RICH THINGS: How Tourism, Sneakers, and Museums Make the Economy of Enrichment

|Victoria Camblin

The term “late capitalism” has been around for decades, but today it shows up everywhere, prowling political and cultural journalism, equivocal and suspect. It is a “catch-all phrase for the indignities and absurdities of our contemporary economy,” as The Atlantic put it last year, one that suggests we live in the overdue twilight of the modern West: “late capitalism” contains the prophecy of its own end.

Understandably, nobody knows when it will be over or what (if anything) comes next. Yet we’re equally in the dark about the nature and mechanisms of this volatile period of consumption and valuation, in which Supreme sweatshirts sell on Grailed for 1,400 dollars a pop and industrial fixer-uppers occupy the most inaccessible regions of the real estate market. Enter sociologists Luc Boltanski and Arnaud Esquerre, whose recent book Enrichment: A Critique of Commodities (Enrichissement: Une critique de la marchandise, Gallimard, 2017) describes the advent of a capitalism based on tourism, luxury, cultural heritage, and the arts – an unaccounted for “economy of enrichment,” the articulation of which has the capacity to reveal the character of our contemporary reality, and perhaps provide the tools to change its course.

Objects, not fortunes, are at the heart of this new economy, in which growth is contingent on how we assign value to things, and amassing them is central to the acquisition and expansion of wealth. Agents of the enrichment economy are neither financiers nor industrialists – the movers behind traditional descriptions of capitalism – but creatives, travelers, and culture makers who, in circulating contemporary art, luxury fashion, high design, and international real estate, participate in capitalist enterprises they might have remained blind to, until now.

Among the paradigms of consumption described in Enrichment – which include a “standard form,” an “asset form,” and a “trend form” – the neglected “collection form” is the most powerful, capable of endowing an old, useless, or mundane object with new and incredible value, by virtue of its ability to tell a story of worth, tradition, or immortality.

The story of the current economy is narrated in the refrain of Charles Baudelaire’s “Invitation to the Voyage,” which famously calls for “Luxe, calme et volupté” – roughly, “luxury, peace, and pleasure.” These are riches that, according to Boltanski, economists want us to have: a material environment that is sumptuous but stable, secure, and unperturbed by external disruptions such as financial crisis, war, or ecological disaster. When we met at Paris’ School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences, Enrichment’s co-authors offered no predictions as to how the enrichment economy might weather such crises – or what the idealisms of this new framework may have to do with that spectral “end” of capital as we know it.

As long as the luxury matrix stays comfortable, the perfumer and the performance artist, the creative director and the CFO can comingle and cross-pollinate without undermining the creation of value and puncturing the bubble. The economy of enrichment will invite these individuals to voyage, to deterritorialize digitally, across disciplines, and geographically as they drop pins in new ateliers, airports, and DJ booths, hitting Milan for the Salone and Mallorca for Memorial Day, London for Frieze and Paris for fashion week. Amid the cultural splendor of the city of light, rich in art, fashion, and tradition (and tourists), Boltanski and Esquerre were convincing: change is inevitable, stability is illusory, and whichever one you crave – revolution or volupté – a revealing look at the would be invisible forces at play is essential, and urgent.

Was it while traveling that you began to notice the economic patterns you describe in Enrichment?

LUC BOLTANKSI: It was primarily from traveling in Paris!

ARNAUD ESQUERRE: The movement of what we call the enrichment economy is particularly strong here, and that’s why we chose France, and Paris in particular, as the focus for our reasoning. There is an ensemble of activities that includes tourism, luxury industries, and cultural heritage concentrated here in Paris. And this concentration has only accelerated since the 1980s – the number of investments in luxury commodities are increasing, and luxury goods conglomerates such as LVMH, or Kering with François-Henri Pinault, are creating foundations. Luxury real estate has grown so much in Paris that we are now seeing the same consequences as in Barcelona or Venice, where the increase in the price of real estate connected to tourism has moved local families out of the city. Cultural activity and cultural heritage are tied to this narrative. It will seem anecdotal, but, for example, the Carters’ music video shot in the Louvre recently is absolutely characteristic of the story of the enrichment economy, in terms of the development of an idea of cultural heritage, and of tourism. In France, there were almost 90 million tourists in 2017.

