LOVE! INSTAGRAM! COMPASSION! Between an Ipanema bikini and an over-decorated cake, FRANCESCO VEZZOLI's Love Stories

|Victoria Camblin

FRANCESCO VEZZOLI describes his relationship with the Fondazione Prada as a “friendship,” and it goes back at least as far as Trilogia della Morte, a 2004 exhibition conceived for the Prada Group space at via Fogazzaro – before the unveiling of the foundation’s permanent and OMA-designed campus at Largo Isarco, its Osservatorio annex across town, its Venice outpost, or its activities in Shanghai. Commissioned for this early project was Comizi di non-amore, a work that plucks Pier Paolo Pasolini’s love and sex themed documentary Comizi di amore out of the world of Italian cinéma vérité and drops it into the context of early reality TV, which in the early 2000s was enjoying a first golden age as Survivor and Big Brother became massively popular, global network franchises.

One of the last cultural-phenomenal “things” to happen before Covid was the streaming reality TV show Love is Blind. Everyone I knew binge-watched it in semi-secret. Then, at dinner parties, someone would martyr themselves and bring it up so everyone else at the table could talk about it. Netflix reported at its Q1 meeting last month that the marriage-driven reality dating show had been watched by 30 million households across platforms, thanks in part to a reunion special released on YouTube on March 5. One or two weeks later, a bunch of lucky non-essential workers were sent home to self-isolate. If the single people among those workers were to continue to date, it would be in conditions reminiscent of the Love is Blind signature “pods”: they would be surrounded by pillows and blankets, drinking heavily and alone, their conversations mediated by the messy, tacky architecture of an imposed surveillance platform – on TV, a red velour cell bugged with mics and cameras; at home, a video conferencing app. While Love Is Blind participants were deprived of their phones and access to social media for the duration of their dating life in the pods – two weeks, roughly – as young professionals went into self-isolation, Instagram was deprived of its typical content. The platform could (maybe mercifully) no longer be used to broadcast travel and socializing, and became instead a Pinterest of nostalgia and chagrin, a mood board of home improvement projects and home-baked goods, punctuated by tone-deaf vacation memories and memes about confinement, deprivation, horniness.

