DAKIS JOANNOU: A Story of a Collector Told Through Four Works in His Collection

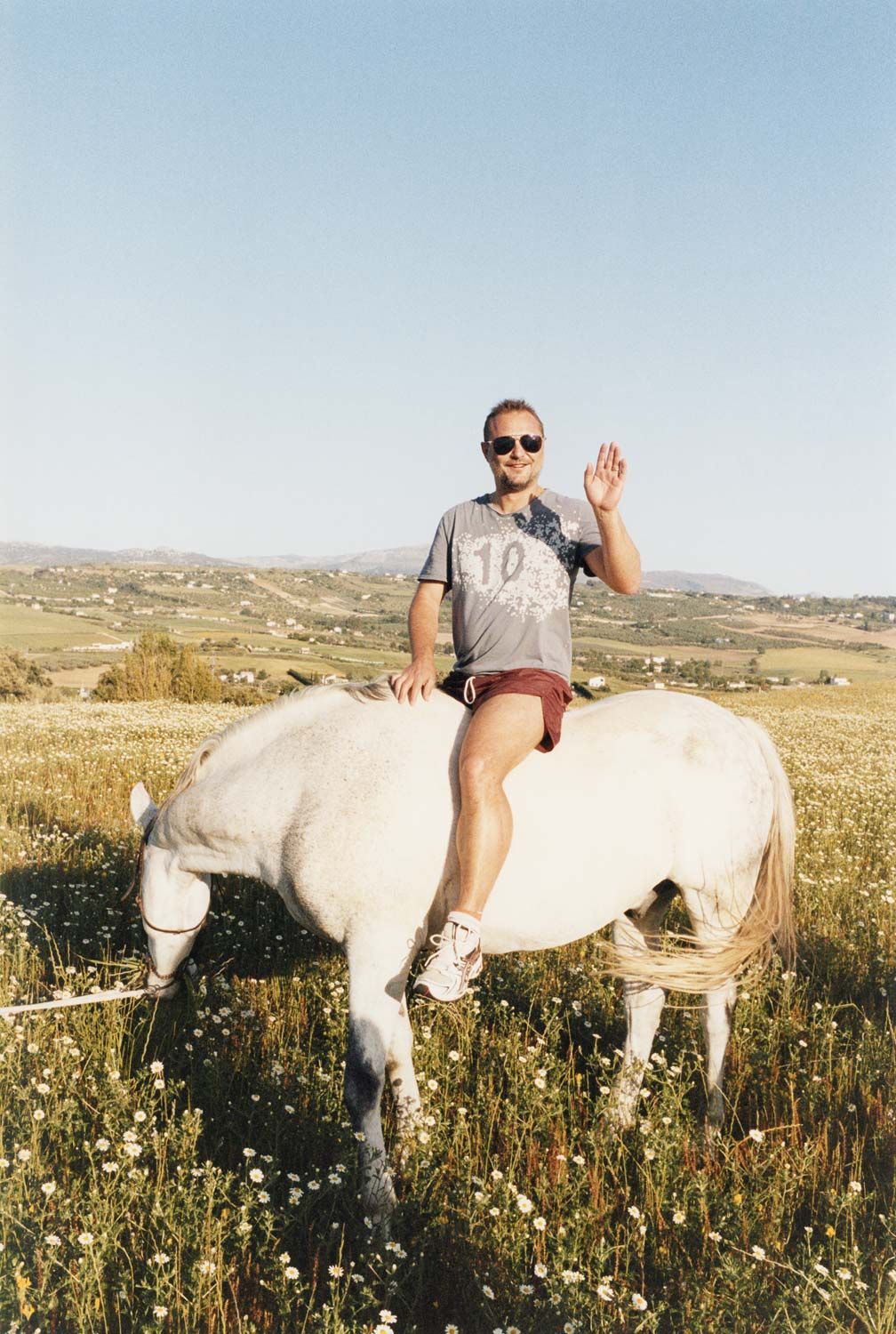

At the apex of Greece’s financial crisis, 032c’s Thom Bettridge travelled to Athens and Hydra to visit Dakis Joannou, an industrialist and hotel magnate famed for his contemporary art collection.

Much like his yacht Guilty, Joannou is a surreal, unapologetic, and larger-than-life figure. In a turbulent year of capital controls and austerity sanctions, Joannou’s endeavor proved to exist in its own sovereign universe. During 2015, his DESTE Art Foundation hosted more exhibitions than any other in its history. Joannou’s collection tells the story of a 50-year-long infatuation with art that has spun out into a network of objects and friendships. “It’s about changing ideas,” the collector says regarding the public impact of his work. While he has been credited with pulling the art world’s attention to Athens, Joannou insists that the social benefit of his foundation is “collateral.” But what larger project – or desire – this benefit is collateral of remains a mystery.