France remains the most popular tourist destination in the world, I believe.

LB: And initially, sociology wasn’t interested in tourism, especially in France. There was some interest in exotic tourism, in order to critique it as colonialist – but without realizing that we are in fact the “natives” of global tourism! Now it’s a theme that is beginning to become important, especially since numbers have come out indicating that tourism is responsible for 8 percent of global warming. That’s what connects our work in Paris to riots in Barcelona against Airbnb, for example, protesting displacement. You know, the industrial revolution is something that in the beginning touched only a few counties in England, but that then expanded and changed life on the entire planet. And just as the critics of the industrial revolution – including Marx – were lucky to have lived in England, we’ve been told we are lucky to live in Paris to work on the enrichment economy!

Was there a particular catalyst within this French context that made you think, “We’ve got to write this book, immediately”?

AE: What we were seeing around us was something very different from traditional descriptions of capitalism, which either turn toward financial markets or, on the political left, toward labor. Each of us had a different entry point: Luc was very interested in the question of collecting and the function of the collection; I was studying a region in the South of France that was striking because it had undergone a complete transformation economically, reorienting itself toward tourism and cultural heritage, and marketing traditional artisanal production that didn’t even exist before the 1980s. So, departing from a fairly simple amazement at these phenomena, we asked ourselves, “How can we describe all this?” We began leafing through things like the Air France in-flight magazine with a kind of distance, to understand why what we were seeing there had come to be accepted as self-evident when it didn’t even exist 30 years ago.

LC: It seemed to us that over the course of the last three to four decades, in certain countries and locales – in what we call “basins of enrichment” – a great change occurred, but was essentially lived, without being theorized. It was lived without being named by sociologists or economists, and by the same token, it wasn’t seen by people invested in politics – neither government officials nor political theorists. Our impression was that there was a delay in the way in which we were talking about society – that the judgment that could have given us a description was running late. On both the left and the right, the big idea with French politicians is that we have to reindustrialize France and reconstitute a working class that has undone itself. With a somewhat curious twist from the left, for whom the factory – which was considered as what it was, a place of oppression, when I was 20 years old – has now taken on a nostalgic, idealist character. Our position was realist. What is the mode of production of wealth in France today?

So this new form of capitalism was invisible to the Vuitton consumer and the tourist who leaves their Airbnb and visits the Louis Vuitton Foundation – but also neglected by those who might theorize these behaviors and institutions?

LB: The very well-intentioned discipline of sociology has historically been mostly interested in the poor. There is a school of sociology that needs victims – with human faces – to give itself a purpose. There were more general discourses, largely poorly founded, on the effects of financial markets, the birth of neoliberalism, and so on. But where does the money from finance go? What do finance people do with the money that they make in financial markets? There is practically no information about this. We have a little bit of literature in sociology about the wealthy, but it’s a literature that gives a spicy description that is a bit “lives of the stars,” describing all the awful things rich people do, like bathing in champagne. Of course that’s a crowd-pleaser, because you have a victim on one side and then monsters on the other. In Enrichment, we show the new forms of exploitation. We just don’t have a massive staging of victimhood. We wanted to move the problem away from people and toward the question of wealth itself. That’s why we came back toward things.

AE: Art and culture are at the heart of this type of economy. The conception we all have of the work of art is that it exists outside of the capitalist economy – it has to be the expression of an intention of the artist, it has to be incomparable. We still see capitalism as the great threat to art and culture – specifically, industrial capitalism, which uniformizes production by fabricating a large number of models based on a single prototype. The received idea, which starts with the Frankfurt School but is still widespread, is that capitalism will homogenize the work of art in the same way, and so there is an attempt to divorce it from that. Also central to the enrichment economy is the figure of the tourist, who is opposed to that of the traveler: the traveler is disinterested, oriented toward art and culture, and tourists are oriented toward capitalism, spending and bringing in money wherever they go. The fact that we maintain these distinctions is why we are late in the understanding of this type of economy. So what we did was to regroup these types of activities to show their connections – which was difficult to do because we don’t have global statistical frameworks that allow us to measure anything. So people often reproach us, saying –

“Give me the data!”