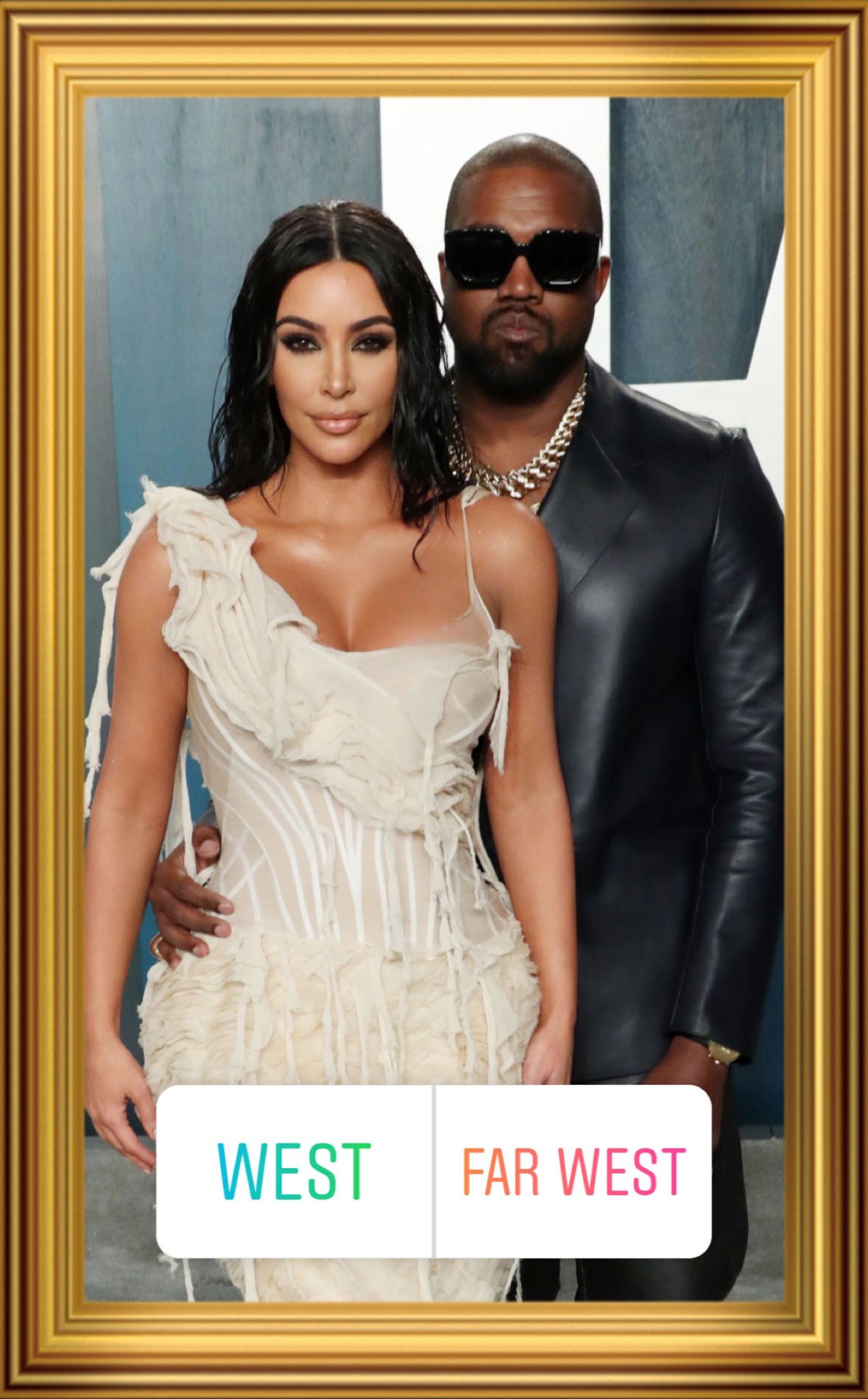

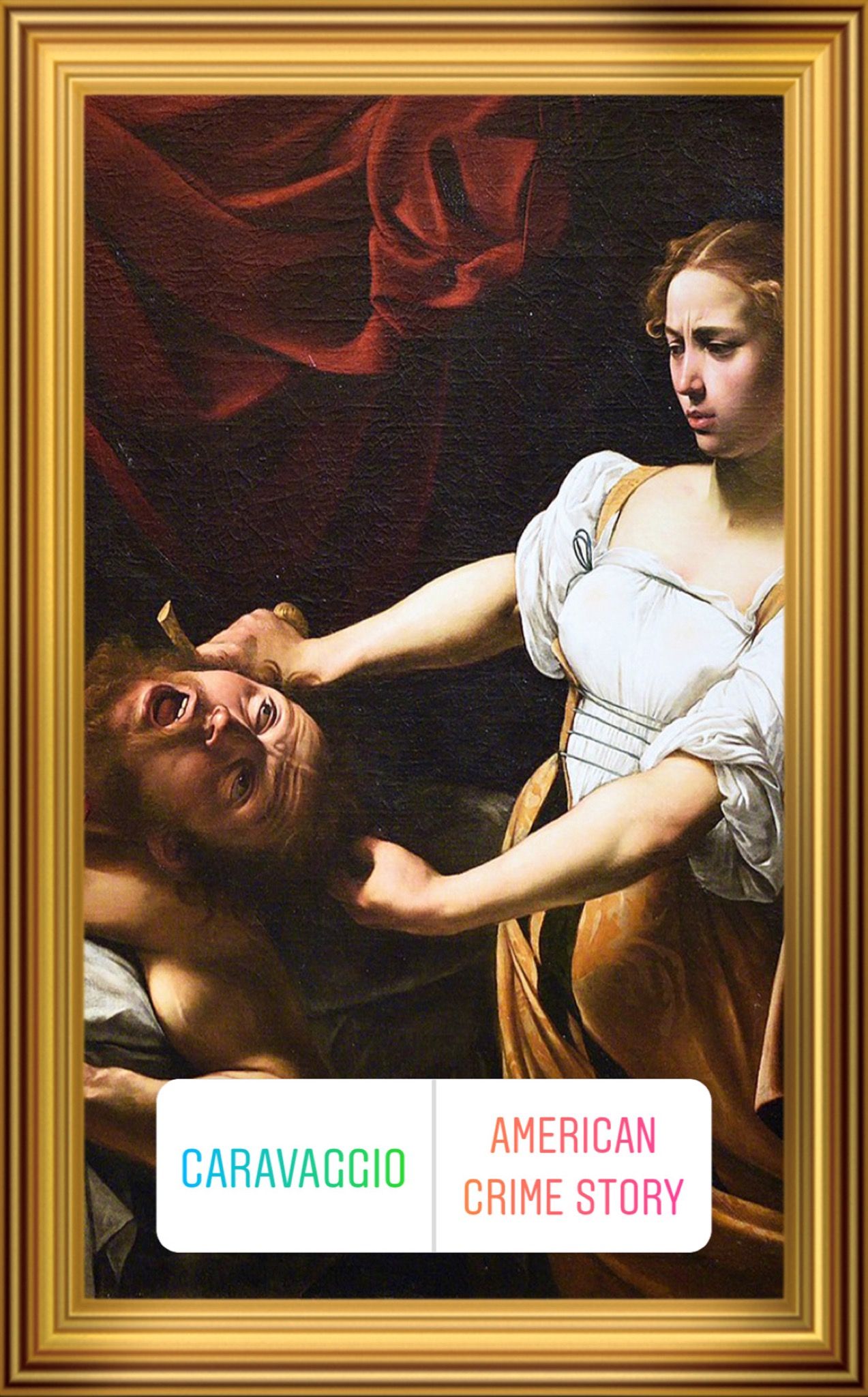

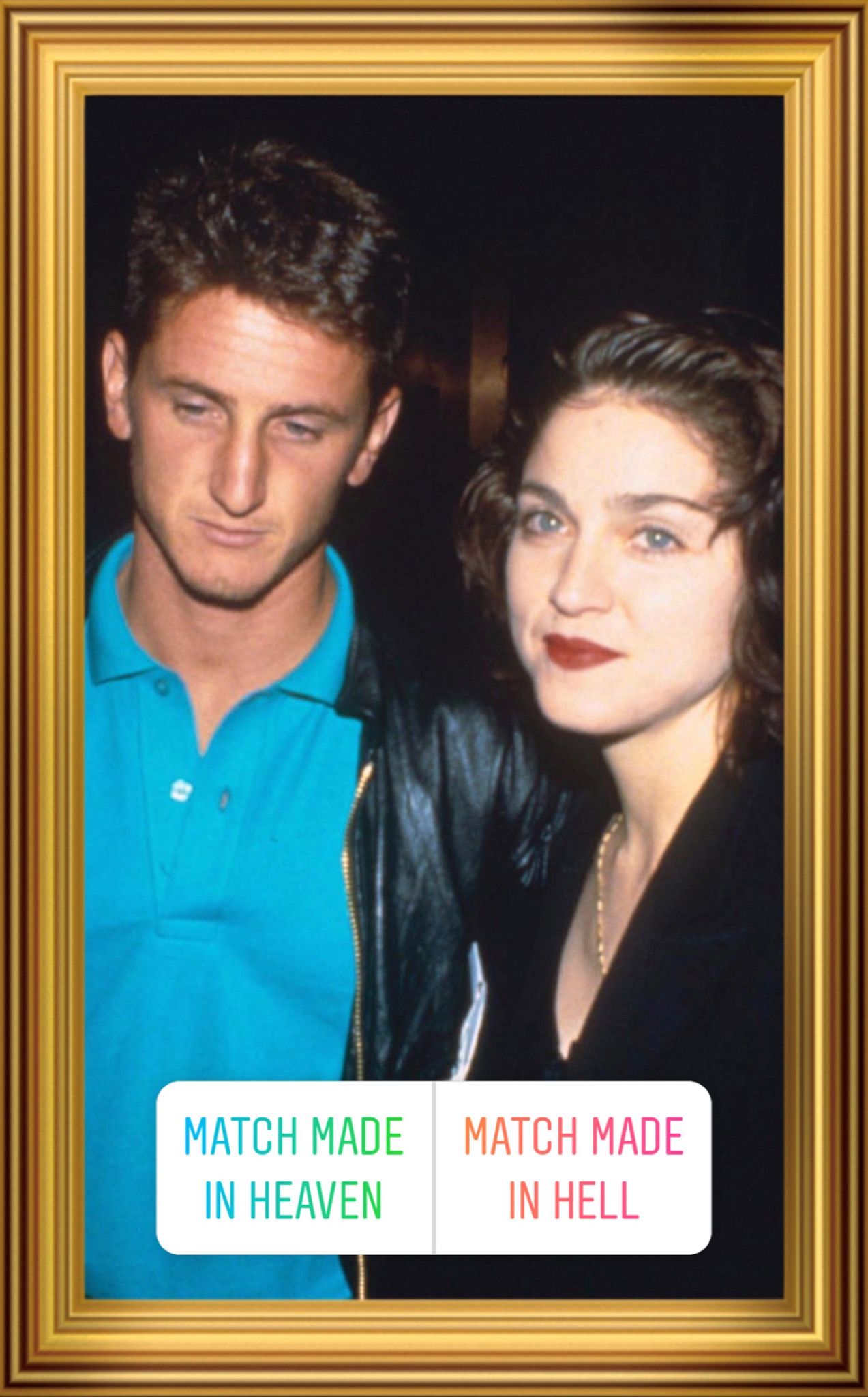

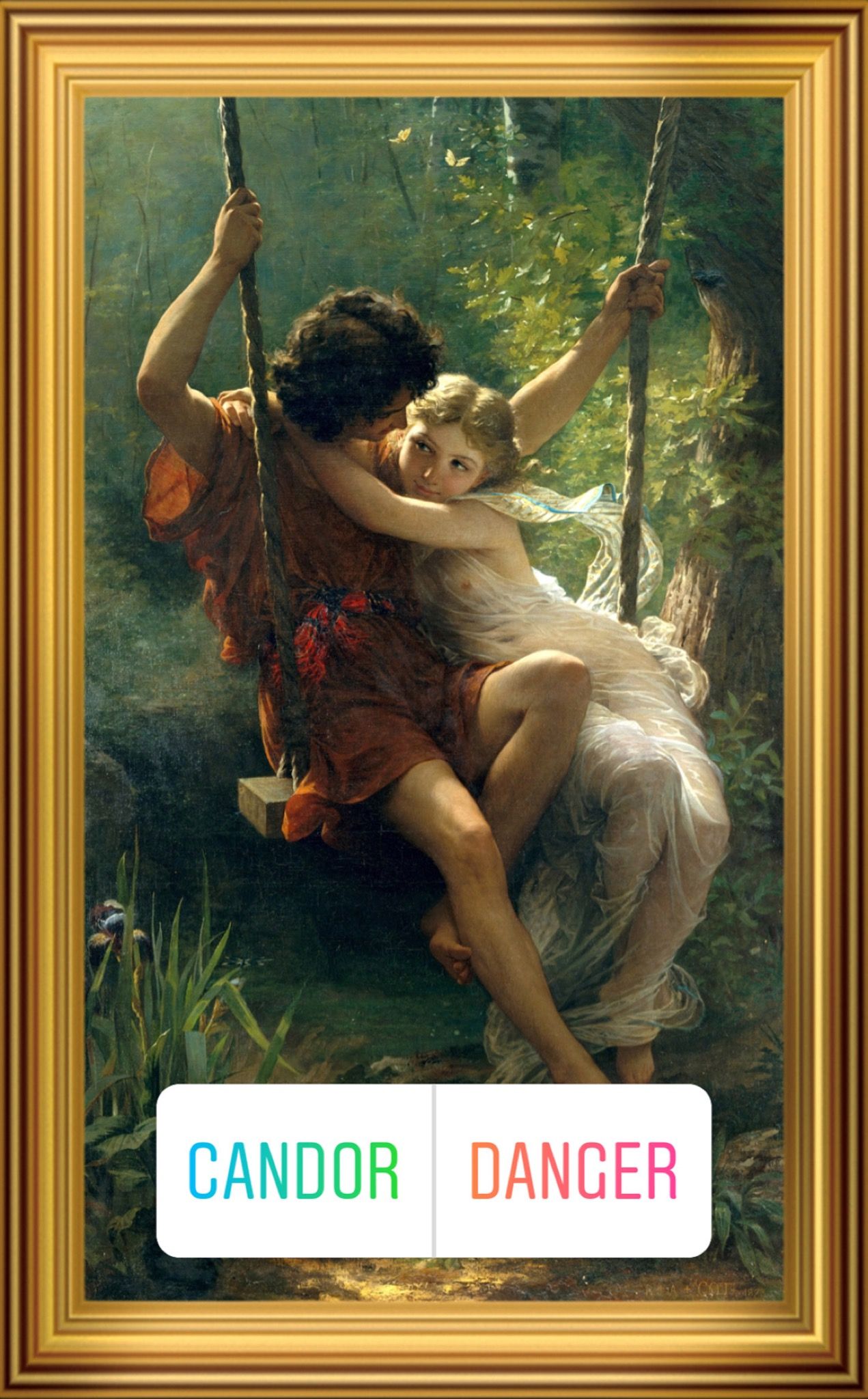

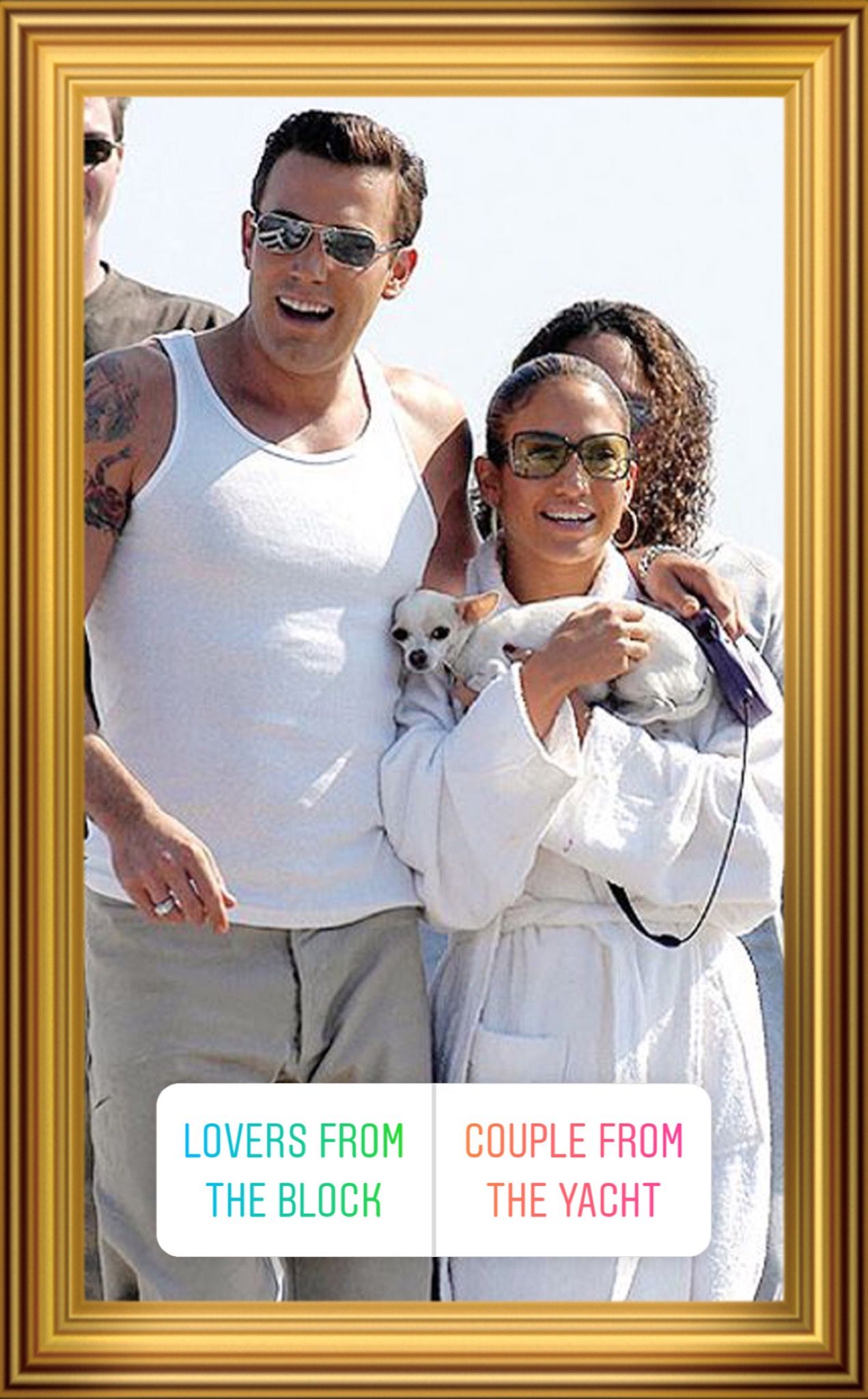

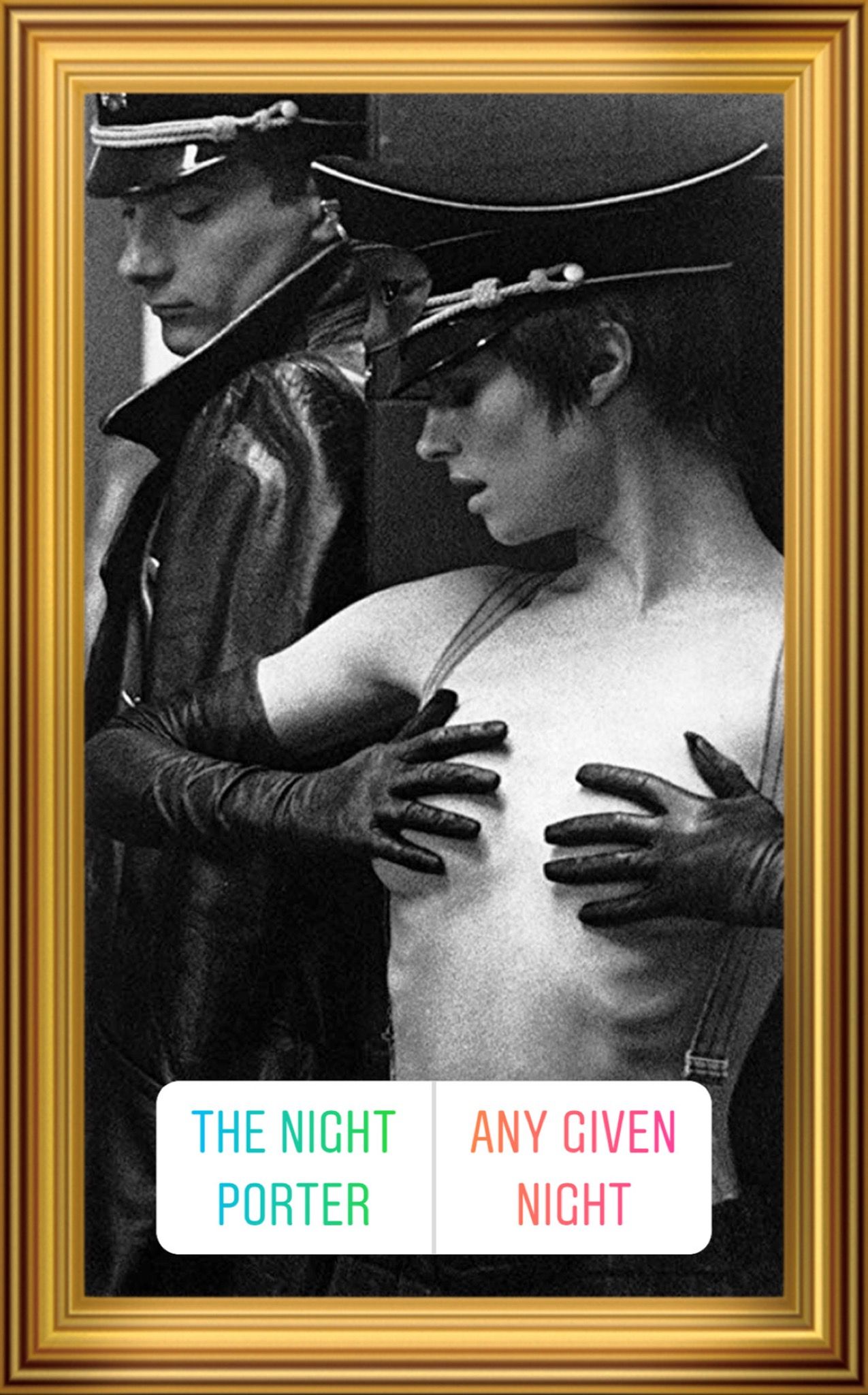

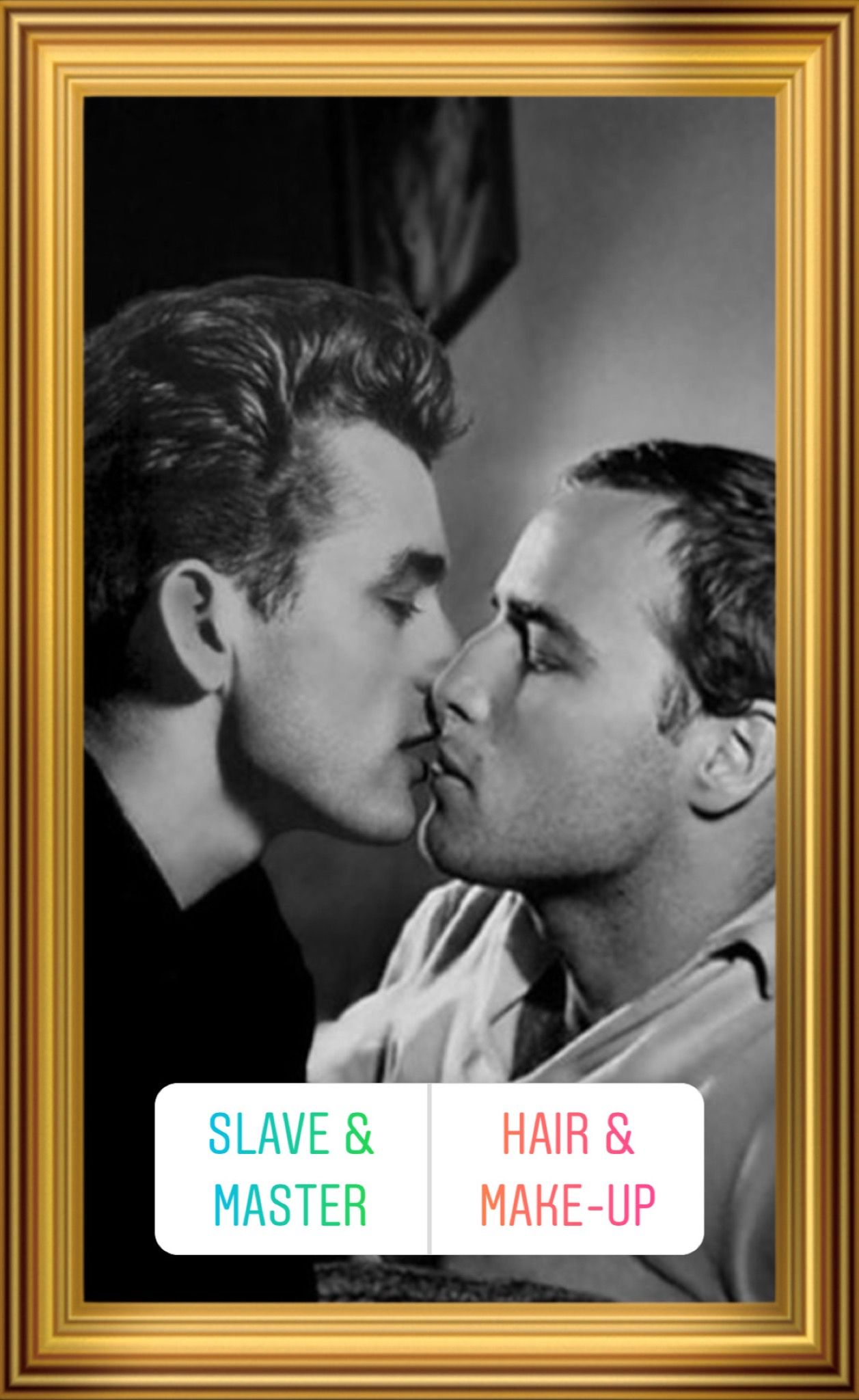

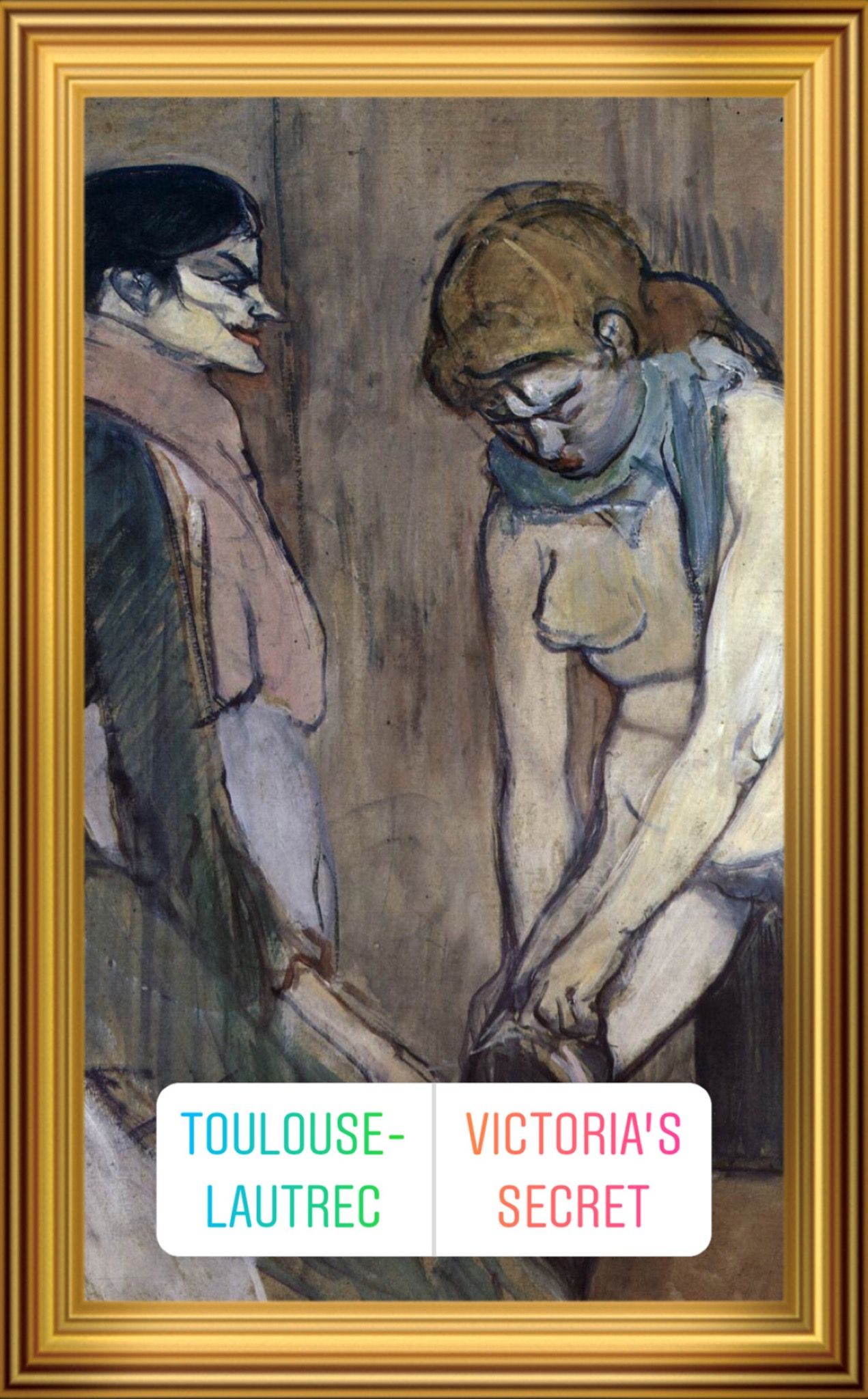

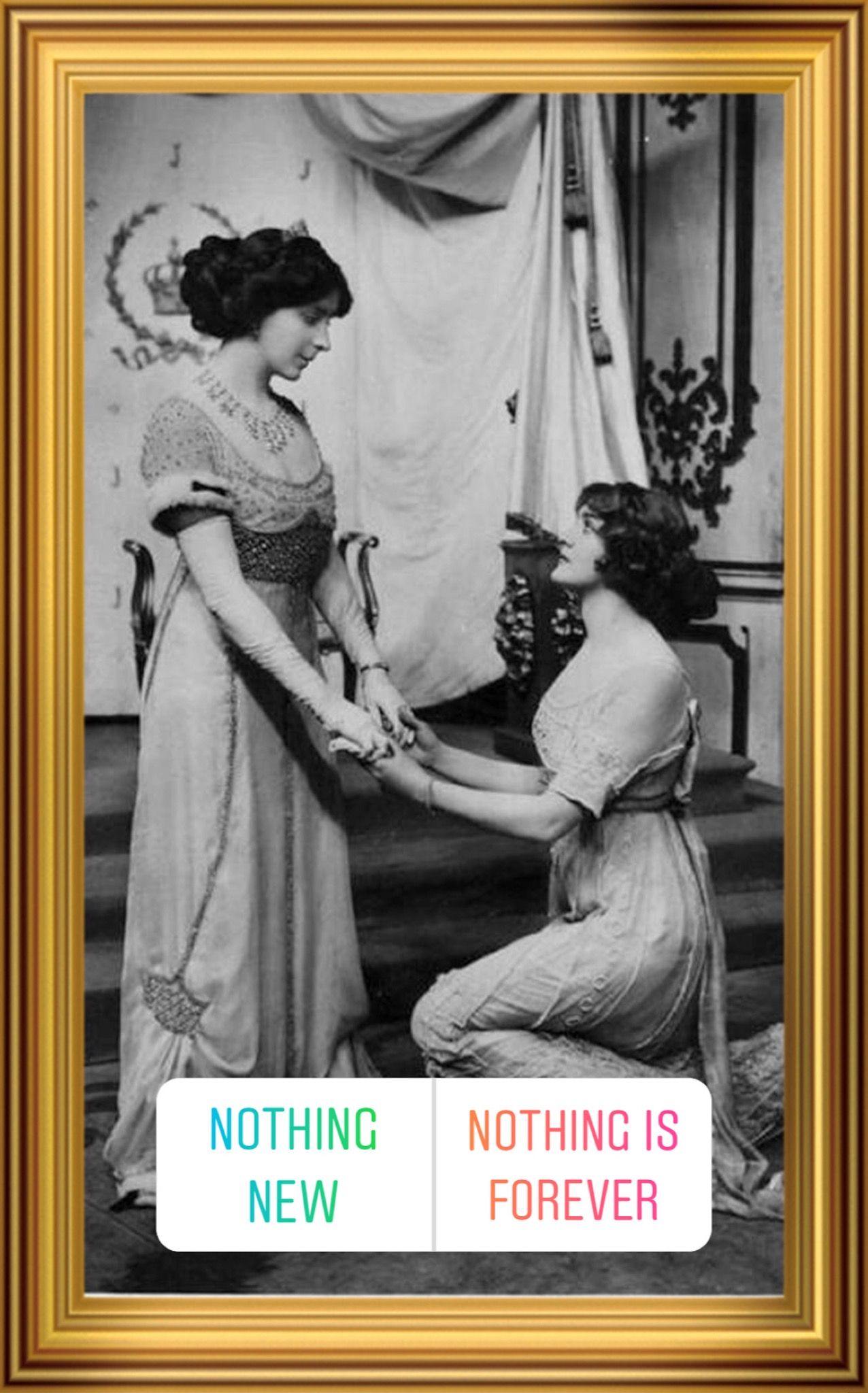