Paul Chan, Hippias Minor, 2015

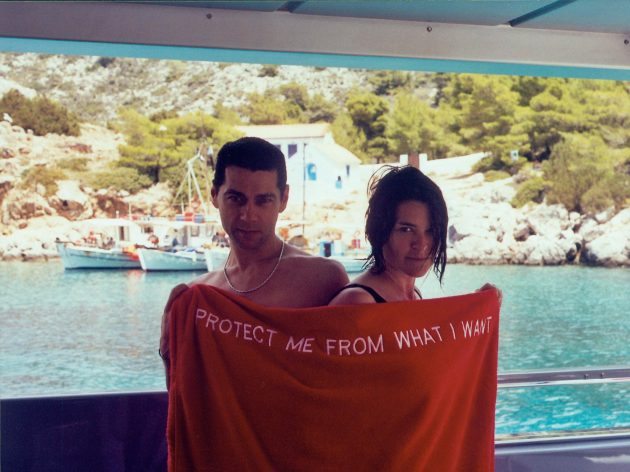

“If a visitor knows he’s going to be lied to, then he is forced to challenge the authority of what he sees,” the docent said. The sun was beginning to turn pink as a small group of us sat on a concrete porch on the Isle of Hydra. We were discussing Hippias Minor, an early dialogue by Plato with a controversial thesis. At this point in his work, Plato’s Socrates played the role of provocateur, publically trolling the Athenian establishment with counter-intuitive, yet rational, arguments. In his conversation with the celebrated sophist Hippias, Socrates defends the excellence of Homer’s Odysseus – the inventor of the Trojan Horse – who Hippias claims is inferior to other heroes on account of his dishonest ways. In the process of dismantling Hippias, Socrates argues that someone who deceives cunningly and willingly is superior to those who tell the truth. Lying is a skill, and it requires a special trait: the ability to create another reality.

Our discussion of cunning quickly shifted to more recent Trojan Horses in Greek history: corruption surrounding the 2004 Olympic Games, un-taxed swimming pools and Porsche SUVs, defective Siemens submarines, and the upcoming election held to address Greece’s ongoing economic meltdown. It was September 2015, and bigots in the Anglo-European media had spent the entire summer painting Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras as an overwhelmed buffoon. But maybe that was the perfect way to appear in front of debt collectors who are asking for hundreds of billions of dollars?

“I think us Greeks have a special appreciation for cunning,” a journalist said on the porch, who told me she had recently switched to travel writing due to declining Greek newspaper budgets, “I mean, look at that boat over there.” She pointed to the mouth of Hydra’s harbor, where a motor yacht painted with a Jeff Koons razzle-dazzle camouflage pattern was docked in the distance. “That boat’s named Guilty,” she smiled, “If you say it first, what can anyone accuse you of?”

The boat she was pointing to belonged to Dakis Joannou, who also owned the building in which we were sitting. Furthermore, his art foundation DESTE had sponsored Paul Chan’s commission to create the translation of Hippias Minor that we had all been browsing. The boat omitted the sensation that we were all sitting in someone else’s planned reality. Earlier that morning, Guilty pulled into Hydra and parked itself near a seaside restaurant formerly known as Lagoudera, where Aristotle Onassis had once presided over a revolving cast of 1960s jet-set celebrities. From the moment of its -arrival, the yacht became required viewing for a town that curls like an amphitheater around its harbor. Or perhaps it was the billionaire who was watching all of us, an invisible lunch guest chewing salad behind the tinted windows of his Pop Art battleship.

THOM BETTRIDGE: Tell me about the birth of Guilty.

DAKIS JOANNOU: With the architecture of the boat, we wanted to forget about style altogether. We wanted to put these spaces next to each other – living room, kitchen, whatever. Then we trimmed it a bit and ended up with the shape. I showed it to Jeff Koons when he was in Corfu and asked him what color it should all be. He came up with the idea of dazzle camouflage. I thought it was a great idea. Then I saw Ivana Porfiri. I tell her, “Jeff gave me a great idea about painting the boat.” She opens her file and she has the exact same idea! Two people came up with the same idea completely independently. I just had to do it!

What about the name?

I couldn’t decide on a name for a long time. Then I saw a Sarah Morris painting coming up for auction called Guilty. And I said, “We’ve got it!” I bought the painting, and Sarah also came to paint the word “Guilty” in the main guest room – like her painting, but more enlarged.

In this time of economic crisis, negative attitudes have been developing about wealth. Does the name of the ship address that as well?

It’s just an idea. It’s a boat painted like this – so what? Why should it be luxurious, or offensive? It’s just a yacht. It’s not a mega-yacht. It’s like a tenth of some of the other boats around. So it’s not about showing off. It’s just a simple boat with living rooms and bedrooms. That’s it.

When it was developed in World War I, razzle-dazzle camouflage was designed so that you couldn’t see what direction a boat was moving in. You couldn’t hit it, because it was impossible to triangulate where the torpedo should be shot.

That happens with our boat. When it goes slow, people from far away can’t tell if we’re coming or going.

It’s also a metaphor. At the Paul Chan show, I spoke with a group of people about cunning in Hippias Minor. Tricksters and Trojan Horses. Greece is in a crisis, and Guilty is a way of being completely in your face while making a joke about itself at the same time. It’s a moving target.

We can take it a little too far. I bought a work by David Shrigley – it’s a big flag that says “Please don’t kill us.” I put it up on Guilty, and when we were in Hydra, people were asking about the flag and saying it looked great. Then we went to Rhodes, and the islands near Turkey, and the -police came and called the captain. They said, “It’s your business if you want to keep it up.” And we said, “But please don’t kill us!” [Laughs]

Documented in numerous articles, Joannou’s yacht Guilty has become a living-breathing meme of art world excess. It is the crown jewel of a super-charged cultural milieu, one in which auction results continue to balloon towards billion-dollar figures and Instagram provides art fairs with mainstream appeal. This context has been influenced greatly by Joannou and the “blue-chip” artists – such as Jeff Koons, Urs Fischer, and Maurizio Cattelan – that he has collected and befriended. Guilty is stuffed with the prizes of this conquest. However, it would be reductive to call it a trophy. Joannou’s yacht is one of many episodes in a longstanding love affair with objects – one that is personal and libidinal, yet deeply public. For the collector, the boat seems like the fulfillment of a Citizen Kane-esque goal: to live inside a work of art. Such a proposition is alienating to those of us without a private jet, and yet Joannou’s endeavor is strangely familiar in a world defined by the high-speed consumption of culture. Before smartphones, it took an enormous bankroll to freely collide disparate objects and images, as Joannou did in the early exhibitions of his DESTE Foundation in the 1980s and 90s, which mixed ancient Cypriot pottery, Neo Geo painting, American advertisements, and a whole host of contemporary artworks. The hyper-consumption that was once an old world privilege is now a digital norm. And Dakis Joannou has become the moneyed ancestor of this moment. He is the Internet’s grandfather.