LB: One of the reasons these phenomena are poorly synthesized is that economists and statisticians continue to use categories that don’t function well anymore. When you take a poor agricultural region that had been quasi-deserted in the 1970s, and that in the 1990s became a region where something relatively opulent was happening, you have fallout that attracts things like antique shops or, as someone I once encountered called himself, “heirloom tree dealers” – antiquarians of trees! These things are symbolic of massive changes in social structure, but they are very difficult to identify in any official documentation.

AE: We have enough data to show that tourism is high, that luxury industries are booming – but we are missing the data sets because our system wasn’t constructed to measure these phenomena. Another thing that’s important from our theoretical point of view is that capitalism, in the world at large and within the economy of enrichment, requires difference. Which means that profit, in fact, comes from difference – a relationship that people in fashion have understood very well, evidently, but which is used in the arts as well, even if people don’t care to admit it. In order to be profitable, capitalism needs a constant creation of new differences, and what collectors are looking for is the latest difference. Hence the significance of the collection – because a collection is above all a collection of difference.

“In order to be profitable, capitalism needs a constant creation of new differences, and what collectors are looking for is the latest difference.”

You mention that an outmoded exceptionalism in the arts has contributed to a delay or a handicap in our ability to perceive the development of the enrichment economy. To go further, there is also an expectation of artists to lead the criticism of these economic forces. So it would seem that what is holding us back is a hypocrisy too: the arts embrace their critical reputation yet fail to acknowledge their major role in the late capitalist economy, as producers of luxury goods, and of wealth.

AE: We think of a masterpiece in the Louvre as not having a price, but of course that’s an illusion – every artwork in a museum has a price: its present day insurance value. When the Louvre museum was created, the works were indexed and a price was put on each one, assigned with the help of Parisian dealers. One of the points we emphasize in Enrichment is that contemporary artists are part of this economy, despite this tendency we have to present them as external. Look at Kassel – Documenta presents itself as somewhere artists are able to express critiques of society or capitalism, but the works of art exhibited there are sold and collected afterwards, and thus participate in this type of economy.

LB: There’s something we see poorly because it is taken for granted, because it is so widespread, which is the degree to which sociological thinking and economics have centered themselves around the industrial economy, as though it was the extent of the world. It was as far back as the 1930s that art was really conceived as being the locus of exteriority – the “outside” in contrast to industry. Because it’s irrational, incalculable. And this applies to luxury too: Georges Bataille, for example, considers luxury goods as a way of criticizing industrial society – because luxury has to do with the decay of materials, with an apparently irrational expenditure. What we are trying to show is that the current vision is partial and dated, and that we can now have the development of a capitalist society in which entrepreneurs are seeking profit, but that is no longer centered around the question of industrial production. The basic rules of the economy of goods and objects are changing.

How?

LB: One of the first remarks that came to us after making this work was that when you have an industrial object, it is self-evident that its price is necessarily going to go down with time. I’ve talked to designers about this – why is it that when you are shopping for a refrigerator, they’re all white? If you have a scratch on this white surface, it loses 50 percent of its value. It still works just as well, and if this scratch is such a big deal, why do we make them like that in the first place, since it will mean that the scratch will be visible? It’s bizarre, right? Well, it’s because this immaculate whiteness is the sign that it is completely new, right out of the factory, and that no one has ever touched it. The question of touch is very important in all of these problems. As the fridge gets progressively touched, it will lose its value. But in interesting ourselves in collecting, and in luxury objects to the extent that they are intended to be collected, we find ourselves in front of another phenomenon we have no real numbers for: the objects that increase in price progressively, as time passes. I have never read an economist who takes account of these types of processes.

AE: Why does the price of collected objects increase? Sure, you can make collections with objects that have very low prices, but what is interesting is that objects with very elevated prices are collected precisely because that’s a way of stocking wealth. So how do you store wealth? One thing we see very clearly in contemporary art is that, in the countries we call “emerging,” or, in any case, where there have been very significant phenomena of enrichment, with big fortunes appearing, the price of their artists increased at the same time. The price of Chinese contemporary art augmented considerably in connection to the emergence of wealth in China.

