over. It-is-over!”

Interview by GEORG DIEZ and CHRISTOPHER ROTH

Credits

- Interview: GEORG DIEZ and CHRISTOPHER ROTH