Jeff Koons, One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank, 1985

In 1964, Dakis Joannou glued a Dunhill pipe to a Coca-Cola bottle and painted it white. He was living in Rome at the time, and had just received his first painting – a piece by Lucio del Pezzo with a Jasper-Johns-like painted target – as a gift from his parents for having graduated architecture school. The homemade sculpture was Joannou’s last work as an artist, but it innocently predicated the spirit of things to come. The Cypriot mogul now owns one of the world’s most influential collections of contemporary art, as well as the rights to distribute Coca-Cola in several countries. Magritte’s pipe glued to Warhol’s Coke bottle, all cast in the mode of Duchamp. This is Joannou’s holy trinity: Surrealism, Pop, and the Readymade.

The artwork you made when you were young, of a pipe glued to a bottle – what significance did it have to you when you made it?

This was at a time when I had just moved from New York to Italy in the mid-60s. New York at the time was at the height of Pop Art. As a student, I wasn’t really in art circles, but I was going around seeing shows and absorbing all of that. Then I went to Rome. I was already interested in art. Duchamp has been for me … a god. So having this pop experience in New York City as a student, I then moved to Italy and was faced with a completely different environment. I didn’t really have a relationship with Arte Povera, which was emerging at the time. So it was really between the -metaphysical and the pop, with Duchamp always on my mind. I then got the idea of making this gesture, which became an object that contained all these elements of where my mind was about art.

It was not until almost 20 years later – over lunch in Athens with the critic and curator Pierre Restany – that Joannou’s interest in art collection would become something more than a hobby. After Restany suggested he start a foundation, Joannou met curator Adelina von Fürstenberg during a business trip to Geneva, who introduced him to a cast of international artists such as Joseph Kosuth and Marina Abramovic. With the help of Von Fürstenberg and others, Joannou started DESTE, the art foundation that became the gravitational center of his acquisitions. From its very onset, DESTE positioned itself as a project that combined the visibility of a public institution with the reckless abandon of a private endeavor. Its first exhibition, “Emerging Images,” took place at his family’s newly constructed Athens InterContinental Hotel. In what would later become classic Joannou form, the exhibition simultaneously worshiped and mocked its gaudy setting. In a description of the show, the collector longingly recalls a large-scale installation made of apples by Leda Papaconstantinou that rotted after two weeks and created an odor that turned off hotel guests. But DESTE’s international reputation and signature brand of full-frontal visual representation was forged under the stewardship of Jeffrey Deitch. Deitch and Joannou met in 1984, while Deitch was working as an art adviser for Citibank in Geneva. The partnership seemed meant to be from the beginning. During their very first outing in New York, they found the piece that would come to define the Cypriot’s collection. Thirty years later, I spoke to all three men involved in this encounter.

Tell me about how your work with Dakis Joannou began.

JEFFREY DEITCH: I was introduced to Dakis as someone who wanted to develop a museum on contemporary culture. After our initial meeting in Europe, we met in New York and I took him to some downtown galleries. It ended with us visiting the first Jeff Koons show at International With Monument. Dakis was so struck by Jeff’s work, and One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank was his first purchase in this new collection.

What struck him about the piece?

One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank is a very, very strong work. Years later, it is still very strong and compelling. It also led to so many things. Look at Damien Hirst, for example, or other younger artists that are working with aquarium formats. It’s a strong formal and conceptual work. There’s so much there – the connection of putting together geometric and organic traditions in art. In addition to that, it’s an intriguing commentary on contemporary visual culture. After all, it is a basketball floating in the tank – one of contemporary culture’s central obsessions. It remains central to Dakis’s whole approach to collecting and led to a great friendship with Jeff Koons.

How did you meet Dakis Joannou?

JEFF KOONS: I met Dakis in 1985. It was through my “Equilibrium” show at International With Monument in the East Village. It was the first time Dakis went around with Jeffrey Deitch. Jeffrey was with Citibank, and he was in contact with Dakis for a while, but it was the first time that they went out together and looked at art. Dakis was really moved by the exhibition and he acquired the Equilibrium Tank.

Jeffrey Deitch told me that the tank remains central to the Joannou collection. How would you define the spirit of this collection?

Dakis is drawn to things that stir curiosity – things that are on the edges of normal perception, things that help break down rules and dogma. Dakis is intellectually curious. But when you’re curious, it’s not about art. Art is a vehicle. But it’s how it can stimulate and create its own set of possibilities for yourself. I think that was when Dakis got re-interested in art – there was a period when he got curious about art and then he left that and he wasn’t so profoundly involved. And then, when he saw the exhibition in 1985, it re–triggered his interest in contemporary art. He then became involved in it on an international level. I think Dakis was looking to – within himself – stimulate his curiosity about life. He was very involved in business and he was managing his family life while travelling the world and building the company. And there was a certain point where he realized that he had to enjoy this experience. He let art be the vehicle to let him really look around and enjoy the experience of life.

Are there any particular things or impressions you remember him telling you when he first saw One Ball Equilibrium Tank?