Personally, I can’t read Enrichment without thinking of its American applications, particularly in former industrial centers.

AE: In France and in Italy, it’s particularly developed with respect to the size of the country, but sometimes it can touch only one city or one neighborhood. When we presented this work in New York, the remarks we got were, “Oh, what you’re saying is very old Europe. Here in New York, the city of finance, we don’t have that.” Then you look at the High Line, and you see an industrial heritage that has been presented in the exact terms of the enrichment economy: you have luxury boutiques, you have the biggest art galleries in the world – and it all corresponds exactly to the type of transformation we’re describing. So the idea can be completely transposed to other types of places. But you need a cultural heritage to exploit, a narrative that can’t take place just anywhere. The tourist moves around in response to the image, to the story of the place that they are going to go to, and with respect to what is highlighted of its cultural heritage.

“There has to be a brand name, there have to be associations, there have to be other t-shirts that pre-exist it. It can’t be just a t-shirt.”

Let’s talk about this notion of the “story” – a term that is very important in your book, and a word that is used a lot presently in marketing. Start-ups, for example, are always talking about “storytelling,” creating and distributing an origination narrative about how and why they came to be – a story of purpose that boosts the relevance and significance of a product or a brand. Can you speak a bit to how you came to this term, this analysis?

LB: One of the elements that caused us to emphasize the idea of the story, especially in the context of collections, is the question of the fake. Take two identical drawings that are both attributed to a major artist, but one is real and worth 100,000 dollars, and one is fake and worth nothing at all. Or take General de Gaulle’s leather jacket, which is exhibited at the military museum. It’s a 1940s leather jacket, just like the ones you find in the flea markets. What makes the difference between the real drawing and the fake drawing, and between the leather worn by de Gaulle and the one at the flea market? In both cases, the object has touched, has been in physical contact with, a particular person. To really receive these small differences, which will create colossal differences in price, you need that story, because they’re not visualized in the object itself. An industrial object does not have a story.

These are all stories that have to do with the past. What about objects that promise you the future? Where the story says, “If you buy this, you will be a part of something that’s about to happen”?

LB: Within the enrichment economy, an object’s value is attached to the past. At the moment, I am shopping for a new telephone. There are series of specifications – the screen has a certain amount of pixels, the battery lasts a certain amount of time. I don’t know what half of it means, but there’s no need for a story because the object is guaranteed by the manufacturer, and I just need information on its functions. If it was to become a collectible iPhone, you would have to tell me that it’s the one with which Johnny Hallyday learned he had a mortal illness. In that case, you have a story that will give extraordinary value to this object because it reattaches it to the body – of Johnny Hallyday! He had it against his ear when they told him he was going to die.

AE: You are right with respect to the future when it comes to contemporary art. Why is art that has just appeared already part of the enrichment economy? Effectively, you have to envisage a future in which the work of art will be inscribed as a part of history.

LB: Something eternal.

Are we in crisis in terms of our relationship with objects?

AE: People’s attention has been brought to a world where everything is digitized, everything is computerized, whereas there have never before been so many objects around us – and our modes of commercializing them are evolving a great deal. Let’s think about those things, their circulation, their purchase, their sale. The Internet has created a non-stop consumption, so there’s that, but it also really modified our relationship to price. All of a sudden, there are a bunch of different prices for the same thing – which is something the industrial economy really tried to eradicate.

That’s something we sought to describe: why does the value we attribute to objects vary so enormously?

We know the volatility of prices in the art industry is extremely dramatic; one auction result can change an entire collection’s value. What about how we assign value in the luxury goods industries, where products that are materially very similar can vary tremendously in price? Would you say the luxury industry is more transparent than the art world in terms of its relationship to capital and prices – and perhaps less burdened by the expectation to execute a critique?