Vezzoli, horrified by the Covid-era Instagram landscape, and perhaps by the state of human intimacy in general, saw an opportunity to reclaim this space for community engagement. Launched last week and curated by Eva Fabbris, the Brescia-born, Milan-based artist’s latest commission for the Fondazione Prada, Love Stories, taps the platform as a barometer for the emotional state of users, tracking their sentimental vocabulary to create a portrait of the collective romantic psyche in an age of distance. Taking over the foundation’s Instagram “stories,” Vezzoli has created a serial poll that asks followers to respond to art historical and pop cultural depictions of love – or perhaps more broadly, of interpersonal relationships – by choosing between two divergent statements. Sometimes a celebrity couple, sometimes an Italian renaissance portrait, each image is accompanied by an operatic aria – either by an Italian composer or, in the case of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, about an Italian lothario – used as a means of conveying the drama, pathos, and hyperbole of cultural production having to do with love. The binary exercise of the poll sounds easier than it is: sometimes, neither “Caravaggio” nor “American Horror Story” will do as a response – although when I spoke to Vezzoli in the last days of April, we were both in “horror story” mode, neither of us remotely prepared for the loosened lockdowns and “new normal” so many cities were keenly charging toward. A week into the poll, the Love Stories plot thickened further: on May 17, Vezzoli appeared in conversation with MoMA chief curator at large and MOCA director Klaus Biesenbach, the first of many invited “experts” who will join the artist on Sundays to provide commentary on the previous week’s daily poll results.