He was excited and he really enjoyed it. He enjoyed the maintenance of the piece. Dakis had a gentleman that worked for him named George, who was very, very knowledgeable about how to continue the maintenance of the work, and he put great care into it. So whenever I would see an image of the Equilibrium Tank, it was always very, very fresh. And he would always keep it that way, year in and year out. In every aspect, collecting is a way of life. It’s a celebration of the enjoyment of becoming. We live in our interior life and in the exterior world. This dialogue back and forth is constant in Dakis and his collection. You seek clear reference to psychological things taking place, but it is also very, very externalized. So you have the world – its effect on the mind and the body – and then you have the effect of the mind and body onto the world.

I think there’s a similarity between many of his ambitions as a collector and the ideas in your work. It seems as though he’s very drawn to these large, iconic images. There seems to be a lot of object-desire in the things he chooses to surround himself with – a lust for things.

I think Dakis likes a Gestalt, a very strong sensation when you see something. He likes the senses and the use of feelings. Feelings become ideas. Ideas come about through sense-perception. And as soon as you explore ideas, you want to come back and connect that to the body again. There’s this dialogue with the body that’s also in classical Greek art. It’s all about the harmony of the body and the mind. Dakis never gets away from the body completely. He always remembers the body and the functions of the body – the needs and desires of the body. But at the same time, he’s able to dwell in ideas that are completely abstract – that are ideas for idea’s sake. Yet neither of them ever completely leave the other. They are polarities, but they always find a sense of harmony within the whole collection. And that’s just a classic Greek ideal.

What were your impressions when you first saw One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank? How long did it take to realize that this would be the seminal piece that began your collection?

DAKIS JOANNOU: It took a second. Not to figure it out, but to connect with it. It was a kind of a perfect object – so simple and normal – but then totally abnormal, because the ball is not in a normal position. It’s impossible to have a ball stand in the middle of water. You see a perfect object in an ideal situation and you suddenly realize that there’s something wrong with it. This clash was exciting for me. That’s why I wanted to meet Jeff and talk about it. And then I bought it afterwards. [Laughs]