AE: Well, one of the principles of the luxury industry is the power to increase profit by making something collectible. Engaging artists is one way to do that. That’s why you have collaborations with very famous artists who will be used, who will be invited to make objects that are at once luxury goods and collectible objects. It’s true that you don’t have the same critical aspect in luxury industries as you do in the arts. Although one of the issues there is our habit of presenting not only artistic or creative directors of fashion houses, for example, as artists themselves, but also of presenting founders or namesakes in that way. Luc and I were at an exhibition about Louis Vuitton, and Vuitton, who in the beginning was a maker of suitcases, today is presented as an artist, his life retold as that of a créateur. A critical narrative emerges when you have a créateur who has developed his brand, which is then acquired by a conglomerate, and the name is preserved by the company that purchased it even after the original designer is eliminated. Suddenly, the designer looks like an artist who has been dispossessed. It’s the moment at which it is revealed that there is a purely financial logic to the industry and to the label: when the person who was at the center of the brand finds themselves suddenly on the outside.

LB: Of course, if you buy something expensive, a luxury object, it’s not because you’re trying to criticize it! I suppose you could criticize the price, but within the active form of consumption, the more the price is elevated, the more the object is interesting. You can imagine that its price will continue to rise: just like any active good, if a Jeff Koons is very expensive but its value is still going up, then you’re still getting it at a good price. It’s only a bad price if the value is going to plummet.

What do you make of the “streetwear” phenomenon? These are clothes made of cotton, and it’s very good quality cotton, but it’s still a sweatshirt for 1,400 dollars. It is expensive and a “trend,” but it is also collectable.

LB: Another internal critique is made by people in the luxury industry when they turn and look toward their own activities, and unveil that the luxury object is not produced artisanally in the countries that value them, such as France or Italy, but are in large part produced industrially in countries where salaries are low. That’s an appealing internal criticism. But what you are describing is what we call the “trend” object, which introduces that profitable difference we have spoken about. Trend-based consumption is unique in form because it’s circular. You have a créateur who makes a t-shirt that’s missing a sleeve. T-shirts have two sleeves, this one has one, and that’s the only difference it has. It’s going to be fabricated in limited quantities and it will be expensive. But because it’s only really a difference in style, other manufacturers are going to be able to reproduce that difference. They will do so very fast, and they are going to make a lot of them. The difference won’t be a difference anymore, so it will have to be hybridized with other elements – it will have to be given a rhinestone. The original fell out of style, and the créateur had to go out looking, and now the one sleeve has a diamond on it. That’s why designers spend so much time at flea markets! They know it’s circular, so they’re going to look at what is démodé, for elements that will recombine differently to relaunch the process.

AE: That’s the process of enrichment: you have a trend product, and its producer increases its price by making it collectible. For something to be collectible, you have to have an ensemble – of course, it’s possible to have a collection of t-shirts, but to be able to sell a t-shirt for a very elevated price right from the beginning, you have to have a whole bunch of devices in place: there has to be a brand name, there have to be associations, there have to be other t-shirts that pre-exist it. It can’t be just a t-shirt.

It’s the story.

AE: It’s the story.

Is the value of an object of enrichment then simply a question of auteurship? Those authors being artists and créateurs, or maybe a clothing company, a private foundation, a culture ministry –

LB: I put out a book in the early 1980s on what we call cadres in France.

“Suits,” in English. Business executives.

LB: It’s a postwar model of social ascension, of “lifestyle,” and so on. We think that today the model of the créateur has in large measure replaced the model of the cadre. Look at Le Monde’s magazine supplement, for example, and you will see pastry chefs like Pierre Hermé presenting themselves as artists. And of course, more and more people consider themselves as curators too, and the presentations as their oeuvre.

In the book, you mention curators as part of a set of people who traditionally assign value to objects from an objective standpoint. But it’s not always transparent what the relationship is between the value of the object and the personal interest or investment of the person evaluating it. In English, we call this a “conflict of interest,” which seems impossible to measure or determine within the present day labor model.