Victoria Camblin: I see you have a beard. Is it a quarantine beard?

Francesco Vezzoli: Yes. It is a quarantine beard.

This is obviously going to be about Love Stories, but I think it is important to address the pandemic because you – and the Fondazione – are in Milan, at the heart of the European crisis, and because this project is taking place on social media, which is the main public forum we have access to as a result of the lockdowns. How are you?

How can I put it? Obviously I’ve been locked-in, and it’s not even that. Just to keep me company, I’m watching reruns of Downton Abbey, and the comparison with the war is superficial, everybody makes it and everything, but God! It’s shocking. For places like Brescia, my hometown, an entire generation of 80-somethings has been wiped away. That entire memory is gone. And of course no one really under 70 has ever seen anything like that. I mean, we hope to solve it from the medical point of view, with the vaccine and medicine. But it’s a wound.

You live by yourself?

Yes. I’m alone. I just moved into the apartment – and I’m not complaining; it’s a perfectly wonderful, beautiful place – but I have not left. And I think to be completely honest, I have developed a slight agoraphobia. Nothing dramatic, but when you are closed in a place for 60 days, you lose the contact with the outside.

I have noticed that you’re not really on social media.

No, I’m not. I’d been an Instagram spy for a while and then I gave up during the pandemic. Italy has been hit in a very serious and dramatic way, and I personally felt that, especially on Instagram, there were a lot of people that were showing insensitivity. People were posting images of the beach and saying, “I miss Ipanema.” I don’t give a fuck. On a day that 2000 people died, they could have spared us. It’s shocking. And these are the same people that three months before were all broken hearts for three bricks that fell off the Notre Dame. Then people die in your country and you post your ass on a Brazilian beach. I wouldn’t normally speak so ironically about the Notre Dame, but nobody died. France has so many great architects – Jean Nouvel could rebuild what’s missing and it would be amazing. I would run back to Paris for the first time in a long while just to see it after the pandemic. But they’re all praying hands and broken hearts for Notre Dame and during the pandemic they say, “Oh, I miss my holidays.” I’m sorry, you have to set your priorities right here, because otherwise you just make me vomit.

Do you even miss anything? I don’t. Maybe I will enjoy a restaurant again one day, but at this point I can’t imagine ever wanting to go out again.

So we feel the same. I don’t have the heart to miss anything. I am sad for the people who died. I am sad for the doctors who died. I’m sad for the people that go to work in the morning and are afraid that they’re going to be infected and die. You can put this [in] black and white. How can I say to you, “I miss Nobu?” I don’t have the energy to miss Nobu. And even if I miss Nobu, I can have Nobu delivered. I’ve seen the Pope all alone in that square. I’m not Catholic and I don’t have the gift of faith, but I’ve seen that man walk in the streets of Rome to go and pray to the crucifix of the God that supposedly sent the pandemic way back in the 16th century. I could stay home happily three months more if the television was giving me news that the results are improving. That fewer people are dying. If they said, “You stay locked in your house six months, and we’ll have a vaccine,” I’d say, “Okay. Easy. No problem.” Who am I to say I’m missing something? I’d sacrifice everything. And I praise the people who bring to my home the things that I desire when I need them.

Which brings us back to apps, in a way. You’ve worked with social media platforms in the past. For the 24 Hour Museum, a collaboration with the Fondazione Prada and AMO in 2012, you used a downloadable app to allow users to create Facebook portraits that were framed, project-branded, and modified to look like one of the Hollywood stars from The Museum of Crying Women. That was very early on in the face filter game, if not entirely ahead of it. You’ve also talked about Grindr as a way of charting the movement of bodies, which is of course an obsolete function now. How has your approach to social media evolved given the much evolved landscape?

Social media have totally changed because of the moment we are inhabiting. I would say that social media, especially Instagram, have become parallel industries, and there is not much you can do about it. I’m not Lady Violet from Downton Abbey – I accept the changes. For me, it’s Uber or Grindr or Tinder – the ones that end with an “R.” They are the ones that deliver you a service in times of peace. Those are the useful ones. Instagram is already too abstract. I’m not sure what service it provides, so I feel entitled to switch it off. Of course, I’m trying to say this with a joke – I mean, I’m not one of those enemies of social media. What we are doing with the Fondazione Prada has to do with social media, of course. Everybody’s discussing social media “before” or “after” the pandemic. But with what we did it was also important to say that if an institution wants to confront itself, if we’re doing a work that involves social media, it has to be a work that involves other people who cannot physically go to a museum. It cannot just be that you’re showing to me a film of your beautiful Donald Judd exhibition. I don’t give a fuck. I’m saying those words 300 million times in my life. And if you rearrange the art in a different way, well, I’d be more interested in a flower composition, okay?

“They’re all praying hands and broken hearts for Notre Dame and during the pandemic they say, ‘Oh, I miss my holidays.’ I’m sorry, you have to set your priorities right here, because otherwise you just make me vomit.”

Everyone is making memes about how all the “virtual exhibitions” are just slide shows or whatever.

I can’t stand them. They are just saying, “Oh, I’ll show you something new. I’ll show you my butterfly collection, but I just post them on Instagram, and then you come to bed with me.” Butterflies don’t do it for me. So this project was an attempt – as I always like to do, like the 24 hour museum – at experimentation. I was educated in a moment in history, where I was taught art had to be a certain way. We all remember Niki de Saint Phalle for her fatsy sculptures, but we forget when she did a [monumental sculpture of a] woman and you could enter through her vagina at the Moderna Museet. When we are left with objects from history of art, we tend to forget all the experiments that went on behind those objects. So I like to experiment. I’d had this project boiling up for a while: I had always wanted to make a big poll. To do that you can either hire a big poll structure and pay them a lot of money and whatever – or you do it on social media. When all of a sudden the Fondazione Prada was closed, for the reasons we know about, it seemed a perfect fit to try and think of a project that could engage an objectively world-renowned institution and try to make an artistic project that would really employ the involvement of the spectator. Not just create a digital viewing room. If I hear again “digital viewing room” I may finally get out of the apartment and go right and strangle whoever posted this digital viewing room. I don’t give a fuck.

It’s interesting that this project predates the lockdown. So you were already thinking about the poll format and the type of audience engagement that allows before it was really the only way to engage a large group.