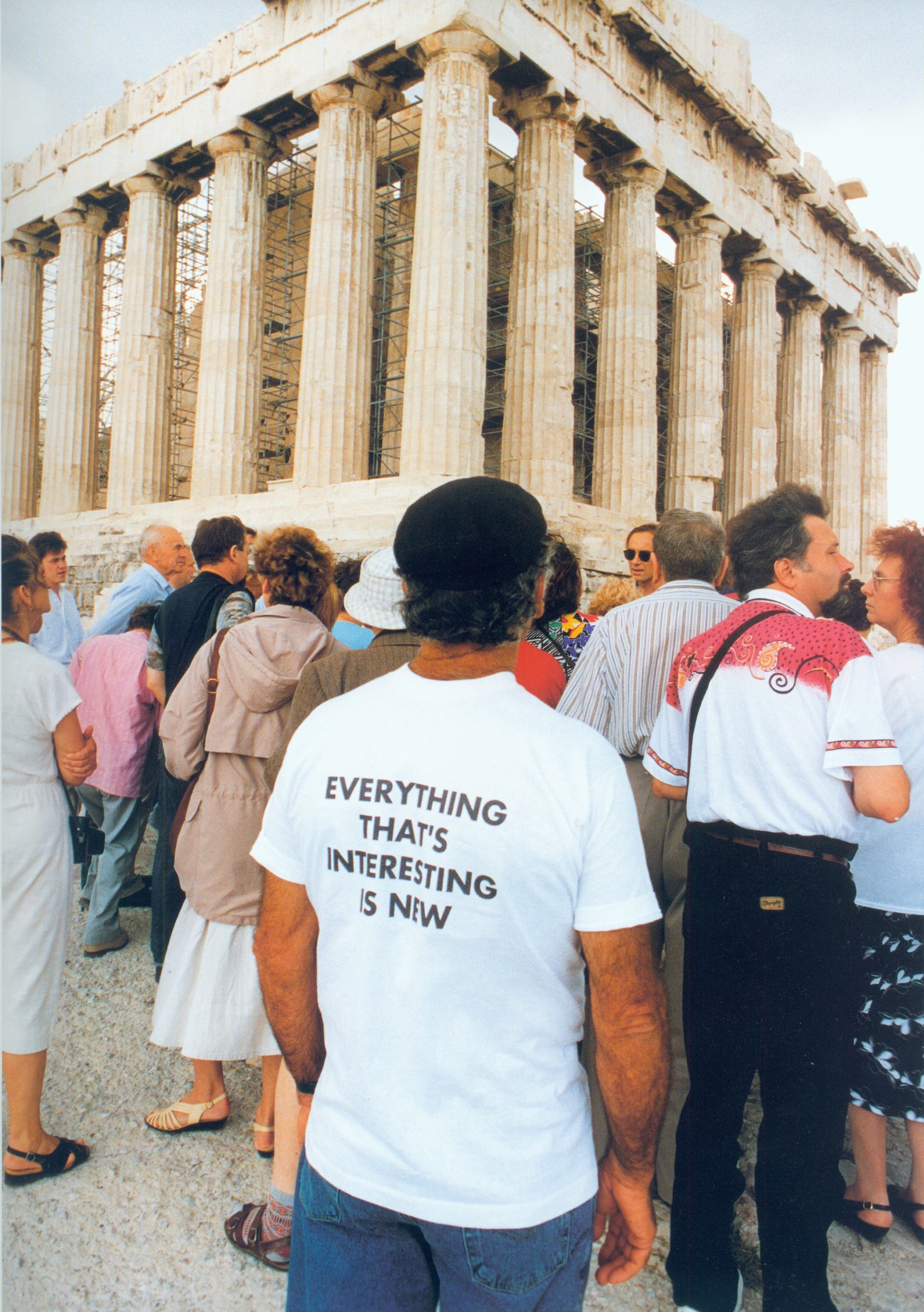

In the years that followed, Joannou and Deitch would unravel the power of this sculpture – this “perfect object” – into a zeitgeist-shaping pile of acquisitions. At the House of Cyprus in Athens, the duo put together a series of four exhibitions on bombastic topics: “Cultural Geo-metry” (conceptualism and commerce), “Psychological Abstraction” (surrealism and telecommunications), “Artificial Nature” (advertising and ecology), and “Post-Human” (technology and identity). At its core, these exhibitions revolved around a strange sense of humor that focused on exuberant breaches in the art-life continuum – a version of Fluxus with an American Express card. Dan Friedman’s cover for the “Cultural Geometry” catalogue was a magazine clipping of a Midwestern family arranged in an absurd formation of mass-produced vehicles. Such gestures felt at home teetering on the edge between satire and decadence. As Paul Taylor wrote in a review of “Cultural Geometry” in Flash Art: “The exhibition reeked, rather enjoyably, of collusion … All in all, the exhibition was set to be a fascinating meeting of minds from the most venerated institutions of the modern world: financiers, corporate designers and advisors, art collectors and, of course, artists too.”

The Joannou-Deitch partnership was intellectually concerned with the condition of the modern consumer yet completely gripped by its own consumption on an epic level. The result of this powerful irony-machine was an international shopping spree that inhaled a decade of cultural production and digested it into an idea of the “contemporary” that is now ubiquitous in the museums and hotel lobbies of the world. The frenzied appetite of this endeavor can still be felt while looking at exhibition views of The House of Cyprus, a relatively small mansion packed with loud sculptures. It is an atmosphere made visceral by Jeffrey Deitch in an interview with Galleries Magazine in 1990: “One Saturday, shortly after the opening of ‘Cultural Geometry,’ Dakis and I were walking around SoHo. Suddenly, we found a kind of convergence of ideas in the work of artists like the Neo Geos – a new way of dealing with nature in our consumer culture. In an hour and a half we had acquired pieces by Meg Webster, Bill Stone, and Martin Kippenberger.”