AE: You have to maintain a position of exteriority for the valuation of objects, otherwise there is effectively a suspicion of personal interest. The problem there is that very often the people who are writing about art or objects and presenting them – it’s what we all do, really – are not the people who benefit from their appraisal. Not directly, anyway. But in reality, things are a bit more complex, which we see when major luxury conglomerates, who are big collectors and maybe have big art foundations, call on curators to organize exhibitions of artists that they themselves collect. Everything is bound up together, and this has implications for the repartition of profit. Conflict is hard to avoid because it is not thought about – because people continue to think that they are still on the outside of capitalism. Yet there is a very strong inequality, a part of the population that is precarious and exploited, because the enrichment economy corresponds to a labor model based on “passion.” With the passion model, there is no difference between what is work and what is not work. In creative fields, you have people who work all the time, in a certain sense – I imagine you know this problem! – and then you have people who are excluded from that simply because they are excluded from the story, from a narrative that exploits and highlights a relationship to the past.

LB: In fact, this is a condition of the functioning of an enrichment economy, and another possible reason for its delayed theoretization: the fact of being unknown. We have to ask ourselves in a more systematic way, “How would the economy of enrichment function if it was explicitly recognized by official institutions, by economists, by statisticians?” Certainly it would change deeply, in its allure. I must say we would have a dystopia of a world in which the enrichment economy is absolutely recognized as such, and as a source of wealth. This is quite different from what we know today.

There’s also this haunting presence when we talk about the dissolution of the industrial labor model from the position of Europe or the global West, because factories and workers didn’t disappear from the Earth, they’re just in other countries. It’s an overseas oubliette.

LB: Clearly. Just as we’ve never had this many industrial objects being made, they are being made in ever more dramatic conditions of production.

The types of objects and modes of consumption that you relate to the enrichment economy can fit into multiple forms of consumption – the standard utility-based form, the trend- and collection- based forms. So I wonder if what you are describing is not a new set of categories but in fact what we in Issue 34 of 032c called a “flattening,” a synthesis across forms of production and consumption. Are you under the impression that the borders between these distinctions are becoming flatter, more permeable?

LB: We don’t really make a forecast in the book. We wanted to leave that portion of the work to specialists, to economists and econometricians to respond to what the importance and future of the enrichment economy is. But what we think is that the enrichment economy is very fragile. First of all, it depends on rich people, so for it to develop, their wealth has to develop. And that wealth depends on other types of economies. The enrichment economy also depends on tourism. Baudelaire’s poem “Invitation to a Voyage” contains the famous line, “Luxe, calme et volupté.” What economists want above all is that luxe, calme, and volupté – they want a safe environment, with a lot of security. Things like terrorism are extremely vexing for an enrichment economy. We can also imagine a critique of tourism in which the tourist is at the center of both economic and ecological debate. That would be a real problem for the enrichment economy. So it looks more fragile than the old industrial economy, and maybe that will bring about crises of a new kind. We always talk about the crisis of 1929, then about 2008 – financial crises. But if we have a development of enrichment economies in highly developed countries, there would be an appearance of crises directly linked to that.

Journalists and culture critics have the peculiar role of porte-paroles within this economy – we’re the ones sharing and providing a platform for the stories that create wealth. What we say in 032c potentially leads to enrichment. Are we precipitating some kind of new crisis?

LB: It’s journals that propagate the stories, but it’s the academics and the art critics and the curators that create them.

But this notion of flattening has also led us to speak about “content” in new ways – publications aren’t really making a distinction anymore between what a curator says versus what an academic or journalist or even a company press release says. It’s all “content.” So we admit that, and we unveil the economy of enrichment, but then what can we do?

AE: There are two perspectives. One is that with an unveiling, the actors themselves can criticize or modify the way in which the enrichment economy functions. The other perspective, which Luc proposed, is the external perspective, anchored in reality – which is to say that if there are ever elements such as terrorism or ecological disaster, then that is the moment at which we challenge this type of economy, including those who participate in it.

LB: Normally, this should have led to a change with the artists. I’m not sure in what direction, because it’s true that the critical function of art is very difficult to absorb into a model like this.

AE: Unless it’s in a way that’s a bit hypocritical.