Yes, I was thinking about it. And then about making it focus on love stories, and then creating a narrative of a couple and giving the audience two options to interpret it. You have two human beings, and two stories merging together as the story of the couple – plus two alternative perspectives on the identity of the couple. You have contemporary couples and you have a history of art angle. We have tried to spread our wings as wide as possible.

There is also an operatic motif, right? Can you tell us a little bit about that framework?

It’s very simple. It’s what I call the Bocelli theorem. Andrea Bocelli sang alone in front of the Duomo in Milan for Easter this year. I thought that was an incredibly powerful image. And then he sang for [the One World charity concert set up by] Lady Gaga. I know that many people, especially people in the snobbish art world, don’t like Bocelli. And I can see why. But it’s really about accepting that there are some threads that run through the culture of my country, and when the chips are down you have to go to the source, to what you’re good at. In this moment in history and with a project like this, we needed a universal grid, a universal framework. And we thought opera was really the place where feelings are discussed and described and narrated in the most direct, violent, explicit way. So looking for a soundtrack, we thought opera was perfect. It’s also an attempt to function by the schemes of the digital media: we need a frame for the image, and we need a soundtrack for the image. You have 15 seconds to create the Fondazione Prada moment. Then when it pops up – between an Ipanema bikini and an over-decorated cake made by people that have either nostalgia for holidays or are just trying to teach us how to bake another useless dessert – people are attracted, drawn into this slightly surreal poll about feelings.

And opera is also the original “total medium” right? An antithesis to Instagram, which is currently either people bitching about not being able to go somewhere or documenting their activities at home – not a particularly immersive environment at the moment.

Yes. Opera is the original, let me say to a German magazine, Gesamtkunstwerk.

Are you getting into any new apps or programs as well? Like TikTok has suddenly expanded its demographic, everyone is playing Animal Crossing, people are making their own Comme des Garçons style fashions on it. Maybe these world-building video games are closer to “total media” than apps like Instagram.

I’m not in the mood for TikTok yet. When they find the vaccine, I’ll be ready to go on TikTok. And I’d rather go on a website and try and buy some vintage Comme des Garçons. That would be my video game.

“If an institution wants to confront itself, if we’re doing a work that involves social media, it has to be a work that involves other people who cannot physically go to a museum. It cannot just be that you’re showing to me a film of your beautiful Donald Judd exhibition. I don’t give a fuck.”

Going back to the “real” world, is the idea that this project have some material form or physical engagement at some point, like the 24h Museum which also had events in a physical space?

I think that would be totally out of place. I think we have to stick to the fact that it was one of the first attempts to have a prominent institution make a serious project with an objective interaction with the audience, where the artwork is the question, the artwork is the answer, and the artwork is the comment on the answer. We are also gathering a group of prominent philosophers, talk show hosts, whatever, to make comments about these results.

Are the experts you are tapping for the project also coming from an Italian tradition?

No, we’re trying to put together like a fantasy football team that could win the champions league. Not to play the “good artist” who makes a speech about shared credit, blah, blah –if you know a little about my work, you know how many times I’ve worked with people, how many times I’ve discussed this notion of the absence of the author-reality, at least when it comes to my profession. So for me, in my case, this is an art call from the Fondazione Prada, which provides a platform that has numbers and visibility. I simply provide the bunch of cards. How do you say that?

The deck of cards.

The deck – I provide the decorated deck. Like the Cartier deck. Which was a typical corporate Christmas gift of the 1980s, 1990s.

Like the Hermes Ashtray or something?

Totally, you nailed it. By tonight you’ll be on a website buying a vintage one.

I plan to look that up after the call.

So I provide the deck of cards, and the audience will provide the answers, and then some great figures will provide an interpretation of the results, which may be completely on point. What the responses represent may be a complete misreading, because people have no confidence with the media. The only final output that I can see on top of this could be a book, with the options and the image reproduced with the results. Exactly like you have on Instagram, where when you click to respond you immediately see the number of votes. And then maybe even to report some of the comments that followers have posted, because that will give the flavor of how people are reacting. I think this is really the core of the project – always, and in a moment like this more than ever. It should be a project that involves people, and their reactions are as valuable as the deck of cards the artist provides. And together, they create an artwork. When the time will come – and fingers crossed – it could be the ultimate coffee table book.

Something to have out for when people are having people over to their homes again.

And they can play the game again they go, “Oh, people voted like this. What did you vote? Oh I would have voted something else.”

Maybe it could be an actual card game. Something you can play by yourself ideally. Like a Solitaire.

The Fondazione Prada card deck!

I’d buy that. Actually, have you been shopping online a lot lately?

It’s not politically correct to say it, but yes, because you’re alone. You’re at home, what do you do?

The first month I had just zero impulse to shop. I was only paying bills. But then about 5 weeks in suddenly I found myself browsing an online sample sale, and that was very dangerous. Very competitive.

Like those video games.

What do you think will happen to apps like Grindr, which are explicitly about brokering meetings where contagion risks are high?

Grindr, I don’t know. I mean, I can only answer this unless people find the vaccine or a medicine. What can I tell you – people are going to deal with this.

Speaking of apps built for sex, for intimacy, what do you make of the comparison between the current crisis and the early years of the AIDS crisis, where a community was trying to mitigate risk while still forming connections?

I have thought a lot about it myself. As a gay man coming to London to discover his sexuality, had to restructure my desire in order to live with that, in order to make my sexuality function, despite the AIDS epidemic. And then recently, around the days that the pandemic was exploding, it was in the news that a man in London finally had his blood cleared from any trace of HIV virus after 20 years on retroviral medicines. It was the strangest thing to read in those early days of corona.

What does seem similar is how much misinformation there was then and how little we know now.

Yeah. But here it’s something different. If it stays the way it is now in Italy for instance, where we only hear about how in order to preserve the health and economy of the country, we have a future ahead of us made of distances. So it’s a totally different set of complexities. Anyone who creates false promises or simplifies the problem – they’re doing a lot of harm. We will need smart countries to create smart counseling offices on how to approach this on a psychological level – but I don’t want to that to be set up by President Trump or Boris Johnson. Again, this all depends on how the medical discoveries will go. I hope my words will be outdated tomorrow morning.

That’s been the experience, right? We are all constantly revising our opinions, and what we know and think is changing on an hourly basis. And amid the uncertainty we are going to have to find ways to mitigate risk while still somehow connecting with other humans.

Oh yes. This is a project is about love stories. And love, and love stories, make the world go around.

Credits

- Interview: Victoria Camblin