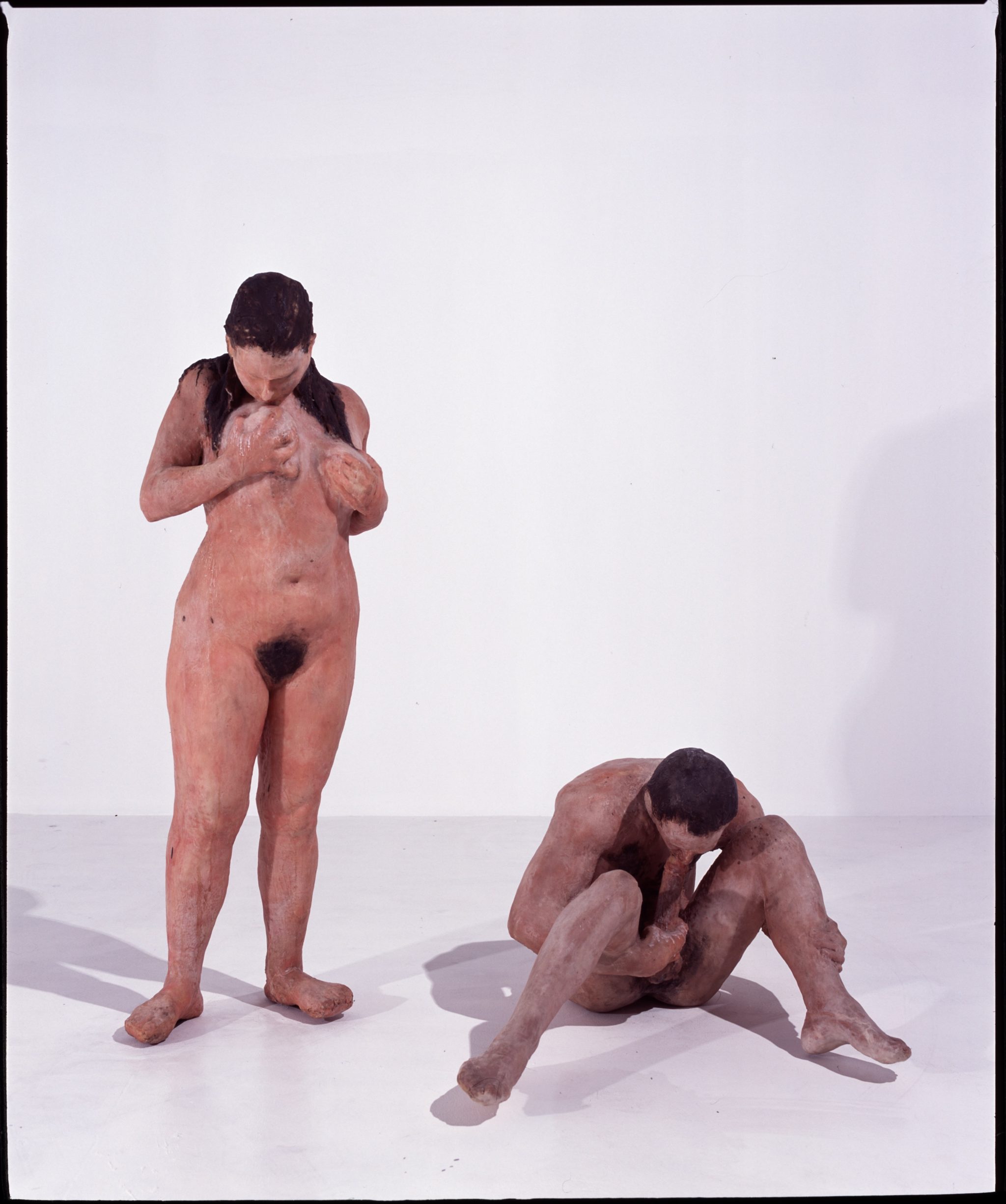

Curated by Deitch, 1996’s “Everything That’s Interesting is New” – which featured over 100 artists and 200 artworks – was a show that brought the scale of DESTE’s exhibitions to a completely different amplitude. In one perfect exhibition view, a vast white factory filled with artworks (including an Andy Warhol Brillo Box) is shot through the glass of Koons’s Equilibrium Tank, with its haunted basketball floating in the foreground. But the largest and most recent of Koons’s works – a sculpture entitled Moon that had been in construction for two years – did not make it into the exhibition. As Joannou describes in a text recalling the exhibition, he had to arrange for one level of New York’s George Washington Bridge to be closed in order to get Moon to the airport and en route to the exhibition in Athens. After a jumbo jet made a pit-stop in Greece to drop off the piece, Koons inspected the work and told Joannou that it was not in the right condition to be exhibited. The sculpture was then destroyed, and Kiki Smith’s Bowed Woman was installed in its place.

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, Manhole, 2001

The cars arrived at the hotel at 8pm and transported us from our lodgings at Dakis Joannou’s New Hotel in Central Athens to his private home in a suburb called Nea Ionia. The area, including the home we were visiting, had a distinct 1980s white-stucco texture, somewhat of a global calling card for affluent neighborhoods in warm climates – from Naples to Palm Beach to Montevideo. Joannou himself greeted us at the door, wearing a dark suit and an inviting smile, somewhat of a signature look. I noticed he was wearing a large, silver belt buckle. He immediately ushered us into a private gallery to the left and downstairs from the entrance. The group of us proceed to ooo and aaa our way through a narrow salon filled with possessed, anthropomorphic sculptures by Andra Ursuta. The room then opened up onto a larger gallery where caterers awaited us with glasses of sparkling white wine. I later heard from one of the collector’s favorite artists that the marble floor of this second room was discovered by Joannou himself while skin-diving off of his yacht. It was then ceremoniously pulled out of the ocean, much like Elizabeth Peyton and Matthew Barney’s sculpture at the first DESTE Slaughterhouse exhibition in Hydra.

Up another flight of stairs and through a narrow corridor, we were led to a cocktail hour in the living room, where all the visitors quietly dispersed to oggle their surroundings. The room had a density of objects that felt more human than the white cube below our feet. Here, the colorful evidence of a life entangled with art overflowed in a melange of clashing patterns. Fashion photographs, sculptures, and 1960s Italian furniture mixed freely with family snapshots, including a giant portrait of Joannou’s daughter taken by Juergen Teller. Near a leopard-printed “Safari Couch” by Archizoom, I gazed at a bowl of shelled and peeled pistachios. Somehow this sight, more than any of the others, truly gripped me with the fact that I was in the home of a contemporary Medici. I heard a rumor that Duchamp’s Fountain was somewhere on the premises, but it felt impolite to ask. On the other side of the house, a set of Helmut Newton and Robert Mapplethorpe prints presided over Joannou’s empty home gym with their hard beach-bods. It reminded me of a hypothesis a former professor once had about the all-female selection of portraits in Henry Clay Frick’s study. She told me that the Gilded Age collector “liked to have women watching him while he worked.”

Dinner was served in the central courtyard of the home. It was September and the weather was a breezy shade below body temperature. The occasion was the incipient announcement of the DESTE Prize, a biennial award given to a young Greek artist. The prize was to be bestowed by the foundation the next day, but on the eve of the ceremony, Joannou wanted to break bread with the six finalists as well as the jury members, which included visiting museum directors Max Hollein of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Bernard Blistène of the Centre Pompidou. The collector himself was to be one of the jurors, and when we spoke to each other at dinner, he seemed thrilled about the idea of spending the next day locked in a room talking about art. During our first conversation, Joannou and I discussed Paul Chan’s Hippias Minor, which I had just visited on Hydra. We spoke about a chat he had during the opening – an early summer bacchanal, attended by his entire network – with three of his artists who had been moving away from creating objects and towards publishing digitally and in print. Half in jest, Joannou poked at the existential threat this posed to someone whose life is wrapped up in objects. What things are we going to put in the museum of this decade? It could be empty. Yet, for Joannou as with all people, things seem to be surrogates for something else.

You spend a lot of time with the artists you collect. Do you ever give them input on what direction they should take with their work?

DAKIS JOANNOU: No, I just talk and go wherever the conversation leads us. There’s no agenda or program.

They’re all friends of yours.

Exactly. I’ve been friends with Jeff for 33 years now. It’s a very interesting relationship. Maurizio, I’ve known for 15 years. We’re very close. We talk about a thousand things. Relationships are key to me. In a way, the collection is a byproduct of these relationships.

Tell me about how your relationship with Dakis developed.