Credits

- Text: Victoria Camblin

Related Content

Exhibition and Empire: Decolonizing Museums Requires a New “Metabolic” Architecture, Says Curator CLÉMENTINE DELISS

The Real Thing: Exhibiting the Art of the Bootleg

It’s Been a While, Crocodile: Creative Director LOUISE TROTTER Gets to the Heart of LACOSTE

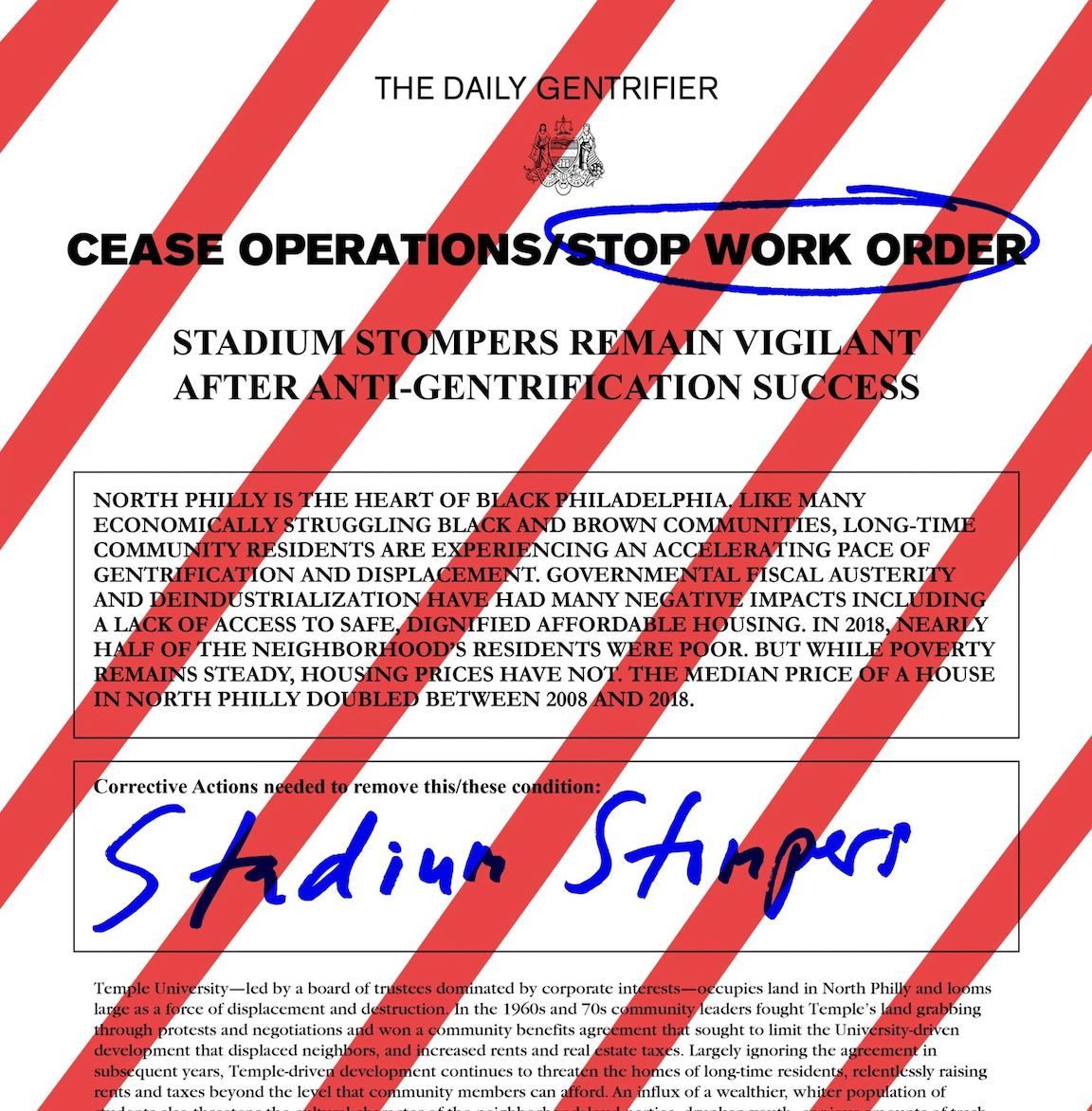

Not Too Twee: That is the answer. DUSHKO PETROVICH's “The Daily Gentrifier”