JEFF KOONS: After he acquired the Equilibrium Tank, Dakis made contact and invited me to Greece. As an artist, I had never really befriended a collector. I was a bohemian artist, and it seemed like artists should stay a little distant from collectors, as far as friendship was concerned. Anyway, I went to Greece and met Dakis and Lietta and I was completely disarmed. And to this day, I really base many aspects of my own life on how Dakis and Lietta live their lives. Their priorities are that people and friends are above everything. It’s really about being interwoven in your community. And so immediately when I went to Greece, we went out on one of Dakis’s boats, and all of his friends would come and tie up their boats and spend their afternoon eating and talking. It was really about the joy of the company of people. And, to this day, I realize that’s what Dakis really loves about the art world. He’s curious about the objects and images that are created through art, but really it’s the interaction of people and potential that everybody has and the richness of the interaction of ideas and a dialogue.

When did you feel you stopped being a “bohemian artist”? Or do you still feel that way?

I don’t have physical needs, because I was brought up to have a sense of self-reliance. I enjoy art for the pleasure, or its intellectual stimulation and physical stimulation. I enjoy life that way. So, if I’m walking down the street and I see shorts in a store, I’ll look but I’m not really a buyer. I always feel like what I have now is nice enough. So I’m really not involved in consumerism on that level. I’m involved in a dialogue of desire – and the interior life of the exterior world. But I’m not really one that needs possessions. But I do enjoy collecting great art!

Dakis’s world is completely saturated with objects. As a friend of his, how would you describe his relationship to these objects? Is it intellectual? Is it libidinal?

MAURIZIO CATTELAN: Most importantly, collecting needs to avoid the didactic, to avoid strategy. And Dakis manages in this. I wouldn’t define it as intellectual, or libidinal. It’s about an unreasonable love for art. I could not say I agree with him though: While Dakis loves to be surrounded by memories, I love to forget the past as soon as possible. But, you know, opposites do attract!

On paper, this idea that Joannou’s massive collection of blue-chip artwork is a “collection of friendships” seems like a vacant nicety. But sitting at a table in Joannou’s courtyard, the feeling was more than palpable. Despite the blanketly good things I had heard from acquaintances of Joannou, I travelled to Greece expecting to meet a Hellenic hybrid of Stefan Simchowitz and Dominique Strauss-Kahn. I was therefore surprised to find myself completely at home and comfortably reclining into a wine buzz at Sunday dinner with Joannou, his wife Lietta, his daughter, and his DESTE Foundation “family.” The artists sitting at the table were likely sinking into a similar feeling. What initially felt like a stiff encounter between artists and curator-jurors had almost completely thawed into a Mediterranean revery within hours. It made sense why Joannou had immediately invited a young and “bohemian” Jeff Koons to this world, to a place

that was ancient and yet completely and utterly his. But what looks like a “group of friends” up close, appears as a “cabal” from far away. And while I was taken by the generosity that Joannou extended to me and everyone around him, the experience was also an affirmation of the widespread suspicion that the world is still run by closed-door groups of white men. Social reality was the fly in this soup – the wedge that divided a man who deeply loved art from the people camping outside of ATMs just kilometers away.

I first heard the name Dakis Joannou in 2010, in an academic cloister in Uptown Manhattan, where a group of critics who were instrumental in codifying the latter half of 20th Century art-making – in this case by spiking it with French theory as opposed to cash – were outraged about an exhibition at the New Museum. The show was called “Skin Fruit” and it was inspired by mutated visions of the body posited by artists such as Cindy Sherman, Charles Ray, Robert Gober, and others. It was curated by Jeff Koons and composed of works from Joannou’s DESTE Foundation, who was also a trustee of the museum. This alignment of interests inspired a wave of critical backlash towards the show, one that art historian Alexander Alberro was able to encapsulate for me succinctly.

How would you characterize the response to the New Museum’s “Skin Fruit” exhibition?

ALEXANDER ALBERRO: That the collection of a trustee of The New Museum was being featured in that very same museum seemed to be an evident conflict of interest. What was more troubling, however, and what many found scary about this particular incident, was that the trustee of the museum and the artist-curator involved didn’t even feel the need to cover up the conflict of interest. Rather, they went public with it as if it were business as usual.

What were your thoughts on the show itself?

ALBERRO: The show only featured work by blue-chip artists, and not particularly important pieces by these artists. I found it quite boring. Someone seems to have given the collector an A-list of artists, and it looks like he went straight down that list and bought at least one of each. Yet, the important thing about the show, and what made it the first of its kind, was that those involved were so blatant in flaunting what they obviously deemed to be the no-longer-relevant detachment between museum trustees and the exhibitions featured by the museum.

If a constellation of power such as the one behind “Skin Fruit” had been assembled in finance, it would have been classified under the crime of “insider trading.” But – for better or for worse – the boundaries of the art world are much more soft and pliant than those of the stock market. On its face, contemporary art has come to represent the inclusive attitudes of modernity, but the forces at play behind it continue to be dictated by medieval clusters of personalities. Museums depend on the generosity of collectors to fill their galleries and their coffers, and while this is normally done in the name of charity, it seems optimistic that these interests – whether they be tax-related, speculative, or simply a matter of prestige – would remain quarantined from public institutions.This is a reality that potentially puts “un-marketable” artwork in crisis. But Joannou’s violation with regard to “Skin Fruit” seemed to be less about what he did than how he did it – as though the Cypriot had driven his Jeff Koons yacht straight from Corfu and collided it into The Statue of Liberty, as though he smashed through the walls of the institution from the outside to take a naughty peek, as in Maurizio Cattelan’s famous sculptural self-portrait. In fact, it was the baldness with which Joannou did something that collectors and museums had already been doing for years that brought to the fore a very necessary conversation that none of the parties involved ever wanted to have. Years later, the collector remains unapologetic.

I first heard about your collection at Columbia University, when your “Skin Fruit” exhibition was happening.

DAKIS JOANNOU: Ah, this big scandal!

It became this example of collusion between museums and collectors.

Joannou: It’s totally pathetic. First of all, the museum asked Jeff to curate the show. And Koons chose me. He accepted and chose the pieces. It was his show. I had nothing to do with the selection of the pieces in the show. There were some great works and some less great works. The installation was incredible, but nobody really looked at the work. Instead of really looking at the show and discussing this period represented in my collection, they immediately jumped on the fact that I was on the board of trustees.

Do you think it’s a problem for artists who don’t make collectible work – that museums and collections have become so close to each other?

But that case doesn’t happen every day. Of course, if a museum only were to show collections, then it’s not doing its job. Now they don’t dare do it any more. How much extra value are you going to add to Jeff’s tank because it was shown at The New Museum? Or Mark Bradford? People know who he is. He has his market. Just because I put a Mark Bradford in a museum, doesn’t mean it’s going to change the market of Mark Bradford. It’s nonsense. I completely ignored this. I didn’t want to deal with these issues at all.

In Joannou’s view, the very fact that the DESTE Foundation is not a public institution is what gives it strength – an outlook that bypasses the question of what private wealth owes the public. In Athens, museums seem less conflicted about the prospect of displaying his collection. During my visit, I went to DESTE’s Ametria exhibition at the Benaki Museum, a gargantuan and maze-like display filled with a mix of historical artifacts and contemporary works by artists such as Urs Fischer and Terence Koh. With its black walls, unlabeled artworks, and phantasmagorical lighting, the exhibition felt like it was designed to support an almost sexual engagement with the way things look, no matter what they are or where they come from. It was an experience so unilaterally frivolous that it seemed unlikely to have ever come from the mind of a market speculator or a public institution. After dinner at Joannou’s house, a painter whom he collects described an evening when the industrialist called him from his bathtub at 11pm, to tell the painter about a book that reminded him of his work. During a conversation, Joannou told me that he feels proud when artists from Greece and abroad tell him that they were exposed to transformative ideas by things they saw at one of DESTE’s exhibitions, yet he maintains that any social good brought about by the activity of DESTE is simply “collateral.” Joannou’s contri-bution to the contemporary art scene of Greece is enormous and undeniable, but exactly what this public benefit is collateral of is something that remains a mystery.

Kiki Smith, MOTHER / CHILD, 1993

In The System of Objects (1968), Jean Baudrillard argues that possessions are as necessary to the psyche as dreams. Certain objects help us as instruments for living, but others (the objects we possess just to possess) are ways of anchoring ourselves in the perpetual flow of time. These objects are the things that we use to pour our lives into something inanimate – into something that allows us to watch ourselves as viewers from outside. As consumers, our facewash-toner-lotion combo is designed to reveal as much about us as the bathroom mirror under which they lie. Time has shown that fracturing the psyche into a constellation of objects – making a collection – is a good way to become immortal. It’s more detailed than a statue, more able to tell a full story. But the process itself, as it transpires, is one of continually experiencing the boundaries of life-death.

During the making of the DESTE exhibition “System of Objects,” (2013) curator Andreas Angelidakis recalls a moment of meticulous object-love, in which Joannou stopped a slideshow to correct a small mistake in the dimensions of a painting he bought more than 15 years prior. In the exhibition, Angelidakis and co-curator Maria Cristina Didero placed a baroque statue of a baby Christ in front of a Francis Picabia painting from 1942. The statue watches the painting, and the painting watches it. Here we a see a collection that has grown into a self-sustaining world, with its own actors and agents. It is a relationship between objects that reminds us what the word “fetish” originally meant – such as in Voodoo, or in the way Karl Marx describes commodities living independently of humans in a market. It is the magic of an object that is given life by desire, or rather an object taught to desire by the humans who desire it. As Baudrillard writes: “We cannot live in absolute singularity, in the irreversibility signalled by the moment of birth, and it is precisely this irreversible movement from birth towards death that objects help us to cope with.” Reading these words, I imagine Joannou floating on the Aegean Sea in the lacquered womb of his yacht, furnished by the spilt contents of his mind, surrounded by the friendly monsters of his own collection. I imagine him being born again, smiling.

In Germano Clemant’s introduction to your DESTE retrospective book, he speaks about how collage is this basic and fundamental gesture of the avant-garde – and how the word comes from the French coller, “to glue.” As a collector, do you feel like your ambition is to glue things together?

DAKIS JOANNOU: You’re right! Even that’s a collage!

But what makes your collection more than a group of objects?

I think I make connections that a curator would not make. For me, there’s something else that ties things together. The same psyche.

Tell me more.

I’ve been trying to explain this. I read an interesting definition of “Hellenism” by a writer. Greece was never a geographical entity until 150 years ago. It was a spirit, or an idea. Greeks were from Sicily, from Georgia, Northern Turkey, Cyprus, Libya. Various parts of Greece were not even joined together. But what connected all these areas was the psyche. And these were different cultures and populations, but they all shared a spirit. I’m still trying to find an explanation of the phenomenon of the collection. It grew naturally without me realizing it, but at a certain point – when I realized how distinct works are and how they weren’t formally fitting together – I tried to find the common thread. What Jeff often says is that it’s the viewer who really energizes the work. One puts in it as much as one takes out. In that sense, I think it’s important to have this relationship with works. You become part of them, and they become part of you.